In 1600, the Duke Virginio Orsini‚ nephew of the Medici ruler of Florence, arrived in England. He came to spend the New Year’s holidays and to see for himself the woman who fascinated all Europe. She was Elizabeth, queen of England and she was already a legend. To aristocratic travelers, such as the Duke Orsini, she was the most important tourist sight in England. Years later, she would still be as fascinating as any woman in history, for in her time — the Elizabethan Age — her country flourished as never before and the Renaissance blossomed in England.

As a girl of twenty-five, Elizabeth had come to the throne of a kingdom torn by religious hatred and civil wars. Her towns were poverty stricken, her farmlands unsown and her army and navy devastated by a series of disastrous foreign wars. Her subjects were weary and confused after years in which short-lived monarchs had alternately honoured and defied the pope and the church of England had split away from the church at Rome. Across the English Channel, the kings of France, Spain and other Catholic nations prepared to attack. They were sure that England, with only a woman to lead it, would soon be easily conquered.

THE “FLORENTINE” QUEEN

Yet forty years later, when the Duke Orsini came to London, Elizabeth was still queen, the ruler of a kingdom as great as any in Europe. This seeming miracle was the queen’s own doing. “I know I have but the body of a weak and feeble woman,” she had told her people, “but I have the heart and stomach of a king.” She had lived up to her words, for she proved to have the commanding air of her kingly father and grandfather, Henry VIII and Henry VII. England had never known a cleverer politician. The queen also had the charm and wit of a lively woman and a fiery temper that matched her red hair. Most of all, Elizabeth had the loyalty of her people. Year after year, she made “progresses,” or state journeys about her kingdom, so that the citizens might see her and know that she was queen to them all, not a stranger who sent out orders from a palace in far-off London. Her hosts were country gentlemen who were expected to provide food and beds for the great company of knights and waiting-women she traveled with and a visit of two or three days could put them into debt for four or five years. The people loved seeing the queen and she did her best to let as many of them see her as possible. Her reward was the love of her subjects, who sang her praises in their rough ballads and even came to admire her temper:

A wiser queen never was to be seen

For a woman, or yet a stouter;

For if anything vext her, with that which came next her,

O how she would lay about her.

All this and more the Duke Orsini had heard in Italy. When he had come to England and was invited to be the guest-of-honour at the court celebration of Twelfth Night, he finally met the fabled queen. She delighted him at once, he said, for “she drew near me with the most gracious cheer, speaking Italian so well . . . that I can say that I might have been taking lessons from Boccaccio or the Italian Academy.”

Elizabeth was no less pleased to meet the noble duke who came from Florence. Of the many languages she spoke well, she was most proud of her flawless Italian and she took pride, too, in her perfect Italian manners. Indeed, she sometimes said she was “as it were, half Italian.” She liked to be nicknamed “the Florentine,” and she dressed with Italian magnificence. She was no longer young, her beauty — never great — had fled, so the older she grew the more lavishly she dressed. That was something that her honored guest, a Renaissance Italian, could easily understand. Nor was he surprised to find the queen’s dining hall hung with tapestries of gold and decorated with “vessels of gold and jewels.” All in all, he felt quite at home.

The court that had gathered for dinner seemed familiar, too, for it was a court of gentlemen. Most of the courtiers were “new men” – merchants, lawyers and politicians into whose eager hands had fallen the riches and lands of the old noblemen. Anxious to live up to their new positions and riches, they had copied the clothes, manners, conversation and way of life of the most well-bred gentlemen in the world, the Italians. Many had all but memorized the instructions in Castiglione’s Book of the Courtier and some had outdone the best of their Italian examples.

