March 25, 1436, was the Feast of the Annunciation and the city of Florence was decked out for a celebration. Banners flew everywhere, ribbons and garlands of flowers decorated the houses and draperies of cloth-of-gold were looped across the shop-fronts. The city bustled with excitement, for on this Annunciation Day the pope was to dedicate the Duomo, the wonderful new Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore, then the largest church in the world.

At dawn, the people began to fill the streets. They crowded around the high wooden walk that led to the cathedral from the monastery where the pope was staying. At mid-morning, when a blare of trumpets signaled the start of the ceremonies, a great procession filed along the walk.

The pope, robed in white and crowned with a tiara, was attended by seven cardinals, clothed in scarlet and 37 bishops and archbishops, all in purple. There were the priors, the governors of Florence and the representatives of the people of sixteen districts of the city. Each representative carried a standard marked with the emblem of his district, such as the lion, the unicorn, or the viper. Marching in a solemn line came the leaders of the seven great guilds — the wool merchants, the Silk weavers, the bankers, the notaries, the druggists (who also dealt in spices and jewels), the furriers and the calimala, the ancient and honoured guild of cloth merchants. Behind them came the officers of fourteen “Guilds of Lesser Arts” shoemakers, bakers, innkeepers, grocers, carpenters and the like.

As the procession entered the cathedral, all the church bells in Florence rang out. Their deep voices called across the city, resounded in the fields beyond and echoed in the hills of Tuscany. Triumphantly they proclaimed the greatness of the new Duomo that the Florentines said “rose above the skies, big enough that its shadow could cover all the Tuscan people.”

That was a proud day for the people of Florence, especially for the men of the guilds. The Duomo was a sign of the wealth and power of the city they had made great, the city that the world would one day call the first capital of the Renaissance.

In the early Middle Ages, Florence had been a rising country town lorded over by a tribe of brawling nobles. It was located near the ancient, half-forgotten trade routes to Europe and about 1200, the ancestors of the guildsmen set out in search of markets and trade. At first, they dealt in woollen cloth. They brought home the rough cloth woven in northern Europe, softened and dyed it by a special Florentine process and shipped it north again to be sold at higher prices. Later, they began to work with Silk and damask, velvet — cloth from Florence came to be known as the finest in Europe. As the traders made fortunes in gold, they began to act as bankers and moneylenders. Soon they had offices in Flanders, France and England, as well as in Italy. They did business not only with merchants but also with kings, who borrowed money to pay the high cost of waging war.

THE MERCHANTS’ REPUBLIC

As the merchants grew rich, the old noblemen, too proud to go into business, grew poor and lost their power. The merchants quietly edged them out of the way and in 1293, the guildsmen and the townspeople proclaimed Florence a republic. According to the new laws, the signory, or city council, was made up of common citizens elected from the sixteen districts of the city. The priors, the eight “rulers” who dealt with matters of war and peace and taxes, were chosen from among the members of the seven great guilds and the fourteen lesser guilds.

