One day in the fifteenth century, the Turkish potentate of Babylonia decided to send gifts to the greatest ruler in Italy. He consulted his counselors and men who had traveled widely in Europe, asking them who best deserved this honour. They agreed that one Italian court outshone the rest and that his court must surely be the home of Italy’s mightiest sovereign. They did not name Milan, the home of the proud Sforza, nor Florence, the city of the clever Medici. The most magnificent court in Italy, they said, was at Ferrara, the capital of the dukes whose family name …

Read More »Tag Archives: Homer

Byzantine Glory A.D. 610-1057

The period from 610 to 717 was one of the darkest in Byzantine history. During that time, the edges of the empire crumbled under the pressure of powerful enemies. A people from northern Italy, the Lombards, conquered more than half of Italy. In central Arabia, the Arab tribes had joined together under the religion of Mohammed and marched against their neighbors. They took the kingdom of Persia, invaded Palestine and in 658 captured Jerusalem. The conquering Moslems, as the followers of Mohammed were called, swept on and soon took over Syria and Egypt. They marched along the northern shore of …

Read More »The City of Augustus 29 B. C. – A. D. 14

IN 29 B.C. the gates of war were closed. Rome was at peace. Senators and the people of the mob-men who had hated and fought each other through long, bitter years — stood side by side in the Forum while the great doors of the temple of Janus were slowly pushed shut. That had happened only twice before in the history of the city. The crowd in the Forum cheered the peace and they cheered Octavius, their new ruler. He was no longer the young man who had rushed to Rome after the murder of his uncle, Caesar. Seventeen years …

Read More »Greece and the World 323 B. C. – 250 B. C.

In the last years of the fourth century B. C., Greek citizens going about their business in the stoas or the shops sometimes stopped and wondered what was wrong. Everything seems strange. They themselves had not changed and their cities looked the same as before, but the world around them was so different that they could hardly recognize themselves. The little poleis on the mainland looked out at an enormous empire, which stretched across Asia and Egypt. They shipped their olive oil and pottery across the Mediterranean. Their corn came from fields beside the Black Sea and the Nile. Merchants …

Read More »The Conquerors 343 B. C. – 323 B. C.

In 343 B. C., the philosopher Aristotle left the quiet of his study and journeyed to Macedonia, a country in the mountain wilderness north of Greece. He had been hired to tutor the rowdy young son of a king. The boy, Alexander, was a yellow-haired thirteen-year-old. His manners were polite and he seemed to be clever enough, but he was wild. It was hard for him to pay attention to his studies. He much preferred galloping across the fields on his huge horse. He proudly told his new tutor that he had tamed the horse himself. When he did come …

Read More »Athens: City of Wisdom and War 700 B. C. to 500 B. C.

Of all the city-states in Greece, Athens was the most fortunate. The city’s guardian was Athena, the goddess of war and wisdom. Indeed, the Athenians did well in war and were blessed with wisdom. In the dark days, when barbaric invaders had conquered one city after another, Athens had not surrendered. Later, when Athens felt the growing pains that brought civil war and ruin to so many city-states, a series of wise men guided Athenians safely through their troubles. The right leaders always seemed to come along at the right time. It was more than good luck, ofcourse. The Athenians …

Read More »Kings, Tyrants and Democracy 1000 B. C. to 100 B. C.

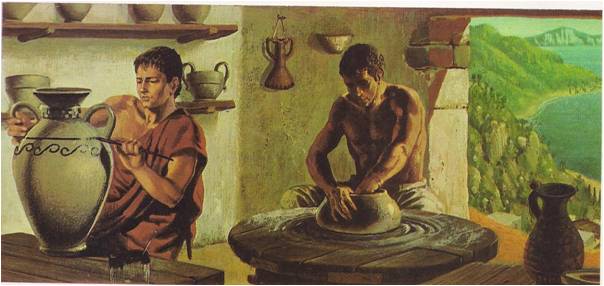

During the Dark Ages, the large kingdoms of Homer’s Achaean heroes had disappeared. The Greek world was now dotted with dozens of little countries. They had begun with fortresses set on hills and crags. Soon each fortress was surrounded by a village, as farmers abandoned their huts in the fields and built new homes close to the walls. In times of danger, they could take refuge behind the walls. A market place was built and a few metalsmiths and potters opened shops. When temples were set up inside the fortress, the castle hill became an acropolis, a “high town,” the …

Read More »Gods and Heroes 800 B.C. – 550 B.C.

From island to island and town to town, across the wide new world of the Greeks, the minstrel wandered, with a harp slung across his back and a batch of stories in his hand. When he knocked at the gate of a palace or great house and offered to sing for his supper, he was never refused. There were no shows to see and no books to read. The people relied on the minstrels to entertain them and to tell their stories of the past, which otherwise might be forgotten. The minstrel’s stock of stories was a mixture of tall …

Read More »