No nation could boast a more perfect Renaissance man than a young gentleman who had graced Elizabeth’s court, Sir Philip Sidney. Sidney had courage and excelled at swordsmanship, yet his gentle manner and charm were such that he was called “the most beloved man who ever lived.” He was not always in the good graces of Elizabeth, for he sometimes spoke his mind when more cautious men kept silence. The queen rewarded his gallantry by making him a knight and she so valued his presence in her court that time and again she refused him permission to go off to fight the Spaniards or to settle colonies in the New World. When she finally did consent to let him go to a war, she appointed him as an adviser to the officers and forbade him to take part in the fighting. He disobeyed the order and rushed into battle, throwing away his leg armour because a companion had lost his. He was wounded in the thigh; he gave the last water in his canteen to a private whose “need was greater,” he said; and, when he was at last dragged from the field, he was so weak that the doctors could do nothing to help him. He died, not yet thirty-two years old.

In death, Sir Philip Sidney became the ideal for the adventurous and courtly men of the English Renaissance, the poets and scholars, admirals and gentlemen soldiers. Duke Orsini met and admired them when he took dinner with the queen and later, when he was conducted to a great castle ball for the evening’s entertainments. He also saw the splendour and gaiety for which Elizabeth’s court was famous and afterward he wrote about it all in a letter to his wife. He told of the many ladies and knights who began a Grand Ball and of a comic play with music and dances.

ENGLAND’S RENAISSANCE

The comedy may well have been Twelfth Night, a play written especially for the occasion by William Shakespeare. Probably much of the music was also new and in no other court in the world could this performance have been matched. For it was in words and music that the artists of the Elizabethan Age triumphed. Awakening to the Renaissance, England had had its fling with Italian sculpture‚ beginning with the artist Torrigiano who came to London in 1511 to carve the tombs of Henry VII and his wife. In the same year, the great Erasmus had come to Cambridge to speak with the New English humanists Colet, Grocyn and Linacre — adventurous philosophers who had studied in Rome, Florence and Padua. The English had become eager patrons of artists from the Low Countries and Henry VIII had been pleased to have Hans Holbein do his portraits. The “new men” built elegant country palaces modelled after the mansions that the architect Palladio had designed for the Venetian millionaires. In poetry and music, the English artists outdid their foreign teachers and led the world.

The poets, borrowing some words and ideas from the Italians, fashioned verses whose language and spirit echoed the extravagant, adventurous life of the age. Edmund Spenser turned some of Ariosto’s Italian stories into a pageant of chivalry in the book he called The Faerie Queene. Sir Philip Sidney gave new life and loveliness to the little poems called sonnets, which had been made famous by Petrarch in the early days of the Renaissance in Italy. Sidney was only one of many knights who wrote verses — a gentleman was expected to be able to handle his pen as skillfully as he handled his sword.

For the common folk, there were ballads and street-songs and for everyone there were plays. When the trumpets that announced public performances sounded from the rooftop of a theatre – the Curtain, the Swan, the Globe, or the Rose — nobles and shopkeepers alike hurried to take their places. The theatres, shaped like the innyards in which the plays had once been given, were not very grand or comfortable. The pit, the central audience seating, was a dirt clearing where people stood to watch the actors who performed on the little wooden stage that jutted out from one side of the playhouse. Behind the stage was a curtained alcove and above was a gallery or two where the musicians sat and where scenes like the balcony scene in Shakespeare‘s Romeo and Juliet might be played. There was little scenery, but there was no need of it. With words alone the playwrights could transport their audiences to palaces and battlefields, to Spain or Italy or forests in fairyland.

Not since the great tragedies of Greece had there been such plays as these. Tragedies and comedies and dramas of history poured from the pens of a dozen or more Elizabethan playwrights, every one of whom would have been called a genius in another age. Lyly, Kyd, Greene, Peele, Marlowe, Ben Jonson and the others were as stars in a sky where Shakespeare was the sun.

Shakespeare borrowed his stories from the Italian tales of romance, from Plutarch’s histories of the Romans and from the chronicles of English kings. The magic with which he put them on the stage was his own and no other playwright before or since produced so many masterpieces. It was he who wrote Twelfth Night, the comedy which was probably seen at court by the Duke Orsini. One of its characters was named Duke Orsino as a compliment to the noble visitor.

