In 1600, the Duke Virginio Orsini‚ nephew of the Medici ruler of Florence, arrived in England. He came to spend the New Year’s holidays and to see for himself the woman who fascinated all Europe. She was Elizabeth, queen of England and she was already a legend. To aristocratic travelers, such as the Duke Orsini, she was the most important tourist sight in England. Years later, she would still be as fascinating as any woman in history, for in her time — the Elizabethan Age — her country flourished as never before and the Renaissance blossomed in England. As a …

Read More »Tag Archives: Ariosto

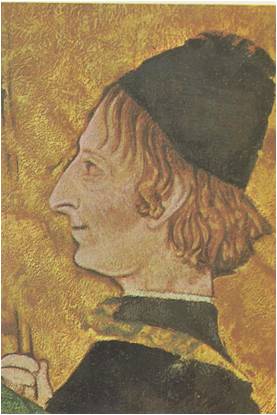

Gentlemen, Scholars and Princes 1400 – 1507

One day in the fifteenth century, the Turkish potentate of Babylonia decided to send gifts to the greatest ruler in Italy. He consulted his counselors and men who had traveled widely in Europe, asking them who best deserved this honour. They agreed that one Italian court outshone the rest and that his court must surely be the home of Italy’s mightiest sovereign. They did not name Milan, the home of the proud Sforza, nor Florence, the city of the clever Medici. The most magnificent court in Italy, they said, was at Ferrara, the capital of the dukes whose family name …

Read More »