In the last years of the fourth century B. C., Greek citizens going about their business in the stoas or the shops sometimes stopped and wondered what was wrong. Everything seems strange. They themselves had not changed and their cities looked the same as before, but the world around them was so different that they could hardly recognize themselves.

The little poleis on the mainland looked out at an enormous empire, which stretched across Asia and Egypt. They shipped their olive oil and pottery across the Mediterranean. Their corn came from fields beside the Black Sea and the Nile. Merchants who crowded their market places now did business in Antioch and their sculptors had gone to Alexandria. There were new Greek cities, thousands of miles from Greece, where Asians spoke Greek and Greeks began to dress like the barbarians. There were no barbarians now, only the many sorts of people who shared a world which Alexandria had conquered for the Greeks. As the world the Greeks knew became larger, a man and his city seemed to become smaller. The Greeks began to wonder if there was a Greece at all any more.

Athenians who travelled on business saw Athens in a new way when they came home. It was not very big and not very busy. When they went to the Assembly, the fine speeches had a hollow ring. In the old days, when Pericles or Themistocles spoke to the Assembly, things happened and the world felt the difference. Now, a man who spoke out in Athens might as well have dropped a pebble in an ocean.

Alexander’s empire was much too big to be run by a group of citizens who talked over their problems in an Assembly. One man could rule it, if he was a king like Alexander and had a strong army. When Alexander died, the strongest of his generals split the empire into three pieces, each bigger by far than Greece. Each was ruled by a despot, an all-powerful king whose word was law to millions of people who would never see him.

In Egypt, the sons of the general Ptolemy began to call themselves Pharaohs and gods. The Seleucids, another military family, took most of the old Persian lands. Macedonia and Greeks were claimed by the general Antigonus.

The Athenians were ready to fight for their independence, but they knew that their city was too small, too weak and too tired to hold off a despot’s well-drilled army. Worse than that, they realized that Athens was old-fashioned. In the empire that Alexander had left behind, a city that acted like a country was a joke.

At the barber shop of the Assembly, the talk was always the same. “Fifteen years ago…” someone would say and the others would nod in agreement. “Yes, fifteen years ago, a citizen of Athens knew where he stood.”

Fifteen years ago, before Alexander had changed the world, the polis had been everything. A citizen was protected by it, worked for it, taking on jobs in the government. His life was comfortable and he lived with honour. If he wrote a story, composed a song, or carved a statue, he did it for the glory of Athens and earned a little glory for himself, too. Now Athens did not matter. Nothing was glorious.

The talkers would shake their heads and wander away to talk to other men, who would say the same things again. Alexander had promised to win a world for them. instead he had taken away the one world they knew. The Greek poleis were dying and Demosthenes’ strong and independent Greece was already dead.

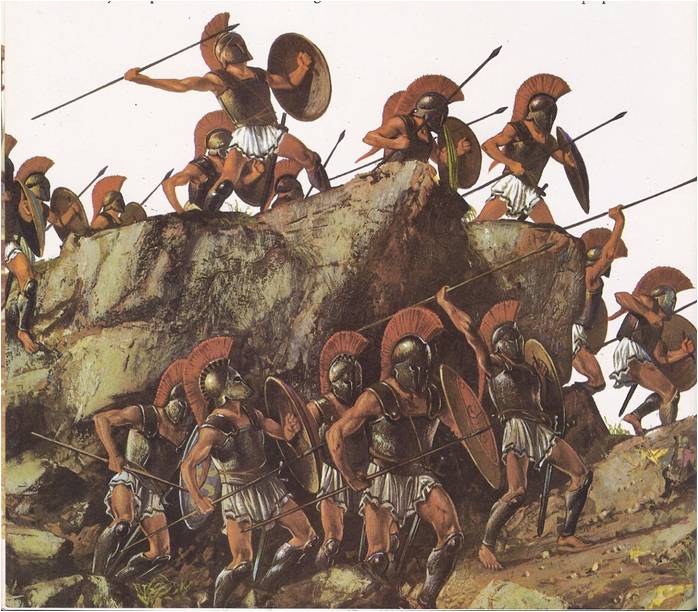

Many of the Greeks found comfort in thinking of the good old days, when Greece had been the home of heroes. They read Homer again and filled their houses with statues and paintings of his warriors. They learned to sing old folk songs and collected antiques – bits of rusty armour and old pottery. They did not care what it was, so long as it reminded them that once the Greeks had been powerful and life had been good.

