ROME was no longer just a city — it was a world. In the reign of Hadrian, the blaring trumpets that announced the comings and goings of the emperor echoed in Spain, Syria and Britain as often as in Italy. Hadrian wanted to know what was going on in all of his empire. He wanted to inspect the troops and forts that held the frontiers and to judge for himself the wisdom of the governors he had sent to rule the provinces. He wanted to visit the towns and cities, to see their ancient buildings, to plan new buildings where they were needed and to build new towns in the frontier provinces. He wanted to meet the people. They were citizens of Rome, even though their homes were hundreds of miles from Italy and they had never seen the Forum. Hadrian’s journey through the empire took eight years. He followed the Roman roads and the sea routes Rome had freed from pirates, until he had visited every part of the world of which he was the sole, all-powerful ruler.

He met many other travelers on the roads. Travel was easy now and safe. Rich Romans, imitating the emperor, had become eager tourists. They flocked to Greece; to them it was a quaint place out of another age. They studied its famous buildings, bought statues and pottery for souvenirs and paced out the old battlefields which they had read about in Plutarch’s histories. In Egypt, they went shopping in Alexandria, still handsome and a bustling center of trade. They rode in elegant comfort on sightseeing barges that took them up the Nile to Memphis and Thebes. There they admired the oldest buildings known to man and scratched their initials in the stonework.

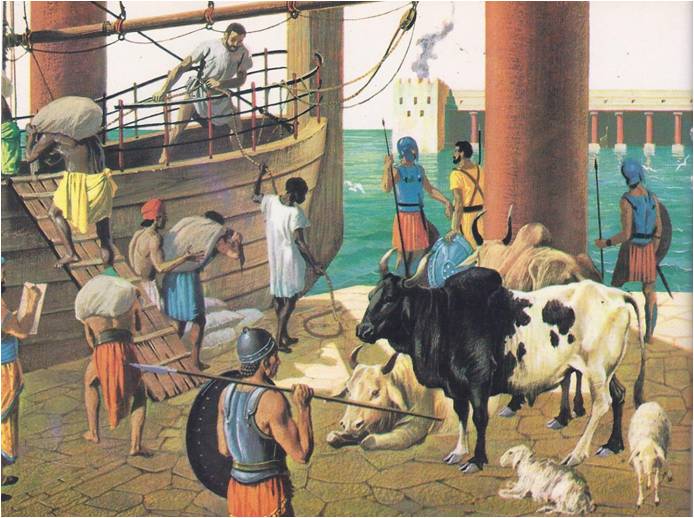

This eastern area was Rome’s “Old World.” It had charming but outdated Greek towns and bustling Alexandrian cities, where everyone spoke Greek. In the west, however, there was a modern land, a world that Rome had built. In Gaul and the German lands, in North Africa, in Spain and Britain, Hadrian looked with pride at new cities standing on the old barbaric hills. They were as fine as any cities in the east.

At Athens, Hadrian had gone to see for himself the buildings called the most beautiful in the world and he had agreed that they were splendid. Then he had come upon the foundations and a few lonely columns of the gigantic temple which an Athenian tyrant, Pisistratus, had begun six hundred years before. It was a project so impossibly big that no other ruler of Athens had tried to finish it. Hadrian looked it over, called for his own workmen and the temple was completed. It had taken a Greek to imagine it, but a Roman to build it.

That was the story in all of the empire. Romans looked for the jobs that needed doing and got them done. Unlike the Greeks, their scientists did not ask “Why?” They asked: “How?”-“How does it work?”-“How does it fit together?”-“How can we use it?” The Romans borrowed the Greek builders’ designs just as they borrowed the Greek teachers’ ideas, because they were good and they worked. It was constructing buildings, not designing them, that excited a Roman builder. His art was engineering.

No project was impossible for Roman engineers and the bigger, the better. They constructed theatres that could hold 80,000 people. They built mile after mile of line roads across deserts and mountains to the edges of the Roman world. Their bridges and aqueducts spanned rivers and gorges with arches of stone. The Etruscans had taught the first Romans the trick of building an archway of wedge-shaped stones fitted together so that they could not fall. In the seven or eight hundred years since then, their pupils had become master builders who used the arches to give strength to some of the biggest structures man had ever made. In Hadrian’s homeland, Spain, they had bridged the great Tagus Gorge. The largest of the bridge’s six arches was 90 feet wide and 150 feet tall. It was made of granite blocks, without mortar or braces to hold them in place. The two-storied aqueduct of Segovia, a stone canal to carry water from the mountains to the city, rested on 128 arches of uncemented stone. Two thousand years after it was built, the aqueduct was still being used. When the Romans discovered how to make concrete, there was no limit to what they could build. They set wide domes on their temples, instead of the old wooden roofs. In every corner of the empire, they built arches that were wider, taller and stronger than before. For centuries the arches would stand, a sign that the Romans had come that way.

