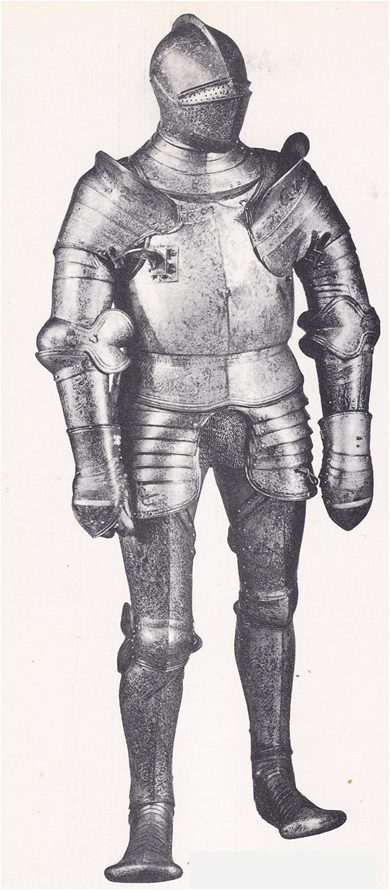

Milan’s most important business street had no displays of velvet cloaks, bright bolts of silk, or cloth-of-gold. It was a dusty, smoky street, made hot by the fires of forges and filled with the din of hammers shaping steel — the Street of the Armourers. Milan made the finest armour in the world. In the Middle Ages, the crusaders came there for chain mail and it was said that entire armies were outfitted in a few days. Later, the fashions of war changed. Knights wore heavy suits of jointed steel plates that covered them from head to toe and elegant helmets, gilded, engraved and topped with plumes. The Milanese armourers became artists at molding and carving metal, their sales men were welcomed in every court in Europe and the Street of the Armourers became busier than ever.

Armour was the right specialty for Milan, for the city and its rulers seemed to specialize in everything warlike and violent. The dukes of Milan were iron-fisted tyrants, who loved displays of splendour and sometimes cruelty. They did not hide their power like the cautious Medici in Florence. Indeed, they made a show of their strength and wealth. It discouraged invaders, rivals and over-ambitious relatives.

The dukes’ domain was rich and as large as any state in Italy. The fertile plain of Lombardy, which lay between the Apennine Mountains and the Alps, attracted as many would-be conquerors as farmers. The prosperous little Lombard towns that the dukes overpowered were quarrelsome and the noblemen of Lombardy never stopped stirring up revolts. To hold on to their dukedom, the rulers of Milan employed the toughest warriors in Italy. They frightened their subjects with harsh laws, rewarded them with pageants and impressed them with magnificent palaces. Splendour, fear and power — these were the specialties of violent Milan and of the two ruthless families who made themselves the masters of the dukedom: the Visconti and later, the Sforza.

It was the Visconti who turned the city of Milan into a mighty dukedom, pushing its borders out across the Lombard plain, filling its treasury with gold and collecting towns as some men collected paintings. The Visconti emblem was a viper, a poisonous snake. The emblem was well chosen, for the Visconti fought with cunning as well as with swords and either way they were deadly. Matteo Visconti, chief of the family of “viscounts” or knights who served the archbishop of Milan, came to power in 1277, when his Uncle Otto was appointed archbishop. Uncle Otto had the chiefs of the rival clans of Milanese knights locked up in iron cages. He proclaimed his nephew as the ruler of the city and persuaded the Holy Roman Emperor to make it official by naming Matteo count of Milan.

That was one of the few times that a Visconti went out of his way to help a relative. As Milan grew in size and wealth, family quarrels — and family murders — became the rule. Brothers, nephews and cousins busily plotted one another’s downfall. Matteo’s four burly sons, weary of waiting for him to die, imprisoned him in one of his own castles, claimed Milan for themselves and then turned on each other. When the last of them was dead, Matteo’s three grandsons began to feud. One met a sudden, well-planned death and his brothers, not wishing to share his fate, agreed to share the family lands instead. They divided the cities of Lombardy among themselves.