Though many citizens looked down on players as ne’er-do-wells or worse, the queen took delight in their shows. The company for which Shakespeare wrote — and acted — was often invited to perform at the palace. So were several other groups of players. Even the royal chapel sponsored companies of boy actors who played elegant comedies for the pleasure of Elizabeth and her friends.

Music, like drama, was a part of everyday life in the court and in all of England. Nearly every house had its collection of musical instruments — viols and violins, recorders, cornets, guitars, lutes, sackbutts. When a gentleman entertained, he and his family and guests would play the instruments and sing together. The music was usually English, by such composers as Campion and John Dowland, or the famous William Byrd and Orlando Gibbons whose works were sung and copied all over Europe. The queen herself was an expert musician like her father Henry VIII, she sometimes composed as well. Dancing, however was her particular delight and she knew all of the newest steps. When she was past sixty, she startled foreign visitors by joining the courtiers in the boisterous dance called the galliard. Its pattern was five steps and a high, unqueenly leap.

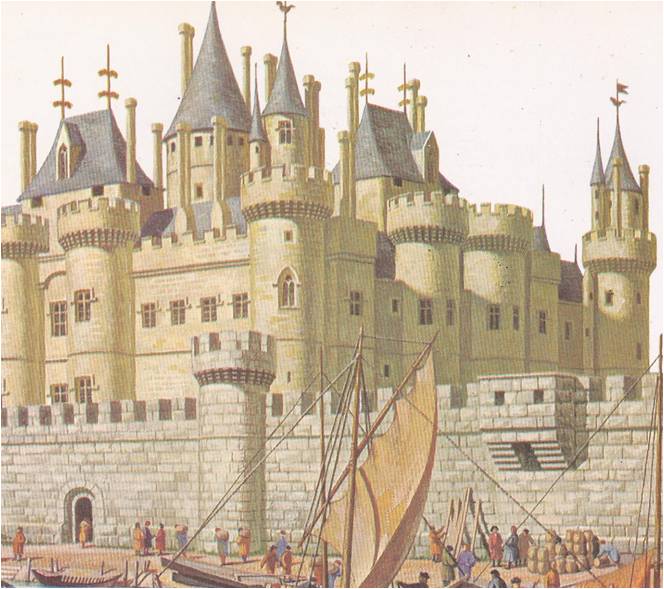

The Duke Orsino did not say whether he joined in the dancing on that Twelfth Night in 1600. He did mingle with the courtiers and was pleased to discover that, though he spoke no English‚ nearly all of them were able to talk to him in his own tongue. It must have seemed strange to hear the soft, warm Florentine words spoken with sharp-edged English accents at a festive ball in a soot-gray castle in London. The language and the trappings of Italy’s Renaissance were to be found in many strange places by 1600. At dinner, the duke noted three odd, awkward ambassadors from Moscow. They had been sent by the tsar, who wanted to learn about the customs and manners of proper gentlemen. In the New World, too, there were settlements whose people were learning the ideas and the art that had begun in Italy.

Italy itself was poorer now and it lacked the spirit that had brought the awakening that was the dawn of the Renaissance. Well-bred Italians were welcomed everywhere. On the way to England, the Duke Orsini had escorted his cousin, Marie de Medici to France, where she became the bride of the king. On his way home, he stopped in Spain, where Elizabeth’s enemies greeted him like a hero and the king presented him with a royal decoration. When he stopped in the Low Countries, he suffered a severe attack of gout — proof that the blood of the Medici had not changed in nearly two hundred years. Unchanged, too, was the spirit of the Medici and the other Renaissance men of Italy; the lifeblood of an age of daring, adventure and soaring ambition, it flowed now through countries far from Italy. When even in England the Renaissance dawn became a sunset, there remained the soaring buildings, the timeless books, the matchless paintings and statues, the ideas that would inspire the men of later ages to try in their own way to do the best that men could do.