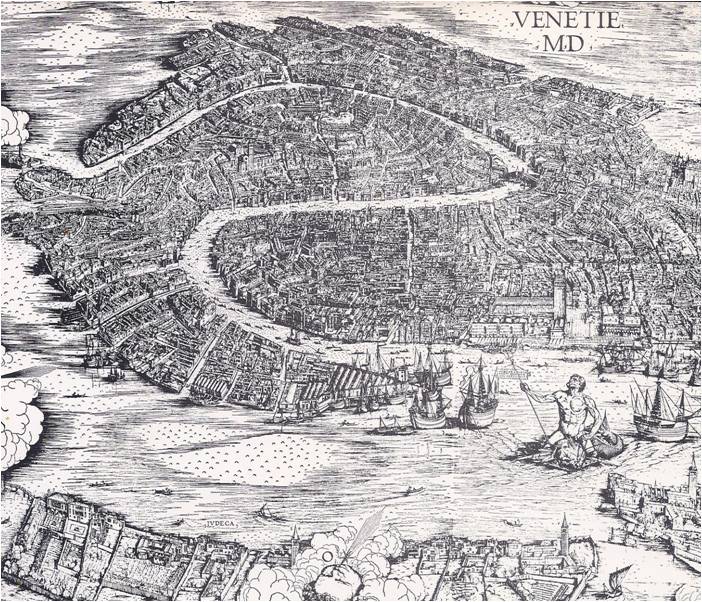

The houses of Venice are “like sea-birds half on sea and half on land,” said Cassiodorus.

An officer of a king of the Goths, Cassiodorus saw Venice in 537. It was a little settlement of huts built on the mud-flats in an out-of-the-way lagoon. Its people were refugees‚ Italians who had been driven from their homes by a horde of barbaric invaders. They were safe in the lagoon, for no stranger could navigate the treacherous channels. For the sake of safety, they were content with comforts that were simple at best. “In this place,” Cassiodorus said, “rich and poor are alike — they all fill up on fish.”

A thousand years later, when Venice had become the richest and most powerful city in Italy, it was still a place of refuge from the wars and turmoil of the mainland. The lagoon was still an unbeatable defense. Instead of streets, there were canals and the city’s mansions, marble palaces and gold-peaked churches still hovered above the water like sea-birds, perched on 117 islands linked by nearly 400 bridges.

In every way, Venice belonged to the sea and for many years the sea belonged to Venice. The descendants of the settlers commanded mighty warships that ruled the eastern Mediterranean. With their great merchant galleys, they were the lords of the trade-routes of the Adriatic and Aegean Seas and they sailed the Atlantic to England and Flanders. In the Middle Ages, the Venetians built and manned the hundreds of ships that took the Crusaders to the Holy Land — and they saw to it that the knights captured a few colonies for Venice along the way. Through the years, these colonies multiplied into an ocean empire until even Constantinople, the capital of the old Roman Empire of the East, paid homage to the power of Venice.