The city of Milan, to its great misfortune, fell to the brother called Bernabo. Bernabo’s taxes were mercilessly high, his laws harsh. Any citizen who dared to disobey faced forty days of forty kinds of tortures. Bernabo boasted that his tortures were as painful and unusual as any known in Europe — he had invented them himself. He had his good-humored side: he loved to hunt and he was so fond of his 5,000 boarhounds that he gave them to his peasants to feed and care for. Of course, he sent his soldiers around to make certain that the dogs were well fed, whether the peasants ate or not.

Things were very different in Pavia, the city that Bernabo’s brother Galeazzo made his capital. Magnificence, not cruelty, was Galeazzo’s weakness and his passion. He spent fortunes on palaces and churches, festivals and shows, books and art –anything that would add to the splendour of his court and impress the high-born visitors he loved to entertain. Galeazzo longed to prove himself the equal of those kings and dukes whose families had reigned in Europe since the age of chivalry. To wed his daughter to a genuine royal prince, the son of King Edward III of England, he gave a dowry of 200,000 florins (about $5,000,000) and five Italian towns. He paid almost as much again to see his nine-year-old son, Gian Galeazzo, married to a princess of France.

THE TIMID CONQUEROR

When Galeazzo died, in 1378, young Gian Galeazzo was twenty-seven. He inherited his father’s lands and gold, the most elegant court in Italy and the hatred of his Uncle Bernabo. Bernabo had nine daughters to marry to expensive husbands and five sons as cruel and ambitious as he was himself. He had long envied his brother’s wealth and now he meant to take it from his brother’s son. He knew that Gian Galeazzo was a quiet and studious boy, always at his books, never hunting or flirting with the girls. He was a coward, who frantically fled to safety at the first sign of a fight. Indeed, he seemed so timid, so different from his rough cousins in Milan, that it was hard to believe he was a Visconti at all. Certainly, Bernabo thought, he would make an easy victim when the time came.

In 1385, Gian Galeazzo announced that he was going on a pilgrimage to a religious shrine at Varese. No one thought it odd that he hired a troop of German soldiers to guard him along the way, for by now his cowardice was famous. The road to Varese led past Milan. When Gian Galeazzo came to the city, he stopped outside the gates, but nothing could persuade him to go inside. Bernabo, delighted at this show of fear, rode out with two of his sons and gave a scornful greeting to his nephew. Gian Galeazzo returned the greeting politely, then spoke a word in German to his troops. They immediately surrounded Bernabo and his sons and made them prisoners.

Never again did anyone doubt that Gian Galeazzo was a true Visconti. Milan, with all its land and towns and gold, was his. The people welcomed him with joyful shouts: “Long live the count and down with the taxes!” As bookish as ever, Gian Galeazzo worked hard at governing his state, pouring over his account books like a merchant. Under his care, Milan grew prosperous and strong. Weavers, silk merchants, goldsmiths and jewelers became as busy as the armourers. Gian Galeazzo spent his well-counted money on art and fine buildings — new wings for the palace at Pavia and a huge cathedral, the Duomo, for Milan. Since he was still a coward, he also bought courage. He hired soldiers to guard his castles and skillful generals to conquer more of the towns of Lombardy. By 1397, his power was so great that the emperor awarded him the title of Duke of Milan.

Gian Galeazzo began to dream of conquering all Italy. When his soldiers tramped into Tuscany and scattered every army the Florentines sent against them, it seemed that he might succeed. In 402, he was struck down by the plague and his well-ordered dukedom fell apart. His two sons too young to rule, were old enough to renew the Visconti family feuds. While they squabbled, their father’s generals deserted and claimed the towns they had conquered as their own. At last the young duke and his brother agreed to divide the shrunken dukedom.

