So at last, in the Pacific as in Europe, the guns were silent; the nations that had brought so much death and destruction to the world had been defeated, but victory alone was not enough. Governments had to be set up for the defeated nations, the destruction of war had to be repaired, hungry people had to be fed, industry and commerce had to be set in motion. Even more important, a way had to be found to keep war out of the world, to settle disputes between nations by peaceful means rather than by violence. The League of Nations, which had been set up for such a purpose after World War I, had failed, but the attempt had to be made again, for a third world war might well destroy all of civilization.

Even before World War II ended, President Roosevelt had been looking ahead to the future and the United States proposed the establishment of a new international organization. Her wartime allies were quick to agree. Meeting in Moscow in October of 1943, the foreign ministers of the United States, Britain, the Soviet Union, and China declared: “The four powers recognize the necessity of establishing at the earliest practicable date a general international organization, based on the principle of the sovereign equality of all peace-loving states, large and small, for the maintenance of international peace and security.”

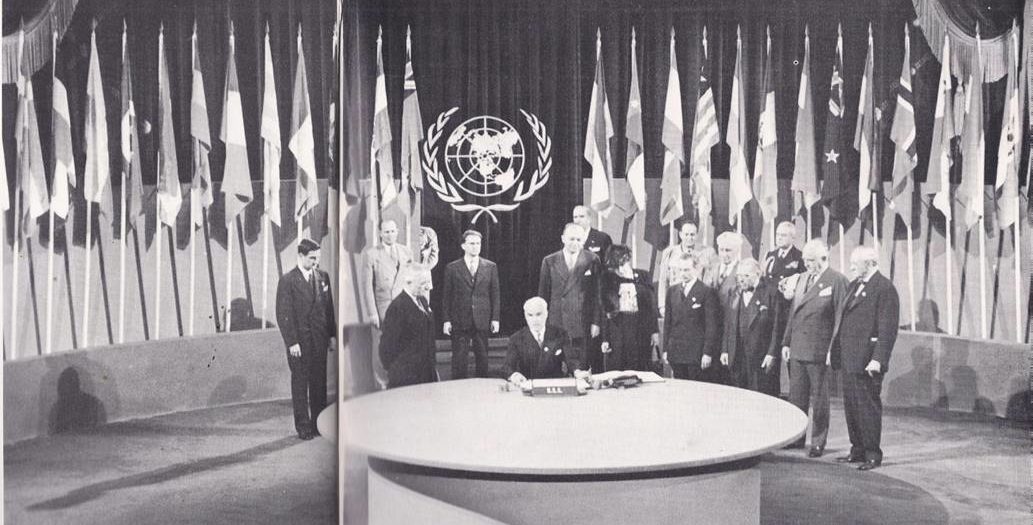

Representatives of the same four nations met at Dumbarton Oaks in Washington from August 21 to October 7, 1944, to discuss plans for the new organization. When Roosevelt, Churchill and Stalin met at Yalta in February of 1945, they agreed that the United Nations Conference on International Organization be held at San Francisco in April. The conference was held as scheduled and it was attended by representatives of fifty nations at war with the Axis powers. President Roosevelt was to have made an address at the opening session, but he had died less than two weeks before and President Truman welcomed the delegates.

“At no time in history,” President Truman said, “has there been a more important conference, nor a more necessary meeting, than this one. . . . You members of this conference are to be the architects of the better world. In your hands rests our future. . . . We must make certain, by your work here, that another war will be impossible. . .”

For weeks, day and night, the delegates worked to set up an organization to be known as the United Nations. On June 25 they completed the Charter. They signed it the next day and it was ratified by the governments of most of the nations on October 24, 1945.

