AS THE news of Caesar’s death spread through Rome, sorrow, anger and fear took hold of the city. On March 17, two days after the murder, the Senate met again. Cassius, Brutus and the other assassins took their usual places. There was no doubt that most of their fellow senators felt that they had done the right thing in ridding Rome of a tyrant, but Caesar’ s veterans were still in the city, taking their orders now from Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, who had been his Master of the Horse, the commander of the cavalry. Mark Antony was still consul, he had not yet said what he intended to do about Caesar’s murder, but certainly he would not forgive the killers.Of course, no one could tell what the mob might do. If the people took it into their heads to avenge the murder of their hero, there might be many more killings. So it was a cautious, quiet group of men who gathered in the Senate to discuss the death of Caesar and the future of Rome.

When Mark Antony spoke, he surprised them by not demanding that the assassins be arrested and put on trial. Perhaps he was afraid that they had strong forces of their own or that he might be the next victim. Whatever his reasons were, he offered to make a bargain. He would agree to let the assassins go unpunished, if the Senate would agree to approve Caesar’s will and allow his friends to give him a proper, public funeral. To the senators, the terms sounded fair — better, in fact, than they had hoped for. They quickly agreed to their part of the bargain, ended the meeting and went home, congratulating themselves that it all had been so easy.

THE FUNERAL OF CAESAR

On the day of the funeral‚ a restless crowd packed the Forum. Caesar’s body was carried into the square at the head of a great procession. The long columns of his soldiers filed past and the city officers and his friends, who had dressed themselves in the splendid purple gowns which he had worn in his parades of triumph. Carried high, so that everyone could see it, was an ivory couch on which was spread the robe which Caesar wore that last morning at the Senate house. The cloth was blood stained and marked with the twenty-three slashes made by the daggers of his killers.

When the procession stopped in the Forum, Mark Antony began to speak to the crowd about Caesar his friend. He read aloud from Caesar’s will. It said that his gardens along the River Tiber should be opened to the public as a park and that every Roman citizen should be given a sum of money from his fortune – 300 sesterces, about 15 dollars. A murmur of pleased surprise swept through the crowd, but it soon gave way to angry shouts of “Death to the murderers!” Antony spoke on, for he had more to say about Caesar’s generosity, but suddenly his speech was interrupted. Someone in the crowd threw a torch onto the couch on which the body lay. As the couch began to burn, more torches were thrown. A kind of madness, partly grief and partly wild excitement, seized the people in the Forum. Caesar’s friends tore off their purple robes and threw them into the flames. Women flung their jewelry and soldiers added their banners. Then a man took a branch from the fire, brandished it over his head and called for everyone who had loved Caesar to follow him to the houses of the murderers. The fury of the crowd broke loose. They poured from the Forum into the streets, shouting and waving torches. Behind them, Mark Antony stood silently smiling, while the flames of the funeral pyre flickered and blazed higher.

Caesar’s veterans still guarded the peace of Rome, so the assassins’ homes were not burned. The soldiers had no commander in chief and Rome was without a ruler. The days that followed the funeral brought confusion and civil war, while the Romans struggled to find a man or a government that could bring order to the world which they had conquered.

Cassius and Brutus said that they had killed Caesar to save the Republic, but the Republic had long been dead. It had been killed by Sulla and Marius and the senators who were greedy and the people who could only be trusted when a man with an army told them what to do. The senators tried to take control of the state, but Mark Antony had already turned their old enemy, the mob, against them and their new leaders. Soon Cassius and Brutus had to flee from the city, leaving Cicero to guide the Senate with his artfully made speeches. Cicero knew politics in Rome too well to believe that fine words in the Senate could control the Romans. He knew that the Senate needed a champion to fight for it, another Sulla or another Pompey, if it was ever to have its way again. Like Caesar’s soldiers and all of Rome, he waited for the new commander to appear.

OCTAVIUS COMES TO ROME

Mark Antony, of course, hoped to be the new Caesar. His speech at the funeral and the riot it stirred up, had been carefully planned as the first step in his campaign. In the will, which he had shown so openly to the crowd in the Forum, Caesar himself had named an heir. He had not chosen Mark Antony. Instead, he had given his titles, his fortune and his place in Rome to his nephew, Caesar Octavius.

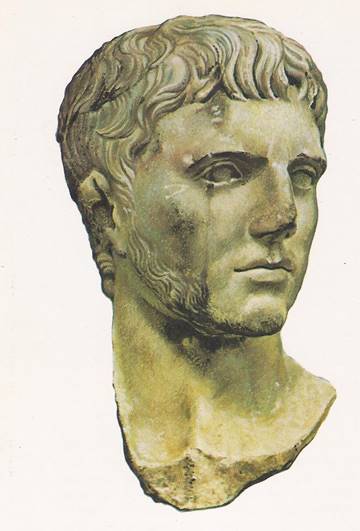

Octavius was just eighteen, a student in Greece. Antony and other men in Rome sent him messages urging him to stay away from the city. His life would be in danger, they said and there was little he could do in Rome without Caesar to protect him. Octavius decided that he might be able to do a great deal more than they expected. If he was Caesar’s heir, then he would act like Caesar. He ignored the warnings and rushed to Rome to claim what was rightfully his.