A COWARDLY DUKE

Gian Galeazzo’s sons also seemed to have divided up the ways of the Visconti. Little Duke Giovanni Maria grew up to be as harsh as Bernabo and even more cruel. His hounds, it was said, were fed on human flesh. In 1412, a group of Milanese noblemen attacked him in a church, killed him and tossed his body into the street. His lands and title went to his brother, Filippo Maria, who was a greater coward than Gian Galeazzo and to make matters worse, ugly and fat. Filippo Maria never allowed his portrait to be painted. He rarely went out where his subjects could see him and he changed his secret living quarters in the palace so often that even his councillors often had difficulty finding him. Filippo Maria had his father’s cunning, ambition and he was determined to win back all of his father’s dukedom. He married the widow of one of the rebel genenls; her dowry was a group of cities stolen from Milan. Then he hired new generals, the best condottieri he could find and sent them out to recapture the other towns.

The business of hiring condottieri was a constant problem for Filippo Maria. He needed them but they filled him with terror, for he was always certain that they meant to steel his dukedom. He tried to buy his commanders’ loyalty with high salaries and set spies on them, just to be sure. He hired one general after another, never trusting one for long and for a time things went well. Then he hired Francesco Sforza, a general he did not want to keep yet could not do without.

Francesco Sforza was known as the toughest condottiere in Italy. In his youth, he had marched with the army commanded by his father, a commoner whose skill in battle had won him the friendship of kings. At 22, when his father died, Francesco was ready to take his place at the head of the troops. He was tall, strong and an expert wrestler, runner and jumper. He had trained himself to get along with little sleep or food and to march bareheaded in summer and winter. He had learned how to command men. He disciplined them strictly. But he won their loyalty by sharing their hardships, taking the risks they took and fighting better than any of them.

Francesco went in search of battles to fight and soon had a series of victories to his credit. Many rulers and cities sought his services. They paid him well and he even won a little land for himself, but he was not satisfied. When Francesco was called to Milan by Filippo Maria, he saw the splendor of Italy’s richest dukedom. This, he thought, was what he wanted; and this, he swore to himself, was what he would have. He began to court the favor of his new master and of Bianca, his master’s only child. Bianca, he knew, could not inherit her father’s title and land. According to the laws of Milan, only a son could do that. Bianca’s husband might be able to claim the dukedom as a son-in-law. Francesco meant to be that son-in-law. He fought Filippo Maria’s battles with extra vigour and then he asked for the hand of his daughter in marriage.

DAUGHTER OR DUKEDOM?

The duke was outraged. He would not, he shrieked, marry Bianca to a common hired soldier. Francesco shrugged his shoulders, resigned and offered his services to the city of Florence, Milan’s most bitter enemy. Filippo Maria hired half a dozen other condottieri, one after another. None could match the great Francesco Sforza and at last the duke was faced with the choice of losing his daughter or his dukedom. He fumed and spluttered and ordered the marriage contract drawn up. Francesco returned to Milan to marry Bianca and defend the lands and towns that, according to his plan, would be his at the death of Filippo Maria.

The people of Milan, however, had other plans. When Filippo Maria died, in 1447, his subjects danced in the streets. For 170 years they had suffered under Visconti tyrants. Now they were free. They were determined to have no new master. Milan would be a republic and they would rule themselves. Francesco did not interfere. He simply waited until the people of Milan, like their old master Filippo Maria, begged him to return, which they did as soon as a Venetian army marched into Lombardy. When he rode up to the city gates, the Milanese greeted him with cheers. Before he could dismount, they rushed him into the cathedral. There, still seated on his horse, he received the blessing of the archbishop who proclaimed him Duke of Milan.

Francesco ruled his dukedom as skillfully as he had won it. He lived simply, worked hard and treated his subjects as justly as he had treated his soldiers. He cared little for the shows of splendour that had delighted the Visconti, though he welcomed artists to Milan and hired a noted humanist, Filelfo, to educate his sons.

