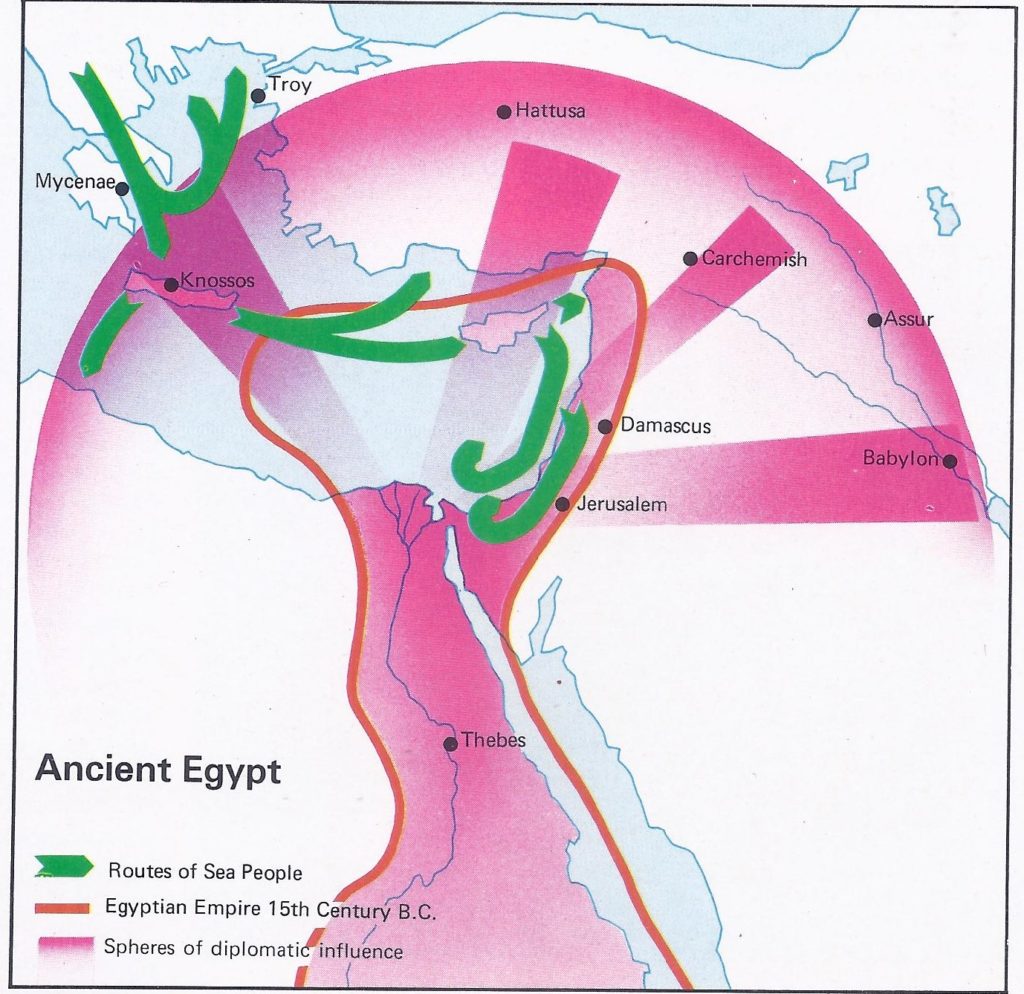

For several years the Sea Peoples from the north had been drawing closer and closer to Egypt. Syria and Libya fell to them and under the leadership of Mernera of Libya they began to prepare for an assault on Egypt itself. Merneptah, son of Ramses II, decided to take the initiative and attack first. His strategy was justfied by his resounding victory, but the Sea Peoples learned a lesson and devised a new tactic. They began to infiltrate the country in families and groups. Unknown to the Egyptian administration, a new onslaught of Sea Peoples was about to occur. Happily for Egypt there was a man equal to the situation in the person of Ramses III.

In the eighth year of his reign, in 1191 B.C., Ramses III mobilized the Egyptian armies, together with their mercenaries, auxiliaries and allies, to halt an invasion of the Sea Peoples. Egypt was facing some of the toughest enemies in its history. Who were these mysterious Sea Peoples, as they are referred to in the official documents that chronicled the numerous campaigns fought against them during the reigns of Ramses II and Merneptah?

