The sun had broken through the clouds after a night of spring showers. Dripping leaves sparkled in the golden light, which flooded the gaily decorated streets of Versailles and the broad terraces of the king’s royal palace. It was May 4, 1789, the day of the opening ceremony of the recently elected Estates General.

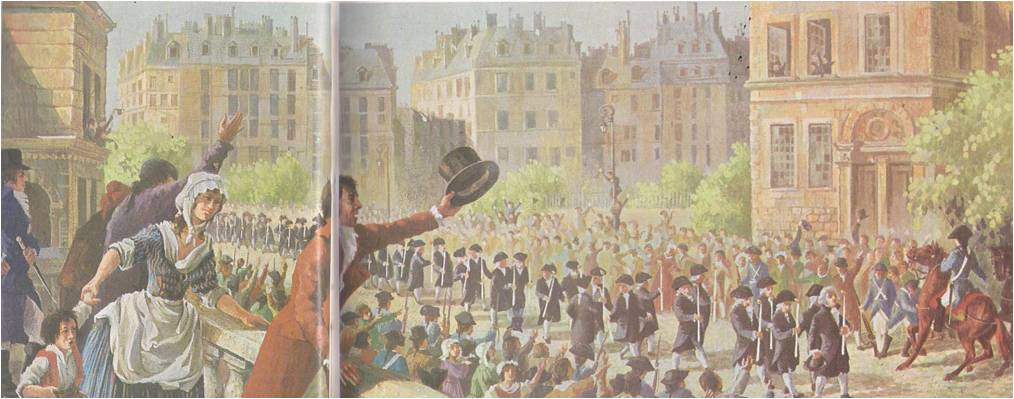

The streets were crowded with visitors, most of them from Paris, only a few miles away. They had come to see the grand procession of the Estates General and were in a holiday mood. The shops were closed. Local citizens watched from windows, crowded balconies and rooftops. This was a day, they felt, that would go down in history as the beginning of a wonderful new age for themselves and their country.

The procession moved slowly along the street in the direction of the Church of Saint-Louis, where a mass was to be celebrated. The representatives marched by two’s, each holding a lighted candle. First came the members elected by the ordinary people of France who made up the middle and lower classes. These were the commoners, usually referred to as the Third Estate. There were more than 550 of them, all dressed in black and wearing three-cornered hats.

Towering above the other marchers of this group was a man with a large head and an ugly face, a nobleman named Mirabeau, who had presented himself as a candidate for the commoners and had been elected as such. Almost all representatives of the commoners came from the middle class, which was made up of merchants, business and professional men from towns and cities. This middle class was called the bourgeoisie.

Next in the procession were the noblemen. They wore wide hats with plumes, Silk capes embroidered with gold, tight breeches and stockings of snowy white, with sparkling jewels on their shoes and fingers and swords. Lafayette marched with this group. As an elected representative of the nobles, he no longer felt free to express some of his liberal views, but he was pleased because the people could now speak for themselves through their elected representatives to the Estates General.

Marching behind the richly dressed noblemen came another privileged order, the leaders and priests of the Catholic Church. The priests wore their long black habits and were followed by the bishops and cardinals in colourful robes. Last of all came the royal family, led by the fat king. Next came the queen and behind her the king’s brothers.

The people cheered and waved as the king passed by, for they were still his loyal subjects. They had been ruled by kings for so many centuries that it seemed natural for King Louis XVI to be the head of their government. All three orders of society — nobles, churchmen and commoners — agreed that the king should no longer have absolute power to rule over the people. The time had come, they believed, to place certain limits on his powers. Since the Estates General represented all the people of France, it could probably force the king to give up some of his powers and make many other much-needed changes in the government, or so people hoped.

At the same time, each of the orders of French society hoped to use the Estates General for its own benefit. The nobles were very much interested in liberty, but they wanted it mainly for themselves. They had many reasons for being concerned about the future. There had been a time, long ago, when noblemen were the richest and most powerful people in France They owned the land and each noble ruled over his area of land as though it were a private little kingdom. His farm lands were tilled by serfs‚ who were really no better than slaves. They and their children had to remain on the land they were working. If they tried to escape, they were hunted down and brought back.

