Within 150 years of the death of Hammurabi, the cities of Mesopotamia were powerless and other peoples took up the struggle for the Near Eastern world. Among them were the Hittites, who had taken the city of Babylon. The rough Hittite tribesman hardly knew what to do with such a splendid city, let alone with an empire, so they went back to their strongholds in the highland plains of central Turkey. They had been living there for several centuries, ever since they had left their homeland in the steppes of central Asia.

When the Hittites first moved into Turkey, they had found a land of peasants and small city-states unable to unite in resistance. The Hittites allowed the people to keep their own gods and languages, recruited officials to manage affairs and left the farmers and craftsmen to their work. It was a bleak, rocky land, hot and dry in summer, cold and windswept in winter but, there were grains and cattle and the people made beer and wine and kept bees for honey. The land was rich in metal ores, too. Later the Hittites were among the first to use iron.

The Hittites set themselves over the native peoples as an aristocratic warrior class. For many years, rival Hittite tribes and chieftains fought among themselves before Labarnas established himself as the first true king. He led the Hittites in expanding their power throughout Turkey and his son Hattusilis I, extended it to Syria.

Hattusilis made the city of Hattusas his capital. It was strategically located near the crossroads of the main trade routes in central Turkey. As his reign neared its end, Hattusilis could take pride in the kingdom he was leaving to his people, but he had one unpleasant task to perform. He had raised his nephew as his heir and the boy had proved to be ungrateful. In anger and sorrow, the aged Hattusilis wrote in his will: I, the king, called him my son, embraced him, exalted him and cared for him continually. He showed himself a youth not fit to be seen. He shed no tears, he showed no pity, he was cold and heartless. Hattusilis then names his grandson Mursilis as his successor.

It was Mursilis who led the raid on Babylon. When he returned to Hattusas, he was assassinated and once again, various Hittite families and chieftains fought amongst themselves for the throne. Gradually, however, laws were set down and order was restored. The laws of the Hittities, in fact, were among the best of their time. They called for strict punishment, but it was not always the “eye for an eye” of the Babylonians.

The Hittities Triumph

All this time the Hittities were barely able to keep from being wiped out by neighbouring tribes. The greatest threat came from the kingdom of Mitanni in the southeast. The Hittities, however, remained independent and from the Mitanni enemies they even learned about trained horses and chariots. The Hittities soon became masters at using the horse-drawn chariot in battle and regained much of their former territory.

Under Suppiluliumas I, who became king about 1375 B. C., the Hittities reached the height of their power. He strengthened the Hittite kingdom within Turkey, defeated the Mitanni kingdom and took over most of Syria. He called himself “the great king. King of the Hittite Land, the hero, the favourite of the Weathergod.” His people did indeed look upon him as a hero and foreign rulers respected him as much for his diplomacy as for his conquests. The widow of an Egyptian Pharaoh even proposed to marry one of his sons.

