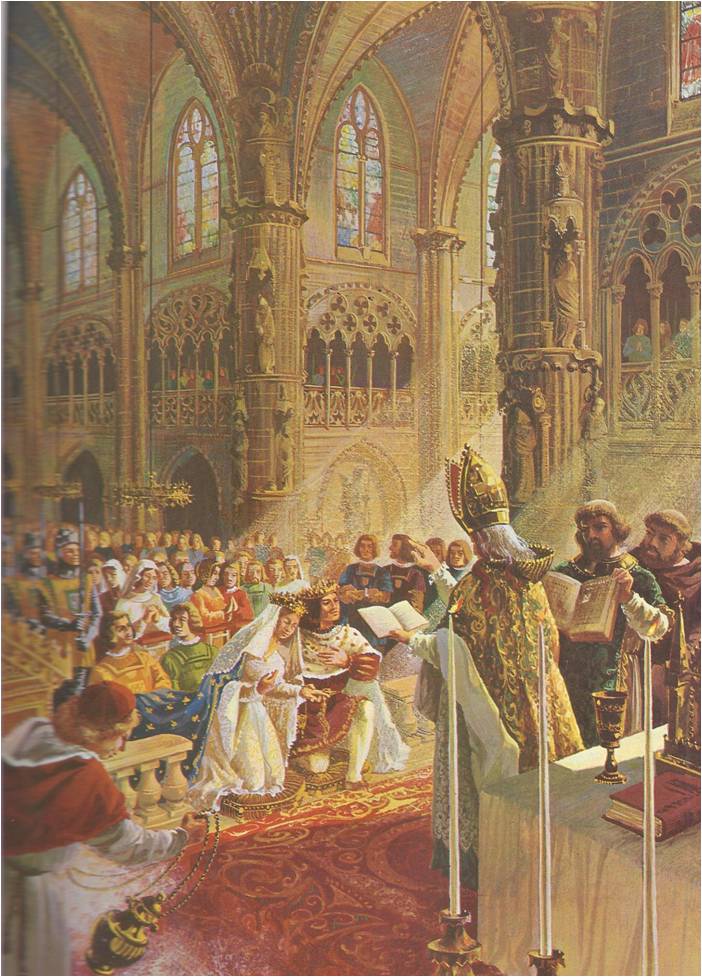

IT WAS Wednesday, October 18, 1469 and Princess Isabella of Castile and Prince Ferdinand of Aragon were being married. At the end of the beautiful ceremony, the two thousand guests cheered and the entire city of Valladolid began a week of celebration.

Isabella was overjoyed, for she loved her husband and he loved her. They seemed well matched. Isabella was eighteen, tall, blonde and blue-eyed – “The handsomest lady I ever beheld‚” one nobleman said. Ferdinand was slightly shorter than his wife, but he was handsome. Isabella was intelligent, very religious and strong-willed. Ferdinand, too, was intelligent and he was extremely shrewd. The happy couple talked for long hours, went riding, played chess and their love grew.

Isabella was glad to escape from the royal court of her brother, King Henry IV of Castile. Castile was the largest of the several kingdoms that made up Spain and under Henry IV it was probably the worst ruled. Isabella hated Henry’s court. The nobles were proud, ignorant and insolent; some were fierce warriors, the rest seemed lazy. Most of them taxed their peasants harshly, then spent the money on magnificent lace-trimmed clothes, on drinking and fighting. King Henry himself set a bad example. He was cruel, he loved to watch spectacles and fires, he let his guard of wild Moorish soldiers insult the young Spanish ladies. When their fathers complained, he told them they were insane and had them whipped in public. The nobles could get anything they wanted from Henry. Sometimes he gave them blank checks to take any sum they wished from Castile’s treasury. Henry was a weak king and became known as Henry the impotent.

