There he sat in the great hall in the German city of Worms. His bright eyes and wide forehead gave him an air of distinction. You would not quickly forget that face. Before him was gathered an assembly of high ranking nobles and churchmen from many parts of Europe. For this man was Charles V, Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, Archduke of Austria, ruler of the Netherlands and half of Italy, as well as King of Spain and master of Spain’s vast possessions in the New World. Yet Charles, who belonged to the famous Hapsburg family of Austria, was …

Read More »Tag Archives: Charles V

France Becomes a Great Nation 1453-1631

WHEN MORE than a century of war between England and France ended in 1453, it was the French king, Charles VII, who was victorious. Although he had driven the English out of France, Charles found himself the king of a sad land. During the wars the great French nobles had fought among themselves as bitterly as they had fought the English and they had become so powerful that they no longer respected their king. France itself was devastated, the people poor and hungry. Paris had been half ruined. Wolves prowled the city by night and twenty-four thousand houses stood empty. …

Read More »Adventures in the New World 1519 – 1620

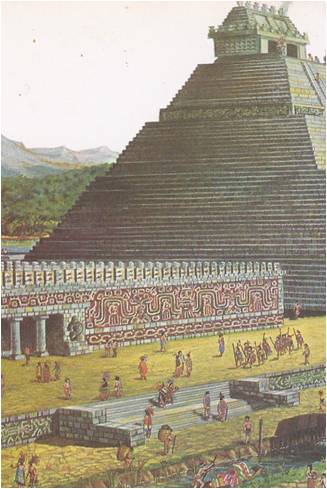

“I DID NOT come to till the soil like a peasant,” said Hernando Cortez. “I came to find gold.” His words echoed the thoughts of almost every Spaniard in the New World. The discovery of the sea route to the West had set off a great treasure hunt. Colonizing and slaughtering, building and plundering, the gold-hungry Spaniards won a Spanish Empire of the West. Conquistadores‚ they were called — the conquerors. None of the treasure-hunters was more cunning or ambitious than Hernando Cortez‚ who came to the island of Hispaniola in 1504. It was not until 1519 that the governor …

Read More »The Counter Reformation 1521-1648

THE BLAST OF MUSKETS and the clang of swords against armour echoed across the plains of Italy, Spain and the Lowlands. Warriors of the king of France were clashing with the Spanish infantry and German knights of the Holy Roman Emperor. Control of the nations of Europe was the prize both nations sought. They schemed and plotted; their generals planned campaigns; their soldiers marched out to victory or defeat. Victories counted for little, for much of Europe’s future was decided by another, different kind of war – a war for the minds and souls of men. Village squares and royal …