Some Greeks looked to the gods for help. Day after day, chanting and the piping of flutes filled the streets, as hundreds of men and women followed the priests to the temples. They made their sacrifices, tried to obey laws of their religion and hoped that when they died they would be taken to the “Isles if the Blessed,” where heroes lived forever.

The Asian Gods

It was hard to believe that the old gods on Olympus cared what happened to them. The gods of Asia made better promises and many Greeks turned to them. Some of the new gods were beautiful, like the Egyptian Isis with her gentle eyes. Some, like the sun god Amon, were frightening, but all of them could foretell the future and all of them guaranteed their followers a happier life in a paradise that was just the other side of death. That was cheering news to the Greeks who were frightened of the future and dissatisfied with their life on earth. They flocked to the shrines of the new gods, luck charms around their necks and forgot their cares in dreams of the wonderful life after death.

In the meantime, the once plain-living Greeks were taking an interest in fine clothes, fancy furniture and banquets. If their cities no longer gave them important things to do or think about, they could atleast spend their time enjoying themselves. They began to listen to music and poetry just because it was beautiful and delighted in stories that made them laugh instead of teaching them a lesson.

A new kind of comedy was playing at the theatre. Politics was no longer a laughing matter, but Athenians could laugh at themselves – or, better still, at the fellow next door. Menander the best of the new playwrights, kept Athens chuckling at the funny things which might have happened in any house in the city. There were pinch-penny fathers with sharp-tongued wives and girl-crazy sons who tried to trick them out of their money. Sly servants got everything into a tangle, then stopped to tell jokes and the audience howled.

Serious-minded citizens saw little to laugh at anywhere. The people walking in the groves beside the playing fields wore long faces and their talk was gloomy. Once they had listened to men like Plato and Aristotle. They had hoped then to understand everything in the universe. Now they hoped for nothing and listened only to teachers who told them how to make the best of things.

One group, a circle of men who called themselves the Cynics, said that the only way to get along was to play it safe. Their first teacher, Antisthenes, recalled that Socrates had said: “Nothing which does not make a man worse can hurt him.” So Antisthenes and his students set out to avoid anything that might make them worse. Money was the first thing they put on the list, then art, science, poetry, politics and music. Each time they talked together, the list of things grew longer, but they were proud to say that they were learning to do without them all.

Diogenes

With their untrimmed beards and ragged clothes, the Cynics were a sour-faced, odd-looking lot. The oddest of them all was Diogenes of Synope, who did without almost everything. It was said that he gave up his house and lived in a clay jar about the size of a bathtub. People told of meeting him roaming the streets in broad daylight with a lighted lamp. Diogenes explained that he was searching for an honest man. When Alexander had once visited Athens, he wanted to see this strange philosopher who said that the world’s riches were hateful. He found Diogenes sunning himself in the market place and offered to do him a favour, anything he asked for. Diogenes looked up at the great conqueror. “A favour?” he said. “Yes. Move over – you’re cutting off my sunlight.”

A very different kind of man was Epicurus, a teacher who chatted with his students every afternoon in a quiet garden outside the city. Epicurus said that Diogenes and the Cynics had the wrong idea altogether. “What is the use of trying to make life safe by running away from everything that makes life good?” he asked.

There were no sour faces in Epicurus’ garden, for he told his students that the secret of a good life was learning to enjoy life’s pleasures. While the men sprawled on the grass and talked together pleasantly, like old friends, he tried to teach them to avoid the things that could spoil their pleasures. He especially tried to teach them not to be afraid. Most men feared death and what came after, but Epicurus said that they were wrong to feel frightened. He told his students that when people died, the atoms of which they were made sprang apart. Then they did not exist, so they could not be hurt and need not be afraid. They had every good reason to enjoy things while they were still alive.