In the provinces, the nobles were even more unruly. Around Seville, the Duke of Medina-Sidonia and the hot-headed Marquis of Cadiz were at war, each leading several thousand infantrymen and armoured horsemen. They were raiding each other’s territory, ruining the countryside and seizing hundreds of villages. When he was finished with the Marquis, Medina-Sidonia made war on two other noblemen. His conduct was not unusual. All the nobles fought regularly for glory, wealth and the love of fighting.

There were still others who disturbed the peace. Robber-bands prowled the countryside and the cities were not much safer. The warring nobles stirred up feuds among the common people, between the Old Christians and the New Converts, who had once been Jews. Such a feud broke out in Segovia in May, 1474. The Old Christians and some soldiers plunged through the city, burning, pillaging and slaying New Converts. When Ferdinand and Isabella rode into Segovia in the autumn, blood still stained the streets and walls. They were more disgusted than ever with the disorder. Then, in December, came the news that King Henry had died of kidney and liver trouble. He had left no children and Isabella would be queen of Castile.

Isabella’s coronation was held high on a platform in the main plaza of Segovia. She was dressed all in white and the gold crown was placed on her head by the Archbishop of Toledo, who was clothed in gold and purple and shining armour. Cannons roared, bells rang out and the crowds chanted, “Long live the Queen!”

The king of Portugal, Alfonso V, wanted the throne of Castile for himself and he thought he had a way to get it. His sister Juana had been married to the dead King Henry and Juana had a daughter whom Henry had refused to claim as his own. Now Alfonso pretended the girl was indeed Henry’s daughter. He gathered a strong army and invaded Castile; he married Juana’s daughter, his own niece and he claimed the throne of Castile. Many Castilian nobles supported him.

Isabella had no army and little money, for Henry had left behind him confusion and debts. She rode through all Castile, appealing to the people for help. At the same time, Ferdinand brought in volunteers from Old Castile, Biscay and Asturias. Many of them were peasant boys and some were criminals, for Ferdinand freed any prisoner willing to fight for him. When the army was trained, Ferdinand led it against Alfonso in his stronghold near Zamora.

In March, 1475, the two armies met. The Portuguese crashed into the Castilian line and six squadrons of Ferdinand’s cavalry fled in disorder‚ but most of the Castilians held and the battle raged for hours under a chill rain. It was dusk when the cardinal of Spain, fighting like a tiger, seized the Portuguese flag. The Portuguese line began to waver and fat King Alfonso, sweating and puffing, fell back. Their courage revived, Ferdinand’s six cavalry squadrons charged. The Portuguese retreated through the mud with the Castilians in pursuit. Some Portuguese soldiers jumped into the Duoro River to escape the Castilian swords, but the current pulled them far out and in their heavy armour they sank and were drowned. Alfonso fled and his dream of ruling Castile was at an end.

Isabella and Ferdinand were now unopposed in Castile. Their power seemed strengthened in 1479 when Ferdinand became king of the second largest Spanish country, Aragon. Aragon included the great city of Barcelona and Aragon owned an empire that controlled part of Italy, Sicily and Sardinia. However, the nobles of Aragon had passed laws making their king even weaker than Henry the Impotent had been. Ferdinand found his coronation almost humiliating. He had to kneel at the feet of the Justicia Mayor, a hereditary official whose power over trials and sentences was perhaps greater than the king’s. The Justicia Mayor read the customary words that put the king in his place: “We who are as good as you . . . accept you as our king . . . provided you accept all our privileges, liberties and laws, but if not, not.” Ferdinand could do little in Aragon to weaken the nobles, but in Castile he and Isabella had more success.

Isabella’s haughty spirit set the tone for change. One day she heard Ferdinand’a uncle exclaim after a chess game. “I have beaten my nephew.” Coldly Isabella told him, “The king has no relatives . . . only servants and vassals.” She and Ferdinand succeeded in making the proudest nobles of Castile, the grandees, into servants and vassals of the state. They refused to let the grandees build fortified castles and made it difficult for the great nobles to raise armies to conduct private wars. Isabella made Ferdinand, rather than any grandee, the head of the great military orders of Santiago, Calabrava and Alcantara.

