By 2000 B.C. Crete, and its out post the island of Santorin, was the home of a remarkable, flourishing civilization. Known as Minoan, after the legendary King Minos, this civilization ranks with Mesopotamia and Egypt as one of the great centres of human development and progress. The Cretans were great seafarers and traders, they soon carried their civilization to other islands of the Aegean and to the Greek mainland. Archaeology has shown us that round about 1700 palaces in Knossos and Phaistos, the two chief towns of Crete, were destroyed by fire. They were rebuilt, however, and a bright new chapter seemed to open up for Crete. Then suddenly an even greater disaster overtook Cretan civilization, on a scale unknown since. The whole of Santorin exploded, with devastating effects for the surrounding area. From that day Crete never recovered.

The legend of Atlantis a tale, first told by Plato, of a great centre of civilization suddenly and violently destroyed by the sea has inspired generations of scholars to speculate on the possible historical reality of a lost continent. Some have subscribed to the theory that Atlantis may have been the Aegean island of Santorin, a flourishing outpost of Europe’s earliest civilization, the one that took root in Crete during the third millennium B.C. For early in the fifteenth century B.C., Santorin and Crete were hit by a series of natural disasters on a scale that has never been repeated in the civilized world. Archaeological exploration will no doubt continue to reveal more about this cataclysmic series of events; meanwhile, we know enough to show how remarkable was the civilization these islanders had created.

The first inhabitants of Crete are believed to have reached its shores some eight thousand years ago. These earliest settlers were peasant farmers, who arrived in ships, bringing with them some of their animals and their seed-corn. Their tools were of stone and they had not yet learned to work metal. Most likely they came to Crete from the east, either from the neighbouring coasts of Anatolia or from farther afield in Cilicia or Syria.

The settlers continued to have some contact with the outside world. For making sharp-edged knife blades they used obsidian, a volcanic glass that they could have obtained from Melos in the Cyclades Islands, some ninety miles north of Crete. Some of their obsidian, however, seems to have been brought from the distant region of Kayseri in central Anatolia. In the course of time stone vases from Egypt and copper tools from other areas also began to reach Crete.

At the beginning of the third millennium B.C. new groups of immigrants from the east appear to have settled on the island. These may have been refugees escaping from the great political disturbances of the time. For it was about then that the Nile valley was united by conquest under the rule of one king, Hor-Aha, to inaugurate the First Dynasty of Egypt. One of the earliest kings of Egypt’s new dynasty extended his conquests into southern Palestine and styles of pottery appearing in Crete suggest that refugees may have come to the island from that area.

Along with new styles of pottery, the art of metallurgy — making tools and weapons of copper and eventually of tin-bronze — seems to have been introduced to Crete at this time. In the centuries that followed, while the great pyramids were being erected in Egypt, other groups of immigrants found their way to Crete from the east. Some may have been fleeing the barbarous invaders who overran Syria and Palestine about the middle of the third millennium.

Brought to Crete by refugees, or by traders, ideas and arts such as those of stone vase-making, seal-engraving and writing, soon became established on the island. By the end of the third millennium the island had become the seat of a high civilization, the first on European soil, with cities and large palaces apparently belonging to rulers who were able to concentrate power and wealth in their hands. .