“Eat, drink and be merry, for tomorrow you die!” was the way some people put it and used this philosophy as an excuse to be greedy. That was not what Epicurus meant at all. He warned his students that too many pleasures were as bad as none at all. “Pick and choose,” he said. “Art, poetry, knowledge and good friends are pleasures that will not fail. Anger, greed and fear can be avoided. Wisdom, like our garden wall, will shut them out.”

Zeno the Stoic

There were some men in Athens who had no wish to hide behind the garden walls. They went to listen to Zeno, a young man who came to the city as a merchant and stayed to be a philosopher. Zeno’s friends were statesmen, officers and men of affairs. Their meeting place was a stoa in the busy market and so they were called the Stoics. Zeno said he was tired of hearing Athenians whine that they had no strength or freedom because their city was weak. He told them they had a strength of their own, in their ability to reason like men. He reminded them that no tyrant could really conquer their wills. When people came to Zeno with fears or sorrows, he told them to forget them, because such things simply did not matter. He tried to teach them why this was so.

“There is a wise god,” Zeno said, “who has the plan of history in his mind. The plan is like an endless story, with a little tale about every nation, man, or insect that will ever exist. We men can never understand the whole story, but we can use our reason to discover out own tales, the tasks which are ours to do. When we find them, it is our duty to do them well and to meet every hardship with one thought: ‘If it is God’s will, it is my will, too.’ Then pain and grief will not matter. We can ignore them.” It was easy to say and hard to do. A man needed a strong will indeed to remind himself that a pain which tortured him did not matter because it was only part of a plan. Zeno’s ideas gave courage to men who had begun to feel small. Many Athenians became Stoics. They squared their shoulders and showed the great new world that there were some Greeks in it who were not afraid.

Those who were ambitious did not stay long in Athens. They followed the crowds to Antioch and Alexandria and the other big cities across the Mediterranean. These cities, built by Alexander, were not like Athens. None of them tried to be a country or called itself a polis. The new word was cosmopolis, ”a city of the world.”

Passengers bound for Alexandria could tell, long before the ships reached port, that they were coming to a place like none they had known before. During the night, far out on the sea, they caught sight of the bright beam of light from the beacon in the harbour. When they docked in the morning, they passed the lighthouse itself, looming above them, forty stories high. It was a wonder of design and engineering, but it was only an introduction to Alexander’s first and greatest city.

Alexandria

The streets of Alexandria were straight and long. Two avenues, a hundred feet wide, crossed at the city’s centre. They were lined with porches, whose roofs were held up by endless rows of columns. Visitors strolling in the cool shade of the porches could see above them the royal palaces and the magnificent Mausoleum, where the body of Alexander lay in an alabaster coffin. If the strangers’ business was official, they would enter one of the huge blocks of government offices, just off the avenue. Otherwise, they might refresh themselves after their journey with exercise in a gymnasium or a swim and a snack at the public baths.

Wherever the visitors went, they heard a babble of languages, for Alexandria was the trading centre of the world. The people of Africa, Asia and Europe mingled in its streets. They traded together in its market place and warehouses, lived side by side and forgot that their nations had once been separated. That had been Alexander’s dream. When he had planned his city, he had set aside space for temples to honour the gods of Greece, but he also made room for shrines to the Egyptian goddess Isis. He started the famous library, where the books of Greece and Asia were collected and he built the Museum – a temple of the Muses – that became an international university.

Exploring Science

In Alexandria, people were interested in practical things – weights and numbers, dollars and cents, shapes and sizes. The scholars at the Museum looked at things in the same way. They were scientists, practical men who looked for practical methods of finding answers to the most difficult questions. They asked: How big is the moon? How small is the tiniest living thing? What is the earth made of?