The nobles needed the help of the French king to defend their lands from each other and from foreign enemies. They paid for this protection by sending him money and men for his army. Gradually the French king had gained control over the lords and taken away much of their power. They were weakened still further when the serfs became free men and were at liberty to leave the farm lands upon which their families had been forced to live for centuries.

Many of these peasants had taken advantage of their newly acquired freedom by moving to towns to work for wages. Some saved enough money to buy land and go back to farming again, but on their own land. The nobles, most of whom managed their estates badly, were usually willing to sell some of their land to raise money. The more they sold, the less they had left and the poorer they became. Meanwhile, businessmen in the towns and cities were becoming rich. Advancements in science had made possible the manufacture of cloth and other items much more cheaply than ever before. In addition, France had become a colonial power. Her colonies supplied raw materials for her factories and provided large new markets for her manufactured goods. As a result, there had been a great increase in business activities during the 1700’s, with the profits going to middle-class people of towns and cities — manufacturers, merchants, bankers and professional men.

Many of these commoners had become very wealthy because of their business experience, they were often appointed to important government positions. Some served as ministers to the king. This angered the nobles, who felt that only nobles had the proper qualifications for high government posts. The nobles were alarmed when the king began raising money by selling various government positions to rich commoners. They were even more alarmed when he began selling titles, making it possible for many rich commoners to become noblemen.

The nobles had lost so much of their wealth and influence over the years that the American Revolution and the growing demands for liberty in France frightened them. They realized that all the special advantages they still enjoyed would soon be taken from them unless they fought to protect their interests. They had actually begun that fight with their revolt against the king which had forced him to call the Estates General.

The nobles expected to control the Estates General, with the help of the leaders of the Church, who were also noblemen like themselves. They wanted the Estates General to protect their special privileges, to provide free schools for their children and to halt the sale of public offices and titles by the king. They were also going to demand that all important positions in the government and in the army be filled only by noblemen.

Whether the nobles and churchmen, the two privileged orders, could control the Estates General depended upon the method of voting used. In former times, the voting had been by orders — that is, each of the three orders had only one vote. The nobles and churchmen were naturally in favour of this method, for it meant that together they could outvote the commoners two to one.

The commoners had another system in mind. They wanted to vote by head, which meant that each individual representative of each order would be allowed one vote. This method would balance the commoners with the privileged order, because the commoners had as many representatives as the other two orders put together. Furthermore, the liberals in the privileged orders would vote with the commoners of the Third Estate, thus giving them strength enough to control the Estates General.

The commoners felt it was only right that they should have control, for they represented ninety-six per cent of the people. They had been made aware of their importance by many writers. Abbé Sieyés had begun his famous pamphlet, What it the Third Estate? with these words: “What is the Third Estate? Everything. What has it been in the political order up to the present? Nothing. What does it ask? To be something.”

THE ESTATES GENERAL

Sieyés went on to point out that the commoners of the Third Estate had all they needed to make up a nation. “Take away the Privileged orders and the nation is not smaller, but greater. . . . What would the Third Estate be without the Privileged orders? A whole by itself and a prosperous whole. Nothing can go on without it and everything would go on far better without the others.”

This was the mood of the commoners at the opening session of the Estates General. They felt they had the support of Necker, the King’s leading minister, for he also was a commoner, but Necker said nothing in his opening speech to encourage them.

After the first meeting, each of the orders was given a special room in which to check the papers of its representatives. The nobles and churchmen went on to their special rooms and organized themselves as separate bodies. The commoners met in the throne room, but refused to do anything. They were afraid that if they took any action as a separate body, they would be forced into the old system of voting by orders. They argued that the Estates General represented all the people of France and that therefore it had to meet as one body and vote as one body.

For a month the commoners did nothing but in refusing to act they prevented the other two orders from going ahead with the business of the Estates General. Privately, some of the commoners urged representatives of the Church to join them, for the church group was known to be the weakest of the three orders.