Filelfo did his best with the young Sforza, but Francesco’s wife, Bianca, had her own ideas about the proper education for the sons of a duke. She trained her children to be very much like the Visconti. When her eldest son Galeazzo Maria inherited his father’s dukedom in 1466, many of the old Visconti problems returned to plague Milan.

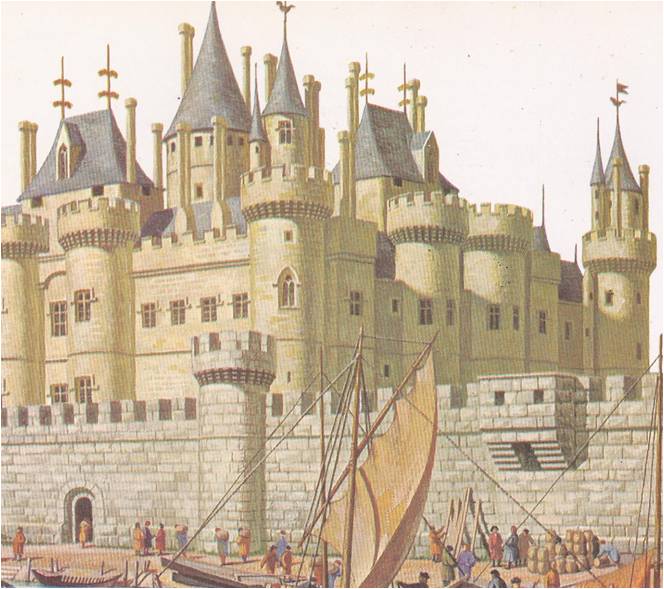

Galeazzo Maria loved power and wealth. Even more, he loved to show them off. His father had built a great family fortress, the Castello Sforzesco, the strongest castle in Italy; Galeazzo Maria set out to make it the most magnificent. At his command, the finest singers from Flanders filled the halls with music, banquets were served on plates of gold and hundreds of servants rushed about in suits of velvet with silver fringes. For important guests of state, there was a special treat. The duke himself took the visiting lords on a tour of his favorite place, his jewel house, where emeralds, sapphires, rubies and diamonds lay in piles like pebbles.

LODOVICO THE MOOR

For the people of Milan, Galeazzo Maria gave countless pageants, processions and tournaments. He also gave them displays of dreadful cruelty. Citizens were tortured in the public squares, merchants were forced to grovel for his favour, courtiers were insulted and dragged off to prison — all so that the duke could show off his power. Galeazzo Maria was indeed a Visconti and he died as one of his Visconti ancestors had died. In December, 1476, three students attacked him in a church and stabbed him to death.

The new duke, Gian Galeazzo II, was a child, too young to take charge of the government. He had four ambitious uncles who were eager to do the job for him. New family quarrels made turmoil in Milan until, suddenly, the contest for power was over. One uncle, Lodovico, got the upper hand. Appointed as the regent to oversee the little duke’s affairs, Lodovico became the most powerful man in Milan, the duke in everything but name.

A dark, brooding man, Lodovico was called “Il Moro,” the Moor. His years at court had taught him to be cunning and ruthless. To safeguard his new power, he had the young duke’s mother imprisoned. He also ordered the beheading of old Secco Simonetta, the faithful ducal secretary who had tried to save the boy’s inheritance from his greedy uncles. Otherwise, Lodovico proved to be a wise and merciful ruler. He sponsored new trades in the city, encouraged farmers to try new crops, built canals and opened schools. Even his cunning was useful to Milan. He became famous as the craftiest diplomat in Italy.

For diplomatic reasons, Lodovico arranged for his nephew the duke to marry Isabella of Aragon, whose grandfather ruled Naples. He himself became engaged to the five-year-old daughter of the Duke of Ferrara, Beatrice d’Este. The wedding was put off until Beatrice had reached sixteen. Then Lodovico set a date — January 17, 1491 — and sent ambassadors to Ferrara with presents for his bride. Among the gifts was a priceless necklace of pearls and tiny flowers of gold with drops of emeralds, pearls and rubies. Lodovico did not expect to love the girl. That would have been asking too much of a diplomatic marriage. He meant to treat her in a way that would please her important relations and of course, do honor to his own wealth and power.

