Today we speak the words, “I am a World citizen,” with pride. To the people of the ancient world the statement, “I am a Roman citizen,” was a badge of high honour. Beginning as a small city state in Italy, Rome grew into a vigorous republic and finally into an empire so mighty that it included the whole of the Mediterranean world. Even after Rome’s grandeur had waned, its influence lived on among later peoples. Rome’s history is a reminder that the destiny of a nation rests more on the wisdom of its leaders and the character of its people …

Read More »Tag Archives: Pompey

The First Palm Sunday A.D. 29

IT WAS the Sunday before Passover. The soft greens of spring and patches of wild flowers brightened the hills above Jerusalem. The holy days of the Passover, celebrating the escape of the Jews from slavery in Egypt, would not begin until the following Friday at sundown. But people were already busy preparing for it. The roads leading into the Holy City were crowded with Jews coming to attend the rites in the Temple. On the roads were also herds of cattle, flocks of sheep and carts loaded with cages of turtledoves. These were being brought to the Temple to be …

Read More »The Second Triumvirate 43 B. C. – 30 B. C.

AS THE news of Caesar’s death spread through Rome, sorrow, anger and fear took hold of the city. On March 17, two days after the murder, the Senate met again. Cassius, Brutus and the other assassins took their usual places. There was no doubt that most of their fellow senators felt that they had done the right thing in ridding Rome of a tyrant, but Caesar’ s veterans were still in the city, taking their orders now from Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, who had been his Master of the Horse, the commander of the cavalry. Mark Antony was still consul, he …

Read More »The City of Caesar 80 B. C. – 44 B. C.

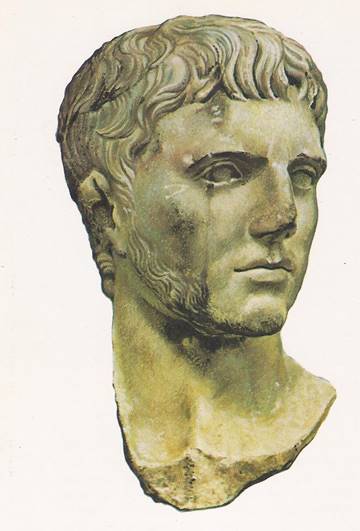

THE story of Rome in the years after Sulla’s death was the story of a partnership of power. It was the tale of three men who bargained for the world — a rich man, a poor man and a man who was not only a hero, but looked it. The rich man was Crassus, who had become a millionaire by setting up the only fire department in Rome. The tall buildings and narrow, crowded streets of the city made a fire a constant danger. When one house burned to the ground, the buildings on either side were likely to fall …

Read More »