IN 1518, AN INDULGENCE PEDDLER, a priest from France, made his way through one of the twisting Alpine passes that led into Switzerland. He carried with him a supply of bright banners, an impressive-looking copy of Pope Leo’s Declaration of Indulgences and of course, a collecting box. The French priest’s hopes were high, for the little Swiss merchant towns were rich. He did indeed do well at first and his collecting box began to grow heavy with pieces of gold. Then he came to the town of Zurich. As he began to set up his banners, a town official stopped …

Read More »Tag Archives: France

The Monk from Wittenberg 1505-1546

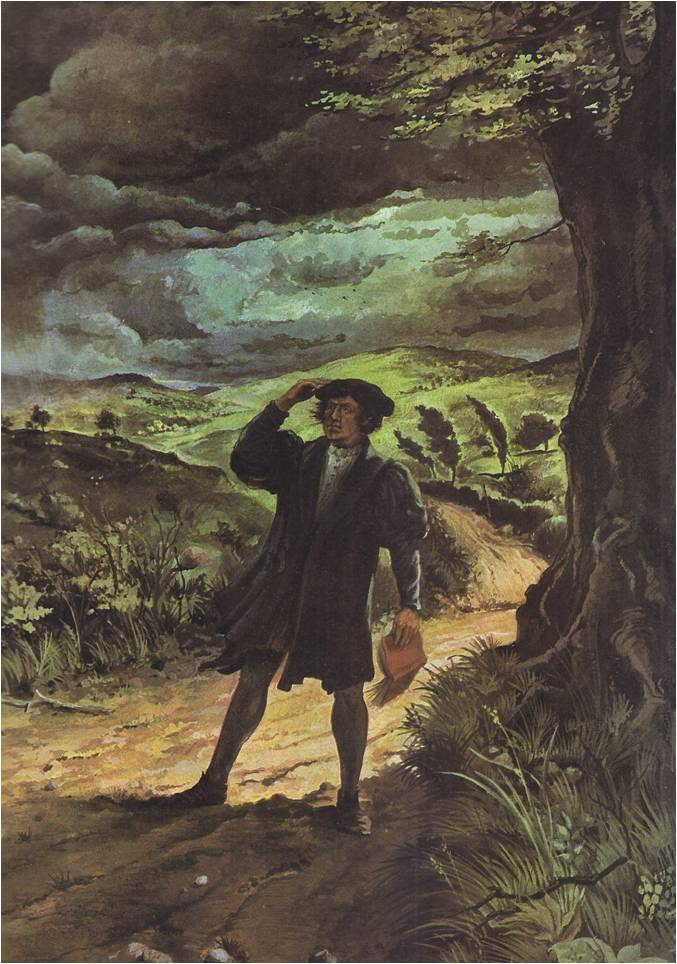

ON A SULTRY JULY DAY IN 1505, a young law student, Martin Luther, was walking along a country road in Germany when a summer storm blew up. The air grew heavy and black clouds filled the sky. Before Luther could take shelter, thunder began to crash. A bolt of lightning struck the road almost at his feet. Thrown to the ground, he lay shaking, not certain whether he was alive or dead. “Help me, Saint Anne,” he cried, “help me and I will become a monk.” After a moment, Luther’s trembling stopped. He stood up, found that he was not …

Read More »England’s Elizabeth: Queen of Words and Music 1511 – 1603

In 1600, the Duke Virginio Orsini‚ nephew of the Medici ruler of Florence, arrived in England. He came to spend the New Year’s holidays and to see for himself the woman who fascinated all Europe. She was Elizabeth, queen of England and she was already a legend. To aristocratic travelers, such as the Duke Orsini, she was the most important tourist sight in England. Years later, she would still be as fascinating as any woman in history, for in her time — the Elizabethan Age — her country flourished as never before and the Renaissance blossomed in England. As a …

Read More »The Italian Kings of France 1494 – 1590

In all Europe there was no greater admirer of Italy than Francis I, king of France. Francis practiced Italian manners in his court, built Italian palaces in his parks and kept Italian books in his library. He collected Italian paintings and the artists who painted them. Indeed, the king admired Italy so much that he wanted to conquer it all. Francis was not the first ruler to feel these strong Italian longings. In England, Spain and Germany, kings and princes were busily remodeling their courts, their castles and themselves in the Italian manner. Though the little states of Italy were …

Read More »Venice, City in the Sea 1350 – 1590

The houses of Venice are “like sea-birds half on sea and half on land,” said Cassiodorus. An officer of a king of the Goths, Cassiodorus saw Venice in 537. It was a little settlement of huts built on the mud-flats in an out-of-the-way lagoon. Its people were refugees‚ Italians who had been driven from their homes by a horde of barbaric invaders. They were safe in the lagoon, for no stranger could navigate the treacherous channels. For the sake of safety, they were content with comforts that were simple at best. “In this place,” Cassiodorus said, “rich and poor are …

Read More »Florence in the Golden Age 1469 -1498

Lorenzo de’ Medici was far from handsome. His skin was sallow, his eyes had a short-sighted squint and his nose was flat and wide. His voice was high and thin. Like every man in his family, he had the gout. Yet there was grandeur in everything Lorenzo did. He loved art and books, music and poetry and women. He delighted in sports, hunting and galloping across the brown Tuscan hills. He dealt with ambassadors like a prince, his palace was the gathering-place for the great men of Italy and his city won renown for both its scholars and its carnivals. …

Read More »Florence, First City of the Renaissance 1200-1480

March 25, 1436, was the Feast of the Annunciation and the city of Florence was decked out for a celebration. Banners flew everywhere, ribbons and garlands of flowers decorated the houses and draperies of cloth-of-gold were looped across the shop-fronts. The city bustled with excitement, for on this Annunciation Day the pope was to dedicate the Duomo, the wonderful new Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore, then the largest church in the world. At dawn, the people began to fill the streets. They crowded around the high wooden walk that led to the cathedral from the monastery where the pope …

Read More »The Hundred Years War 1326-1477

THE LONG STRUGGLE between France and England, known to history as the Hundred Years’ War, was not really a war — and it lasted more than a hundred years. Rather than a war, it was a series of separate battles, with periods of uneasy peace between and it lasted from 1338 to 1453. It was time of misery for both sides, but the French lost more men and saw much of their land devastated. By the end of the Hundred Years’ War, important changes had taken place in both countries. In France, the years of conflict weakened the power of …

Read More »The Town and the Guild 1100 -1382

ONE FINE SPRING MORNING, in the French town of Troyes, in the county of Champagne, a bell rang out through the clear air. The people streaming along the road to the town knew why the bell was ringing; it signaled the start of another day of the fair. Now they walked faster or whipped up their horses, anxious not to miss any of the excitement. Most of them were merchants, who had come to buy the goods that were on display. Some were lords and ladies, who hoped to find gleaming silks from the Orient, or fine Spanish leather, or …

Read More »The Crusades 1096-1260

ON A COLD NOVEMBER DAY IN 1096, a great crowd of people gathered in a field at the town of Clermont in France. They had come from miles around and near them were pitched the tents they had put up for shelter. For some days, Pope Urban II had been holding a great council of cardinals, bishops and princes. Today he was to speak to the people and so many wanted to hear that no building was large enough to hold them all. A platform had been built in the center of the field and as Pope Urban stepped up …

Read More »