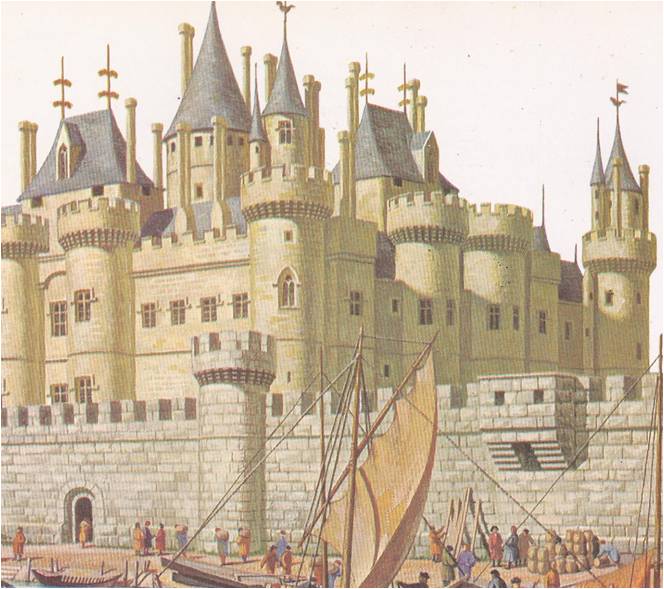

The city’s strength abroad depended on a great shipyard at home, the Arsenal, which was so huge and efficient that its 2,000 workmen could build of repair 100 vessels at one time. Galleys, hauled past rows of workshops and warehouses on a sort of assembly line, were constructed, caulked, painted and outfitted with remarkable speed. All parts and equipment — from masts to oars, from weapons to water barrels — were standardized. Thus spares could be stored at every Venetian port of call, crews could shift from one ship to another without the need for extra training and the Arsenal could turn out a new galley every hundred days.

For 800 years, Venice celebrated its mastery of the sea with a curious ceremony. Each year on Ascension Day, the great state barge, the Bucentaur, sailed from the palace of the doge to the Porto di Lido. The barge was carved and gilded and hung with rich purple cloth. On its throne, beneath a golden canopy, sat the doge, the head of the Venetian government, his head-dress and brocade gown crusted with jewels. Following his barge came a fleet of gilded gondolas carrying councilmen and senators, aristocrats in their crimson togas and ambassadors of foreign states. There were boatloads of musicians and ships decorated with garlands, artificial scenery and images of saints and sea nymphs. At the Porto di Lido, the procession halted. The doge poured an offering of perfumed oil on the water and cast a golden ring into the sea, saying, “O sea, we wed thee in sign of our true and everlasting dominion.”

Wedded to the sea, Venice turned its back on the land, the mainland of Italy. It had no part in the struggles between the pope and the emperor, and did not enter the costly contests for land and power among the rival Italian states. Venice competed for power on the sea, where it was strong and looked to its lagoon for protection. Only twice did enemy ships invade the lagoon; both times the enemy was trapped by the tricky channels and destroyed by the Venetian marines. Genoa, Venice’s strongest rival for the trade routes, was one of the foes who made the mistake of sending their warfleets into the lagoon. When the battle was over, Genoa was no longer a rival.

By 1400, Venice knew no equals on the sea. Venice lived by trading, not by naval battles. Its merchants needed land routes as well as sea routes to reach the wealthy inland cities of Italy and Europe. Its people needed food — cattle and grain grown on the mainland fields. Its traders needed new markets, western markets, because the Turks were gradually nibbling away the eastern empire of islands and seaports.

In 1405, Venice turned west to the mainland, went conquering and prospered. For seventy-five years, the Venetians added to their territory until its frontiers stretched from the Alps in the north to Ferrara in the south. Trade boomed and Venice grew rich. Then the time of expansion came to an abrupt end. The other Italian states, aided by the French, united against Venice. The Venetians‚ facing such a mass of power, decided that they had land enough. Indeed, they were lucky to keep the territory they had already taken.

Meanwhile, the ocean empire was falling apart. In 1453‚ Constantinople was lost to the Turks and ten years later, the savage Turkish hordes threatened Venice itself. The attackers were pushed back, but from that time on the Venetien merchants had to pay tribute in order to trade in the East. The greatness of Venice, the power and wealth that had grown from so little to so much in so short a time, began to fade. Yet, in its last years of greatness, the city was more glorious than it had ever been.

When Philippe de Comines, ambassador of the king of France, came to Venice in 1495, he reported that it was “the most triumphant city I have ever seen.”

Comines sailed along the Grand Canal, Venice’s main thoroughfare, which was lined with palaces. He saw old buildings of bright-painted stone and new ones of white marble with Greek columns, tall windows and stately carved doorways that opened onto the water. He marveled at the palace called Ca d’Oro, or Golden House, whose balconies, columns and carvings were all covered with gilt.

“This is the most beautiful street in the world,” he said. There was greater beauty hidden behind the tall front walls of the palaces. There were courtyards filled with statues and cool gardens where fountains played. There were lofty rooms with floors of marble or colored tile, huge fireplaces, chandeliers of wrought metal and furniture inlaid with ivory and precious metals. There were walls hung with silk or painted with magnificent frescoes.