The Sea Peoples were nations of very diverse origins, engaged in joint expeditions of conquest and plunder. They included the Aqaivasha, who were probably Achaeans; the Tursha or Tyrrhenians; the Shakalsha or Zekel, who came from Sicily; the Shirdana or Sherden, who originated in Sardis or possibly Sardinia; the Denyen or Danaeans, originating from Greece; the Peleset, referred to in the Bible as Philistines; and the Louka or Lycians. These men, although from different stock, had one thing in common: Indo-European racial characteristics, with features astonishing to the Egyptians. They were “all northern peoples,” declare the Victory inscriptions of Merneptah in his temple at Karnak, “coming from all sorts of countries and remarkable for their blonde hair and blue eyes.”

These people were nomads, or perhaps they had been forced into a nomadic way of life by the great migrations of about 2000 B.C., which had completely changed the Near East and the Middle East. The descent of the Indo-Europeans into Greece, Asia and to some extent India had been irresistible and devastating. The Peleset, for example, who originated in Crete, established themselves first in the region of Syria and then in Palestine, warring against the Hebrews; while other tribes invaded the banks of the Orontes and the kingdom of the Amorites.

The conquest of Kheta, which had tried to oppose the insidious infiltration and brutal aggression of the Sea Peoples and the defeat of the Hittites put Egypt in great danger; for the great Delta, networked by numerous tributaries from the Nile, offered easy entry to the warships of the Indo-Europeans who aimed to command the seas. Some of these people already had entered the service of the pharaohs, who admired their military valour and gladly employed them as mercenaries. Among these were the Shakalsha, the Shirdana and the Louka. Others, like the Aqaivasha (the Achaeans who are found in Greece at virtually the same period) were newcomers.

Seti I had already been alarmed by the establishment of these Sea Peoples in Syria and their obvious appetite for attacking neighbouring countries and their large-scale irruption into Libya, where the native tribes had been overwhelmed. One of the principal aims of Seti’s campaigns in Libya had been to neutralize their power. In this he succeeded and he gave Egypt a long period of peace from these particular enemies. It was not until the end of the reign of Ramses II, Seti I’s successor, that the threat from the Sea Peoples caused the pharaohs any great concern. Then came a considerable upheaval in Eastern Europe, principally in the Balkans and around the shores of the Black Sea and nomads moved in the direction of Asia Minor, Greece and the Aegean islands: and finally Libya — that is to say, they moved in closer to Egypt. Once again it became necessary to take the offensive and fortify the frontiers, or better still, to attack the nomads before they became invincible.

A reforming Pharaoh

Ramses II was eighty, too old, too tired and too disheartened to take the initiative. He handed the responsibility and the honour to his son Merneptah, who, in the fifth year of his reign (c. 1227 B.C.) attacked Libya. Merneptah justified this action in view of the preparations made by the Libyan king Merai, who was gathering the Sea Peoples together under his command. Tempted by the fertility of the Nile Valley, they were preparing to invade either by chariot along the land routes, or by sea.

The inscription called the “Stele of Israel,” discovered in Merneptah’s temple tomb in Thebes, records the events of the war and Merneptah’s success; the inscriptions on the walls of the temple tell us more. The engagement took place at Per-Ir in the Delta, to the north of Memphis. After a battle lasting six hours, the Sea Peoples retreated; 9000 prisoners were taken. In order to make his victory yet more effective, the Egyptian ruler pursued Merai’s troops as far as Palestine and ravaged their settlements in the lands of Canaan and Ashkelon. This punitive expedition did not spare the Hebrews: “Israel is laid waste and its people no longer exist,” the inscriptions record.

After this triumph, Merneptah had no more trouble with the Sea Peoples, nor did the five pharaohs who succeeded him, but Egypt was possibly enjoying a false sense of security. The Sea Peoples had learned prudence from their failure and never again risked a full-scale attack on their neighbour, but neither did they abandon the idea of infiltrating the Delta and taking possession of it.

It has been rightly said of Ramses III that he was “the last great king of the ancient empire.” From the moment he succeeded to power in 1198 B.C., he was conscious of the vital need for reforms in his kingdom, above all in the administration and the army. Under his predecessors, foreign policy in regard to Asia had been feeble and neglected. Libya had re-established its power and the Sea Peoples, in spite of their defeat at Per-Ir, were once again planning an attack on Egypt.

