The execution of the king stunned the rulers of Europe. They were stunned as well by the French military victories in Belgium and along the Rhine River. Furthermore, the French government was offering to come to the aid of any people willing to fight for their liberty. The revolution threatened to spill over into other countries, becoming a crusade of peoples against kings and nobility. If successful, it could destroy every kingdom in Europe. England and most of the European powers, therefore, joined together in 1793 to crash the revolution and to place another king on the throne of France. …

Read More »Tag Archives: Estates-General

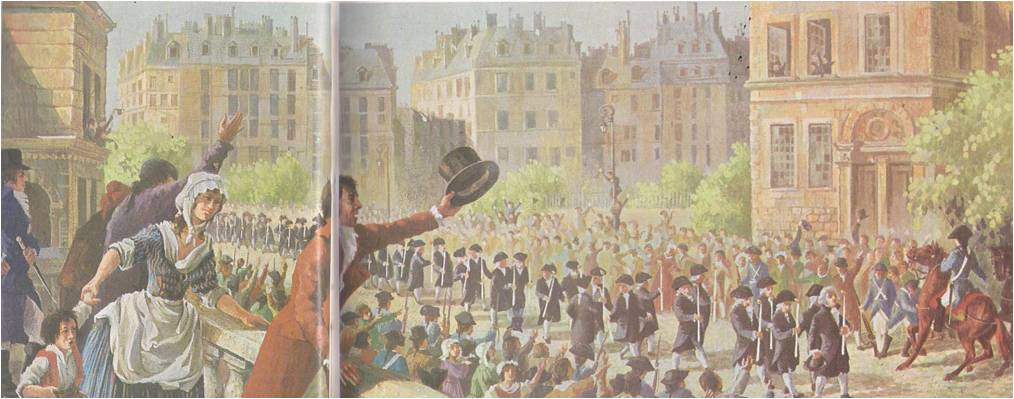

“The King to Paris!” 1789

In the towns and cities of the provinces, the news of the fall of the Bastille led to wild celebrations and a series of revolts against local governments. These governments had long been unpopular, since most of them were controlled by nobles and others who had bought their government positions from the king. The town people set up new governments, similar to the one in Paris and organized local units of the National Guard. The revolution spread to the countryside as well. There the peasant uprising had started even before the fall of the Bastille. The peasants made up at …

Read More »The Voice of the People 1789

The sun had broken through the clouds after a night of spring showers. Dripping leaves sparkled in the golden light, which flooded the gaily decorated streets of Versailles and the broad terraces of the king’s royal palace. It was May 4, 1789, the day of the opening ceremony of the recently elected Estates General. The streets were crowded with visitors, most of them from Paris, only a few miles away. They had come to see the grand procession of the Estates General and were in a holiday mood. The shops were closed. Local citizens watched from windows, crowded balconies and …

Read More »The French Revolution – Champion of Liberty 1782 – 1789

WHEN THE MARQUIS DE LAFAYETTE returned to France in 1782, after taking part in the American Revolution, he was hailed as a popular hero. It was pleasant to be welcomed as a champion of liberty, but he had been in America so long that he was beginning to see his own country as an American might see it and he was troubled. France was one of the largest and richest countries in Europe and yet the wealth of the nation was in the hands of a few, while the great majority of the people had almost nothing. He found a …

Read More »Feudal France 814-1314

AFTER THE BREAKUP OF CHARLEMAGNE’S Empire, France, the western half of the empire, was ruled by a series of weak kings. They were so weak that they were known as the “do-nothing kings,” and indeed, they could do nothing to stop their powerful and greedy nobles from fighting among themselves. Finally the Carolingian line came to an end and the Franks, as the French were then called, elected a new king. He was Hugh Capet, a relative of the famous Count Odo who had directed the defense of Paris against the Vikings. With Hugh began the line of Capetian kings …

Read More »