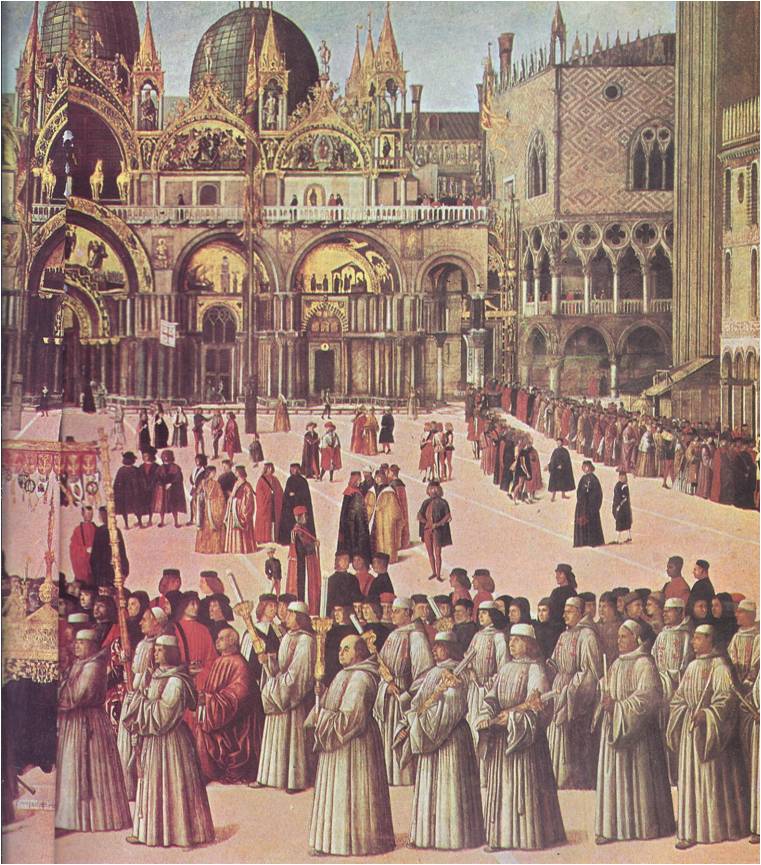

Comines saw all these things, but first the Venetian officials conducted him to the landing beside the palace of the doge, an architectural wonder whose upper walls of rose and pink marble perched on delicate, carved arches and slender columns. In the little square next to the palace stood two tall columns. On one was a statue of St. Theodore, the patron saint of Venice’s settlers; on the other, the bronze figure of the winged lion of St. Mark, the symbol of the city.