Read More »The Monk from Wittenberg 1505-1546

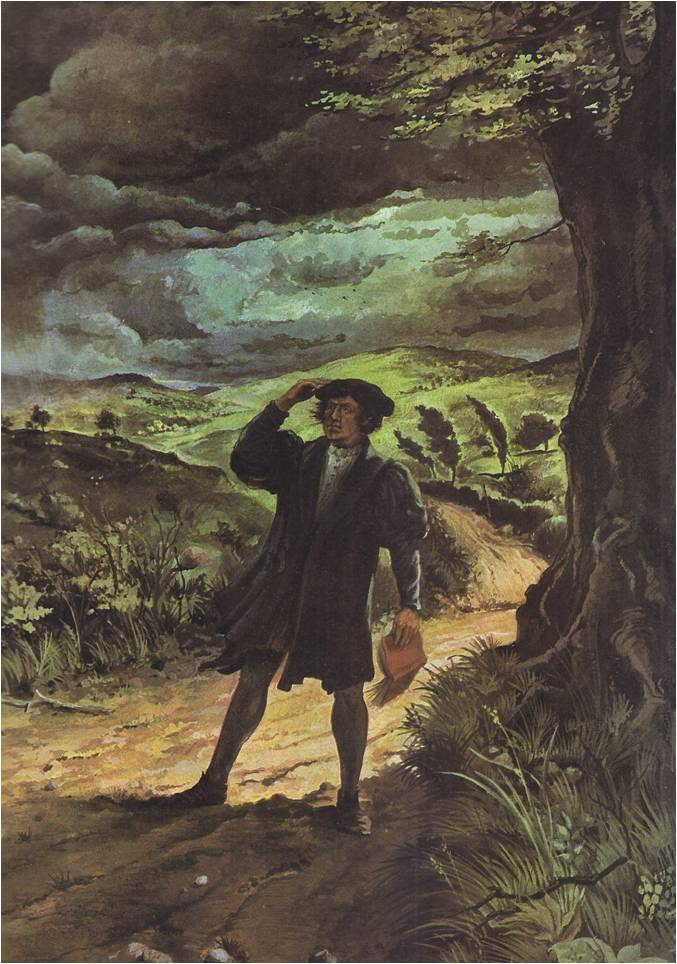

ON A SULTRY JULY DAY IN 1505, a young law student, Martin Luther, was walking along a country road in Germany when a summer storm blew up. The air grew heavy and black clouds filled the sky. Before Luther could take shelter, thunder began to crash. A bolt of lightning struck the road almost at his feet. Thrown to the ground, he lay shaking, not certain whether he was alive or dead. “Help me, Saint Anne,” he cried, “help me and I will become a monk.” After a moment, Luther’s trembling stopped. He stood up, found that he was not …

Read More »The Renaissance in the North and Spain 1400 – 1598

Through the bustling market-towns of the Low Countries passed the traders, goods and gold of all Europe. Here the luxuries of Asia — spices‚ silks, jewels and perfumes — were exchanged for the practical products of the North — woolen cloth and utensils of iron and copper and wood. In shops and inns, wily Italian shippers and bankers bargained with the solemn, solid merchants from Germany and Flanders — and made the profits that built the Renaissance cities of Italy. In tall-spired cathedrals, in palaces, guildhalls and universities, wandering Italian artists discovered works of art and scholarship as great as …

Read More »Rome, the City of the Pope 1492-1564

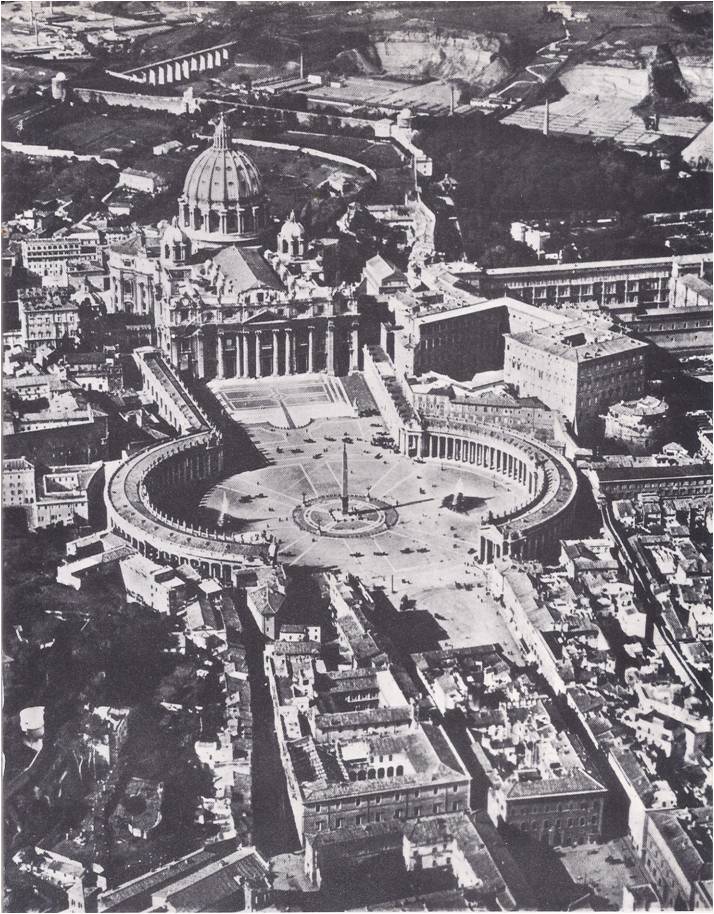

In 1492, young Giovanni de’ Medici bade farewell to his father, Lorenzo the Magnificent and left Florence to take his place in Rome among the cardinals of the church. At sixteen, Giovanni was a nobleman in the court of the pope, a man of influence and power. That was fortunate, for when Giovanni was eighteen, his family’s power collapsed. The Florentines drove the Medici from their city and Giovanni, who had come home for a visit, narrowly escaped being stoned by the citizens who once had cheered him. As he crept out of the city, disguised as a poor friar, …

Read More »The Hundred Years War 1326-1477

THE LONG STRUGGLE between France and England, known to history as the Hundred Years’ War, was not really a war — and it lasted more than a hundred years. Rather than a war, it was a series of separate battles, with periods of uneasy peace between and it lasted from 1338 to 1453. It was time of misery for both sides, but the French lost more men and saw much of their land devastated. By the end of the Hundred Years’ War, important changes had taken place in both countries. In France, the years of conflict weakened the power of …

Read More »