Even at the capital, Madrid, the grandees’ influence was limited. Isabella replaced many of them on the royal council with lesser nobles, called hidalgos. She taxed the grandees and made them pour back into the treasury the wealth that they had drained from it in Henry’s time. She took their playboy sons from their drinking and gambling and put them to studying under famous scholars. They learned poetry, astronomy and physics, until it was said that “no Spaniard was counted noble who held science in indifference.”

SPANIARDS AND MOORS

Ferdinand and Isabella sent royal officials, called corregidores, to govern the lawless cities and establish order. In the countryside, a strong court punished criminals so severely that the robber-bands began to disappear.

Then Ferdinand and Isabella turned their eyes south to Granada, the land of the Moors. War between the Christian Spaniards and the Moslem Arabs was centuries old. It began when the Arabs, who were called Moors by the Spaniards, crossed over from Africa and captured most of Spain. The Moors brought with them a new civilization; they skillfully practiced astronomy, medicine, mathematics and they built beautiful Moslem mosques with high rounded domes. The Moors nearly succeeded in conquering the rest of Spain, but the Christian kings, from their refuge in the northern mountains, fought back. Foot by foot, at great cost of blood and money, the kings won back all of Spain except Granada. Now the warlike Moorish leader, Mulay Hassan, planned to repair the Moors’ loss.

A CHRISTIAN KINGDOM

On the night after Christmas in 1482, Mulay Hassan led a band across the border. With rope ladders they scaled the mountain walls leading to the Christian town of Zahara. Catching the town unguarded, they drew their swords and rushed into the houses. Only then did the townsmen wake and scream in terror, “The Moor! The Moor!” Mulay Hassan’s men killed many persons and drove the rest back to Granada, to be sold as slaves.

Mulay Hassan’s raid spurred Ferdinand and Isabella to lead a crusade against the Moors. They gathered arms, skilled soldiers and consulted the nation’s greatest expert on forts, Ponce de Leön. They threw a great army against Granada, but the Moors fought back fiercely and trapped a sleeping Spanish army in a narrow valley near Malaga. The greatest Christian nobles of southern Spain were killed.

The Moors fought each other just as fiercely as they fought the Christians and this helped bring about their downfall. One day when Mulay Hassan was out on a raid, the people of Granada locked the gates of his city against him. They made Boabdil, Mulay Hassan’s son by his first wife, their new king. Mulay Hassan failed to recapture the disloyal city, but be held the rest of Granada and with the aid of his brother Al Zagal, the Brave Eagle, he continued to fight Ferdinand and Isabella’s army.

Boabdil also fought the Christians and on a foggy night in 1484 he was captured by the Spanish. Ferdinand had a clever idea. He proclaimed Boabdil king of Granada, made him promise loyalty to the Christians and then released him, but be held Boabdil’s son as a hostage. “Woe the day I was born,” said Boabdil, “for sorrow do I bring to my son” As Ferdinand had hoped, the struggle between Boabdil and Mulay Hassan weakened the Moors. With a new kind of heavy artillery, the Spanish demolished the Moorish forts. Ferdinand’s army conquered Murcia and stormed the stronghold of Baza. To maintain the siege, Isabella pawned her gold and silver plate, her diamonds and other jewels and in 1489 Baza fell.

The following year, Ferdinand marched into western Granada. With 10,000 cavalry and 40,000 foot soldiers, he laid siege to the Moors’ capital, the city of Granada. Still the Moors defied him, killing many Christians in skirmishes outside the city. By the winter of 1491, Boabdil’s people were starving and his government was collapsing. He surrendered in January of 1492. Ferdinand led a solemn procession to the Hill of Martyrs, while his royal chaplains chanted prayers of gratitude. Boabdil handed the keys of the city to Ferdinand, saying. “These keys are the last relics of the Arabian kingdom in Spain. . . . Such is the will of God.” Spain was now a Christian kingdom.