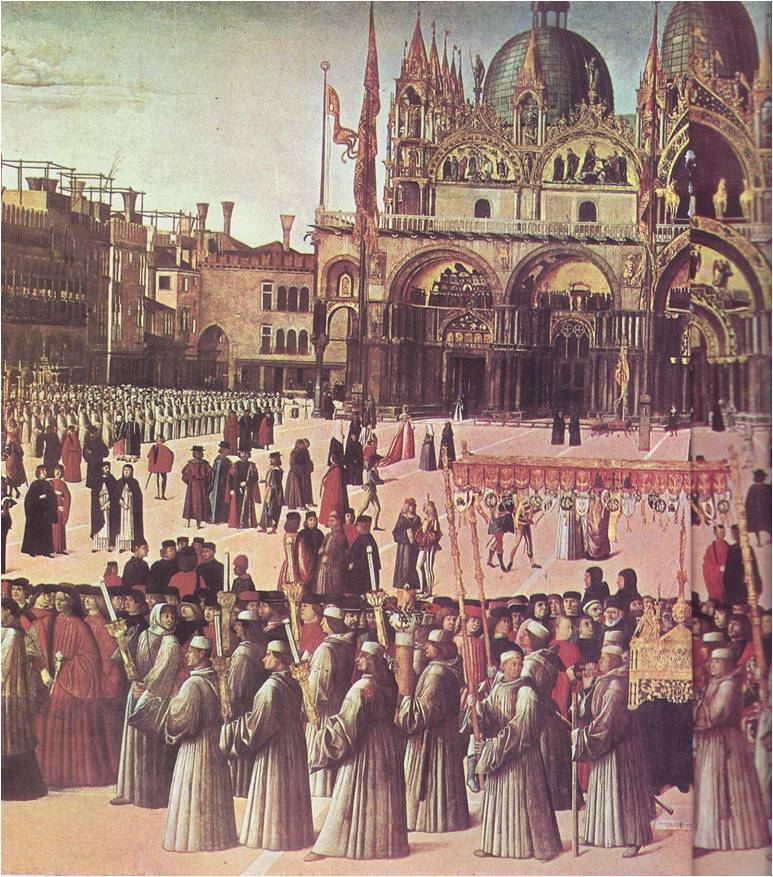

PIAZZA SAN MARCO

From the small square, the ambassador was led past the great campanile, or bell tower, into a vast square, the Piazza San Marco. The piazza was the centre of life in Venice. Here the doge, the senate and the guilds held their ceremonies and processions. Here, too, were rows of barbers’ and dentists’ shops and a noisy fish market just opposite the doge’s palace. Only Venetians could have sniffed without surprise the strangely mingled odours of incense and fish that filled the Piazza San Marco on holidays. Only Venetians could have built the gold-decked, five-domed Basilica of St. Mark that loomed above the square. In design and decoration, the church was a mixture of Eastern and European magnificence. Above its central doorways stood four Greek horses of bronze, which had been made in the time of Alexander the Great; the Venetians had “borrowed” them from Constantinople during a crusade.

The body of the city’s protector, St. Mark, which was said to be buried beneath the church, had also been “borrowed.” A group of Venetian adventurers had taken it from a ruined church in Egypt and smuggled it past the Moslem cargo inspectors in a load of pickled pork. The Moslems believed that pork was unclean and when the Venetians showed them their cargo, the inspectors held their noses and ran. So the story went and the Venetians had their artists paint pictures of it and labored to make the church that sheltered St. Mark as splendid as any in Christendom. Its outside walls glinted with mosaics set in gold. Inside, it was lofty and rich with color, a dazzling display of marble, mosaics, gold and gems. The huge altar screen, the work of Asian artists and Venetian goldsmiths, gleamed with enamel, gold and 6,000 jewels.

THE RIALTO

A dazzling show of a different kind could be seen at the Rialto‚ the business center of Venice. Along a stretch of the Grand Canal, the wharves were lined with merchant ships. Traders from every great city of Europe and the East crowded the docks and warehouses were piled high with the costly goods that Venice bought and sold. There were bolts of silk from Asia Minor and wool from Flanders, spices from Egypt and ivory from India, German copper, Spanish steel and Italian goblets of Bohemian silver. Beneath the porticoes of the Rialto sat the merchants of Venice, sharp-eyed men who traded goods and money, drove hard bargains and risked thousands of ducats each time they sent a galley to sea. On the wall behind the merchants’ tables was painted a map of their trade routes and on the stones of their parish church was written their code; “Let the merchant’s law be just, his weight true and his covenants faithful.”

Not all of the fine goods stacked in the warehouses came from foreign markets. Venetian craftsmen made many items that were highly prized in Flanders, France and England — finely wrought jewelry, steel armour and daggers with richly ornamented handles, carved wooden chests and graceful pewter cups. On the island called Burano, the women fashioned lace of a gauzy lightness to embellish the ball-gowns of queens or the ceremonial robes of bishops. On another island, Murano, glassmakers made goblets and lovely baubles of tinted glass so thin that all who saw them marveled. The method for making such glass was known only in Venice and any Murano craftsman who thought to make himself rich by taking the secret to some other city was discouraged by a strict law: “If a workman carry into another country any craft or art to the harm of the Venetian Republic, he will be ordered to return. If he disobeys, his nearest relatives will be imprisoned, so that concern for his family may persuade him to return. If he persists in his disobedience, secret measures will be taken to have him killed, wherever he may be.”

Venice believed in stern laws and in punishments that were swift and final. Though the city called itself a republic, the only citizens who could belong to its senate and the Maggior Consiglia, or Greater Council, were those men whose ancestors had been members of the Greater Council between the years 1172 and 1297. The names of these aristocrats were written in the Libro d’Oro, or Golden Book, and they — a thousand men or so — governed the city of more than a hundred thousand. Everything about life in Venice was strictly controlled by the government and the government was strictly controlled by the Council of Ten, officials who were elected by the senate but ruled with the power of dictators.