Many of their questions had never been asked before. The scientists were explorers, searching out the mysteries of the world in which man lived. There were no maps to guide them, but Aristotle had left them a kind of rough sketch. He had marked off the territories, the kingdoms of animals, medicine, stars and the rest. His students had learned to look and measure and count. “First put things in order,” he had told them. “See how they fit together.”

One of Aristotle’s pupils, Theophrastus, was still in Athens, examining the strange Asian leaves and flowers which Alexander had ordered his scientists to collect for this old teacher. Theophrastus set the odd plants side by side, studying their likenesses and differences and tried to discover how they were related.

The scientists at Alexandria studied other regions of knowledge. There was no Plato to tell them to fit everything into one great picture of the universe. Instead, each man had his field and the more he studied, the more details he found to interest and excite him. Every science seemed to be as complicated as a universe.

Plato’s student Euclid came to the Museum to work out his laws of geometry. Then he put his lessons in a book, the Elements and the job was done for all time. His young pupils always hoped there might be some easier way to learn geometry. When they complained, Euclid added one more to the list: “There is no royal road to geometry.”

Scientists in other territories had trouble finding their roads at all. Often their greatest discoveries came by accident. Archimedes of Syracuse stepped into his bath one morning and noticed that as he sat down the water rose higher in the tub. He lifted out one foot and the water went down slightly. He plunged his foot back into the water and again the water rose. He tried it several times, then suddenly he bellowed – “Eureka – I have found it!” His servants, sure that he was drowning, rushed in to save him. Archimedes smiled at them over the tub. He had just discovered a way to measure the weight of ships. It could be done by calculating the weight of the water displaced by a floating ship.

A bathtub was as good as most of the makeshift tools which the Museum’s scientists had to work with. They had no lenses for microscopes and telescopes, no thermometers, no equipment for measuring things accurately. They put together gadgets of string, sticks and bits of bronze and got on with their investigations. When Archimedes went home to Syracuse, he was able to dumbfound his king with his discoveries. He rigged a series of pulleys which allowed the king to hoist a ship onto a dock simply by turning a crank. Then he showed them how to use a pole as a lever to move a rock which eight men could not lift with their hands.

Another scientist, Erastosthenes, was able to estimate the size of the earth by measuring the shadows made by the sun at two places in Egypt, 700 miles apart. Then, Aristarchus of Samos went to work on a method for measuring the sizes and distances of the sun and moon. None of the other scholars paid much attention to him, because he had a crazy idea that the sun was the centre of the universe and the earth revolved. It was nearly 2,000 years before astronomers found out that he was right.

In the meantime, everyone followed the ideas of the greatest of the Museum’s stargazers and map makers, a man who was called Ptolemy, though he was not of the Egyptian kings’ family. Ptolemy mapped out the universe with the earth neatly in the centre, surrounded by the planet and stars. There were more than a thousand stars on the map, most of them discovered and named- without the help of a telescope – by Hipparchus, an astronomer at Rhodes.

Hipparchus made many discoveries. He was the first man to figure out the exact length of a year by watching the movements of the sun. He invented the lines of latitude and longitude which the geographers used when they drew maps on earth. The new maps were big, for explorers were roaming far now. Some of the reports they brought back from their expeditions were not easy to believe. When Ptolemy made a world map to go with his map of the universe, he put in the Atlantic Ocean and the newly discovered islands of Britain. He refused to include the “Sea of Jelly”, the sailors’ name for an ocean crusted with ice which they had found far in the north. A man who knew only the warm waters of the Mediterranean could not imagine such a thing.

While the philosophers stayed in Athens and the scientists in Alexandria, the artists of Greece raced from place to place, trying to keep up with their orders. There was little work for them in Athens, but the rich new trading centres across the sea were eager to put up fine buildings and decorate their streets. When the architects and sculptors arrived, the orders were always the same: “It doesn’t matter what it costs, but make it better than Athens.”