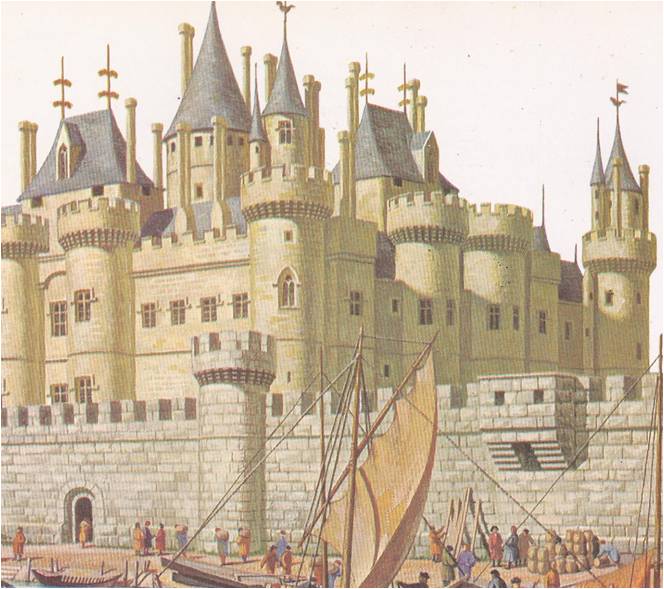

The merchant-rulers of the new republic faced many dangers. Florence was surrounded by larger states — Milan, greedy and strong, to the north; restless Rome and warlike Naples to the south. The smaller states, dotting the hills to the east, were ruled by tyrants who lived by making war for loot and gold. The route to the west and the sea was blocked by well-defended Pisa and by Lucca, whose people hated the Florentines.

In a hard-headed, businesslike way, the guildsmen set out to give their republic the things it needed if it was to avoid being gobbled up by its neighbours. They wanted more land, greater power, allies abroad and clever diplomats at home. They put their money to work, buying allies and hiring armies of professional soldiers to light their wars. They learned to bargain with ambassadors, using the same skill that allowed them to get the better of the wily Flanders wool merchants.

The guildsmen made Florence one of the great powers of Italy and while they were about it, they proved to their neighbors, the proud Italian dukes and counts, that a city governed by commoners could be as splendid as any ruled by noblemen. They built castle-like houses, lofty churches and a great towered palace for the signory. They bought paintings and statues. When Petrarch and his followers stirred their interest in Cicero and the Romans, they began to collect ancient manuscripts and to hire humanist scholars to teach their children. Florence became known as the place where the oldest learning and the newest ideas were both welcome — and well paid for.

About 1330, the city’s merchants gave work to Giotto da Bondone, an artist who broke all the old rules of painting. Giotto tried to paint people and scenes that looked real and full of life. With Giotto, the Renaissance way of painting began and Florence became the city of artists. By 1420, dozens of painters, sculptors, goldsmiths and architects were at work in Florence. Like Giotto, they wanted to show nature as it really was. Young Masaccio, for example, tried to put into his paintings the strength, life and action he saw in Greek and Roman statues. “Masaccio,” said another artist, “makes his figures stand on their feet.” Later came Andrea del Castagno and Paolo Uccello, who made pictures of buildings that stood on their foundations instead of lying flat and out of shape on the walls or panels on which they were painted.

The master sculptor Lorenzo Ghiberti worked for twenty years to make two pairs of bronze doors for the baptistery of the cathedral. He covered the metal panels with lifelike figures that set the standard for every sculptor who came after him. Two younger artists, Donatello and Brunelleschi, went to Rome to study the old statues and ruins. When they returned to Florence, Donatello became the greatest sculptor of his day and Brunelleschi designed the dome of the cathedral, a feat of architecture as grand and daring as anything done by the Roman engineers.

In the years when the Duomo was being built, Florence was famous, busy and rich. The townspeople, the men who wove the cloth and paid the taxes, lived in poverty and had nothing to say about the running of the city. The republic’s government, like its money, was in the hands of a new set of aristocrats, a few important merchants who belonged to the great guilds. To make matters worse, these new merchant-princes were divided into feuding groups, each with its gang of followers. Elections were marked by riots and murders, losing candidates were sent into exile and street fights were common. By 1433, the people had had enough. They resolved to overthrow their aristocratic masters. Curiously, the man they chose to lead them was a wealthy and important guildsman.

Cosimo de’ Medici was the head of a family whose ancestors had won a name as friends of the commoners. Cosimo was a merchant and had no intention of being a politician. Indeed, his father, old Giovanni de’ Bicci de’ Medici, had warned him that a wise merchant avoided politics and stuck to business. By following his own advice, Giovanni had made himself the richest banker in Florence. When Cosimo was asked to lead the campaign against the merchant-princes, he at first refused. Then he began to consider the danger that came with unrest among the city‘s workers. Unless someone did something about politics, he thought, he soon might have no business to tend. So he agreed to help the people.