The doge, with all his pomp and splendour, had less freedom than most ordinary citizens. An aristocrat chosen to be doge could not refuse to serve. Once elected, he kept his office for life. He could not leave Venice, nor appoint the officials who served him, nor manage the finances of his own household. He and his sons were forbidden to marry unless the Greater Council approved and he could not resign without permission.

THE LION’S HEAD

Venice’s aristocrats all had as many duties as privileges. They wore their crimson togas to mark them as men of responsibility. They were expected to act as officers of the fleets, to risk their fortunes in trade and to serve Venice before they served their families or themselves.

Loyalty to Venice was the first duty of every Venetian, rich or poor. Merchants were expected to act as diplomats — and as spies — when they visited foreign ports. Citizens were asked to report their neighbours’ suspicious actions to the Council of Ten. Throughout the city there were boxes carved with lions’ heads. Letters of accusation slipped into the lions’ months brought immediate results. The accused man might simply disappear — into a dungeon where, eventually, he was quietly strangled. Sometimes a criminal would be found hanging by one foot from the palace of the doge, or pieces of his body would be discovered in different sections of the city. There were no public trials. The Council of Ten studied the evidence, listened to witnesses and passed judgment in secret.

It was an efficient system. With its strict controls, Venice was strong. It was a safe place to live and the city’s government never fell into the hands of one ambitious ruler or family. So Venice became a haven for men who were driven from their own towns by wars, tyrants and revolutions. Artists and scholars who fled to Venice often remained in the city when they could safely have gone home again. Venice was a good and pleasant place to be and it gave to men of genius the honour and riches that other cities gave to generals and princes.

RENAISSANCE VENICE

The art and learning of the Renaissance had come late to Venice, for the city had looked toward the East while the new age was developing in the West. When the Venetians did turn to the mainland, they gave all of their attention to conquest and trade. In the years of decline, the hardworking Venetians found that they had time to spare and gold to spend. They invested in comfort, beauty and pleasure. Wealthy merchants built great country houses on the mainland hills, where they could escape the heat and stench of the Venetian summer. Their favourite architect, Andrea Palladio, patterned his elegant villas after the finest ancient designs — and three hundred years later, the architects of England and America’s Virginia would pattern their houses after Palladio’s.

In town and country alike, the Venetians filled their homes with paintings, statues and books. By 1500, there were more than 200 printing presses in Venice. The finest books in the world were printed on the presses of Aldus Manutius, who opened his shop in 1490 and set out to gather together, edit and print all the known works of all the ancient Greek writers. Festina lente — “Make haste slowly”– was the motto printed on his books, which came to be called the Aldine Classics.

Most Venetians, however, were making haste to enjoy themselves. The city seemed to live in an endless carnival. Masquerading was its favourite sport. Companies of players and dancers performed in its theaters and poets spouted verse in its taverns. The choirmaster of St. Mark’s, Andrea Gabrieli, taught his choristers to sing in a new, more joyful way and the stern Council of Ten took a lively interest in festivals and pageants.

The government officials had always believed that art, pageantry and public displays were fine propaganda. The sailing of the Bucentaur on Ascension Day stirred up the patriotism and loyalty of the people in a way that no law or threat of punishment could do, so the Council made certain that there were many such lessons in loyalty during the year. The anniversary of a great Venetian victory, a saint’s day, the visit of a foreign prince or ambassador — any such occasion was celebrated with a procession or a festival.

PAINTING IN OILS

The councilmen also hired the finest artists to cover the walls of the doge’s palace and other public buildings with pictures of the celebrations and of the great events in Venice’s history. Then aristocrats, churchmen and guilds of merchants began to have their buildings decorated with pictures. Hospitals and charity schools, churches, palaces and even the walls of warehouses were covered with paintings.

The pictures were different from those that had been painted in any other part of Europe. About 1475, an Italian, Antonello da Messina, had learned the technique of oil painting from the Flemish painters of Burgundy. He had passed along his knowledge to Iacopo Bellini, the head of a family of talented painters. Soon every artist in Venice was experimenting with painting in oils. It was this that made their pictures seem to glow with light and gave Venetian paintings their special warmth.

