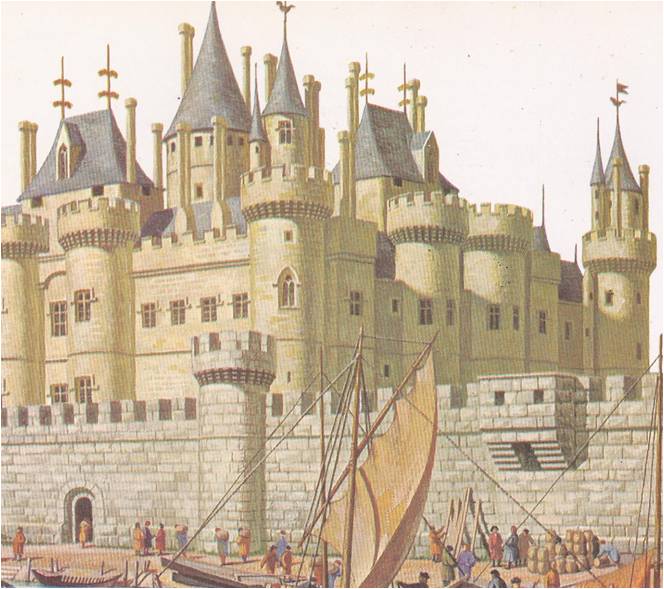

Through the bustling market-towns of the Low Countries passed the traders, goods and gold of all Europe. Here the luxuries of Asia — spices‚ silks, jewels and perfumes — were exchanged for the practical products of the North — woolen cloth and utensils of iron and copper and wood. In shops and inns, wily Italian shippers and bankers bargained with the solemn, solid merchants from Germany and Flanders — and made the profits that built the Renaissance cities of Italy. In tall-spired cathedrals, in palaces, guildhalls and universities, wandering Italian artists discovered works of art and scholarship as great as any they had known at home.

The men of the North had needed no outsiders to teach them about money-making or magnificence. Long before the Renaissance spread across Europe from Italy, they had turned to business, formed the guilds, grown rich and invested their gold in displays of splendour. Flanders was the center of a great cloth-making industry. Germany was the home of expert craftsmen—armourers, goldsmiths and engravers. In Haarlem in the Low Countries, a jack-of-all-trades named Laurent Coster had first thought of using movable carved letters to form words and sentences from which pages could be printed. About 1440, Johann Gutenberg and his assistant Peter Schoeffer had put Coster’s idea to use, made the first printed books and brought about a revolution in learning that changed the history of the world. The northern artists also were inventive and their guildsman patrons kept them as busy as the artists of Italy. Of course, their tastes were not Italian and their paintings and statues, like their ideas, were very different from those in Florence, Milan and Rome.

When Masaccio was first teaching the Florentines how to paint figures that “stood on their feet,” the wool merchants of Flanders were buying paintings from Hubert and Jan Van Eyck. Their pictures were so crowded with sharp details of nature and life that they might almost have been colored photographs. The world in these paintings was richer and more brilliant than any that a camera could have captured. Somewhere — no one knows where or how — the Van Eycks discovered the secret of painting in oils. The colours they used were deep, rich and glowing with light and they wrapped their figures in scarlet mantles, gave crowns of glittering stars to their saints and shimmering jewels to their madonnas and kings. While the Renaissance Italians labored to splash great, sweeping designs across walls, the Van Eycks tried to bring to life every minute detail of a figure or scene within a small painting.

Italians coming north to trade were excited by these pictures, so different from their own. They carried home the secret of oil painting and tried to carry home the artists, too. The king of Naples was greatly disappointed when he failed to persuade Jan Van Eyck to move to his court. Later, when Rogier Van der Weyden, the Van Eycks’ greatest follower, came to Rome for a visit, the Italian artists greeted him like a hero.

PAINTERS AND SCHOLARS

Gradually the arts of the various countries began to blend. While Italians were copying the Flemish techniques of oil painting, German artists were studying books of engravings of Florentine pictures. From them the Germans learned the Italian way of drawing bodies and landscape that were natural, graceful and real. In 1494, Albrecht Dürer, an apprentice from Nuremberg, came to Italy seeking the secrets of art that he said “had been hidden for a thousand years.” A Venetian showed him the mathematical rules for drawing a body of perfect proportions and Dürer exclaimed that this new knowledge was worth more than a kingdom. He hurried home to write a book about painting, despite the complaints of his wife who insisted that the only way to earn a living from pictures was to paint them, not write about them. Dürer’s book — and the paintings and engravings he did do — set all the artists and craftsmen in Germany to imitating the Italians.

The Renaissance love of learning and the past also followed the trade routes north from Italy. In 1517, a Dutch scholar, Erasmus, transformed by the spirit of the new age, wrote, “Immortal God, what a world I see dawning! Why can I not grow young again?” Erasmus had studied with the scholars in Italy; he had traveled to Germany, Switzerland and England to talk with other students of the new learning. They called him “The Prince of Humanism,” and he taught that humanism was a promise of hope in a world that too long had been enslaved by fear and despair.