The Charter began: “We, the people of the United Nations, determined to save succeeding generations from the scourge of war, which twice in our lifetime has brought untold sorrow to mankind and to reaffirm faith in fundamental human rights, in the dignity and worth of the human person, in the equal rights of men and women and of nations large and small; and to establish conditions under which justice and respect for the obligations arising from treaties and other sources of international law can be maintained; and to promote social progress and better standards of life in larger freedom and for these ends to practice tolerance and live together in peace with one another as good neighbours, to unite our strength to maintain international peace and security and to ensure, by the acceptance of principles and the institution of methods, that armed force shall not be used, save in the common interest and to employ international machinery for the promotion of the economic and social advancement of all peoples, have resolved to combine our efforts to accomplish these aims. Accordingly, our respective governments, through representatives assembled in the city of San Francisco, who have exhibited their full powers found to be in good and due form, have agreed to the present Charter of the United Nations and do hereby establish an international organization to be known as the United Nations.”

UN UNITS AND AGENCIES

The United Nations was divided into five basic units. The Security Council, which was to function continuously, was made up of eleven members. Five of them — the United States, Britain, the Soviet Union, France and China — were to be permanent members, while the other six were to be elected by the General Assembly and serve two-year terms. Each member was to have one vote, but each of the permanent members was to have the power to veto any measure before the Council.

In other words, any of the great powers could prevent the United Nations from taking action. In years to come, the Soviet Union would indeed use its veto many times. Such a use of the veto power aroused criticism, especially from Americans, who felt it wrong that any single nation had the right to block decisions made by the other members of the Council, but when the United Nations Charter was written, American officials were among the strongest supporters of the veto. They realized that, without the veto, the great powers might leave the United Nations if an important decision went against them and the entire organization might be ruined.

The Trusteeship Council was set up to administer “trust territories” — regions that did not yet have self-government but were under the protection of larger nations. To settle international disputes, the International Court of Justice was established. It would interpret treaties and points of international law, but only when called upon to do so by individual member nations.

The General Assembly was to consist of delegates from all the member nations, each of which would have one vote. The Assembly would meet regularly every year and could also be called into special session if an emergency arose. The Charter gave the Assembly the right to “discuss any questions or any matters within the scope of the Charter or relating to the powers and functions of any organs provided for in the Charter.” In time, the General Assembly was to be called “the town meeting of the world” and “the closest approach mankind has made to a world parliament.”

To carry on the day-to-day work of the United Nations, a Secretariat was to be set up. At its head would be the Secretary-General of the United Nations who would be appointed by the General Assembly on the recommendation of the Security Council. Although his powers were not defined, he was meant to be the United Nations’ chief executive officer.

Also to be elected by the General Assembly were the eighteen members of the Economic and Social Council, who were to serve for terms of three years. The duty of the Council was to seek “higher standards of living, full employment and conditions of economic and social progress,” as well as “international culture and educational cooperation” and “universal respect for and observance of, human rights and fundamental freedoms for all without distinction as to race, sex, language or religion.”

In addition, the Council was to coordinate the work of all the special agencies of the United Nations. Each of these agencies was to function in a specific field. The Food and Agricultural Organization ( FAQ) was to improve the living standards of farmers by distributing seed, tools, and scientific information. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, to which the rich nations were to contribute money, was to lend capital to poor nations at low rates of interest. The International Labor Organization (ILO), which was a continuation of an agency set up under the League of Nations, was to seek the improvement of working conditions for labour in all countries.

The United Nations Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) was to help children in poor countries with funds raised by voluntary contributions. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) was to bring different cultures and ideas together in the hope that the peoples of the world would come to understand each other better. The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) was to seek lower tariffs and encourage free trade among nations. The World Health Organization (WHO) was to seek higher standards of health and hygiene throughout the world and the control or elimination of diseases which afflicted millions of persons. There were many other agencies besides, but they were of lesser importance. Altogether, the purpose of the special agencies was to use the resources of the richer nations to raise the living standards of the poorer nations.

The first session of the General Assembly was held in London on January 10, 1946, with delegates from fifty-one nations attending. They elected the first five non-permanent members of the Security Council, named Trygve Lie, a former foreign minister of Norway, as the first Secretary-General and voted to make the United States the permanent headquarters of the United Nations.

