The execution of the king stunned the rulers of Europe. They were stunned as well by the French military victories in Belgium and along the Rhine River. Furthermore, the French government was offering to come to the aid of any people willing to fight for their liberty. The revolution threatened to spill over into other countries, becoming a crusade of peoples against kings and nobility. If successful, it could destroy every kingdom in Europe. England and most of the European powers, therefore, joined together in 1793 to crash the revolution and to place another king on the throne of France. …

Read More »Tag Archives: Paris

The Fall of King Louis 1789-1793

“Down with the King!” That cry was heard again and again on the night of August 9, 1792, as restless mobs gathered in the streets of Paris. They had only one purpose in mind and that was to make certain the king was toppled from his throne. The Assembly had been warned to dispose of the king before midnight and that deadline was only hours away. If the Assembly failed to act, the mobs would join forces, march on the royal Palace and seize the king themselves. As the midnight deadline approached, the frightened members of the Assembly were still …

Read More »“The King to Paris!” 1789

In the towns and cities of the provinces, the news of the fall of the Bastille led to wild celebrations and a series of revolts against local governments. These governments had long been unpopular, since most of them were controlled by nobles and others who had bought their government positions from the king. The town people set up new governments, similar to the one in Paris and organized local units of the National Guard. The revolution spread to the countryside as well. There the peasant uprising had started even before the fall of the Bastille. The peasants made up at …

Read More »The Fall of the Bastille 1789

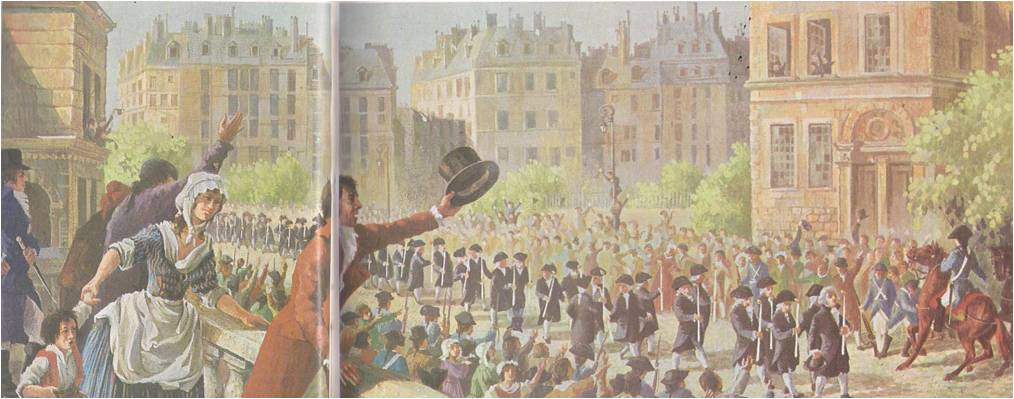

On Sunday, July 12, 1789, the people of Paris learned that Necker, the popular minister, had suddenly been dismissed by the king. They could only guess at the king’s reasons for wanting Necker out of the way. It seemed clear enough that Necker’s dismissal had something to do with the recent arrival of Swiss and German troops in the Paris area. It was said that more troops were arriving every day. Why? People were almost afraid to guess at the answer. The news of Necker spread quickly and angry crowds gathered in the streets. A young man named Desmoulins leaped …

Read More »The Voice of the People 1789

The sun had broken through the clouds after a night of spring showers. Dripping leaves sparkled in the golden light, which flooded the gaily decorated streets of Versailles and the broad terraces of the king’s royal palace. It was May 4, 1789, the day of the opening ceremony of the recently elected Estates General. The streets were crowded with visitors, most of them from Paris, only a few miles away. They had come to see the grand procession of the Estates General and were in a holiday mood. The shops were closed. Local citizens watched from windows, crowded balconies and …

Read More »Florence in the Golden Age 1469 -1498

Lorenzo de’ Medici was far from handsome. His skin was sallow, his eyes had a short-sighted squint and his nose was flat and wide. His voice was high and thin. Like every man in his family, he had the gout. Yet there was grandeur in everything Lorenzo did. He loved art and books, music and poetry and women. He delighted in sports, hunting and galloping across the brown Tuscan hills. He dealt with ambassadors like a prince, his palace was the gathering-place for the great men of Italy and his city won renown for both its scholars and its carnivals. …

Read More »The Town and the Guild 1100 -1382

ONE FINE SPRING MORNING, in the French town of Troyes, in the county of Champagne, a bell rang out through the clear air. The people streaming along the road to the town knew why the bell was ringing; it signaled the start of another day of the fair. Now they walked faster or whipped up their horses, anxious not to miss any of the excitement. Most of them were merchants, who had come to buy the goods that were on display. Some were lords and ladies, who hoped to find gleaming silks from the Orient, or fine Spanish leather, or …

Read More »The Power of the Church 529 – 1409

IN THE YEAR 1134, in the town of Chartres in France, the church burned down. The church was a cathedral — that is, it was the church of a bishop. The bishop at that time was Theodoric and he immediately began the construction of another cathedral. He knew that the task would not be an easy one; it meant raising large sums of money and finding many workmen and the actual work of building would take years. Bishop Theodoric allowed nothing to stop him, he won the support of the people, of commoners and nobles alike. An eye-witness, who visited …

Read More »Feudal France 814-1314

AFTER THE BREAKUP OF CHARLEMAGNE’S Empire, France, the western half of the empire, was ruled by a series of weak kings. They were so weak that they were known as the “do-nothing kings,” and indeed, they could do nothing to stop their powerful and greedy nobles from fighting among themselves. Finally the Carolingian line came to an end and the Franks, as the French were then called, elected a new king. He was Hugh Capet, a relative of the famous Count Odo who had directed the defense of Paris against the Vikings. With Hugh began the line of Capetian kings …

Read More »