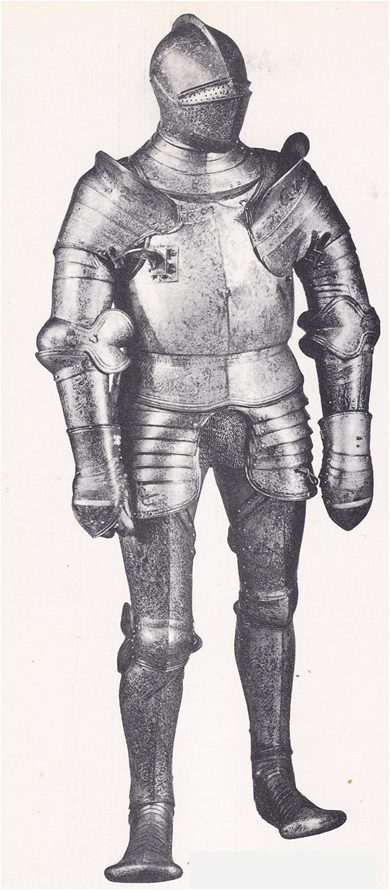

Milan’s most important business street had no displays of velvet cloaks, bright bolts of silk, or cloth-of-gold. It was a dusty, smoky street, made hot by the fires of forges and filled with the din of hammers shaping steel — the Street of the Armourers. Milan made the finest armour in the world. In the Middle Ages, the crusaders came there for chain mail and it was said that entire armies were outfitted in a few days. Later, the fashions of war changed. Knights wore heavy suits of jointed steel plates that covered them from head to toe and elegant …

Read More »Tag Archives: condottieri

The Sound of Bells and Trumpets in Europe 1300 – 1600

Bells and trumpets sounded across Europe in the time that men would call the Middle Ages. Knights in glistening armour rode forth to serve God and their kings; life was like a stately procession winding through a landscape marked by castles and cathedrals. Each man knew his place. He was a prince, a knight, a squire, a priest, a craftsman, or a serf. He wore the clothes that belonged to his rank — the armour and family emblems of a nobleman, the robes of a churchman, or the rough wool jerkin of a serf. He lived according to an age-old …

Read More »