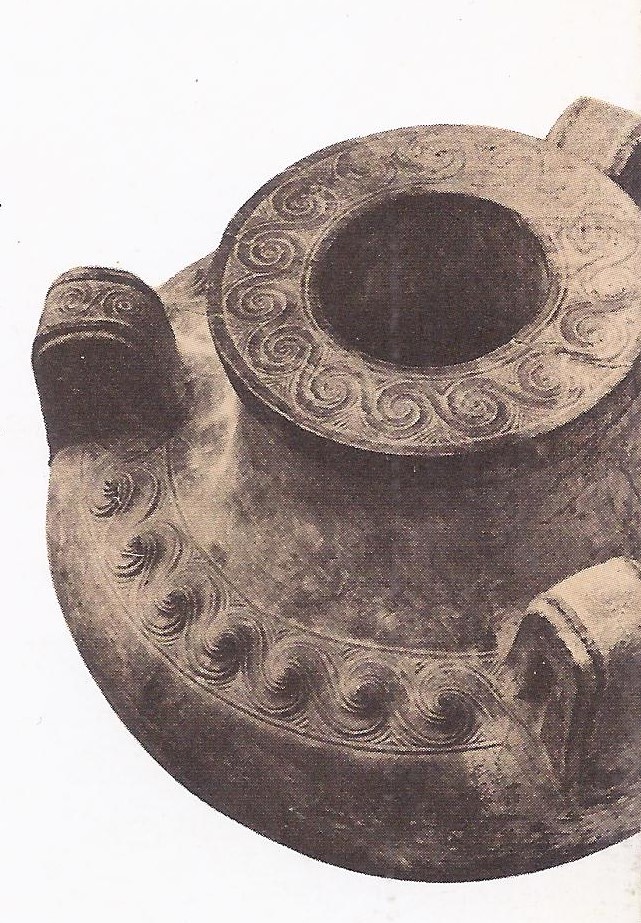

This new civilization, while deriving much from Egypt and even more perhaps from Syria and Mesopotamia, was something very different; and in turn it influenced the older cultures. The spiral designs that became fashionable in Egypt from about two thousand B.C. onwards, during the Middle Kingdom, may have been inspired by the spiral decoration on imported Cretan textiles. No such textiles have survived; but fine painted pottery from Crete, some of it with Spiral decoration, has been found in Egypt and many Egyptian objects — beads, scarabs, stone vases and ivories reached Crete.

A brilliant civilization in the Aegean

The Cretans were evidently seafarers and traders. Many of their most important towns were on the coast where sandy beaches allowed the small ships of those days to be hauled ashore. Pictures of these ships on seal stones show them with single mast and square sail supplemented by oars or paddles.

In about 1700 B. C. the two largest palaces in Crete, at Knossos in the north and at Phaistos near the south coast, were destroyed by fire — whether by accident or as a result of earthquake or war is uncertain. Crete at this time appears to have been divided into several independent states, which probably indulged in intermittent warfare among themselves. The destruction of the palaces may also have been caused by foreign enemies, but if so, there is no evidence that they remained on the island.

