IN 29 B.C. the gates of war were closed. Rome was at peace.

Senators and the people of the mob-men who had hated and fought each other through long, bitter years — stood side by side in the Forum while the great doors of the temple of Janus were slowly pushed shut. That had happened only twice before in the history of the city.

The crowd in the Forum cheered the peace and they cheered Octavius, their new ruler. He was no longer the young man who had rushed to Rome after the murder of his uncle, Caesar. Seventeen years had passed since then — seventeen years of hard campaigning, of friends who became enemies and of alliances that were broken. He was still handsome and his sharp eyes could still look through a man. He walked with a new dignity that won him the respect of the people and Senate alike. Wherever he went, cheering crowds followed him. His friends told him that he could make himself the king of Rome. Octavius remembered what had happened when Caesar had thought of becoming a king.

Caesar had proved that one man with an army could do what the bickering Senate and the mob could not do: he could run the empire. A world with millions of people in it was still like the smallest Roman family; it worked best with only one pater familiar. Octavius meant to be that all powerful father of Rome, but he intended to let the Romans think that they had asked him to be it.

He celebrated his Triumph with processions that went on for three days. With the treasures he had won in Egypt, he bought land to give to his soldiers. He ordered the building of a splendid temple to Apollo, as he had vowed he would before the battle at Actium. Then he gave up all his powers as a military commander and officer of the state. “Once more the laws of Rome are in the hands of the people and the senate,” he said.

The Senate, however, rushed to ask him if he would not, at least, accept the command of Gaul, Spain and Syria. He did and that put him in charge of nearly all the legions. In gratitude, the Senate gave him a laurel wreath for saving the lives of citizens, a golden shield, and the new name Augustus. It was a name of honour that had been given only to gods before, but in the eyes of Rome, this man who had brought peace was a god. Then the Senate elected him princeps. It was a new office and the name meant “the first”— the first citizen of Rome. Years later, the word came to be “prince,” for that is what Augustus made it mean.

AUGUSTUS REBUILDS ROME

By their votes, the Romans had made Augustus more powerful than any king had ever been, but he was careful not to act like a king. He kept the old custom of wearing only clothes made in his own household. He lived in a house that was smaller and less elegant than the homes of many of his citizens. He made a great show of consulting the Senate before announcing any decision. Elections were still held to name consuls, tribunes and the rest, though somehow Augustus’ men always won and often he was elected to one or more of these posts himself.

He was just as careful to see that nearly everyone had something to be grateful for and little to complain about. His soldiers’ pay was good and they could look forward to gifts of land when they were mustered out. The knights, his businessmen, were making money faster than ever before. The senators were happy with jobs in the provincial governments and appointments to the highway Commission, the grain council, or one of the other committees he had started. The mob was well fed and too busy to make trouble.

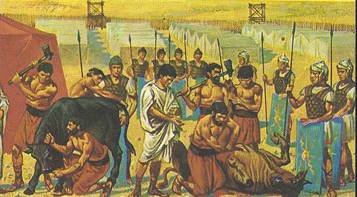

Keeping the mob busy meant giving free shows. Augustus, usually a cautious spender, paid out vast sums of money for the people’s entertainment. Ten thousand gladiators fought in the arenas during his reign and he presented twenty-six wild-beast hunts in which 3,500 animals were killed. Each show went on for several days and in one year, any Roman who had the stomach for it could have spent as many as 117 days in the grandstands of the arenas. Augustus’ greatest show was so enormous that no stadium in Rome was big enough to hold it. The stage was a gigantic pond, which he commanded to be dug in a field outside the city. Thirty warships were hauled to the pond and 3,000 prisoners manned them and fought a naval battle for the amusement of the Romans. No one but Caesar had done anything like that before. No one but Caesar had dreamed of changing the look of Rome as Augustus did.

The temple of Apollo was only the first of his projects. He built it entirely of the finest marble and, because Apollo was the bringer of light and knowledge, Augustus had two libraries built beside its entrance — one for books in Greek, one for books in Latin. Then he began to repair and improve all the temples in Rome. More than eighty of the old shrines were rebuilt and they glistened with new marble and fresh stucco. A series of great new buildings rose on the Campus Martius. One was a splendid temple for the gods of the stars and planets — the Pantheon. The old Forum was refurbished and two new market places were built, the Forum of Julius and the Forum of Augustus. Wherever the Romans looked, there was another building crew at work. They began to say that Augustus had found a city of brick and made it a city of marble.

