If you had been a citizen of the ancient Greek city of Athens on a fine spring morning in 409 B.C., you would have gathered with thousands of your fellow citizens on a hillside inside the city. You would then have listened carefully to the discussion of various matters of business, conducted by the chairman and secretary of the meeting from a platform below and facing you. You would have seen an Athenian citizen thread his way from the hillside to this platform. This was a sure sign that he had a proposal to make to the voters. The citizen …

Read More »Tag Archives: Demosthenes

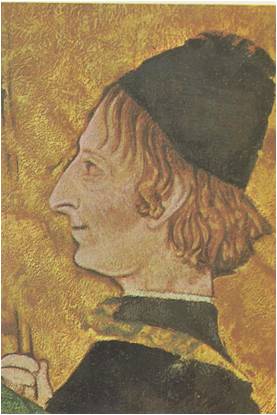

Gentlemen, Scholars and Princes 1400 – 1507

One day in the fifteenth century, the Turkish potentate of Babylonia decided to send gifts to the greatest ruler in Italy. He consulted his counselors and men who had traveled widely in Europe, asking them who best deserved this honour. They agreed that one Italian court outshone the rest and that his court must surely be the home of Italy’s mightiest sovereign. They did not name Milan, the home of the proud Sforza, nor Florence, the city of the clever Medici. The most magnificent court in Italy, they said, was at Ferrara, the capital of the dukes whose family name …

Read More »Greece and the World 323 B. C. – 250 B. C.

In the last years of the fourth century B. C., Greek citizens going about their business in the stoas or the shops sometimes stopped and wondered what was wrong. Everything seems strange. They themselves had not changed and their cities looked the same as before, but the world around them was so different that they could hardly recognize themselves. The little poleis on the mainland looked out at an enormous empire, which stretched across Asia and Egypt. They shipped their olive oil and pottery across the Mediterranean. Their corn came from fields beside the Black Sea and the Nile. Merchants …

Read More »The Conquerors 343 B. C. – 323 B. C.

In 343 B. C., the philosopher Aristotle left the quiet of his study and journeyed to Macedonia, a country in the mountain wilderness north of Greece. He had been hired to tutor the rowdy young son of a king. The boy, Alexander, was a yellow-haired thirteen-year-old. His manners were polite and he seemed to be clever enough, but he was wild. It was hard for him to pay attention to his studies. He much preferred galloping across the fields on his huge horse. He proudly told his new tutor that he had tamed the horse himself. When he did come …

Read More »