From that moment on, for more than three hundred years, the men of the Medici family were political leaders and for most of that time the history of Florence was the story of the Medici. The story did not begin very hopefully. When the aristocrats learned that Cosimo was working against them, they had him arrested and put on trial as an enemy of the state. He was too ambitious, they told the judges, too rich and his house was too big. They called for the death sentence. Cosimo had a bribe smuggled to the chief of his judges and instead of the death penalty, he and all the men of his family were sentenced to exile for ten years.

That was in September, 1433. Exactly a year later, the Medici returned to Florence in triumph, while their enemies, the merchant-aristocrats, fled into exile. The people had elected a new council, one that was filled with Medici supporters, and Cosimo came home to take charge of the city.

COSIMO DE’ MEDICI

Cosimo was the master of Florence as long as he lived, for he became an expert at politics — of a special Florentine kind. He ruled by pretending not to rule at all. Instead of holding public office himself, he saw to it that the council was filled with his friends. A slight change or two in the voting laws made it impossible for his friends to lose elections. The people did not realize that they had less to say about their government than ever, but the city prospered and Cosimo was careful never to take the credit for it himself.

Though he was the richest and most important banker in Europe, Cosimo lived simply, ate plain food and dressed in the long dark cloak of an ordinary merchant. When he decided to build a new Medici palace, Brunelleschi brought him the plans for a mammoth building of great splendour. Cosimo turned them down. “Envy,” he told the architect, “is a plant that should not be watered.” Brunelleschi stomped off in a fury and Cosimo hired another architect, Michelozzo, to plan a palace that was less grand. Brunelleschi was not angry for long. Cosimo put him to work designing churches and told him he could make them as splendid as he pleased.

Cautious Cosimo was willing to spend his money lavishly on things that brought glory to the city and not to the Medici alone. He planned the magnificent dedication of the Duomo and helped to pay for the celebrations. He built monasteries and churches, filled the city parks with ancient statues and hired the best professors for the university. His agents roamed Europe in search of old manuscripts. He kept forty-five scribes busy, copying hundreds of books, which he placed in a library for the use of students and teachers — Europe’s first public library. Many of the books were in Greek. Few men in Florence could read that ancient language, and Cosimo had trouble finding one in Italy who knew it well enough to teach it. He provided a lifetime salary for a promising young Florentine, Marsilio Ficino, on condition that the boy spend his time learning Greek and translating into Latin the works of the great Greek philosopher Plato.

The artists of Florence also benefited from Cosimo’s generosity. His favorites were the sculptor Donatello and two artist-monks, painters who were as different from each other as two men could be. Fra Angelico, a simple devout friar, painted because it was the only way he knew to tell mankind of the goodness of God and the joys of heaven. Fra Filippo Lippi preferred the joys of earth — good wine, good cheer, good friends and pretty women. His wild adventures kept him in constant trouble with the city judges and the head of his monastery. Filippo could paint. He could bring to life the stories of the Bible by showing them as though they had happened in the countryside around Florence. For the sake of such pictures, Cosimo saw to it that Filippo was never punished too severely for his misdeeds.

For thirty years, Cosimo watched over the artists and scholars, politicians and merchants of Florence. At seventy-five, he still tried to keep an eye on the government and his bank, but he was weary. Gout and a series of other illnesses robbed him of his strength. One of his two sons died and the other, Piero, was crippled with gout. The Medici palace became a lonely place. “Too large a house for so small a family,” Cosimo would mutter as he was carried through the great silent rooms.

In 1464, Cosimo died. He was buried in one of Brunelleschi’s splendid churches, San Lorenzo and on the tomb were carved the Latin words Pater patriae –“The Father of his Country.”

In his will, Cosimo left a little farm to Donatello, who had grown too old to continue his work as a sculptor. A year or so later, Donatello rapped humbly at the back door of the Medici palace and asked if he might give back the farm. With the crops to worry about, he said, and the weather and the farm workers, there was no peace in the country. If he could have only a small allowance of money, he added hopefully, he could retire to the city.