Their tactics, however, had changed. Unobserved by the frontier garrisons, they infiltrated the Delta in small groups of a few families each, then gradually moved south. Without the knowledge of the administration, they set up small collectives, apparently peaceful settlements but capable of becoming formidable instruments of war if their inhabitants banded together. The Egyptians over a long period had employed aliens, sometimes as soldiers and sometimes as workmen and this facilitated the integration of these foreign races, who little by little mixed with the native population despite racial differences.

In the melting pot of this Afro-Asian immigration were Bedouins, Syrians, Cretans, Lydians and Canaanites. They were a motley crowd, lacking in discipline and hostile to the edicts of the administration and to the laws of a country to which they owed neither physical nor moral allegiance. Such internal disorder and lack of civic sense among people who lived in Egypt as though they had conquered it, yet who refused all the obligations that conquest entails, endangered the security and prosperity of Egypt. This was at a time when Palestine, Syria, Naharin, Cilicia, Cyprus and the lands of the Amorites were in the hands of the Sea Peoples, before whose onslaughts even the powerful Hittite bastion had collapsed.

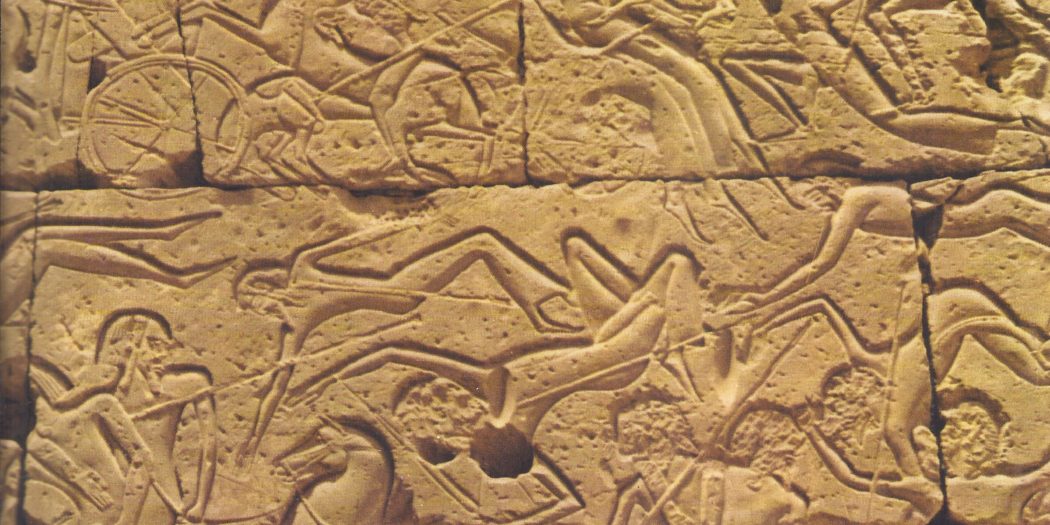

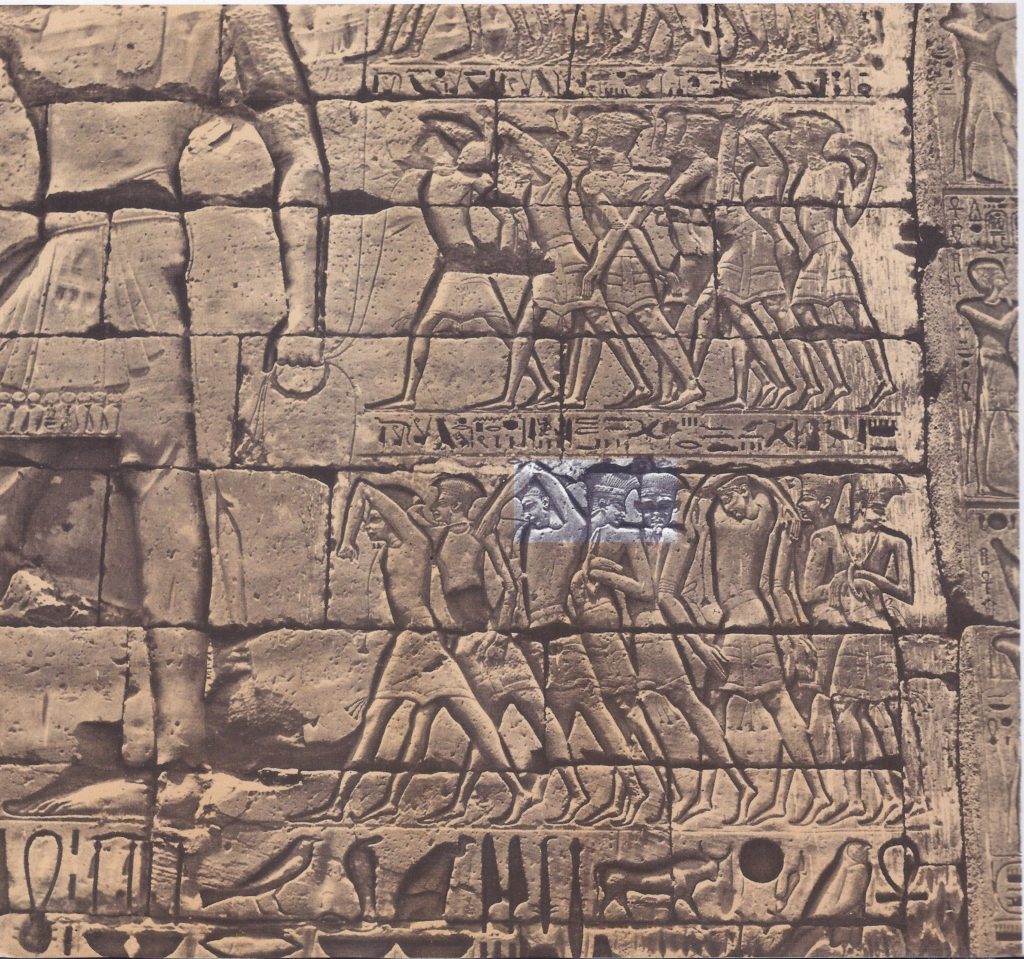

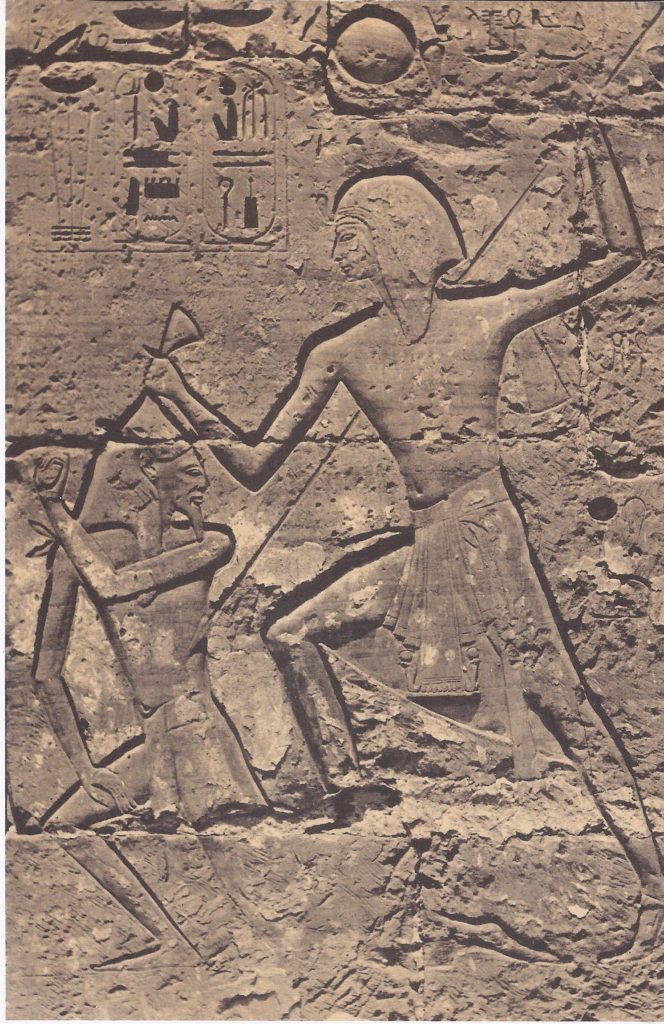

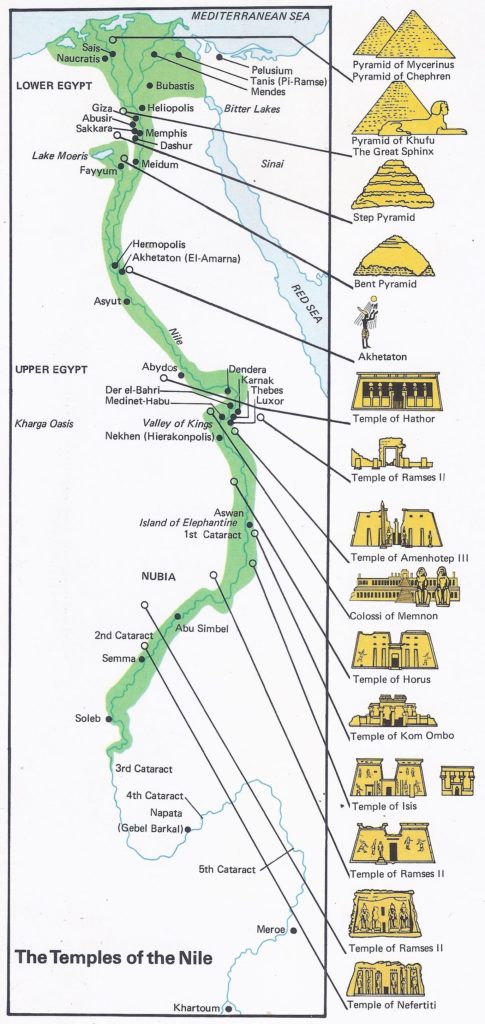

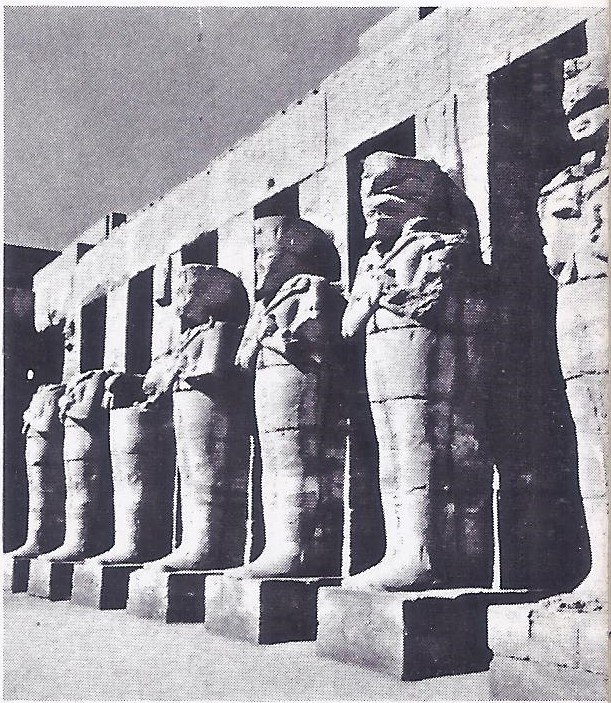

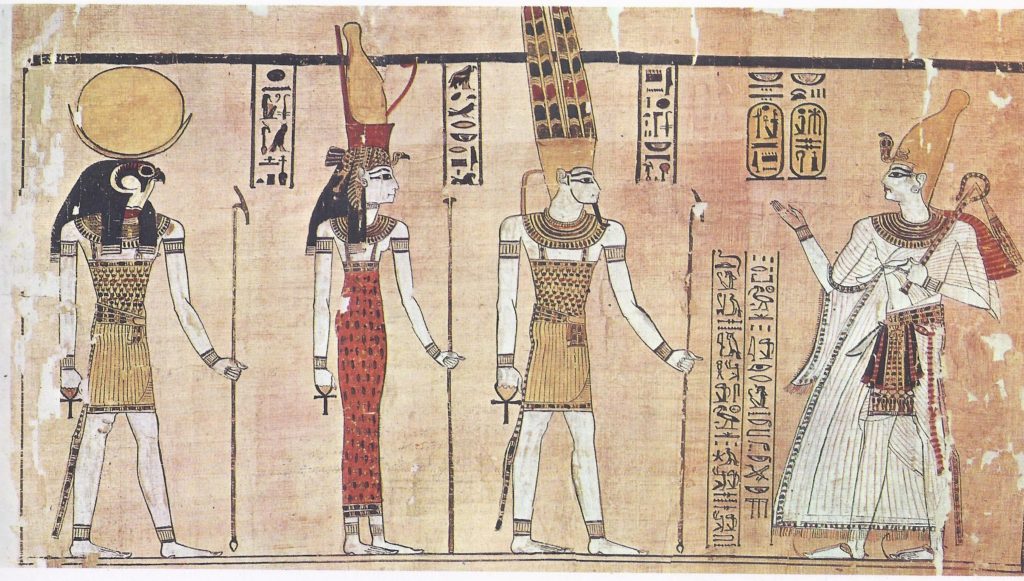

It was providential that at this time of great danger, a king who was wise, intelligent, energetic and bold succeeded to the throne. The bas-reliefs of the temple that Ramses built at Medinet-Habou record, in epic style and imposing pictures, the triumphs of the sovereign, the wheels of his war chariot grinding his enemies into dust. Along the north wall of the temple, a gateway almost 230 feet wide, scenes of the tremendous battles that brought about the undoing of the Sea Peoples unfold. How could enemies so strongly entrenched around Egypt and so well established even in the Nile Valley itself have been defeated so completely? For after the victories of Ramses III they never again represented a serious danger to Egypt.

Invaders Repelled