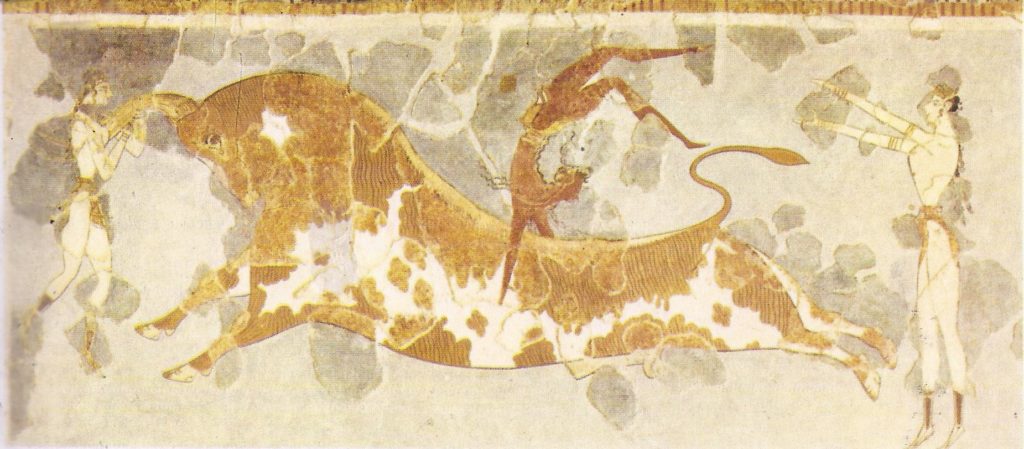

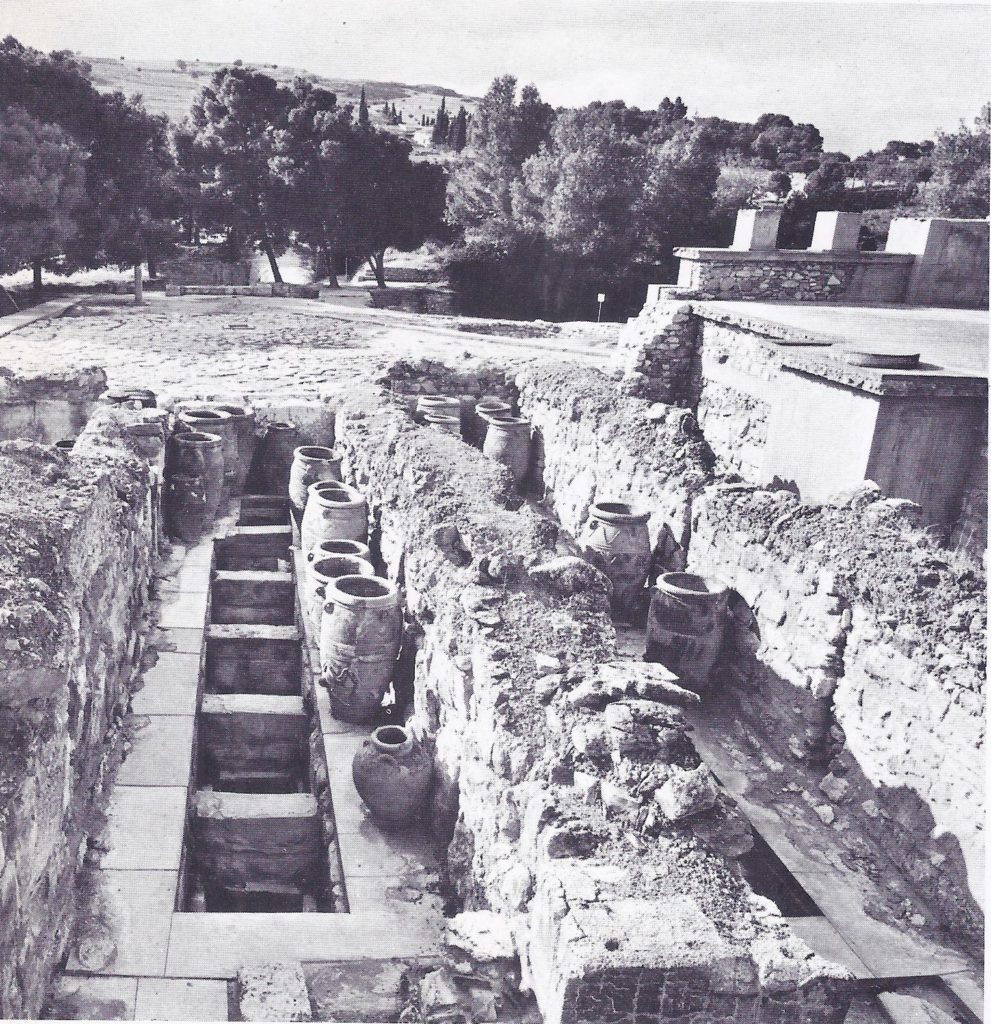

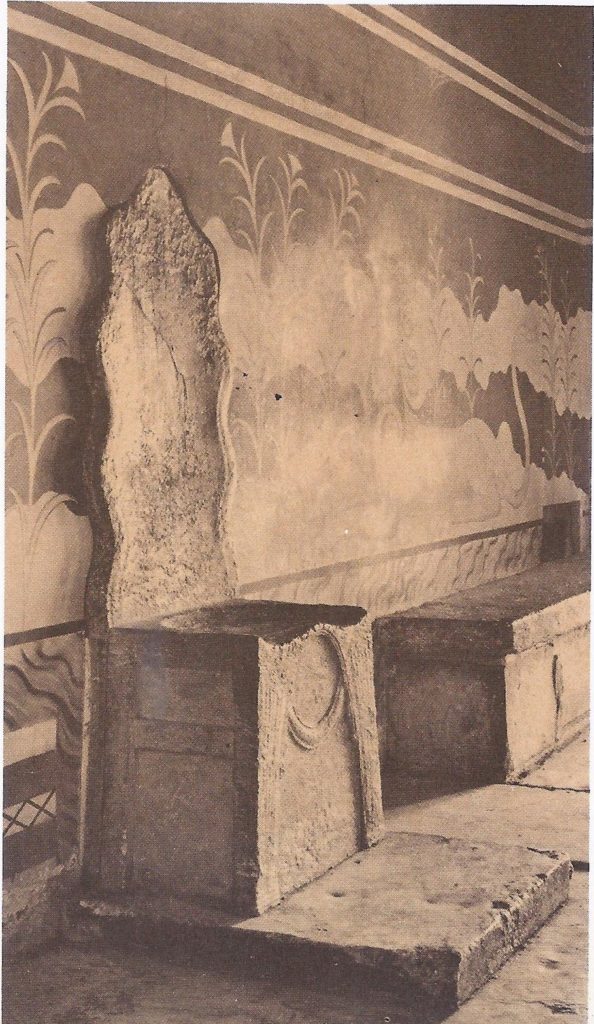

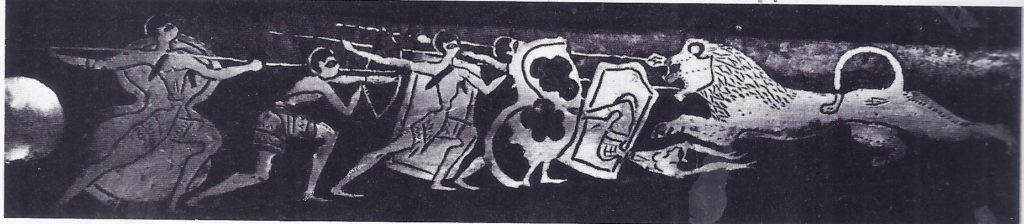

After this destruction, the palaces at Knossos and Phaistos were rebuilt with even greater magnificence and splendour to inaugurate what was to be the most flourishing period of the Bronze Age Civilization of Crete. Noble paintings in fresco now adorned the walls of the palaces and great houses. The arts of metal-working, gem-engraving, ivory-carving and faience-molding reached their highest perfection, although the art of pottery declined, probably because vases of metal — copper, gold and silver — were now in general use in the palaces and houses of the great.

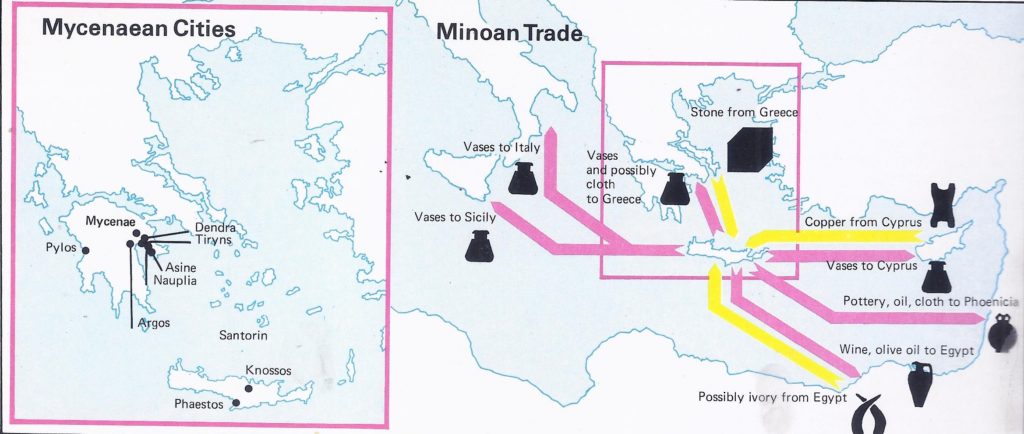

This vigorous and attractive civilization began to spread beyond the shores of Crete, it the northern islands of the Aegean and to large areas of the Greek mainland. Evidence of Cretan culture can be seen in the unplundered royal shaft graves at Mycenae, the chief city of the mainland. The earlier graves, which may date back to the seventeenth century B. C., contain some vases and other objects imported from Crete, while in the later graves, of the sixteenth and fifteenth centuries B.C., nearly all the vases, weapons and jewelry are of Cretan manufacture. Of course, it is hard to tell whether these were imports, or whether they are the work of Cretan artists employed at Mycenae or native artists trained in a Cretan style.

The spread of Cretan civilization to the mainland of Greece was perhaps largely the result of peaceful intercourse and admiring imitation, but there may have been a harsher side. In that imperialistic age it is only too likely that the rulers of Crete attempted to extort tribute from the princes of the mainland just as the contemporary pharaohs of Egypt did from the petty Chieftains of Syria and Palestine.