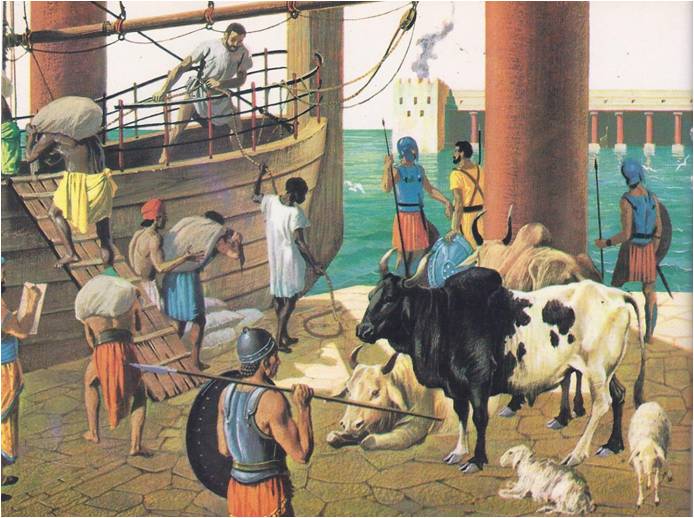

The new buildings were only one sign of the changes in Rome. Peace had increased trade and the city was rich. Ships and long caravans of mules and camels came to Italy loaded with cloth, spices, fine furniture, silver vases and dishes of gold. The ships brought people, too. Freemen from all the provinces poured into the city, looking for work and places to live. Tenements of brick and wood were hastily put up along already overcrowded streets. Rome was booming, and all the old problems of big cities — traffic and fire and crime-were worse than ever. Augustus solved them. For the first time Rome had a police force to keep order in its streets and a fire department that did not belong to a Crassus.

THE NEW RICH

He was less successful when he tried to curb the wild spending in his city. Augustus firmly believed that the old-fashioned Roman way was the best way. A man lived simply, because luxuries would make him soft and his money was something he put to work. Times had changed and the Romans did not agree with Augustus. Never had there been so much money and never had people worked so hard to spend it where it would show. Gone were the old noble families whose strict codes and plain living had built the Republic. Instead, men won fame with their riches. The city honored them, artists tried to please them and poets flattered them, even though they might laugh at their extravagance behind their backs.

A huge house in town was no longer enough. By Caesar’s time, anyone who was at all important had to have a villa, a sprawling estate in the country. In those days, Cicero, whose fine letters were filled with reports and gossip about the great men of his era, wrote about his brother’s country house, a place which Cicero said was worthy of a Caesar. It had a sunny promenade and a colonnade for strolling, an aviary filled with rare birds, a wrestling ground, a fish pond and a garden dotted with ivy-covered Greek statues.

STATUES AND BANQUETS

Cicero did not live to see the merchants who became millionaires soon after Octavius became Augustus. All of them wanted to live like Caesars. Suddenly, men who had longed for years to be important could afford to buy a place among the aristocrats and the great men who had ignored them — and they wanted the world to know it. Recklessly they poured out money for big houses, for draperies of Tyrian purple, for ivory couches and golden vases and for genuine Greek statues. It did not really matter to them that many of these statues were only copies. The marble was Greek; so were the designs and the names of the artists. It was said that every Greek who could lift a hammer had turned into a sculptor. Those who did not copy statues specialized in carving stone portraits of citizens and their wives. With eyes as sharp as their chisels, they copied every line and bump of a face. But their clients never complained — if a man was a Roman, he had no need to be handsome.

The sculptors kept shop in little stalls along Rome’s miles of colonnades, beside the Indian jewelers, who did a rushing business in diamonds, rubies and pearls. There, too, were the food merchants, who searched the world for new delicacies rare and expensive enough to suit the tastes of the people who gave banquets to impress their friends. Roast peacock, presented to the diners on a silver tray decorated with its tailfeathers, was a common dish. So was the whole roast boar, carried in from the kitchen by four or five slaves. An impressive dinner had to have dozens of such dishes — whole fish cooked in a sea of shrimp, meats with spiced vegetables, meats with sauces, oysters with sauces, broiled blackbirds and wood pigeons, Spanish wildfowl stuffed with Indian rice, berries still sparkling with the morning’s dew, peaches from Persia and Greek wine to fill the golden goblets.

