In all Europe there was no greater admirer of Italy than Francis I, king of France. Francis practiced Italian manners in his court, built Italian palaces in his parks and kept Italian books in his library. He collected Italian paintings and the artists who painted them. Indeed, the king admired Italy so much that he wanted to conquer it all.

Francis was not the first ruler to feel these strong Italian longings. In England, Spain and Germany, kings and princes were busily remodeling their courts, their castles and themselves in the Italian manner. Though the little states of Italy were growing poor and weak, it seemed that every richer, stronger nation in Europe was struggling to catch up with them.

Actually, it was the Renaissance that Francis and the others were striving to match — the displays of splendour, the well-bred elegance of the courts, the wisdom, and of course, the riches. Western Europe was waking up to the new age, after long years of poverty, confusion and fear brought on by the wars and plagues that destroyed the old world of chivalry. Through the Alps from Italy came an army of peaceful invaders, merchants first, then artists and men of learning. Along with their bolts of wool and Silk, their books and paintings, they brought the Renaissance. The Europeans, gradually stirring with the excitement of the new age, turned to Italy where its wonders had first appeared. Some sent their scholars and artists to Italy to study. Some, like the French, sent their troops.

In 1494, little Charles VIII of France clapped a gilded helmet over his shaggy red hair, marched down the peninsula and conquered Naples. For three months he paraded about his new city, while four embarrassed Neapolitan noblemen trotted beside him, holding a golden canopy over his proud royal head. Then an allied Italian army attacked and he scurried home.

In 1499, the next king of France, Louis XII, had his try at conquering Italy. He laid claim to Milan and succeeded in capturing the city from Lodovico Sforza. Louis was so fond of Italian art that he considered taking home the wall on which Leonardo da Vinci had painted his Last Supper. The king’s advisers persuaded him to leave the wall where it was and Pope Julius, with the help of a Spanish army, persuaded him to leave Milan to the Italians.

When Louis XII died, in 1515, Francis I came to the throne of France. He, too, rushed through the Alps to conquer Milan and developed a fondness for Italian art. Francis’ methods were more practical than Louis’ had been. He simply offered Leonardo a salary of 7,000 pieces of gold and “a palace of his own choosing in the finest region in France,” and took the artist home to paint new pictures.

Leonardo felt happy and quite at home in France. The king appointed him “Painter, Engineer, King’s Architect and State Mechanician,” and for once, his titles and his jobs almost matched his talents. In a place of honour in the king’s art collection, he found his painting of Mona Lisa and working in the court he found a number of his friends from Italy. Benvenuto Cellini, a swaggering rogue from Rome, was now in Paris, making good his boasts that he could mold gold and gems into the most exquisite knickknacks that any king had ever owned. Il Rosso Fiorentino was teaching French artists to paint in the Florentine way and Francesco Primaticcio was covering the walls of French palaces with the pictures of rosy goddesses he once had painted in Mantua. Leonardo himself did little painting. As always, he was too busy planning masquerades and pageants, castles and canals. He sketched new inventions in his notebooks, amazed the royal physicians with his knowledge of human anatomy and delighted the king with his courtly conversation.

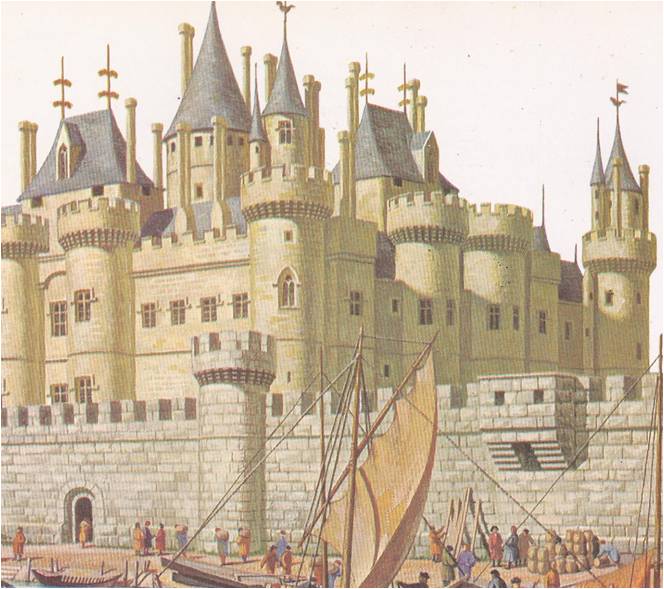

Leonardo’s new master was barely twenty, a young man who was proud of his good manners and handsome looks. Of course, there were those who said that his patience was too short and his nose was too long. Behind his back, they called him Le Roi Grand Nez, “King Big Nose.” But everyone agreed that Francis was graceful, learned and brave, a gentleman who would not have been out of place among the well-bred courtiers of Urbino. His favourite sports were the courtier’s sports, hunting and tennis. He loved tournaments and duels and looked on war as a chivalrous contest of courage. He wrote verses, delighted in shows of pomp and splendour and kept his artists and architects busy with one grand project after another. In Paris, he built a huge new palace, the Louvre, in the best Italian style. In the forest park called Fontainebleau, he built another splendid palace covered with carvings and paintings.