Another instance of cooperation among the nations was the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration, commonly known as UNRRA, which was set up in 1943. Fifty-two countries contributed almost $4‚000,000‚000 for emergency aid to lands and persons suffering from the destruction of the war, with the United States contributing more than half. UNRRA assisted millions of refugees and displaced persons, distributed food, medicine and gave various other kinds of aid to such countries as China, Czechoslovakia, Poland, the Ukranian Soviet Republic, Yugoslavia, Greece and Italy. After UNRRA was discontinued in Europe in June of 1947 and altogether in March of 1949, its work was carried on by other United Nations agencies.

THE DEATH CAMPS

The allies were also united in taking action against the Axis war criminals, the men who had not only plotted war but had committed crimes against humanity. There could be no doubt that the Nazis had committed genocide — the attempt to wipe out a whole people — for the Nazis themselves had loudly proclaimed their aim to wipe out or enslave the peoples they considered inferior to the Germans. With the Jews, they had almost succeeded. They had destroyed nearly six million Jews — three-quarters of all the Jews in Europe, one-half of the total Jewish population of the world. Never in all history had there been such an attempt to wipe out an entire people.

Nor was there any lack of evidence of the Nazis’ intentions. As allied soldiers had moved into territory held by the Axis, they liberated whatever prisoners were left in the Nazi concentration camps. Among the camps whose names became known to all the world were Buchenwald, Dachau and Belsen in Germany, and Majdanek, Treblinka and Auschwitz in Poland. Even hardened soldiers, who had known the horrors of death on the battlefield, were shocked. They found piles of stinking, rotting corpses the Nazis had not had time to bury. They found gas chambers where men, women and children — most of them Jews and Poles — had been put to death with poison gas. They found furnaces where the naked bodies of the dead had been dumped and burned to ashes.

The Nazis had been systematic and well organized. They had carefully worked out all the details of the mass production of death. They had planned routes and means of transporting people to their places of execution. They had set quotas and schedules. They had even made the business yield some profit. They had stripped the victims of all their valuables, including the clothes on their backs and the gold fillings in their teeth.

From the prisoners, who themselves looked little better than skeletons, the Allied soldiers heard tales of death — of death by hanging, by torture, by starvation. They heard tales of weird medical experiments with no purpose, of human fat used to make soap, of human skin used to make lamp shades. They heard tales, too, from outside the concentration camps. In Czechoslovakia, for example, the Germans had wiped out an entire village. In revenge for the assassination of the Nazi in charge of the country, all the men of Lidice had been killed, the women and children sent out of the country and the buildings destroyed. There were countless other stories of hostages shot and tortured, of civilians shot down by machine guns after they had been forced to dig their own graves, of men and women torn to pieces by ferocious dogs. The stories sounded too horrible to be true, but official documents and reports of the Nazis showed that they were true and there were eyewitnesses besides.

To bring the criminals to justice, the United States, Britain, the Soviet Union and France set up an International Military Tribunal, with judges from each of the four countries. In November of 1945, the Tribunal began the trials of a number of leading Nazis. Because the trials were held in the city of Nuremberg in Germany, they became known as the Nuremberg trials. Among the Nazis who faced the judges was Hermann Goering, once the head of the mighty German air force; He was sentenced to hang but committed suicide by taking poison which he had concealed. Ten other Nazis were hanged, still others were sentenced to prison for life and a few were acquitted. An eleven-nation tribunal held similar trials in Japan, where former premier Tojo was among those condemned to death. Less important Nazis and Japanese militarists were tried before courts in various countries.

In the trials of the war criminals, in setting up the United Nations and UNRRA, the allies had acted together. The United States and the Soviet Union had become the two greatest powers in the world and it was plain to everyone that the peace of the world depended on their continuing cooperation. Yet, even before the war was over, differences had begun to develop between the two countries. At the Yalta conference in 1945, Stalin demanded that the Russians be given a slice of Poland and in return for entering the war against Japan, certain territories in the East. The question of Poland was not definitely settled at Yalta, but Stalin was promised North Sakhalin and the Kurile Islands in the East. The agreement on these eastern lands was kept secret until 1947.