To understand the brilliance of Ramses III’s tactics, one must recognize the patience, care and tenacity with which he pursued his policy of reconquering Asia. The triumphant bas-reliefs of Medinet-Habou indicate a first expedition dating from the third or fourth year of his reign, or perhaps even earlier. This was against the Amorites and the inscription reads: “The capital is reduced to ashes, the people taken into captivity, their race obliterated.” Ramses III may well have used this opportunity to march against the Libyans and the Asians who, he said, had been the ruin of Egypt on former occasions. Perhaps he also stopped the Delta invasion of two new Indo-European bands of troops, who had come from Libya in swift warships and were disembarking along the coast.

This counter-blow, however effective temporarily, could not deter the aggressors, who were themselves being pressed by their own enemies. In the fifth year of Ramses’ reign Libya was the scene of a concentration of hostile tribes, among whom were the Mashouash — who were beginning to acquire an alarming hegemony — and the less numerous Seped and Rebou. The Libyans had been restive ever since Ramses II, in order to assert his authority over this area, had installed as king a Libyan prince brought up in Egypt and loyal to the Pharaoh. The adherents of the legitimate Libyan dynasty overthrew this foreign intruder. Then, after summoning to their assistance all the scattered tribes of the Sea Peoples, they attacked the Egyptian garrisons at a place believed to be Canopus, where the Nile debouches. Their intention was to push on from there as far as Memphis.

Ramses III quickly surrounded the invaders, trapped them in swampy ground and slaughtered them so effectively that it would seem the whole race of the Sea Peoples must have been destroyed. However, the satisfaction gained from this victory was short-lived. Scarcely three years later, in 1191 B.C., the Denyen, the Tjeker, the Peleset, the Shakalsha and the Washash, more insolent and bolder than ever and supported as always by the native population of Libya, the Tehenou, again attacked Egypt.

This war of 1191 B.C. finally broke the spirit of the Sea Peoples and disorganized their coalition. The tribes from Asia arriving by sea found the Delta protected by an Egyptian squadron much larger than any gathered there before. If one is to believe the accounts of the battle, each mouth of the Nile was blocked by ships close enough together to touch sides. Along the land frontier toward Palestine the Egyptians had built forts and had assembled a number of infantry regiments as well as squadrons of chariots. All the doors into Egypt had been securely locked.