“We rise from table pale with overeating,” the poet Horace wrote when he came home from one such dinner. He also said that the tablecloths were dirty.

Horace knew his way around Rome. His father had been a slave who earned his freedom, made a fortune and bought his son the best Roman-Greek education. By the time Horace grew up, he had seen every side of the city and it had few surprises for him. But wherever he went, he found something that amused or annoyed him. There was a young man tugging nervously at his very fancy, very new toga; and the banker’s wife, who wore too much jewelry and too short a skirt. There was the man who put on the airs of a gentleman and stole a chicken leg from the plate of the man who sat next to him at dinner. Horace put them all into poems, with a good dose of laughter and common sense. Comic luxury and dreadful poverty rubbed shoulders in the streets of Augustus’ city and the gay life of the rich was very different from the misery of the poor in the crowded slums. Horace could not call all of it good, but it was all a part of the adventure of Rome. In his poems, called Satires, Epistles and Odes, he poked fun at the Romans and lectured them too. The lectures won him the favor of Augustus, who asked him to be his private secretary. Horace refused. It would have taken up most of his time, and it would have confined him to the City.

Sometimes the city was too much even for Horace, and then he would flee to his cottage in the country. Not the Princeps himself could persuade him to give up his peaceful vacations, during which he could relax on his quiet hill and shock his friend Virgil with the latest tale of the scandalous doings in Rome.

VIRGIL’S EPIC POEM

For Virgil, who was also a poet, the city was no adventure; it was a horror. He said that the good Rome and the good Romans — the kind of men who had won the world — could only be found now in the smaller towns and countryside of Italy. When Virgil wrote poetry, it was about the open fields and the clean air he loved. His first long poem, the Georgics, told of the joys of planting and harvesting and of the men who were Rome’s strength. When Augustus heard him read the poem, he was delighted, for this was the Italy he loved, too. Like Virgil, he had been raised in a little country town. He, too, believed that Rome’s hope was in the land and in a return to the old ways, which the city people had forgotten.

Virgil decided to write a book for Augustus. He would tell the story of the founding of Rome, in an epic poem, like the ones that Homer had written. It would honor Augustus and show all the world that his nation, like Homer’s Greece, was a land of heroes. Virgil began with the story of Aeneas, who, he said, was the ancestor of Caesar and Augustus. For eleven years he worked to make his poem as great as Rome itself, but he was never satisfied with it. When he was dying, he ordered his friends to burn it. It was not good enough, he said, not good enough for Augustus and Rome. But Augustus commanded Virgil’s friends to send the book to him. Soon all Rome had read it and later it would be read by all the world. The Aeneid, as Virgil named it, became as famous as the Illiad and the Odyssey and Virgil was called the Homer of Rome.

THE LUXURIOUS LIFE

Augustus had his own reasons for saving Virgil’s poem. He hoped it would remind his people that courage and not easy living, had won them their riches. It worried him that they could forget so much so easily. He was delighted when his historian, Livy, tried to stir up the old patriotism by writing the true stories of Rome’s triumphs, from Romulus to Augustus in 142 volumes.

The Romans loved the Aeneid and they read Livy’s history, or at least some of it, but they did not give up their comforts. Old Cato had been right — the riches of conquest were conquering Rome. Augustus was horrified to see that parents no longer taught their children Roman discipline. They laughed at traditions, forgot their ancestors and ignored the gods. For many people, the idea of the family and its pater familias had become a joke. Elegant ladies collected husbands as eagerly as rich men collected statues. They turned love into a contest, a game they played just to keep busy.

Catullus, a young man who came to Rome in Caesar’s time, had not understood the rules of this game. He loved only once. When he met Clodia, one of the grandest ladies in the city, he knew that she was the most beautiful woman he had ever seen. He was young and of no importance; she was ten years older than he and the most famous people in Rome were her friends. Catullus dared to send her a poem. It was a cautious little poem about a bird she kept in her house. When Clodia read it, she did not become angry. Instead, she asked him to write more poems for her. Then, because they were good poems and Catullus was as handsome as he was young, she fell in love with him. After a time, she fell in love with someone else. Catullus could not change his love that easily and he could –- not forget her. He wrote more poems — bitter, sad and still full of love. Only Sappho in ancient Greece had written such love poetry before.