THE SPANISH INQUISITION

In this Christian kingdom there were millions of people who were not Christians — the Moors and the Jews. Isabella and Ferdinand believed that Spain could not really be a nation if it had more than one religion. This belief was common at the time, but nowhere was it stronger than in Spain, where Christians had battled Moslems for so long. Ferdinand and Isabella expelled all Jews who refused to become Christian. They sent to Granada a brilliant leader of the Christian church, Cardinal Jiménez, who forced the Moors to convert to Christianity. Even so, the rulers feared that the New Christians practiced their old religious in secret. They suspected that there were millions of disloyal Christian converts scattered through Spain. Before they had completely conquered Granada, the two rulers revived an old system of checking on the faith of Spaniards — the dreaded Inquisition.

Ferdinand and Isabella placed the Inquisition under their own command. It added to their power, bringing them money, information and greater control of their subjects. People were encouraged to report anyone suspected of being a witch, an atheist, a Moslem or a Jew. If the accused person doubted the tales of magical Christian escapes from Arab slavery, or did not eat pork, he was almost certainly considered guilty.

The agents of the Inquisition carefully watched a suspected heretic until he was alone, then arrested him and placed him in a secret prison. His family and friends were not told of his fate. In prison he was kept in chains. Often he was thrown into a solitary cell that was dark, dirty and overrun with rats and vermin.

The Inquisitors followed rules which they meant to be fair. They allowed the accused to name persons who might have informed on him dishonestly, out of spite. They sometimes even released women who claimed to be witches and said they had danced naked with goats, down into chimneys and strangled babies. The Inquisitors thought such women must be mad.

Some of the Inquisitors were fanatically religious and others were greedy. They were tempted by the chance of seizing the wealth of those they judged guilty. Frequently they had the accused person tortured to make him confess. If found guilty, he was sentenced in an elaborate public ceremony, an auto da fé, which imitated the doom of Judgment Day. A mild punishment might be a whipping. The prisoners were stripped to the waist. They were mounted on asses and a torture device, an iron fork, was locked on them to Stretch their necks. Then they were led through the streets and whipped, while the crowds threw rocks and dirt at them. The Inquisitors decided that some heretics were beyond reform and these were burned at the stake. Less serious cases were sent to the galleys or had their houses and goods seized. Ferdinand was generous and he sometimes returned some property, but even he and Isabella thought it only just for the Christians to take the lands and goods of non-believers.

COLUMBUS AND THE NEW WORLD

Ferdinand and Isabella considered raising funds for a Christian crusade against the Arabs of Africa. Instead, they gave their money to an Italian named Christopher Columbus. Ferdinand was sometimes annoyed by Columbus, who demanded important titles before he had accomplished anything. Nevertheless, Ferdinand and Isabella outfitted him with three ships. Like other educated people, they believed that the world was round and that Columbus would find the riches of the East by sailing west around the globe. In May, 1493, Columbus returned to Spain. He claimed he had reached Asia and as proof he brought with him six “Indians”.

Columbus had, of course, discovered a new world. It became known as America and soon Balboa, Cortés, Pizarro, Ponce de Leon and other Spanish adventurers, explorers, priests and soldiers were sailing to its shores. Spaniards conquered and plundered ancient Aztec and Inca civilizations and they began to build a new civilization in the Americas. The gold and silver they found in the New World helped make Spain the mightiest power in Europe for over a century.

Isabella died in 1504, leaving to Ferdinand her jewels and the hope of reunion in heaven. The last years of Ferdinand’s rule were troubled. For a brief time his daughter Juana and her husband, Philip of Burgundy, ruled Castile. But Philip died and Juan went mad and was imprisoned in the castle of Tordesillas. Ferdinand ruled again and struggled to keep the Castilian nobles from increasing their power. He performed one last great act. He made an alliance with England against France and while England attacked the Breton coast, Ferdinand marched his army into Navarre and wrested it from French rule and so, in 1512, all of Spain was finally united under one king. Four years later Ferdinand died, joining Isabella in the lasting memory of the Spanish nation.