PIERO DE’ MEDICI

Cosimo’s son, Piero, gave Donatello his allowance and sighed as he watched the old sculptor amble happily on his way. Piero would gladly have traded his own inheritance — the government of Florence with all its problems — for a life of peace. His advisors were ambitious and full of plots‚ the townspeople were restless, there was new trouble with Milan and always there was his gout, so painful that it was a struggle for him merely to get out of bed.

Somehow, Piero overcame his rivals and kept order in the city. He met ambassadors and looked after his bank, raised his children and saw them married to well-chosen husbands and wives. For Lorenzo, the elder of his two sons, Piero found a bride who seemed ideal — Clarice Orsini, the slender, fair-faced daughter of an old Roman family.

Her uncle was a cardinal and her father was one of the greatest generals in Italy. The people of Florence disapproved of Piero’s choice of a bride for young Lorenzo. It seemed to them that the Medici were beginning to act too much like noblemen, who married for the sake of allies and power. Florence was still a republic, they said, the sons of its merchants ought to marry merchants’ daughters.

Piero went ahead with plans for the wedding. To celebrate the betrothal, he proclaimed a public holiday and staged an old-fashioned tournament. The young men of Florence dressed up in gilded armour and plumed helmets, like knights and knocked each other off horses with lances in the most chivalrous fashion. Musicians played, banners waved, the knights paraded and ladies tossed flower garlands to their favourites. Lorenzo won the prize and the crowd began to think that the wedding might possibly be a good idea after all.

When the marriage took place, in June of 1469, Piero ordered three days of celebrations. He provided live feasts at which the Florentines consumed 155 calves, 4,000 capons, 5,000 pounds of sweetmeats and dozens of casks of fine wine. The wedding was a great success and everyone enjoyed himself thoroughly — everyone, that is, but Piero. He was too sick to leave his room, and, in December, he died.

Now young Lorenzo became the head of the Medici family and the leader of Florence. Though he was only twenty-one years old, he had often assisted his father in government matters and was well prepared to take charge of the city. He chose a council of wise, loyal friends to advise him; maintained his grandfather’s policy of peace and for nine years, all was well. Then, in 1478 came the Pazzi Conspiracy — a plot against the Medici, which began with murder and nearly ended with the destruction of Florence.

The Plot was the work of the Riarios, the power-hungry nephews of Pope Sixtus IV and of the Pazzi, an old Florentine family who envied the honor and power that had come to the Medici. In the early spring of 1478, they obtained the help of Archbishop Salviati of Pisa, a lifelong foe of Lorenzo and his father. Together they worked out a scheme to rid Florence of the Medici forever: they would murder Lorenzo and his brother Giuliano and would take over the city’s government themselves.

LORENZO DE’ MEDICI

In the week before Easter, Francesco, Archbishop Salviati and some of their followers came to Florence for what they said was a friendly visit. Lorenzo, suspecting nothing, welcomed them to the city and announced that he would give a banquet in their honour on Saturday night. The conspirators decided to do their killing during the party. A hired assassin would stab Lorenzo while Francesco Pazzi and his friend Bernardo Bandini attacked Giuliano. It was important, of course, that both brothers be killed at the same time. As soon as they were dead, Archbishop Salviati would rush to the palace of the signory to take over the government.

Things did not go quite as planned, for Giuliano had injured his knee and did not attend the banquet. The killings were postponed until the next morning, Easter Sunday. Both brothers would surely go to Easter Mass at the Duomo and in the cathedral they would be off their guard. The hired killer, however, refused to practice his trade in a church, and two monks volunteered to take his place. On Easter morning, Lorenzo came to the cathedral; as usual, he was unarmed and without a bodyguard but, once again, Giuliano did not appear. Francesco and Bernardo rushed to his house. Laughingly scolding him for letting so slight an injury keep him away from church, they finally persuaded him to come with them to the Duomo.