By Augustus’ time, the young men who came to the city had learned the rules of the game very well. They had money and little to do with their time. That gave them the chance to follow what the Greek philosophers called their “individual pursuits.” For young men — and some who were not so young — that usually meant the pursuit of women. When they needed advice, they turned to the verses of Ovid‚ a poet who wrote of love in a quite different way.

Ovid’s book, The Art of Love, was a set of instructions in romance, elegantly phrased but very clear. Chapter One told “How to Find Her”; Chapter Two, “How to Win Her”; Chapter Three, “How to Keep Her.” For women, there was a special section, “How to Win Him.” A little later, Ovid published a second volume, “How to Get Rid of Her (or Him).” The books set all of Rome chuckling and winking until Augustus banished the poet for having written them.

Ovid was shipped off to a little town on the Black Sea It was lonely there and very far from Rome. He wrote no more about love, but he a great book of stories, the Metamorphoses. In it he retold the old myths, such as those of Narcissus, who sat so long admiring his own reflection in a pool that the gods turned him into a flower and of King Midas, whose touch turned everything to gold.

Ovid was not the only light-headed Roman who found himself in trouble with the Princeps. Augustus banished his own granddaughter for her scandalous behavior. He wrote new laws to limit spending and wild behavior in the city. One of his laws even limited the quantity of wine a man could drink with his dinner, but such laws did little good. The Romans did not learn to behave or save their money; they simply learned not to get caught. Augustus, who could usually find a solution for any problem, failed to turn his giddy citizens into sober, old-fashioned Romans he wanted them to be.

THE FATHER OF HIS COUNTRY

Changing the world was a much easier job. The problems of the empire were practical ones and Augustus tackled them with the same good sense that helped him straighten out the politics of Rome. He cleared the roads of robbers and chased the pirates off the sea routes. One by one, he took charge of the provinces himself. No one objected, because the governors he appointed took their posts to govern, not to loot. They were the beginning of a civil service, a corps of men whose lives were spent managing the affairs of government.

Above all else, Augustus kept the peace. Farmers could plant their fields, certain that the crops would not be trampled or burned by armies lighting civil wars. The streets of Italian cities no longer echoed with the frightening sounds of marching feet and harsh commands. Augustus gradually pulled his legions out of the peninsula and then out of the provinces. He sent them to the frontiers, to guard against the barbarians and jealous eastern kings who threatened the new peace of the empire.

Augustus himself went to inspect the defenses and to visit the cities that now called him their only ruler. He returned with an idea for one more project — an Altar of Peace. He chose to put it on the Campus Martins, the field that from ancient times had belonged to the god of war. On the sides of the temple in which the altar would stand, he had his sculptors carve figures of Aeneas, Romulus and Remus, the Goddess Roma and the goddess Earth. Then, around the top of the building, binding Earth and Rome and its founders together, he had them carve a procession of triumph. It showed Augustus leading the people as they took their offerings of thanks to the gods who had given them peace.

There were many people in the empire who thanked Augustus as well as the gods. On one of his journeys, when his royal yacht passed an Alexandrian merchant ship, he saw that the passengers and crew were lined up at the rail. They were dressed all in white and wore garlands, as if for some ceremony. Then he heard their voices across the water. They were indeed performing a ceremony. It was meant to honor him and they were calling out their thanks for the good life, the wealth and the freedom to sail the seas which he had brought them.

Order and peace were the gifts Augustus gave to Rome in return for his power. When he had established them and built a government to protect them, they lasted for nearly two hundred years. Toward the end of his reign, Augustus sat down to write a history of his years as Rome’s ruler. Caesar would have been puzzled by it, for it was so short that it could all be engraved on two bronze tablets. In one of the last paragraphs, Augustus wrote: “While I was administering my thirteenth consulship, the senate and the knights and all the people gave me the title ‘Father of my Country.’ ” He was prouder of this title, the gift of his citizens, than of any he had won by victory in war or power in politics.

In A.D. 14, Augustus died. For nearly forty-five years he had been the pater familias of Rome. In every city of the Roman world, men and women went to their temples to pray. They prayed to many different gods — in Rome, to Jupiter; in Athens, to Zeus; in Alexandria, to Isis and Ra, but they they all made the same prayer: “Send us another Augustus so that we can live in peace.”