Art was a part of everyday life for Venice and its people and the demand for paintings was so great that the workshops of popular artists were run almost like factories. A master‘s wife, sons, daughters, brothers, cousins, helpers and apprentices worked together in his studio. Hundreds of paintings were done and eager patrons clamoured for more.

Riches, fame and honour came to the great painters of Venice, masters such as the Bellini, Giorgione and Veronese. The king of painters was Titian. The Venetians called him Il Divino, the divine one. No one but Titian, they said, could paint human figures whose flesh so glowed with life. Certainly no one had painted so many religious pictures for the churches, gay pictures of goddesses and maidens for the walls of noblemen’s palaces, portraits of merchants, monarchs, duchesses and popes. The Venetians liked to say that the Emperor Charles V had bowed to their great artist. While Titian was painting the emperor’s portrait, he had dropped a brush and Charles had stooped to pick it up for him. Whether or not the story was true, Charles V did have Titian paint his portrait, gave him the titles of count and Knight of the Golden Spur and appointed him official court painter. The emperor also took Titian to Spain, but he could not persuade him to stay there, for the artist was much too happy with his life in Venice. He loved his palace overlooking the lagoon, his troop of students and the beautiful-girls of Venice and he loved the long, jovial evenings he spent with his friends Sansovino and Aretino. Venice called the three friends “the Triumvirate.” Titian, they said, was the first among artists, Sansovino was the first among architects and Aretino had the sharpest wit in Italy.

Sansovino had fled penniless from Rome when it was invaded and sacked by the emperor’s army of ruffians. In Venice, he was asked to design a series of splendid new buildings to replace the old market and the shops that edged the Piazza San Marco. He became so fond of the city that he refused to leave it when the pope asked him to return to Rome to be the architect of St. Peter’s.

Aretino was another of the many refugees from Rome. The son of a poor shoemaker, he had used his pen and his mocking wit to win himself a place in the courts of noblemen. He was called “the scourge of princes,” for he aimed his sharp wit at the great men of the world. His verses were so funny, his writing so popular and his fame so widespread that none of the men he made fools of dared to punish him. “I have struck terror into kings,” he boasted and it was true. In Rome, his mockery provoked the anger of Pope Clement and Aretino decided that it would be wise to take a trip to Venice. He stayed there for the rest of his life, writing merciless verses and sometimes solemn religious poems, growing rich, lavishing his money on the poor who flocked to his palace and trading stories with Sansovino and Titian.

THE KING OF PAINTERS

When Aretino died, in 1556, Sansovino and Titian went on working and enjoying themselves. The Venetians said that they were having a contest to see which would live and work the longest. Sansovino lost the competition, for he lived to be only eighty-five. Titian was as healthy as ever. At ninety, he painted a palace ceiling. At ninety-one, he decided to retire, but he lived to be ninety-nine and when death came he was at work on a picture for a Venetian church.

Now Venice turned to Tintoretto, a painter whom Titian had refused to teach. It was said that Titian was afraid the young artist would learn to paint too well. Indeed, when Tintoretto grew older, he did come close to matching Il Divino. In 1590, he delighted Venice by decorating a wall of the doge’s palace with the largest oil painting the world had ever seen. The Venetians called it the greatest of their paintings. It was also one of the last great paintings of the new age, which had now grown old.

The Venetian carnival was running down for lack of money — and for lack of spirit. Rich and contented, the Venetians had not joined the other sea powers in the race to the New World. More adventurous powers had found new routes to the luxuries of the East, routes which the Turks could not cut off and they had found wealth on the continents of America. France, England, the Netherlands and Spain ruled the trade routes and Venice was left far behind.

The Renaissance in Italy, that had first dawned in Florence, was coming to its close in Venice. The arts and learning that had found a place of refuge on the islands of the lagoon, now found new homes in the awakening countries of Western Europe. Venice grew sleepy and a little dull, the palaces that sat above the water seemed to doze, like sea-birds come to rest on a quiet bay.