Later Greek legends hint that there was a time when parts of mainland Greece were tributary to the kings of Knossos in Crete. Some of the most intriguing of these legends concern Minos, king and legislator of Crete and the labyrinth at Knossos built to house his wife’s monstrous offspring, the Minotaur. It seems possible that the legends concerning Minos’ maritime conquests, even as far as Sicily, are based on considerable Cretan expansion in the Mediterranean and on kings who checked the piratical expeditions of their Aegean contemporaries.

Crete seems to have become heavily populated during this period from the seventeenth to the fifteenth centuries B.C. Everywhere throughout the island today there are traces of towns, villages and hamlets, even of isolated villas and farms, dating to those centuries. There may even have been a danger of overpopulation, the classic remedy for which, in later Greek times at least, was overseas colonization. Later Greek tradition recalls colonies of Cretans in the islands of the Cyclades and archaeologists have identified a number of these, probably founded in the course of the sixteenth century B.C.

Disaster strikes Santorin

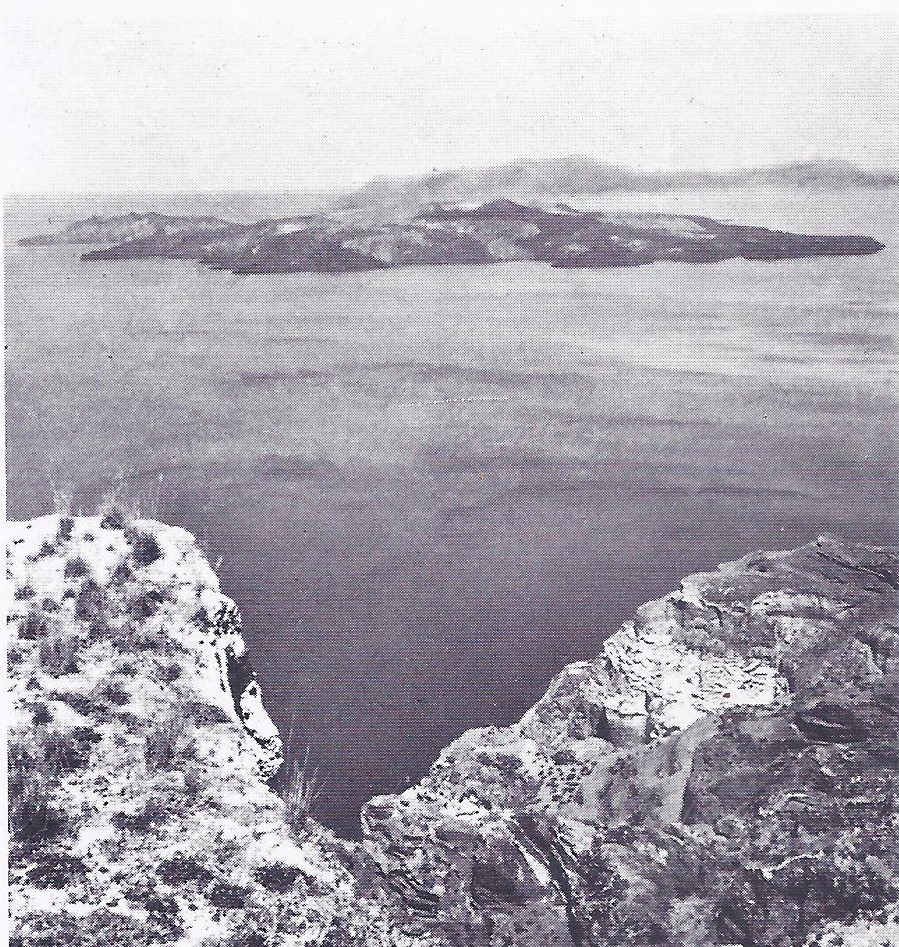

One of the islands settled by Cretan colonists was Santorin, the ancient Thera, seventy miles north of Crete and the nearest of the Cyclades to the “homeland.” Santorin is a volcano island; but at the time the Cretans settled there its volcano seems to have been long quiescent.

Crete and the Cyclades are much subjected to earthquakes and tectonic disturbances of every kind — several times in each century some part of the main island suffers in this way. About 1550 B.C. or a bit later, an earthquake of unusual severity struck Knossos and many of the towns and settlements in the east of Crete. The damage was soon repaired and the palace at Knossos and the houses there and elsewhere were restored.