Later, Roosevelt’s critics blamed him for giving in to Stalin and traced many post-war troubles back to Yalta. The answer of Roosevelt’s supporters was that he was interested, above anything else, in winning the war. At the time of the Yalta meeting, no one knew how long the war against Japan would go on and it seemed extremely important to get Stalin’s help.

Furthermore, at Yalta the Allies were still in agreement on a number of issues. They set up a control commission which would govern Germany immediately after the war. Germany would be divided into four zones of occupations; the United States, Britain, the Soviet Union and France would each be in control of one zone. The city of Berlin was also divided into zones, although it was well within the Soviet zone of Germany. The Allies agreed that Germany would be required to pay reparations and that its military power would be destroyed. It was at Yalta that plans were announced for punishing war criminals and for establishing the United Nations. The Council of Foreign Ministers was also set up; meetings could be called whenever necessary to discuss peace treaties or any other problem that might arise.

Although the leaders of the United States and Britain found Stalin difficult to deal with, as long as the war went on they found ways to smooth over their difficulties and remain staunch allies. After the war ended, however, the differences between the United States and the Soviet Union deepened. Stalin refused to allow free elections in Poland. Instead, Poland came under the control of Communists, as did Albania, Bulgaria, Rumania, Czechoslovakia and Hungary. In practical terms, it meant that these Countries were dominated by the Soviet Union and they became known as Russian “satellites.” Supported by the Soviet Union, Communists were also busy in Greece, Turkey, Italy and France. They were on the move in the East as well; in China they were fighting a civil war and threatening to take over rule of the country. Yugoslavia, too, was Communist, but it developed its own brand of Communism, went its own way and refused to be dominated by the Soviet Union.

It was true that the Soviet Union had suffered greatly from the war and had some reason for its desire to surround itself with friendly states. The Russians pointed out that they had lost 20,000,000 people, including civilians and that their industrial production had fallen by one-half. Millions of homes had been destroyed and the Soviet people had felt the full force of the horror of modern war. The siege of Leningrad, for example, had gone on for two and a half years and cost the lives of close to 1,000,000 persons.

At the same time, the Soviet Union was a dictatorship under Stalin. He wanted to extend his influence wherever he could and to do so he used dictatorial methods. Winston Churchill summed up the feelings of many Europeans and Americans in a speech at Fulton, Missouri, in March of 1946. Churchill said, “A shadow has fallen upon the scenes so lately lighted by the Allied victory. Nobody knows what Soviet Russia and its Communist international organization intends to do. . . From Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic, an iron curtain has descended across the Continent. Behind that line lie all the capitals of the ancient states of Central and Eastern Europe. Warsaw, Berlin, Prague, Vienna, Budapest, Belgrade, Bucharest, and Sofia, all these famous cities and the populations around them lie in what I must call the Soviet Sphere. . . Whatever conclusions may be drawn from these facts — and facts they are — this is certainly not the Liberated Europe we fought to build up. Nor is it one which contains the essentials of permanent peace.”

THE TRUMAN DOCTRINE

Convinced that Stalin was determined to expand the influence of the Soviet Union, the United States, backed by Britain and France, adopted a policy that became known as the “Truman Doctrine.” The aim of the Truman Doctrine was to “contain” the Soviet Union — that is, to confine Communism to that part of the world where it already existed and prevent its spread elsewhere. To accomplish this aim, the United States would form alliances with any nation opposed to Communism; it would also give aid to nations trying to put down Communism within their own borders. In 1947 President Truman asked Congress to appropriate money to aid Greece and Turkey; the reason, he said, was that “totalitarian regimes imposed on free peoples undermine . . . the security of the United States.” Congress agreed and voted $300,000‚000 for Greece and $100,000‚000 for Turkey.