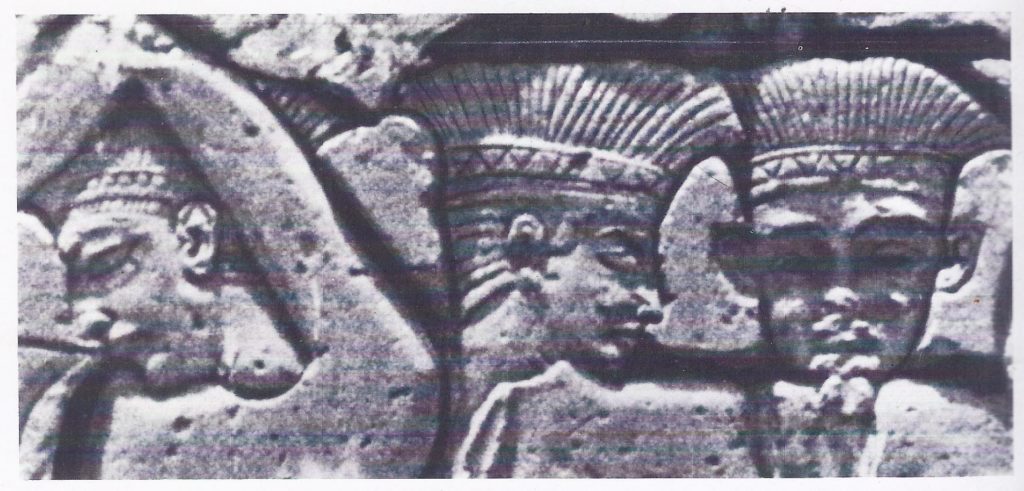

Ramses’ strategy was skillful: the enemy’s assault would be broken by these impenetrable walls and Ramses then would have only to drive back the discouraged and weakened aggressors to their point of departure. The bas-reliefs of Medinet-Habou show the fury of the naval battle. The Egyptian galleys rammed and sank the ships of the Sea Peoples, whose prows, like the Viking longships, terminated in birds’ heads; Egyptian sailors pierced with their lances the invaders, some of whom wore the horned helmets so characteristic of the Germanic nations during the later great migrations. The invaders, annihilated at sea by a better armed fleet and blocked by land, retreated. They left more than 12,500 dead and about a thousand prisoners. The enemy dead were counted by a curious system: each soldier cut off one hand (or the genitals, if uncircumcized) of his victim and took them to the scribes responsible for the census and rewards.

Ramses III wished his glory to be recorded for all time on the walls of his funerary temple and it is to this that we owe the magnificent and realistic battle scenes. The Pharaoh — larger than life, according to the convention for a figure already semi-divine in his own lifetime and after his death destined to be revered as a god — is piercing his enemies with his lance and crushing them with his mace. The sculptors have carved with great precision the racial peculiarities of the different peoples who allied together against Egypt: the projecting jaws of African Negroes, the Semitic noses, the feathered headdresses of the Philistines, the beards (presumably blond) and horned helmets of the northern tribes, huddled together in a single group, pitiful and suppliant. Elsewhere Ramses III, standing upright in front of a sort of rostrum, receives homage and reports from his generals, while lower down his secretaries count the corpses.