LODOVICO AND BEATRICE

When Beatrice arrived, she was shy and ill-at-ease. The splendour of the wedding, held in the magnificent old palace at Pavia, made her more timid than ever. When the wedding party journeyed to Milan for the court celebrations, Beatrice began to change. She found a city turned into a great carnival. Along the Street of the Armourers, models of mounted knights in glistening steel armour stood like an army on parade. Gay processions of masked revellers filled the squares. There were banquets and dancing, plays and concerts and fireworks. Everywhere, Beatrice saw the riches of Milan displayed and everywhere she was cheered. She began to realize that all this splendour was hers to command and enjoy. Her shyness vanished; she smiled and laughed and blew kisses at her husband. To his surprise, Lodovico found himself falling in love with his wife.

Beatrice turned the old Castello into a place of gaiety. The court became the gathering-place of princes and ambassadors, scholars, poets and philosophers, for all of them were charmed by Lodovico’s sprightly wife. Some citizens complained that she was too proud and too extravagant. Why, she had enough jeweled gowns to wear a different one every day for nearly three months. When Beatrice spent her husband’s gold on pageants, the grandest Milan had ever seen, the people forgot their complaints. After all, Milan was rich and it had never been happier.

Chief among the designers who planned Beatrice’s pageants and masquerades was Leonardo da Vinci. When he decided to leave Florence, the artist had written to Lodovico, asking for a job. Actually, he had asked for many jobs — he could, his letter said, design bridges, make cannon and mortars, plan new kinds of warships, build equipment to tunnel under the walls of enemy cities, construct canals and palaces and invent marvelous weapons the like of which the world had never seen. Not until the last paragraph did Leonardo mention that he was an artist. His work in marble, bronze, clay, or paint, he said, “would stand comparison with that of anyone else, whoever he may be.” He suggested that Lodovico hire him to make a bronze statue of Francesco Sforza on his war horse. Leonardo promised that the statue would “lend immortal glory and eternal honor to the noble memory of the Prince your father and of all the illustrious house of Sforza.”

Lodovico did not hire Leonardo to make the bronze horse. Indeed, he did not mean to hire him at all. A few weeks after the arrival of the extraordinary letter, Leonardo himself turned up at the Castello Sforzesco carrying a silver lute he had made. “A present,” he said, “for Lodovico.” It was a beautiful, tuneful lute and Leonardo a handsome young man with courtly manners and a fine voice for singing ballads. Lodovico decidd that there might be work for him in Milan. Not an architect or military engineer, of course, but as a painter and a planner of pageants and holiday decorations.

Leonardo was a great success in his new post, for he delighted in finery and shows. He designed costumes, modeled masks, decorated palaces and trimmed the ducal stable. He invented fantastic mechanical animals for the entertainment of Lodovico’s royal guests. He painted — portraits of the Sforzas, murals of their palaces and altar pieces for their favorite churches.

About 1490, Lodovico asked Leonardo to do a wall-painting in the dining ball of the Dominican monks who served the church of Santa Maria delle Grazie. Leonardo decided to paint a picture of Christ and his apostles at the Last Supper, a picture in which the soul of each apostle would show in the features of his face and the movement of his body. For months, Leonardo planned, sketched, and, once in a while, painted. He wandered about Milan, staring at faces, searching for features and expressions that might be used as models for the apostles. Sometimes he rushed in from the street, added one or two strokes of paint to one figure, then left again. Sometimes he sat for hours, staring at the picture and adding nothing. To the prior of the monastery, waiting impatiently to be able to use his dining hall again, this looked like dawdling. He complained to Lodovico who, in turn, complained to Leonardo. The artist had no trouble explaining. He worked hardest, he said, when he seemed to work least. Planning and deciding took time; when that was done, painting was easy. Lodovico nodded, sighed and tried to think of a way to explain that to the prior.