Mark Antony tried to greet Octavius as though he was glad to see him, but he found it hard to do. The young man seemed too much like a rival. He was handsome. He had his uncle’s talent for charming the people. Like Caesar, he dealt ruthlessly with anyone who got in his way. When Antony came to greet him, Octavius was polite but cold. He was angered by Antony‘s attempts to talk to him like a jolly older brother, and was not frightened by Antony’s threats. He reminded Antony sharply that he, Caesar Octavius‚ was Caesar’s only heir and he did not mean to share his inheritance.

Antony left him alone then. He was annoyed that the young man was so stubborn, but he was not greatly worried. After all, he thought, Octavius was little more than a child, with no army and no powerful friends in Rome. He might be a bother, but nothing more.

Cicero, the crafty leader of the Senate, had other ideas. He knew as much as any man could about the strange turnings and sudden shifts of power in Rome. From his place in the Senate house, he had watched the champions come and go. He had seen the strong ones honored and the weak ones crushed and forgotten. Always, he himself came through safely, like a skillfully steered ship riding out a storm. He had grown up in Sulla’s Senate and helped to snub Pompey when he came home from Asia. The Three-headed Monster had chased him out of Rome for a year or two, but in time the partners had invited him to come back. He had helped to persuade Pompey to fight for the Senate, yet Caesar had treated him with honor and asked his help in dealing with the politicians. When Cicero thought of his long, successful career, he had every reason to be proud and pleased with himself. He had had many years of power, simply because he was clever. He had not joined the plot against Caesar; murder was not his way to solve a problem. Now that Caesar was dead, he was eagerly looking for a way to turn the turmoil in Rome into a victory for himself and the Senate. In the young Octavius‚ he saw a champion who seemed to fit into his scheme perfectly.

OCTAVIUS AND ANTONY

At first, Cicero said nothing. Meanwhile, he kept a sharp eye on Octavius. He was pleased to see how neatly the boy went about winning the mob to his side. Octavius discovered that Antony, the “guardian” of Caesar’s fortune, had spent the money that was supposed to go to the people. When Antony refused to pay it back, Octavius began to sell his own possessions and to borrow in order to raise the money. Of course, when the gold was handed out, he made certain that every-one knew exactly what had happened. The stories of his generosity and honesty spread to the soldiers, the armies which gave Antony his power. Quietly the legions began to offer their services to Octavius and Cicero decided that it was time for him to act. He went to Octavius and asked him to become the defender of Rome against Antony. He said that Octavius, with his popularity and the support of the soldiers, could easily take control of the city. Cicero promised that the Senate would make it legal.

Then, when Octavius had raised an army and Rome was again safe for the Senate, Cicero had no more use for him. “The young man is to be honored, to be praised and to be pushed aside,” he said. Once again the Senate would rule Rome.

With these words, Cicero condemned himself to death. For the young man would not be pushed aside. He marched his army against Rome instead of Antony. When he had captured the city, the people elected him consul. The election made Octavius the master of Rome and Italy. The provinces, however, were held by his rivals and enemies. Antony and Lepidus had taken the West. In the East, Brutus and Cassius had built a mammoth army. Octavius could not take on all of them at once. So he did what his uncle Caesar would have done: he invited his rivals to be his partners in a war against his enemies. He had no trouble persuading Antony and Lepidus to join him. In 42 B.C., the three of them were elected “Triumvirs of Rome,” whose duty it was to hunt down and destroy the murderers of Caesar.

At Philippi, in Macedonia, Octavius and Antony each fought and won a battle against the armies of the assassins. Brutus and Cassius killed themselves to avoid capture. In Rome, Cicero was condemned and executed. Once again, the Roman world was in the hands of three greedy partners.

The Second Triumvirate was no secret, of course. It was the legal government of Rome, but it worked no better than the old partnership of Caesar, Crassus and Pompey. Lepidus was weak. Antony and Octavius were rivals. When Antony went to campaign in Asia, he left his secret agents behind to stir up trouble in Italy, where Octavius was in charge. Octavius, in turn, cut off Antony’s supply of men and equipment. The East was Antony’s downfall, for it was there that he met Cleopatra, whose beauty had kept Caesar in Egypt for more than a year.

Cleopatra still dreamed of a Roman conqueror who could make her the Queen of the East or even of the Mediterranean. Caesar, her first choice, was dead. She had considered Pompey’s son but he did not have enough power. Antony was a genuine conqueror with a strong army and Cleopatra had heard that he had a weakness for beautiful women.