Not long afterwards, however, early in the Fifteenth century B.C., Crete was ravaged by another major earthquake. The destruction caused by this can also be traced at Knossos and the settlements of eastern Crete. This second earthquake may have been connected with a catastrophe on Santorin. For the volcano there, so long inactive, erupted about this time and buried the island’s Cretan colonies. Most of the colonies however, seem to have had time to escape, taking with them their most precious belongings. Excavations have revealed the houses of the colonists wonderfully preserved — as at Pompeii — below the debris of the volcano. Yet only one or two skeletons of human victims have been found and there is little in the destroyed houses other than clay vases that were expendable.

Some time after this catastrophe — it may have been several years later a few of the colonies appear to have come back to Santorin. Traces of new houses have been found above the debris of the eruption.

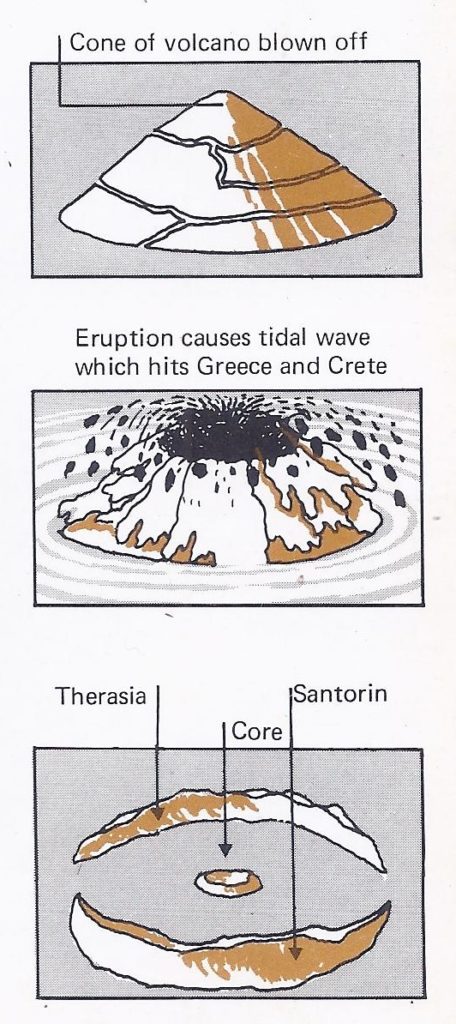

The third and final act in this drama of natural disasters was yet to come. The eruption of Santorin was merely the prelude to a cataclysm of a magnitude that has never been exceeded. A generation or so later, about the middle of the fifteenth century B.C., the whole island of Santorin exploded.

The only comparable natural disaster in history is the explosion in 1883 of the volcano island of Krakatoa in the Sunda Strait between Java and Sumatra, Indonesia. The sound of Krakatoa’s eruption was heard as far away as Australia, the Philippines and Japan. The debris of stones and ash shot to a height estimated as seventeen miles or more; on islands in the neighborhood of Krakatoa the deposit of debris was thick enough to cover entire tropical forests, while finer dust suspended in the atmosphere, eventually spread over the greater part of the surface of the globe. At Jakarta, a hundred miles away, day was turned into night, as debris darkened the sky for days. The aftermath of the explosion was even more destructive. The great hollow crater left by the escape of debris collapsed and most of Krakatoa disappeared into this void. Where a cone 1,400 feet above sea level had once risen was now a gulf more than one thousand feet deep. Into this gulf the sea poured, causing immense tidal waves, between fifty and one hundred feet high. The waves swept over towns and settlements along the adjacent coasts, killing more than thirty-six thousand people.

The explosion of Santorin about 1450 B.C. is judged to have been on a very much greater scale than that of Krakatoa. The north coast of Crete, only seventy miles away across the open sea, was thickly studded with populous towns and settlements; these coastal settlements and many of those in the more protected interior of the island, must have been wrecked by the blast of the explosion. Some time afterwards the vast empty crater left by the escape of the debris, collapsed. The island Santorin, which had been more or less circular in shape, rising to a high cone in the centre, became the jagged group of two islands that it is today. As in the case of Krakatoa, the sea swept into deep void, causing huge tidal waves, probably as much as a hundred and fifty feet high. When they bore down upon the north coast of Crete, such waves would have flattened all that the explosion had left standing. Meanwhile the debris from the eruption, hanging in the air, must have enveloped Crete in darkness for days on end and poisonous fumes and vapours would have added to the suffering and terror of the survivors.