The Church itself was powerful, well-organized and owned about a tenth of all the land in France. Although it paid very little in taxes, it often donated large sums of money to the king for the support of the government. It was in charge of all schools in the country and of relief for the poor. It had its own system of courts, where offenders against the faith could be tried and punished. It had power over the press, since it could decide what should be published. It also kept the public records of all births, marriages and deaths within the kingdom.

The income of the Church came from its lands and from a church tax, called a tithe, on all farm products. The peasants who had to pay this tax might not have complained about it so bitterly if most of the tax had been used locally for the parish church and for local welfare and education. Instead, the local priests were given so little that the parishes were always in desperate need. Most of the tax went to central church offices and to the bishops, many of whom lived in princely fashion in Paris, far from the churches under their care.

The men who represented the Church at the Estates General fell into two political groups. The bishops and abbots, being noblemen, shared the political views of the nobles. The parish priests, who were commoners and worked very closely with the people and knew their needs, shared the political views of the commoners. The writer Sieyes pointed out that the religious order was not really a social class at all, but merely a professional group. There were actually only two classes of society represented at the Estates General — the nobles and the commoners.

On June 17, after a few parish priests had joined them, the commoners declared themselves to be the National Assembly. They invited the other orders to join the Assembly and began acting at once on problems of the day as if they were the representatives of the whole nation.

The bishops and nobles became alarmed and appealed to the king to deal firmly with the commoners and bring them back to their senses. The king decided to do this at a royal session in which the three orders would be brought together so that he could lay down rules for the Estates General to follow. On June 20, when the commoners gathered at the hall where they usually met, they found the doors closed. They were told that the ball was being made ready for the royal session, but they suspected that the king was trying to put a stop to their meetings. Rain was falling and they took shelter in an indoor tennis court nearby. There the determined delegates took an oath “never to separate but to meet in any place that circumstances may require, until the constitution of the kingdom shall be laid and established on secure foundations. . . .”

THE TENNIS COURT OATH

The Oath of the Tennis Court, as it came to be called, made it clear that the National Assembly meant to carry on its work, and would defend itself even against the king, if necessary. The commoners were in revolt. They had created a new representative body in which the privileged orders had no special advantages.

Most of the parish priests, as well as a few liberal bishops and nobles, had joined the National Assembly by the time Louis XVI held his royal session on June 23. The king brushed aside all that the commoners had done in the National Assembly. He set up rules for the Estates General to follow, agreed to a few demands of the commoners but warned that the social orders and the privileges of nobility were not to be disturbed. If the commoners failed to co-operate, he warned, he would dismiss the Estates General. He commanded the orders to separate at once and to begin their work in the three halls assigned to them.

The commoners stubbornly remained where they were, even after the king, the nobles and some of the churchmen had left. They were reminded by the master of ceremonies that the king had ordered them to leave the hall. Mirabeau spoke for them all shouting at the top of his voice that they were there by the will of the people and that they would not leave except at the point of the bayonet. Royal guards were ordered to clear the hall, but a few liberal noblemen convinced them that such action was unwise.

Now it was up to the king to decide whether to crush the rebels or to allow them to have their way. His royal guard could no longer be trusted to carry out his orders. For several days he took no action, for without the help of the guard there was not much he could do. During this time most of the churchmen and some of the nobles joined the commoners in the National Assembly and finally the king yielded again. He ordered the nobles and bishops to join the others in the National Assembly.

The successful revolt of the commoners had brought into being through peaceful means an assembly that represented the whole nation. The Assembly changed its name to the National Constituent Assembly and began writing a constitution for France.

Had the Assembly been able to continue its work undisturbed, it could probably have set up a constitutional form of government under the king without bloodshed, but the king and the nobles had not yet given up. They were determined to prevent the destruction of the privileged orders by the commoners. They must break up the National Constituent Assembly — and to do that they would have to use force. Since they could no longer trust the French soldiers, the king secretly sent for units of professional Swiss and German troops that were stationed in other parts of France.