One day in the fifteenth century, the Turkish potentate of Babylonia decided to send gifts to the greatest ruler in Italy. He consulted his counselors and men who had traveled widely in Europe, asking them who best deserved this honour. They agreed that one Italian court outshone the rest and that his court must surely be the home of Italy’s mightiest sovereign. They did not name Milan, the home of the proud Sforza, nor Florence, the city of the clever Medici. The most magnificent court in Italy, they said, was at Ferrara, the capital of the dukes whose family name …

Read More »Tag Archives: Ferrara

Florence in the Golden Age 1469 -1498

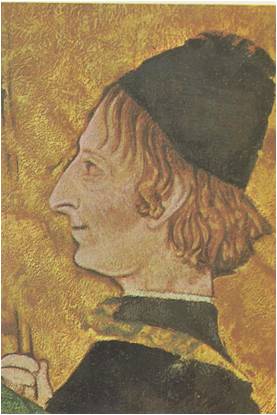

Lorenzo de’ Medici was far from handsome. His skin was sallow, his eyes had a short-sighted squint and his nose was flat and wide. His voice was high and thin. Like every man in his family, he had the gout. Yet there was grandeur in everything Lorenzo did. He loved art and books, music and poetry and women. He delighted in sports, hunting and galloping across the brown Tuscan hills. He dealt with ambassadors like a prince, his palace was the gathering-place for the great men of Italy and his city won renown for both its scholars and its carnivals. …

Read More »The Sound of Bells and Trumpets in Europe 1300 – 1600

Bells and trumpets sounded across Europe in the time that men would call the Middle Ages. Knights in glistening armour rode forth to serve God and their kings; life was like a stately procession winding through a landscape marked by castles and cathedrals. Each man knew his place. He was a prince, a knight, a squire, a priest, a craftsman, or a serf. He wore the clothes that belonged to his rank — the armour and family emblems of a nobleman, the robes of a churchman, or the rough wool jerkin of a serf. He lived according to an age-old …

Read More »