The civilizations of India, China and the Moslem world progressed to about the year 1500 A.D., but what had been happening in western Europe in the centuries after Roman power began to decline and barbarian tribesmen had overrun the lands once part of the proud Roman Empire? What had taken the place of Roman might, government and law in western Europe? As Rome’s rule faded away, western Europe entered a period known as the Middle Ages or the medieval period. For a long time there was neither a single empire nor nations as we know them to day. Central governments, …

Read More »Tag Archives: Charlemagne

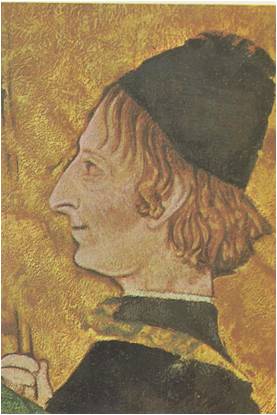

The Thirty Years War 1618 – 1625

EMPEROR MAXIMILIAN I of the Holy Roman Empire walked up to a wild lion and pulled out its tongue; his enemies set his house on fire, tried to poison him and ambushed him twenty times; wild bears attacked him three times, stupid servants ignited powder kegs near him and five boats capsized under him, but always he escaped unharmed. He was a greater general than Julius Caesar, a brilliant musician, scholar and inventor. All these stories were proof that Maximilian was a great hero — but they were written by authors whom Maximilian himself hired to do the job. He …

Read More »Gentlemen, Scholars and Princes 1400 – 1507

One day in the fifteenth century, the Turkish potentate of Babylonia decided to send gifts to the greatest ruler in Italy. He consulted his counselors and men who had traveled widely in Europe, asking them who best deserved this honour. They agreed that one Italian court outshone the rest and that his court must surely be the home of Italy’s mightiest sovereign. They did not name Milan, the home of the proud Sforza, nor Florence, the city of the clever Medici. The most magnificent court in Italy, they said, was at Ferrara, the capital of the dukes whose family name …

Read More »The Conquest of England 1066-1265

IN THE DIM LIGHT of early morning, the Frenchmen were preparing for battle. Squires helped the knights put on their armour, grooms brought up the horses‚ archers tested their bows, foot soldiers began to assemble, while mounted messengers hurried busily here and there. The date was October 14, 1066 and before the sun set that day a kingdom would change hands and a new era in English history would begin. The battle, one of the most decisive ever fought, would be known as the Battle of Hastings. The cause of the battle was ambition — the driving ambition of Duke …

Read More »Feudal France 814-1314

AFTER THE BREAKUP OF CHARLEMAGNE’S Empire, France, the western half of the empire, was ruled by a series of weak kings. They were so weak that they were known as the “do-nothing kings,” and indeed, they could do nothing to stop their powerful and greedy nobles from fighting among themselves. Finally the Carolingian line came to an end and the Franks, as the French were then called, elected a new king. He was Hugh Capet, a relative of the famous Count Odo who had directed the defense of Paris against the Vikings. With Hugh began the line of Capetian kings …

Read More »The Castle, the Manor and the Knight 900-1300

COUNT LEON, lord of the vast domain of Grandpré, stirred and waved away his servants. As he opened his eyes, the first rays of the sun were slanting through the narrow windows of his bedchamber. He stared sleepily at the tapestry hanging on the thick stone wall. It depicted a stag hunt and he enjoyed looking at it, for there were few things in the world he loved more than hunting. For a few minutes he lay there, listening to the sounds drifting up from the courtyard –the clop of horses’ hoofs‚ the creak of leather, the clatter of boots …

Read More »Fury from the North 814-1042

“. . FROM THE FURY OF THE NORTHMEN, Good Lord, deliver us.” Until recent times, this line was included in the prayer book used by the Church of England. The raids of the Norse Vikings on Britain were so terrible that the victims never forgot them. For generations the memory of the savage Norsemen was kept alive and Englishmen repeated this prayer for more than a thousand years. It was not only Britain that felt the fury of the Norsemen; they raided the European continent as well. The Norsemen’s ships themselves seemed to threaten terror. The hull of a Viking …

Read More »The Abbasids: Glory and Decay 750 -1258 A. D.

UNDER THE Omayyads, who ruled from 661 to 750, Islam had grown into a mighty empire. Arabic had become its language, while the Arabs, in turn, had picked up useful skills from the peoples they had conquered. The state had grown rich from the tribute paid by non-Moslems and the land tax paid by landowners. Though the caliphs were mainly concerned with pleasure and power, they had not neglected religion completely. They had built the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem and the Omayyad Mosque in Damascus — two magnificent sanctuaries which were the holiest places in Islam after the …

Read More »The Church and the Empire A.D. 527-1261

CHRISTIANITY, as the official religion of Byzantium‚ was under the control of the government. The emperor was the head of both church and state and high church officials in the East recognized him as the religious leader of the land. One of them wrote, “Nothing should happen in the Church against the command or will of the Emperor.” The church organization was similar to that of the state. As its head, but under the emperor, was the patriarch of Constantinople, who was appointed by the emperor. The appointment had to be approved by high church officials, but actually they never …

Read More »