Conditions in Greece were especially serious. Greek Communists had formed powerful guerrilla bands that operated freely in the northern mountainous regions of the country. Great Britain, which had liberated Greece from the Nazis, found it too difficult to fight the guerrillas, who were armed, trained and given sanctuary by neighboring Yugoslavia, which was Communist. The British asked the United States to take over the job and under the Truman Doctrine, the United States sent thousands of military advisers to Greece to organize a Greek army. Slowly, the Greek army gained the upper hand. The turning point came in 1948, when Yugoslavia broke with Russia and closed its borders to the guerrillas. The civil war ended two years later and Greece joined the nations allied with the West.

Several months after the Truman Doctrine was proclaimed, a still broader plan for aid to European nations was proposed by Secretary of State George C. Marshall, who had been chief of staff during the war. Speaking on June 5, he said that “Europe’s requirements for the next three or four years of foreign food and other essential products — principally from America — is so much greater than her present ability to pay that she must have additional help, or face economic, social and political deterioration of a very grave character. . . . It is logical that the United States should do whatever it is able to do to assist in the return of normal economic health in the world, without which there can be no political stability and no assured peace. Our policy is directed not against any country or doctrine but against hunger, poverty, desperation and chaos. Its purpose should be the revival of a working economy in the world so as to permit the emergence of political and social conditions in which free institutions can exist”

The plan, which was soon called the Marshall Plan, was welcomed by the non-Communist countries of Europe and in July representatives of Britain, France, the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxemburg, Austria, Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Eire, Greece, Turkey, Italy, Portugal, Switzerland and Iceland met to consider how to put it into operation. The Soviet Union and its satellites, however, rejected the plan, calling it “interference in the internal affairs of other states.” There was even some opposition to the plan in the United States because of its high cost. President Truman won support for the plan in Congress and the United States pledged to furnish $17,000,000‚000 in aid over a period of four years.

The Marshall Plan proved to be an enormous help to Europe in recovering from the war, but it sharpened still more the differences between the United States and the Soviet Union and the countries which were under the influence of the two great powers. In late 1947, Russia created the Communist Information Bureau, or Cominform, which was to direct the activities of Communists throughout the world. Several months later, Stalin ordered a purge to be carried out in Russia and the other Communist countries against all people who showed, or seemed to show, any sympathy for the West. The iron curtain descended on all of Eastern Europe, including Czechoslovakia, the one country in Eastern Europe that had remained democratic. In February, 1948, a Communist revolution, engineered by Moscow, overthrew the freer elected Czech government and established a dictatorship. By 1948 the world was divided into two camps and between the two camps there was war — not a shooting war in which army fought army, but a “cold war” of politics and political maneuvers.

The problem of Germany was particularly troublesome. The allies could not agree on the terms of a peace treaty and Germany remained divided into four zones of occupation. So did the city of Berlin, which was a hundred miles within the Soviet zone. In June of 1948, the United States, Britain and France decided to take steps to unite their zones politically and economically, in both Berlin and Germany as a whole. The Soviet Union then withdrew from the Allied Control Council.

To aid Germany’s economy, the three Western powers issued a separate currency for use in their zones. The Russians at once banned the use of the new currency in their zone, including that part of Berlin which was under their control. On June 24, the Russians announced that because of “technical difficulties” it was placing a blockade on all goods brought into the Western sectors of Berlin. All traffic by road, rail and water was cut off. The Russians also stopped power stations from supplying electricity to the Western sectors of the city, giving as their reason a shortage of coal. The actual reason for the blockade was clear. The Russians were trying to force the Western powers out of the city; with 2,250‚000 residents of Berlin going hungry, the question of the control of the city might be settled on terms advantageous to the Soviet Union.

The Western powers, however, refused to allow the Berliners to go hungry. The Americans and the British put into operation the Berlin Airlift, bringing food, clothing and other goods in by air. Planes were loaded with cargo at Frankfort and Wiesbaden and before long they were landing in Berlin every three minutes, throughout the day and night. Altogether, some 2,000,000 tons of supplies were flown into Berlin during the period of the blockade.