ANTONY AND CLEOPATRA

When he came to the East, soon after his victory at Philippi, Antony invited Cleopatra to visit him. The invitation was a matter of courtesy, for Egypt was an independent kingdom — Caesar had not insulted the queen by making her country a province. Cleopatra was delighted to have a chance to meet the great new general, but she did not answer his polite letter. She meant her arrival to be a surprise, one that she hoped he would not soon forget. Years later, the world still remembered every detail of what turned out to be one of the most important meetings in history. Plutarch, the famous Roman historian, heard about it from his grandfather, who had talked to a man who said he had been on the scene. Plutarch described it this way:

Cleopatra came sailing up the river in a barge with a gilded bull and outspread sails of purple, while oars of silver beat time to the music of flutes and fifes and harps. She herself lay under a canopy of gold, dressed like Venus and beautiful children, like painted Cupids, stood on each side to fan her. Her maids were dressed as sea nymphs. Some of them stood steering at the rudder and others worked the sail-ropes while the sweet scent of perfumes drifted from the boat to the shore.

Antony, the conqueror, was quickly conquered. Before long, he lost his interest in campaigning and hurried off to Alexandria and Cleopatra. He was like a schoolboy on vacation; he had no time for anything but pleasure. Cleopatra was always at his side. She feasted with him, went hunting with him, and learned to play at dice with him like a soldier. When he exercised his horse or practiced swordsmanship, she was there to watch. In the evenings, they rambled about Alexandria, dressed like beggars, bursting into the houses of astounded commoners or playing tricks on their own courtiers.

Like all vacations, Antony’s vacation came to an end. New wars broke out in Asia and when Antony asked for troops from Rome, Octavius did not send them. Antony rushed home. A conference of the triumvirs was called and like the earlier partners, the three generals agreed to split the world among themselves. Octavius was to have Italy and the West, Antony was to have the East and Lepidus was to have Africa, the thinnest slice of the pie. Again, a marriage sealed the bargain. When Antony returned to the East, he had a wife, Octavia, the sister o£ Octavius. For two years Antony ruled Rome’s eastern provinces from Athens, with Octavia at his side. Then troubling reports began to come to Rome. Octavius had taken over Lepidus’ legions, thus doubling his power to twenty-two legions. He was master of the West and his successes were the talk of Rome.

Although Octavia did her best to keep peace between her husband and her brother, Antony insisted that he must do something to add to his reputation before the Romans forgot about him. He hurried to Asia to fight barbarians and he hoped to win land and treasure. The campaign did not go well. Although Antony lost no battles, he won no great victories, and many of his men were killed. Weary and discouraged, he went again to Egypt where life was pleasant. This time he stayed. When Octavia wrote to ask if she should come to Alexandria; he told her to go back home to Rome.

Cleopatra was full of plans for Antony and herself. Soon both of them were talking about the world which they would rule together. They were married, despite Octavia, who still waited in Italy. Then Cleopatra crowned Antony as her king and she spoke as though their kingdom would include a number of cities which belonged to the Romans. When the news reached Italy, Octavius ended the partnership and the Senate declared Antony the enemy of Rome.

THE BATTLE OF ACTIUM

In 31 B.C., the forces of the two partners met in a great sea battle near Actium in Greece. The sides were almost even; each commander had come with 500 warships and more than 40,000 legionaries. Antony’s crews, Romans who found themselves fighting for Egypt, had been told wild, frightening tales about Cleopatra’s ambition to rule the East. They had seen for themselves the strange ways of the Egyptians, and they half believed that Antony had been bewitched. When the battle began, many of them refused to fight. Cleopatra and her squadron were forced to break through a line of Octavius’ battleships to avoid being captured. Antony, too, had to run from the fight, leaving most of his fleet to surrender or be taken.

In the morning, before the battle, Octavius had prayed to Apollo, promising to build him a new temple if he helped Rome to win a Victory. By afternoon, Octavius knew that it would have to be a fine temple, for the Victory was his, his losses were small and his enemies had been badly beaten.

Antony and Cleopatra fled to Alexandria. In the summer of 30 B.C., Octavius marched his armies around the Aegean, through Asia Minor and into Egypt. Antony tried to hold them off, but his men deserted as soon as the Roman standards came into sight. Then someone told him that Cleopatra was dead. He left the battlefield, found a quiet place and killed himself.

The story of Cleopatra’s death was false, however. She was alive, waiting in Alexandria for Antony — or perhaps Octavius. When the city was taken, she was made a captive in her own splendid palace. Octavius, the new Caesar, came once to visit her, but her charms did not seem to affect him. Then she learned that he planned to take her to Rome in chains, like any-other prisoner of war. She called for her priests to bring her an asp, a poisonous snake that was sacred to her goddess Isis. She said farewell to her maids, let the asp bite her and in a moment she was dead.

Now Egypt belonged to Octavius and so did all the Roman world. It was a tired, confused world, longing for peace. For too many years it had been the battlefield on which Romans slaughtered other Romans.

The new master of Rome was thirty-two years old. Perhaps it was good that he was young, because making peace would be much more difficult than making war had been and it would take time.