CHARLES DEFEATS THE REBELS

In 1517, Ferdinand and Isabella’s 17-year-old grandson, Charles of Ghent, landed on the northerly coast of Asturias. Charles’ mother, mad Queen Juana, remained locked in the castle of Tordesillas and Charles was the new king of Spain. To many he did not seem very kingly. His jaw was so large that he could not speak properly. He loved to eat and although he complained about the Spanish food, he ate great heaps of fish, oranges, olives — food of any kind. Soon he grew very fat and ill with gout.

Charles spoke hardly a word of Spanish. From the Netherlands, where he had grown up, he

brought many gay Flemish nobles and he gave them important posts in Spain. Soon after his coronation Charles left Spain again to seek the throne of the Holy Roman Empire. He made Adrian, his old Flemish tutor, regent in his absence. The proud nobles boiled with anger and the townsmen, too, were outraged. By 1520 a number of Castilian cities were in revolt, fighting to win back all the independence that Ferdinand and Isabella had taken from them.

In August of 1520, the royal army marched to Medina del Campo to take the heavy artillery from the royal storehouse there. They planned to batter down the walls of Segovia and other towns that were in revolt. The citizens of Medina del Campo locked the gates against them. The angry soldiers set fire to the city and Medina del Campo, Spain’s great centre of trade, went up in flames. Its wools, silks, laces, furniture and art treasures, were all burned to ashes.

Everywhere in Spain merchants, artisans and even peasants were angry. The revolt spread through Toledo, Zamora, Salamanca, Guadalajara and other centres. The rebels stormed Tordesillas and secured the support of mad Queen Juana. With her approval they formed a council, or junta, which met as a parliament in the royal palace. The junta declared the regent Adrian deposed and attempted to rule Spain itself; the strong Spanish kingship seemed about to dissolve.

Charles learned from his mistakes. From Germany he appointed two grandees as co-rulers with Adrian. He let it be known that he was learning Spanish and he claimed that he truly loved Spain. The rebels meantime made some serious blunders. In their councils, labourers and even criminals gained a voice. Hating the nobles‚ the junta demanded that Charles let them take much of the nobles’ land and end a number of aristocratic privileges. The disgusted nobles began to turn to the royalist side. Throughout the winter of 152l the rival armies fought from Toledo to Villapando and the revolutionary forces grew thinner and weaker. In April the royalists pursued the remains of the revolutionary army to the village of Villahar. There, in a driving rain, the desperate rebels made a stand. The royalists quickly scattered them and tracked them down in barns and alleys. The next morning they hung the rebel leaders in the village square.

Charles returned to Spain in July, parading at the head of 4,000 German soldiers. In November an ambassador wrote. “His majesty is hard at work … those who were most guilty are being condemned every day.” Charles was merciful to some of the rebels. From this time on, both townsmen and nobles supported most of his policies and Spain remained a united kingdom.

HOLY ROMAN EMPEROR

Spain was not Charles’ only concern. In 1519 he won the throne of the Holy Roman Empire, which made him Emperor Charles V, overlord of Germany. He also ruled Austria, the Netherlands, southern Italy and Spain’s overseas empire — most of North and South America. Like his Spanish ancestors, Charles insisted that all his huge empire follow one religion, the Catholic faith. The rulers of Europe had long thought that allowing more than one religion would split a kingdom and bring disaster to the king, but things were changing. In Wittenberg, a young friar, Martin Luther, had proclaimed a reformed religion, Protestantism and many Germans adopted his faith. The Turks, believers in the Moslem faith, were storming across east Europe, conquering Slavs, Greeks, Byzantines, Bulgars and the other Christians there. Charles despised both the Protestants and the Turks. He used Spanish arms and gold to fight the enemies of Catholicism and to protect his great empire. Under his rule, Spanish soldiers fought war after war.