Francis loved to travel about his kingdom, hunting and staging great tournaments and balls and his noblemen vied with each other to build the most luxurious mansions in which to entertain the court. The beautiful countryside along the River Loire was dotted with the splendid chateaux, or castles, which the noblemen modestly called hunting lodges. These buildings were decked out with Greek columns and carvings, and genuine imitation Roman statues — all the ancient refinements that the French architects had learned from the Italians. Underneath the decorations, the chateaux were solid fortress-castles.

Leonardo had once complained that Lorenzo de’ Medici and his humanist friends had buried themselves in the past. In France, Leonardo found men after his own heart, humanists who revered the past because it taught them to make the most of the present, scholars who were eager to open their eyes to the wonders of the world around them. “Abandon yourself to Nature’s truths and let nothing in the world he unknown to you.” wrote Francois Rabelais. Once a monk but now a poet, Rabelais had fled the strict life of his monastery to enjoy the rich and varied adventures of the world. He was like a man who had come to a banquet after years of dining on bread and water. The more he tasted, the greater was his appetite for the sights and sounds and feelings which his brother monks had not even known existed. He tried to write about them all, splashing words onto his pages as though he feared they would fly away if he didn’t catch them in an instant. His tales of Gargantua and Pantagruel were a mixture of laughter and wisdom, madness and nobility, fantasy and truth — the odd muddled, wonderful mixture that was the world he had discovered.

The motto Rabelais set for his readers was Fay ce que vouldras‚ “Do as you like” and no Frenchman tried harder to live up to it than the king. Headstrong and ambitious, Francis chased after valour, fame and magnificence as eagerly as he chased the deer in his forest at Fontainebleau. The court lived according to his whims. The noblemen competed to become his favourites and his favour shifted from day to day. The state treasury was regularly emptied to pay for his extravagances, for he would have what he wanted no matter what it cost. Italy alone was denied him. That prize, which he valued above all others, went to his rival, the Emperor Charles V.

“WHAT DO I KNOW?”

Francis’ son, Henri II, led the last French campaign in Italy in 1557. It was a miserable failure, and Henri made his peace with the emperor, agreeing that henceforth the kings of France would admire Italy from their own side of the Alps. Henri did win one Italian prize: his wife, Catherine de’ Medici, the girl-child that Pope Leo had thought could be of no importance diplomatically. Now she was queen of France, the throne of France depended on her Italian riches and the court of France behaved according to her Italian code of manners. When King Henri died, Catherine’s three sons came to the throne, one after the other. They wore the crown, but their mother had the power. For thirty years, France, the nation that once had helped to drive the Medici from Florence, bowed to the rule of a Medici woman.

France had indeed caught up with Italy, but the Italian way of government was not tailored to fit Frenchmen. Bitter religious quarrels and plots among the nobles divided the people and Queen Catherine joined the plotting. The people were relieved when she and the last of her sons died.

The new king, Henri IV, was of a new royal family, the Bourbons, but he set out to rule in an old, practical French way. Henri believed in the baton qui porte paix, “the big stick that brings peace,” and his idea of prosperity was “a chicken in every pot for every peasant on Sunday.” He kept his Italian longings under control and in his time, France again became a nation, united, strong and French.

In King Henri’s court, power and splendour were mixed with good measures of patience and common sense. Magnificence was very nice, he said, if one could afford it, but no king with a country to run and people to feed could afford to pretend that he was a hero in a legend or a storybook. Henri agreed with a saying he found in a new book, “If we sit on the highest throne in the world, we still sit on our own bottoms.”

The book was the work of Michel de Montaigne, and it was filled with sayings that pleased the practical-minded French. Montaigne’s motto — Que sais-je, “What do I know?”– had become the motto for the new humanists of France, scholars and philosophers who looked on the world and themselves with cautious reason. When Montaigne sought ancient wisdom he turned, not to Caesar with his stories of victories and conquest, but to Plutarch, a Roman who had written of the weakness and foibles as well as the triumphs of the world’s great men.

“Glory and peace of mind,” Montaigne said, “can never be bedfellows.” He chose peace of mind. That was not the Italian way of looking at things — not the Renaissance way. Montaigne was French and in France the Renaissance race was nearly run out. There would be new palaces in Paris, new victories and new discoveries, but they would be the work of men who counted their gold before they spent it, made careful plans before they acted and looked to logic as well as fame. One day these Frenchmen would lead Europe from the Renaissance into a new age, the Age of Reason.