Even so, the quantity of goods was not enough to meet the needs of so many people and the Western allies took further steps against the Russians. They began a counter-blockade, cutting off supplies of raw materials and coal from all of the Soviet zone. At first the Russian leaders said that they would stop their blockade if the Allies would drop their plans to set up a West German government, but conditions in the Soviet zone grew worse and in May of 1949 the Russians came to an agreement with the Allies to end the blockade. After 320 days, the Russians had lost the “Battle of Berlin.”

The Western allies then took measures to put Germany on the way to self-government. On May 12, 1949, the Federal Republic of Germany was established and after elections were held, Konrad Adenauer became chancellor. Meanwhile, the Russians were setting up the German Democratic Republic in their own zone. The result was that Germany was a divided country with two separate governments, one allied with the Western powers, the other with the Soviet Union. This again widened the gulf between the two sides in the cold war, especially when, in the 1950’s, West Germany showed signs of a surprisingly swift return to prosperity.

As a matter of fact, all the European countries that received Marshall Plan aid were recovering from the war at a pace faster than anyone had expected. At the same time, changes were taking place in most of these countries — changes that would set the tone of politics in the post-war years. Parties of both the left and the right moved closer to the center; there was less extremism than there had been before the war and greater reliance on parliamentary methods.

In England, elections had been held on July 5, 1945 — just one month after the war ended in Europe. The Labour party won the election and the Conservatives, the party of Winston Churchill, was turned out of office. The people still looked on Churchill as a great man who had done a magnificent job in the dark years of the war and had led them to victory. Now that the fighting was over, however, they wanted a better and more secure life. This could only be brought about through reforms and Churchill’s party was not the party of reform.

The Labour party socialized certain industries and made England into what became known as a “welfare state” — a state in which the government was responsible for the welfare of its citizens. During the years to come, the Labour party would not always win the elections, but even when the Conservatives gained control of the government, they would not seriously challenge the idea of the welfare state and certain measures, such as social insurance and socialized medicine, would become an accepted part of British life.

In foreign affairs, Britain remained an ally of the United States and the Western nations. Britain was forced to give up control of many of its colonial possessions and never again would it be the great imperial power it had been in the past. Nevertheless, it was still a stronghold of democracy and it would continue to play an important part in European affairs.

France, too, would be forced to give up some of its colonies, particularly in Indochina and North Africa. After the war, there was again conflict among the various political groups and not until 1946 were the French able to agree on a new constitution and establish the Fourth Republic. The Communist party was especially strong and some extreme right-wing groups were also active. The Communists made no attempt to bring about violent change, the right-Wing groups could get little support and at last, under the leadership of de Gaulle, France began to solve some of its problems and to grow more prosperous.

In Italy, an election in 1946 ousted the monarchy and set up a republic. As in France, the Communist party was strong, but it made no attempt at violent revolution. Its strength was balanced by that of the Socialist and Christian Democrat parties and in time it would become more a party of protest and reform than a party of revolution. Furthermore, increasing prosperity made it impossible to get popular support for a program of violent change and in the cold war Italy supported the United States and was part of the Western alliance.

In Greece, civil war broke out as Communist guerrillas fought to take over the nation, but in 1949, with United States aid, they were finally put down. Spain, which had been sympathetic to the Axis but had not entered the war, remained a fascist dictatorship under Franco; Portugal, too, had a totalitarian government, but its rule was somewhat milder than that of Franco’s.

The cold war took a more dangerous turn in 1949, when the Soviet Union succeeded in producing an atomic bomb. The two most powerful nations in the world now had the ability to destroy each other; in fact, as both countries built up stockpiles of even more destructive bombs, the entire world lived under the threat of extinction.

Meanwhile, there were changes taking place in the Orient as well as in Europe — and it would be in the Far East that open conflict would break out between the Western and the Communist powers.