It was three years before “The Last Supper” was finished and the monks could once again make use of their dining hall. Meanwhile, Leonardo had started to work on another big project for Lodovico, the bronze statue of Francesco Sforza which he had described in his letter. In 1493, after months of experimenting with sketches, he completed a full-size plaster model of the horse and rider. It stood 23 feet high and Lodovico was so pleased with it that he had it hauled to an archway in the center of Milan where everyone could see and admire it. No one doubted that when it was cast in bronze it would be as great as any statue in ancient Rome. The bronze was collected, some 50 tons of it. Before the work of casting had begun, Lodovico had to use the metal to make cannon. He assured Leonardo that he would buy more bronze for the statue as soon as he could, but months passed, then years and there was never enough money in the state treasury for anything but soldiers’ pay and fortifications.

The ruling family of Milan was once again squabbling for power and this time their quarrels involved all Italy and the kingdom of France. On one side stood Lodovico, who wanted to be duke and Beatrice, who was determined that her son would be the heir to the dukedom. On the other side were Lodovico’s nephew, Duke Gian Galeazzo II, who was not very well and not very bright and Duchess Isabella, who had the courage her husband lacked and a son whose rights she meant to protect. Isabella called for the help of her father, the king of Naples. He promised to invade Milan if Lodovico made himself duke.

FRENCH INVASIONS

Lodovico, in turn, signed a pact with the French king, Charles VIII, whose family had long claimed that Naples belonged to France The Italians howled that Lodovico had betrayed them. In 1494, French troops invaded Italy, marched unopposed through the territory of Milan and headed south to conquer Naples. A few months later, the French again passed through Milan, fleeing before an allied Italian army. By then, however, Lodovico had switched sides in the war, for he no longer needed the protection of France. While the French were in the south, Gian Galeazzo had died and Lodovico had been proclaimed Duke of Milan.

Lodovico and Beatrice had little time to enjoy their triumph. In 1497, Beatrice died. Two years later, the armies of France came back to Italy and their target was Milan. Lodovico’s Italian allies deserted him. Desperate for money and soldiers, he disguised himself and fled to Germany, to seek the help of the emperor. While he was gone, his officers gave up the fight. His most trusted general surrendered the Castello and the French poured into the city. The soldiers ransacked the splendid Sforza palaces, shipping the best of the paintings to Paris for the king. When the French found Leonardo’s plaster model for the statue of Francesco Sforza, they used it for target practice.

Leonardo himself had fled. He had been twenty years in Milan. Now he was a wanderer, going from city to city in search of work, still filling his notebooks with ideas for inventions, still dreaming of making miracles.

Milan’s French governor ruled harshly and the city’s people were eager to fight for Lodovico when he returned with an army of condottieri. Lodovico could not afford to pay the soldiers for long. When his gold was gone, they betrayed him. Again he put on a disguise and tried to flee, but he was captured and taken to France. He never saw Milan again. For years he was held a prisoner in one of the French king’s castles. His dark hair turned white, his straight body grew stooped with age. At last, in the darkness of an underground cell, he sat remembering the bright splendour of a city decorated for a carnival, where fireworks showered above the towers and Beatrice learned to smile. In the darkness, he waited for death and on May 7, 1508, it finally came.

One of Lodovico’s sons also died in prison. The other, Massimiliano, was invited back to rule Milan in 1512. His taxes were high, his manners were rude, his wits were dull. His subjects were relieved when the French sent him into exile in 1515. No new Sforza came to rule Milan and no new family of dukes tried again to mold the rich but quarrelsome towns of Lombardy into a strong, independent state. The French had come and already the Spanish and Germans were thinking about conquest in Italy. They, too, would come first to Lombardy. They would seek the riches and splendour that had made Milan famous and they would find the violence that had made it weak.