One of Charles’ enemies was France. The French ruler, Francis I, was a Catholic king, but he was also an ambitious one. Francis greatly admired the art and culture of Renaissance Italy and above all he wanted to replace Spanish influence in Italy with French power. In addition, Francis claimed Spain’s province of Navarre.

Charles fought the French almost continually. In Navarre in 1521, near the village of Esquiros, the Spaniards destroyed a French army. Four years later, at Pavia in Italy, the Spaniards killed or captured almost every French soldier on the field. Francis I was taken prisoner and brought to Madrid. There he promised to be Charles’ “servant and . . . slave,” but he used all his charm to gain freedom. He signed treaties with Charles, but when he was released he ignored his promises. Then, in 1529, at Landriano, Charles’ soldiers overwhelmed a plague-ridden French army and this time the French were crushed.

Charles also fought against the Turks. The Turkish emperor Suleiman the Magnificent, was strong, melancholy and proud. He shaved his head except for one lock, kept a large harem and wrote poetry which he read to his favourite wife. He was a great general and under him the Turks conquered Belgrade m l521. At Mohacs, in 1526‚ they crushed the army of Louis of Hungary, the easy-going brother-in-law of Charles. Louis’ body was found a month later, deep in the mud of a gully. But Suleiman chivalrously kept his soldiers from laying waste to the countryside as they marched up the Danube valley to besiege Vienna. “The Turks’ bold naval ally, Barbarossa the Pirate, was not so kind. His ships infested the Mediterranean Sea and raided Spanish shores. Barbarossa’s pirates carried off thousands of Spaniards to Africa and Turkey, where they joined other Christian slaves in the fields, kitchens and harems of rich Moslems.

Charles fought hack by sending his admiral, Andrea Daria, to raid the Turkish coast. Alarmed, Suleiman’s army retreated from Vienna to protect their homeland. Charles sent a secret agent to get Barbarossa drunk and then poison or behead him, but Barbarossa discovered the plan. He beheaded Charles’ agent. Then Charles raised an armada of 400 ships and sent 30,000 men to capture Barbarossa’s stronghold, Tunis. Charles’ soldiers conquered the pirates; while they sacked Tunis, killing Moslems and setting Christians free, Barbarossa escaped. Later a second Spanish armada was sent after the pirates, but it was wrecked in a great storm.

Wearied by his long struggle, Charles finally gave up Spain and the empire. He had his brother made Holy Roman Emperor and ruler of Austria. To his son Philip he gave Spain, the Netherlands and his other lands. Then, in 1556, he retired to the Convent of Yuste. He spent his last years dressed soberly in black, beating himself on penance days with rough pieces of rope until the knots were worn away and writing political dispatches to Philip. He slept under Titian’s painting of “The Last Judgment.” In September of 1558, after a long illness, he cried “Oh, Lord, I go,” and died.

THE BATTLE OF LEPANTO

Philip II replaced his father as the mightiest ruler of the age. He was a light-haired man who loved music and played his own songs on the guitar. Philip’s enemies said that he was a bloodthirsty tyrant. They charged that he had chopped off the head of his half-mad son Don Carlos, who then sane had been gay and generous, but when mad had roasted rabbits alive. But Don Carlos had actually died of pneumonia, after sleeping on a bed of ice in the summer. The false tales were Spread mainly because Philip had taken up his father’s task of defending the Catholic faith throughout all Europe.

Philip fought the Turks, and on October 7, 1571, his fleet, accompanied by Venetian ships and some vessels sent by the Pope, sailed into the Bay of Lepanto. Led by Philip’s half-brother Don John of Austria, they attacked the two hundred galleys of the Turkish navy. They grappled and boarded the Turkish ships, and fired furiously at the Turkish sailors. At the end of three hours, almost every Turkish ship was sinking. The Spanish victory was “the noblest occasion that past or present ages have seen,” according to the Spanish novelist Cervantes, who lost an arm at Lepanto. Later the Turks built another fleet and bragged, “You have merely shaven our beard, and a shaven beard grows stronger than ever.” The Turks never again commanded the Mediterranean Sea.