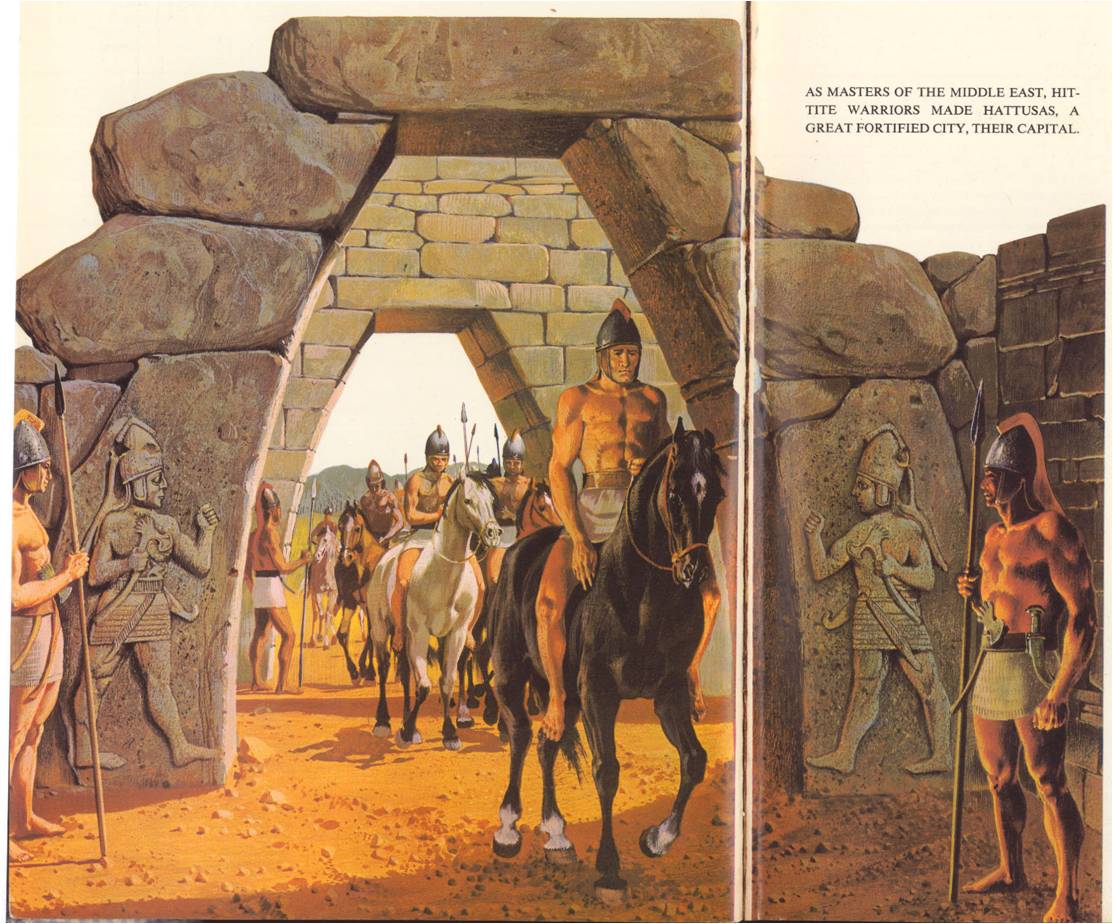

Hattusas, the capital, was now a great fortified city. It was enclosed by massive walls, some four miles around, with towers and tunnels. Carved sphinxes and lions guarded the gateways and within the city were temples with dozens of storerooms. In the royal library were thousand of clay tablets recording all the administrative and diplomatic affairs, the laws, literature, history, correspondence and royal proclamations.

In the hills outside Hattusas was the sacred area of Yazilikaya, with its ceremonial buildings leading into the sanctuary beneath the cliffs. Carved on the rocks were figures of gods and men. During religious festivals, the king led the procession up to Yazilikaya, for he was high priest as well as supreme ruler. He spent part of each year travelling about his kingdom to preside over various religious ceremonies. The Hittities had hundreds of gods involved in every part of their lives. Chief among them was an old Hittite god, the Weathergod, but the Hittites had adopted many of the gods of the peoples they had come in contact with. The Hittites were a practical people who never hesitated to borrow anything from their subjects or neighbours. They were especially influenced by the peoples of Mesopotamia in law, religion, art, medicine and astrology and even took over the story of Gilgamesh.

They borrowed words freely, too, although they had their own language, an early version of the languages later to be spoken throughout much of the West. The Hittities developed their own picture-writing, somewhat like Egyptian hieroglyphs, but this was used mainly for inscriptions carved on monuments. For business and diplomacy they took over the cuneiform script of Mesopotamia, using the wedge-shaped signs to write in their own language on clay tablets. In their dealings with foreign peoples, Hittities often used Akkadian, the old Semitic language of Mesopotamia.

Treaty with the Egyptians

The successors of Suppiluliumas I fought to hold his empire, but during the reign of his grandson Muwatallis a new threat appeared. The Egyptians under the Ramses II decided to force the Hittites out of Syria. In 1286 B. C., the two great powers met at Kadesh, in northern Syria. Each army numbered about 20,000 men and was led by its king. The Egyptians later charged that Muwatallis had tricked them with two Hittites who pretended to be deserters and said the Hittites had retreated. This put the Egyptians off guard and the Hittite chariots, in a series of maneuvers, swept down on the Egyptian infantry. Even when a horse was speared, the falling horse and chariot crushed the Egyptian soldiers.

The Hittites won the first battle, but the soldiers stopped to plunder the enemy camp and the Egyptians were able to counterattack. Later, the Egyptians carved the story of the battle of Kadesh on monuments and claimed total victory. The truth was that the Hittites not only stopped the Egyptians but went on to win more territory in Syria.

Finally, the Hittites and Egyptians came to respect each other’s strength and in 1269 B. C., they made a treaty. They agreed not to attack each other and to come to each other’s defense. It was the most important event in international affairs. The treaty was engraved on a silver plaque, the Egyptians carved its text on walls and the Hittites copied it in cuneiform on tablets for the royal library. Later the Pharaoh Ramesses II, married a Hittite princess and for many years there was a peace in the Near East.

Meanwhile, there were new forces stirring in the west; the peoples of eastern Europe and the Mediterranean were on the move. Among them were the Phrygians, who swept across Turkey. About 1200 B. C. the Hittite capital, Hattusas, was destroyed and other cities were wiped out. Some Hittites migrated south to their Syrian cities, but the Hittites were no longer a power.

For several centuries afterwards, Syrian city states such as Carchemish and Karatepe kept up some of the Hittite culture, using Hittite picture-writing on their monumental carvings. Like the older Hittites, they borrowed from many other peoples, including the Egyptians, the Mesopotamians and the Phoenicians, but they lacked the energy of their ancestors. By 700 B. C., these Syrians city-states were all taken over by the Assyrians.