The Colossus of Rhodes

The merchants of Rhodes, a wealthy island crossroads in the Aegean, spent their gold for great marble buildings and 3,000 statues by the finest sculptors. At the entrance to their harbour, they raised a mammoth bronze figure of the sun god, ten stories high. It was called the Colossus of Rhodes. Rhodes was outdone by Pergamum, a town in Asia Minor that came to be called the most beautiful city in the world.

From a distance, the Acropolis at Pergamum looked like a city of the gods that might suddenly disappear in a cloud. Closer, it was even more lovely. The Acropolis rose 900 feet in a series of terraces, with buildings of white marble set in gardens. There were statues everywhere. Many of them honoured a tribe of barbarians whom the soldiers of Pergamum had defeated in battle. In figures of bronze and marble, the fierce warriors fought again, so real that it was hard to believe that the faces, pulled tight with pain, could never change.

The Altar of Zeus

The wonder of Pergamum was the Altar of Zeus. There, the battle of the gods and giants was shown in a great carving, seven feet high and four hundred feet long. Many people said the sculpture was finer than the one at Athens which showed the same battle. There was an important difference, however. The sculpture at Athens was meant to do more than tell a story. It was supposed to remind the citizens of the struggle between human order and the stupidity of beasts. The splendid carvings at Pergamum only told the story.

Most artists only told the story now. That was what people wanted, statues that were beautiful and seemed real. They praised the softness of Athena’s mantle when they looked at Phidias’ carving in the Parthenon. They were even more impressed with the statue of an athlete carved by another Athenian, Polyclitus. He and his friend Praxiteles became famous for the grace and naturalness of their statues. Love, sorrow and death became the sculptors’ subjects.

Painters, too, tried to copy real things exactly. In Athens, two artists held a contest to see which of them could make the most realistic painting. Zeuxis painted a bunch of grapes which looked so real that birds flew down to peck at them. Parrhasius, his rival, looked at the wonderful painting, went home and a few days later invited Zeuxis to come and see a picture he had made. When Zeuxis, still proud of his grapes, walked into his friend’s studio, Parrhasius pointed to a painting covered by a curtain. Zeuxis walked over, reached up to draw the curtain, then quickly pulled his hand away. He had lost the contest, for the curtain he had touched was the painting.

Those who could afford them hurried to buy such marvelously real statues and paintings – portraits of the heroes, of famous men like Alexander, or of the gods in all their beauty. It did not occur to the buyers that some of the new figures had been made to stand oddly, as though the artists were only trying to show off their cleverness. They did not notice that sometimes the statues were too graceful and elegant. Like many Greeks, the artists were looking backward to the great old days, when men were almost gods. They remembered only what was pretty and forgot what was strong.

That was happening everywhere in the Greek world. Poets tried to write like Homer and Pindar. The stories were the same, but the new poems were failures. The only fine poet in all of Alexandria was Theocritus, who had better sense than to make imitations. He invented his own kind of pottery, which he called the pastoral. In the rush of the city, he wrote about his homeland, Sicily; and delighted the worldly-wise Alexandrians with his tales of sunny meadows, cheerful shepherds and romantic youths and girls.

Perhaps the Alexandrians were fond of the stories because they told about a charming world that was no longer real, like the world of Greece. That world, once real, was gone. It had disappeared with Pericles, Socrates and the strength of the little poleis that had worn themselves out. Now it lived only in statues, plays and books. Over 700,000 volumes were jammed into the great Library at Alexandria. Scholars pored over them. Scribes copied them so that libraries in all the new cities could have them. Every educated person read them, for the new world was learning Greek.

Centuries later, the people of the other new worlds would also learn Greek. They would read Homer and put up theaters for the plays from Athens. They would build temples which they hoped were like the ones on the Acropolis. They would run marathon races at their own Olympic Games and study science according to Aristotle’s rules. Sometimes they would think about the puzzle of Greece: a little nation that was never a nation at all had somehow conquered the minds of the world for all time. They would remember Pericles, who once told his Athenians: “Future ages will wonder at us, for our adventurous spirit has taken us to every sea and country; everywhere we have left behind us ever lasting monuments.”