Even so, Erasmus did not rush to the pleasures of the world or imitate the extravagance of his Italian friends. Indeed, in the ideas of the ancient philosophers he found new reasons for living a life of religion. He was glad to know Greek, because that meant he could read the earliest versions of the New Testament and know what they really said. Over the years, too many churchmen had translated and changed the meaning of the Bible to suit their own beliefs. When Erasmus wrote of the Bible and the Church, he talked of reforms. In his book The Praise of Folly‚ he attacked the silly and senseless customs which had been added to religion by pompous bishops and superstitious peasants.

After Erasmus came Martin Luther, who battled Pope Leo, demanded reforms instead of merely talking about them, and led a revolt from the Church. In Luther’s time, these countries at the ends of the trade routes came under the power of a monarch who collected states as eagerly as some kings collected paintings. In 1516 Charles V became king of Spain, the Low Countries, Naples and Sicily; three years later he inherited the title and lands of his grandfather, the Holy Roman emperor. For nearly thirty-five years he strove to add to his collections. He brought Italy under his sway and fought countless battles to rob his rival, Francis I, of his French provinces. In love with pomp and splendour, Charles seemed determined to collect all of the art of Renaissance Europe as well as all of the land. Paintings by the hundreds were shipped to his capital in Spain.

Then the emperor suffered setbacks in his wars with France. He grew discouraged and ill, in 1555 he retired to a monastery to prepare for death. He divided up his empire between his brother Ferdinand and his son Philip II. The ruling of such a hodgepodge, he said, was too much for one man.

King Philip, who was given Spain, the Low Countries and Naples, also inherited the great art collection. He decided to build a new palace in which he could display his treasures of painting and sculpture. At Escorial, a little town outside the Spanish capital of Madrid, he commanded his architects to erect a single building that would serve as royal court, art gallery, tomb for Spanish kings, monastery and church.

The builders laboured for 21 years and often the king himself supervised the work from a stone throne set on a hilltop two miles away. Gangs of workers, pressed into service by Philip’s soldiers, hauled at huge blocks of stone. Long pack-trains carted in bronze from Italy, iron candelabra from Flanders and rare woods from the New World. Hundreds of new paintings arrived from the art centers of Europe and dozens of artists were hired to cover the palace walls with frescoes. Dozens of artists were also sent home again, for Philip was a particular and stern patron. El Greco, a Greek who had been the finest of the students of Titian and Tintoretto in Venice, failed to win Philip’s favour with the painting he did for the high altar of the palace Church. He was never again offered a royal commission, but he moved to Toledo, a city that welcomed painters, scholars and poets. There he painted the pictures that became the glories of the Spanish Renaissance.

In 1586, the work at Escorial was done and on the eve of the Feast of San Lorenzo, the saint for whom the palace monastery was named, the great building was dedicated. Two hundred thousand oil lamps lit the palace so brightly that the glow could be seen at Toledo, nearly fifty miles away. No amount of light could make cheerful the brooding stone structure that stood for the stern spirit of Spain. The architects had indeed followed the king’s command. Escorial was a symbol of the power of the kings and churchmen who had driven the infidel Moorish conquerors out of Spain and then turned to burning heretics who questioned the doctrines of the Church.

Spain was the country of Cervantes, whose tales of the comic knight Don Quixote make up one of the world’s greatest comedies and of Lope de Vega, whose hundreds of plays are masterpieces acted over and over for centuries. It was also the country of the Inquisitors, the Church judges who punished sin with whippings, torture and execution. Indeed, it was Spaniards who taught the popes at Rome the methods for curing the Church of the worldliness and extravagance that had weakened it in the days of Italy’s Renaissance. They helped to establish an Inquisition for all of Christendom, a committee of churchmen who were given the power to tell men what they might believe and what they might not. Their methods did restore the sanctity of the Church, but they also helped to end the Renaissance.

With all its statues and paintings, it was this harsh, reforming zeal that King Philip’s new palace represented. It stood, too, as the mark of Spanish power which for a time was greater than that of any other nation in the world. The cost of the king’s great palace left his treasury bankrupt. His battle against the new religions of the north brought revolt in his states in the Low Countries and stirred up war with England. Four years after Escorial was dedicated, a great armada of Spanish warships was sunk off the English coast. That disaster signaled the decline of Spain’s power. King Philip fought on until 1598, when he was struck down by gout and fever. He had himself carried from Madrid to Escorial and placed in a tiny bedroom that opened onto the high altar of the monastery church. There he died, leaving behind his collection of the finest art of the Renaissance and his gloomy palace, a monument to the power and the fear that helped to bring the Renaissance to an end.