The cathedral was jammed with worshippers. As always, they bowed their heads at the solemn moment in the Mass when the priest lifted the Host. This was the killers’ signal to strike. As Giuliano bowed his head, Bernardo drove a dagger into his back. Francesco leapt to finish him off, stabbing with such fury that he severely wounded his own leg. The two monks acted less quickly. Dodging the blows of their daggers, Lorenzo escaped with a cut on his shoulder. His friends immediately surrounded him. They hurried him into the sacristy, where they barred the heavy doors and waited until the frightened crowd had fled the cathedral. Then they formed themselves into a bodyguard, and led him to his palace.

Meanwhile, old Jacopo de’ Pazzi, so feeble that he could hardly climb onto his horse, was clattering about the city shouting, “Liberty and the Republic!” But the people knew now that Lorenzo was alive and well. They howled Medici slogans at Jacopo until he spurred his horse through the nearest gate in the city wall and galloped away for his life.

At the palace of the signory, Archbishop Salviati was also in trouble. When he went to the council chamber to take charge of the government, the councillors stared at him in wonder, then put him under arrest. He called out to the men he had brought with him, but no one came. By accident, they had locked themselves in a room downstairs. Now an angry crowd began to gather in the square before the palace, shrieking for vengeance. The councillors obliged them by hanging Archbishop Salviati from the window of the council chamber. The mob shouted for more, so the councillors tossed a few of the archbishop’s henchmen out the window to smash on the cobblestones below. Still the crowd was unsatisfied. They rushed to the house of the Pazzi, dragged the wounded Francesco from his bed and carried him back to the palace of the signory, where he was hanged beside the Archbishop.

During the next four days, the Florentines saw to the executions of seventy other men. They hunted down anyone who had had the least connection with the Pazzi plot. The killings went on for months, until hundreds of men had died.

The news soon reached Rome, to the Riarios and their uncle, Pope Sixtus. Though the pope had not given his approval to the plot, neither had he forbidden it. Now that it had failed, he was furious. He ordered the Florentines to send Lorenzo to him to be tried for the murder of Archbishop Salviati. When they refused, he excommunicated all of Florence, commanded every Catholic in the world to stop trading with the city’s merchants and called for the rulers of Italy and all Europe to destroy the city. One king was quick to answer the pope’s call to arms — King Ferrante of Naples, the strongest and craftiest ruler in Italy. He marched his tough, well-trained warriors into Tuscany and they trampled over the half-hearted army that the Florentines had hired to defend their territory.

LORENZO’S DARING

By the autumn of 1479, the crops had been destroyed, the Tuscan towns looted, Florence’s trade cut off and its treasury emptied. A winter truce provided relief for the moment, but Lorenzo knew his city could not hold out if the fighting began again in spring. The only hope was peace.

Lorenzo hit on a daring plan. He slipped away to Pisa and sailed to Naples. Alone and unarmed‚ he let himself be taken prisoner and put himself at the mercy of King Ferrante, a man famed for his heartlessness and treachery. For two months, Lorenzo was Ferrante’s prisoner and honored guest. The king was impressed with his courage, he was pleased by his gracious manner and gradually he was convinced by his arguments for peace. At last, Ferrante agreed not to attack Florence again, no matter what the pope might say.

The pope said a great deal, all of it angry, but he finally made peace with Florence and Lorenzo. He had a good reason. Turks overrunning Asia Minor had turned westward to beat at the frontiers of Europe. Italy was threatened and it was not a time for the states of Christendom to fight among themselves.

In Florence, there were some citizens who said that Lorenzo’s trip to Naples had been foolhardy. He could have stayed home and still have come to terms with Ferrante. When Lorenzo returned from Naples, most of the Florentines greeted him as a hero. The bells of the cathedral rang out to proclaim the peace. To many men, it seemed that the bells also proclaimed the greatness of Lorenzo de’ Medici, whose courage and wisdom, like the shadow of the towering Duomo, were great enough to shelter all the people of Tuscany.