Power and prosperity in Egypt under Ramses III

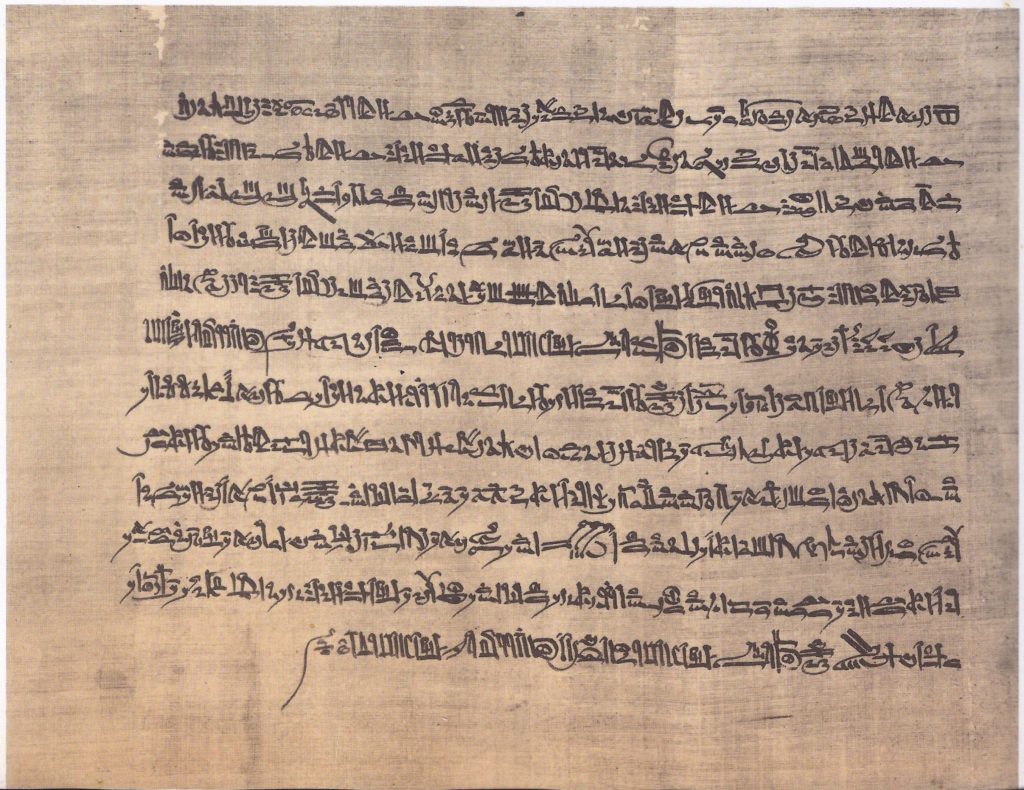

The victorious king was not exaggerating the glory of his successes. It is clear from the records of the Harris Papyrus and the inscriptions at Medinet-Habou that Egypt had escaped a catastrophe comparable to that which had wiped out the Hittites. Yet decisive as this victory was, it did not assure the impregnability of Egypt. Three years later, in the eleventh year of his reign, Ramses III had to take to the field yet again.

The Mashouash, who had occupied Libya and imposed their rule on the native Tehenou, had chosen as king a fearless and cunning tribal chief called Kaper. He first united all the small IndoEuropean tribes established in Libya and coerced the more or less reluctant Tehenou to join his federation. He then marched against the Egyptian frontier fortresses and pushed forward to within fifty miles of the Nile before being halted by the royal chariots. Once again Ramses III was able to put on his victory memorials the triumphant inscription: “The race of men who menaced my country no longer exist, they have been ground into the dust, their hearts and souls have disappeared for all time.”

We know from the inscriptions at Medinet-Habou that more than 2,000 Mashouash were killed and that survivors were pursued for more than twelve miles. Prince Meshsher, who commanded the invading army, was taken prisoner, along with a considerable number of his men: when Kaper, the vanquished king, came to entreat Ramses to spare his son’s life, they executed the prince in front of his eyes. Kaper himself was put in chains and condemned to slavery. The prisoners taken in the three campaigns (in the fifth, eighth and eleventh years of Ramses’ reign) provided the king with 62,226 slaves, whom he employed to build and maintain his funerary temple.

The unruly neighbours of the Two Kingdoms were henceforth politically impotent. Dispersed, denied the cohesion that had made them so dangerous, driven out of all Egyptian territories, the Sea Peoples were once again reduced to piracy by sea and a nomadic life on land. The prestige of Ramses III was immense and his authority indisputable. The subject nations once again began to pay him tribute and the sea routes once more were open to commerce. Ramses consolidated his empire by taking five cities of the Amorites and reducing the remnant of the Hittites in Syria to complete subordination. As for the Bedouins in Nubia, a few policing operations proved sufficient to reduce them to servility. Until Ramses III’s death in 1166 B.C. nothing disturbed the prosperity and power of Egypt.

Ramses’ personal life, however, was not so tranquil. In spite of the debt that his people owed him, showered as they were with glory and blessings, his life was endangered by several plots, one of which was engineered by his own vizier. At last, one of his wives, Queen Tiye, to further the covetousness and ambition of her son, resorted to a sorcerer who used magic charms and probably concocted poisonous drugs.

The plot was denounced and about sixty people, including six women, were condemned to death. Some of these were granted the favour of committing suicide; others were strangled or buried alive. The status and offices of the conspirators are known: a general by the name of Peyes, the commander of the Nubian archers, five senior officials, three royal scribes, five sculptors, the sorcerer Panhouibaounou and certain concubines. Ramses never knew the outcome of the trial: he died some days before the verdict, after a reign of thirty-one years and forty days.