If you had been a citizen of the ancient Greek city of Athens on a fine spring morning in 409 B.C., you would have gathered with thousands of your fellow citizens on a hillside inside the city. You would then have listened carefully to the discussion of various matters of business, conducted by the chairman and secretary of the meeting from a platform below and facing you. You would have seen an Athenian citizen thread his way from the hillside to this platform. This was a sure sign that he had a proposal to make to the voters. The citizen …

Read More »Tag Archives: city-state

Kings, Tyrants and Democracy 1000 B. C. to 100 B. C.

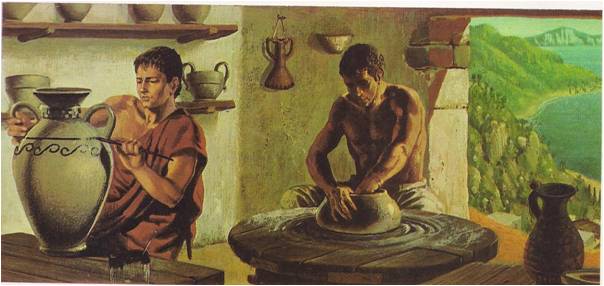

During the Dark Ages, the large kingdoms of Homer’s Achaean heroes had disappeared. The Greek world was now dotted with dozens of little countries. They had begun with fortresses set on hills and crags. Soon each fortress was surrounded by a village, as farmers abandoned their huts in the fields and built new homes close to the walls. In times of danger, they could take refuge behind the walls. A market place was built and a few metalsmiths and potters opened shops. When temples were set up inside the fortress, the castle hill became an acropolis, a “high town,” the …

Read More »