Many of the Cretan settlements destroyed at this time have been excavated, but at only one of them, Amnisos on the coast north of Knossos, has evidence of the tidal waves being noted, in the form of a layer of pumice stones over the ruins. Debris from the explosion has been identified in the wreckage of a palace at Zakro on the east coast. The Zakro palace and many of the buildings destroyed at this time elsewhere in Crete, had also been ravaged by fire. Moreover, although many fine vases of clay, stone and faience, bronze tools and inscribed clay tablets were recovered at Zakro, there was virtually no trace there of precious metals and none whatsoever of victims of the disaster. Here and elsewhere in Crete it looks as if people had some warning of catastrophe and time enough to escape into the open with their most valued possessions and household effects.

It has been suggested that the explosion of Santorin was triggered by an earthquake with its centre in the seabed of the north coast of Crete. Earthquakes often begin with warning shocks and result in fires spreading from hearths or lamps in houses. The initial destruction of the palace at Zakro and of the other towns and settlements in Crete, may have been due to an earthquake and the fires it caused — followed by the explosion of Santorin and by the resulting tidal waves.

The end of the Santorin Empire

The material damage produced by this series of disasters was clearly immense. Most of the chief centres in the populous north and east of Crete had been totally destroyed and those elsewhere had been wrecked. The eastern end of Crete seems to have been altogether uninhabited for a considerable period after the cataclysm, because of the direction of prevailing winds, the deposit of debris must have been thicker there than elsewhere in Crete and laden as it was with poisonous chloride, would have killed vegetation and made life impossible for man and beast.

The towns in the east of Crete were eventually resettled, but the palaces there were never rebuilt. After the cataclysm, Knossos seems to have become the capital of a centralized bureaucratic state controlling most if not all of Crete. This may have coincided with a change of dynasty at Knossos, perhaps with rulers who were strangers either from another part of Crete or from abroad. It is possible that conquerors from the Greek mainland took advantage of the chaos and confusion that overwhelmed Crete after the cataclysm to gain control of Knossos, but the mainland too must have been seriously affected by the disaster and the archaeological evidence for a subsequent conquest of Crete from abroad is ambiguous.

The palace of Knossos was destroyed yet again by fire, probably early in the fourteenth century B.C., but at this time it was not rebuilt. The inscribed clay tablets found in its ruins have been deciphered and tentatively identified as an early form of Greek. If the language of the tablets really is Greek, then it is highly probable that Greeks from the mainland won control of Knossos and ruled there after the Santorin catastrophe, but this decipherment is contested.

The explosion of Santorin may therefore have led to great political changes, but there is no certainty as to their character. The cataclysm happened to coincide with a marked decline in the quality of Cretan civilization. There is evidence of much wealth and splendour in Crete during the century or so between the cataclysm and the final destruction of the palace at Knossos, but a deterioration is noticeable in taste and workmanship — except that employed in making tools and weapons. The explosion of Santorin did not cause this decline, which seems to have begun much earlier. The decline was accelerated after the final destruction of the palace at Knossos, a destruction that seems to have been the work of enemies. Afterwards, Crete, plundered and impoverished, may have become part of an empire ruled from Mycenae on the Greek mainland.

Towards the end of the thirteenth century B.C. Mycenae and the other chief centres of the Greek mainland were in turn destroyed by people moving into Greece from the north. Refugees from the devastated areas made their way overseas and some of them came to Crete. After an interval, they were followed by other invaders, who occupied the fertile central parts of the island including the region around Knossos. Many of the previous inhabitants escaped abroad or took refuge in the mountains. Finally, at the very end of the Bronze Age, in the eleventh century B.C. the Dorian Greeks arrived to settle in Crete. With the coming of the Dorians the old Bronze Age civilization of Crete at last came to an end.

For three thousand years or until archaeologists began probing Crete’s ruins late in the nineteenth century — only such vague legends as that of the lost continent of Atlantis survived to remind man of Europe’s earliest civilization.