AS MILLIONS of Americans hurried to work on the morning of October 24, 1929, it seemed like the start of an ordinary day. It seemed just as ordinary to the brokers and bankers who were entering their offices on New York’s Wall Street. True, the prices of stocks had been falling for several days, but that was nothing to worry about. There were bound to be ups and downs in the stock market and prices would surely rise again.

For never before had the United States known such prosperity as it did in the 1920’s. Herbert Hoover, who had become President seven months before, had said, “We in America are nearer to the final triumph over poverty than ever before in the history of any land. . . . We have not reached the goal, but given a chance to go forward with the policies of the last eight years, we shall soon with the help of God be in sight of the day when poverty will be banished from this nation.”

Many Americans agreed with him. They invested their savings in stocks and just as they hoped, the price of stocks rose. To make even more money, they bought stocks on margin — that is, on credit. They knew that they could be wiped out if stocks took a sudden tumble, but why should that happen? The richest men in the country said it wouldn’t and if they didn’t know, who did? The country was booming and anyone who didn’t get rich was a fool.

More and more Americans bought stocks and prices went higher and higher — until October of 1929. As the prices of stocks began to fall, people stopped buying and began to sell. The more they sold, the lower prices fell; the lower prices fell, the more they sold, but there seemed to be no reason to be seriously worried. This had happened before and would happen again. Always, in the past, stocks had bounced back up until they hit new highs. So why worry?

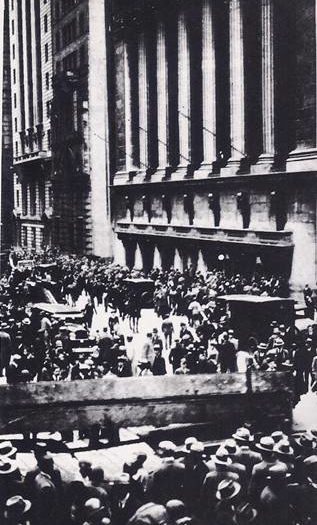

Then suddenly, on Thursday, the twenty-fourth of October, came a surprise — a dreadful and terrible surprise. No one wanted to buy and everyone wanted to sell. A roar rose from the Stock Exchange in New York as traders tried to keep up with the orders to sell. It was no use; the orders kept pouring in — sell, sell, sell. Prices kept falling — falling lower and lower and lower still! The news spread and crowds gathered in Wall Street and in the offices of brokers everywhere in the city. Men who had yesterday been rich or at least well-off stared at one another in disbelief, realizing that their fortunes had been wiped out.

Early that afternoon, the heads of the most important banks in New York met at No. 1 Wall Street, the office of J. P. Morgan and Company. Each put up $40,000‚000 — $240,000‚000 in all — to buy stocks and stop the fall of prices.

They did stop it, but only temporarily and by November prices had slid down to new lows. Yet, bad as the stock market crash was, worse was in store for the American people. A depression had begun, a great depression that would affect every person in the country. With the end of the 1920’s and the beginning of the 1930’s, businesses shut up shop, factories closed, prices of goods dropped, profits fell, wages were cut and millions of workers lost their jobs. By 1931, 7,000,000 people were out of work.

As jobless men tramped from one employment office to another, only to be turned away, they wondered what had happened. What had brought on the end of prosperity? What had changed America almost overnight? Had there been no warning?

Even years later, there would be no agreement on what had actually started the stock market panic, but there had been warning signals about the depression for some time. Farmers were already in trouble during the 1920’s. Prices of manufactured goods had risen faster than prices of farm products and farmers did not have enough money to buy the things they needed. The number of unemployed was around 1,000,000, and it had gone to 1,800,000 in 1928.

Wealth was unevenly distributed. In 1929, 24,000 families had yearly incomes of $100,000‚ while 42.4 per cent of all American families earned less than $1,500. Workers were producing more per man than they had before 1919, but wages had not gone up enough for them to buy the vast quantity of goods in the stores. High tariffs on imported goods — passed by Congress against the wishes of President Hoover — meant less trade with Europe. Unable to sell to America, European countries could not pay their debts or buy goods made in America.

While jobless men wondered what had happened in the past, they were worried about the present and fearful of the future. Their chances of getting a job seemed to grow less each day and each day ate up more of their small savings. What would they and their families do when it was gone? They looked for help to the government, especially to President Hoover. He was known as an able administrator. During and after World War I, he had been in charge of organizations supplying food to the starving people of Europe. Surely he would do as much for Americans.

President Hoover assured the people that the economy of the nation was basically sound and that it was now suffering from a lack of confidence. Confidence would return and so would prosperity. In fact, the return of prosperity was just around the corner and he had no intention of letting people starve.

He said, “This is not an issue as to whether people shall go hungry or cold in the United States. It is solely a question of the best method by which hunger and cold shall be prevented. It is a question as to whether the American people, on the one hand, will maintain the spirit of Charity and mutual self-help through voluntary giving and the responsibility of local government as distinguished, on the other hand, from appropriations out of the Federal Treasury for such purposes. . . . I am willing to pledge myself that if the time should ever come that the voluntary agencies of the country, together with local and State governments, are unable to find resources with which to prevent hunger and suffering in my country, I will ask the aid of every resource of the Federal Government because I would no more see starvation amongst our countrymen than would any Senator or Congressman. I have faith in the American people that such a day will not come.”

HOOVER AND THE DEPRESSION

Hoover wanted to avoid using Federal money for direct relief unless it was absolutely necessary; he believed this was best for the country and for the people. He did, however, take action in other directions. He called in the heads of large industries and tried to persuade them to cut wages as little as possible. To raise the price of farm products and help the farmer, he set up agencies that bought up surplus wheat and cotton. To help business, he set up the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, which loaned money to businesses such as railroads, banks and insurance and utility companies. To create jobs, he spent millions of dollars — more than any President before him — on the construction of roads and public buildings and for the improvement of rivers and harbours. Hoover also tried to help the European nations that were having difficulty paying their debts to the United States. He arranged a one-year moratorium on their payments — that is, for one year they would not have to pay anything.

The Reconstruction Finance Corporation saved many businesses from going bankrupt and would be continued in future administrations, but with conditions so bad, industry could not keep wages up. The farm program failed to raise the price of farm products. The construction program failed to create enough jobs. In spite of everything Hoover did, the depression grew worse and by 1932 the number of unemployed was about 12,000,000.

Men sold apples at five cents apiece on street corners, trying to earn a few pennies. Others walked the streets, begging from passersby, or stood in breadlines to get something to eat. Little villages of shacks, made of packing cases and scrap wood and metal, sprang up on the outskirts of cities. They were called “Hoovervilles,” a bitter joke at the expense of the President many Americans felt was not doing enough to help them.

Thousands of men, as well as boys in their teens, hopped freight trains and traveled the country, hoping that things would be better in the next town. Farmers who could not pay their debts were losing their farms. Home-owners who could not meet their payments were losing their houses. Families that could not pay their rent were put out on the streets. Sometimes children even searched through garbage cans, hoping to find something fit to eat.

In June of 1932, more than 15,000 veterans of World War I streamed into Washington to urge Congress to give veterans a bonus. Some of them brought their wives and children, and they camped near the city or on vacant lets near the Capitol. When Congress voted against the bonus, most of them left, but several thousand remained and Hoover ordered them ousted. Troops, led by General Douglas MacArthur, drove them out with tanks, tear gas and bayonets. The incident of the “Bonus Army” added to Hoover’s unpopularity, but the Republicans could find no one better to run for president in 1952. He easily won the nomination. The Democrats nominated Franklin Delano Roosevelt.