In 1580, Philip made himself king of Portugal and in Spain itself he strengthened his rule. He kept the grandees carefully in hand. As members of his royal household, they waited on him like servants, helped dress him, and served his food at banquets. They considered these duties an honour and even fought for them. Philip ruled firmly through his royal council and the Inquisition. When, to his shock, a few Protestants were discovered in Spain, he promptly had them executed. Gold poured in from the New World and Spanish authors wrote the greatest poems, stories and plays that Spain has ever produced.

WILLIAM THE SILENT

Meanwhile, the Protestants were becoming more numerous and aggressive. One Catholic ruler who learned this was Philip’s half-sister, Margaret of Parma. A deep-voiced countess with a mustache, Margaret was Philip‘s regent in his richest province, the Netherlands. In 1566, a group of Protestant Dutch nobles, fully armed, demanded of Margaret that the Inquisition be abolished. They insisted that an assembly of the Netherlands be called to decide the religion of the country and that Dutchmen replace Spaniards and other foreigners in the country’s government. Philip had once before refused such demands from the Netherlands. Now, while he slowly prepared a reply, the Protestants broke into a rage. In four days in mid-August they raided and looted 400 Catholic churches and monasteries, even stripping the great Cathedral of Antwerp of its pictures, statues, gold and jeweled ornaments.

Philip sent the Duke of Alba against the Dutch with a strong army, and in Brussels he began a reign of terror. His council executed so many persons that the Dutch called it the Council of Blood. Some Dutch patriots escaped by sea and in the water-locked provinces of Holland and Zealand they gathered their strength, led by the shrewd, talkative William the Silent, Prince of Orange. Once a gourmet whose thirty cooks prepared the finest food in Europe, William was now completely bent on setting the Netherlands free. He was called the Silent because of the secret way he laid his plans.

For decades the Dutch fought for their freedom and the Spaniards tried to reconquer them. Finally the Spaniards were forced to give up. The king of Spain signed away his richest province, partly because the wars he fought to keep it were too expensive.

In spite of owning the largest empire that the world had ever known, in spite of all the treasure of the New World, Spain could not stand the strain of continuous European wars. Faster than the bullion fleets crossed the Pacific and Atlantic to arrive at the docks of Seville, treasure drained out to equip armadas, to buy galleons, cannon, muskets and horses, to pay troops and generals. Staggering taxes were laid on cloth, glass, meat, wine, shoes, furniture — on all kinds of goods. The taxes ruined trade. Castile’s once-proud silk and woolen industries grew so poor that one petition to Philip described the Spaniards as “worse than Indians.” Twice Philip’s government went into bankruptcy. After the second collapse, in 1578, there was hardly a banking house in Europe that would lend an ounce of gold to the country which owned a quarter of the world.

Spain had become a nation only after centuries of bitter Christian struggle against the Moslem Moors. Spanish rulers concentrated on purifying Spain’s Christianity and defending Spain’s Catholic faith abroad, instead of building up the country at home, encouraging trade and building industry. Gold from the New World allowed the Spanish kings to meddle in Europe before they had fully established their might at home. As a result, Spain’s local assemblies retained some power. The tradition of local liberty and local loyalty remained strong and later Spanish kings could not always have their way. While the English people were beginning to struggle for a voice in national affairs, many Spaniards were still fighting for the local privileges of cities, estates and provinces, just as they had done in much earlier times.

Gradually, Spain began to lose its powers. The flow of wealth from the Americas dwindled, the kings were less energetic. The nobles regained many of their old liberties. The last Spanish king of the family of Charles V was his great-great-grandson. He was known as Charles the Bewitched and was so feeble he never learned to walk properly and was never educated. When he died, a new line of kings from the vigorous French royal family came to rule Spain, but it was already too late. Never again would Spain be a great power.