HADRIAN’S TRAVELS

The new cities had that Roman stamp, too. Each was a little Rome, with its Forum, senate house, theater, library and well-paved streets. Men, whose barbarian fathers had lived in huts and fought in the wilderness, now lived in Roman houses, worshiped Roman gods in Roman temples and cheered the charioteers in Roman arenas.

Hadrian was more than a royal tourist in these western cities and he was no foreign overlord. He spoke to the people in the Latin they spoke. He shared their worries about trade or the crops. Wherever he went, people knew his face, because they saw it every time they went shopping or counted their money. Roman coins were marked with a portrait of the emperor. It was a handy way to put a reminder of him in every home in the empire. The inscriptions on the coins were carefully chosen to point out to the people the good things that this emperor was doing for them. “Hadrian, the generous giver of money to the poor,” they said, or, “Hadrian who built the temple of Roma and Venus.” Several times a year, the words were changed, so that the latest news of the emperor’s good works could be sent hurrying from hand to hand across the Roman world. When he traveled, new coins were issued announcing his arrival in the various provinces. For peaceful provinces, the inscriptions read, “Hadrian, the bringer of order and wealth.” For places where there was unrest or rebellion, the words .were “Hadrian, commander of great and powerful armies.” Year after year, there were coins that carried the Emperor’s favourite message, Hadrian, like Augustus, the father of his country.”

When Hadrian spoke to the people, he called them citizens and most of them now were. They shared the protection of his legions and the justice of Roman law. No angry governor could sentence them to torture or to death, for they had the right to “appeal to Caesar,” which meant a trial in Rome. Under Hadrian, the harsh laws of the old Rome — the city — had been changed to deal fairly with the people of the new Roman world.

From Antioch to London, Hadrian was the first citizen of that huge Rome. He was the leader of sixty-five to one hundred million people who were held together by their loyalty to one government, Hadrian’s government. In Hadriana, a town he founded in the East, a philosopher-poet wrote a song of praise about the city that became an empire: “To Rome’s rule we owe it that the wide world is our home, that we are all one people, citizens of Rome.” The Greek philosophers had imagined such a world, where all mankind was one. Alexander the Great had dreamed of shaping such a world by conquest. Again, it had taken a Roman to build it.

It took strong Roman walls to guard it. The Atlantic and the deserts of the Sahara protected Rome on two sides, but along the other frontiers there were barbarians and Asian kings. Ceaselessly they beat against the defenses, always hoping to find a weak place, to break through and to rob and plunder the rich lands on the other side. When Hadrian came to Britain, he saw the ravages made by savage Picts and Celts, who had made raids from Scotland. He ordered his soldiers to build a wall, a wall of concrete faced with stone, twenty feet high and eight feet thick, across the entire width of Britain. Hadrian himself paced out the line of the wall and planned the castles for the soldiers who would guard it. Then his troops built it, just as they built a wall of upright oak logs‚ nine feet high, that ran the 345 miles between the Rhine and Danube rivers on the German frontier.

Where there were no walls of stone or logs, there were walls of men. Rome’s legions numbered hundreds of thousands. Italians, Britons, Africans, Spaniards, Egyptians and Gauls fought side by side. They guarded the Roman world’s most treasured possession — the Pax Romana, the Peace of Rome. It gave order to the empire, brought wealth to its people and kept war outside its borders.

Rome had taken on an enormous and difficult job — to make a Roman city of the world, to put a wall around it and to rule it well. When Hadrian came home from his long journey, he thought that perhaps it could be done. The Romans had always taken on big jobs. They were men of action. They had been that way even years ago when, as the people of a little country town, they had tried to conquer all of Italy. Virgil had recognized this when he wrote his great poem for Augustus and expressed what it meant to be a Roman:

Other men, I know, will shape fine bronze

Into statues that seem to breathe, and carve from marble

Faces as real as life. Others will speak

With finer words than ours, or learn to chart

The map of the sky, the circling journeys of the planets

And where the stars will rise. But Roman, remember:

To rule the nations wisely with fair laws,

To bring them peace forever, to destroy the warlike

And treat the conquered kindly. These are our arts.