In 1871 there occurred one of the strangest meetings in history. The place was Ujiji on Lake Tanganyika in the heart of Africa. The men who met were David Livingstone, a Scottish missionary who was also a doctor, and Henry M. Stanley, a newspaperman. Livingstone had come to Africa about thirty years before. Anxious to spread Christianity and civilization among the Africans, in this unknown and mysterious continent, he had undertaken long trips into the interior. For several years, however, Livingstone had not been heard from, so the New York Herald sent Stanley, a roving reporter, to look for him.

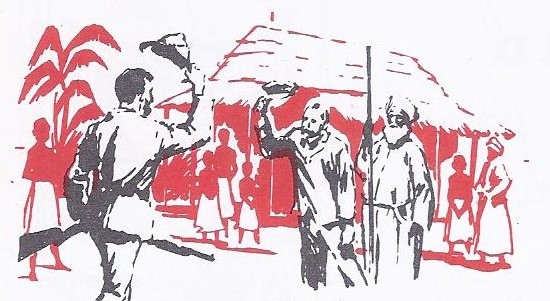

After what seemed like an endless journey through the dark forests of the African jungle, Stanley finally came upon Livingstone and his small party in a native village. There in the market place stood Livingstone, weak from fever and worn out from years of exploring regions hitherto unknown to white men. As the story goes, Stanley advanced toward him, rushed with the excitement of finally meeting the man he had for months been trying to locate. It would have been natural at such a dramatic moment for Stanley to shout a welcome or to rush forward and clap Livingstone on the back. But Stanley merely tipped his hat and said, “Doctor Livingstone, I presume?” as if this were an everyday meeting of two men on a city street!

Stanley’s meeting with Livingstone occurred at a time when Europeans were taking a new interest in African continent. Within a few years several European countries had become engaged in a scramble for colonies. In fact, by the early years of the twentieth century, all Africa except for two or three areas had been taken over by one European power or another. Nor was interest in colonies confined to Africa. During the same years the industrialized Western powers had seized colonies or obtained control of various areas in Asia and numerous islands of the Pacific. The great powers in both hemispheres even claimed large sections of Antarctica, the uninhabited continent surrounding the South Pole!

The procedure whereby more powerful nations obtain control over less powerful peoples is called imperialism. (Imperialism comes from the Latin imperium meaning “empire”-the rule of one country over colonies or other states.) Imperialism at the end of the nineteenth century did not always take the same form. Sometimes European states gained outright ownership of colonies. Sometimes they obtained a controlling voice in the government of “independent” native states or “on special trading privileges. No matter how it came about, imperialism, or the growth of empires, resulted in the spread of Western ways of living among some of the less advanced peoples. And imperialism had important effects on the Western powers themselves.

Why imperialism flared up in the late nineteenth century and how in particular it affected Africans. We find answers to the following questions:

1. Why did interest in imperialism revive in the late nineteenth century?

2. How did European powers carve out empires in Africa?

3. How did imperialism affect the African?

1. Why did interest in imperialism revive in the late nineteenth century?

Empire building is as old as history. Empire building was nothing new. You will recall that Egypt, Persia and Rome all possessed empires in ancient times. You also know that from Columbus’ day to the late 1700’s five European nations — Portugal, Spain, France, Holland, and England — competed for distant colonies. In order to increase its wealth, each of these countries tried to control the trade of its own colonies and to bar foreigners from sharing it.

Empire building died down during the early 1800’s. For many years following the end of the Seven Years’ War in 1763, there was less interest in acquiring new colonies. The French had lost nearly all their colonies in India and in North America. The Spanish, Portuguese and Dutch already had more colonies than they could manage. Germany and Italy, still divided into many states, had no colonies. In fact, from the time the French Revolution broke out in 1789 until the late 1800’s, Europeans were kept busy at home with efforts to win personal liberty and national unity.

Even the British were half-hearted about gaining more colonies. To them, the American Revolution indicated that colonies could not be counted on to remain a source of profit to a mother country. Once colonies became strong enough, they would seek independence. This same lesson was borne out a little later when Spanish America broke away from Spain and became a group of independent republics. Moreover, the idea of free trade was gaining headway in Great Britain in the early nineteenth century. If all colonies could trade freely with any nation, it made little difference (so far as commerce was concerned) whose colonies they were. To use a homely comparison, what would be the advantage of owning a cow and paying for her hay if any passer-by could milk her?

A new colonial movement began. Then, after years of lessened interest in colonies, a new scramble for overseas possessions started in the middle of the 1800’s and was in full swing by the 1880’s. This new interest in empire building resulted from (1) a growth in national pride, (2) the spread of the Industrial Revolution and (3) the improvements brought about by science. Let us see how each of these factors aided the growth of imperialism.

National pride encouraged empire building. National pride whipped up enthusiasm for colonies. The German states, had united into a powerful nation by 1871. Germans felt that colonies meant more power and more prestige. Italy, too, had become a united nation about the same time and felt the same way, that gaining colonies would improve its position among the nations of the world. France, stung by defeat in the Franco-Prussian War, wanted to regain its standing among nations. By building up a new empire in lands across the sea, France could make up for the loss of Alsace and Lorraine These three countries therefore eyed distant parts of the world with new interest.

National pride also drew Great Britain into a new race for colonies. So long as a Pacific island or a strip of African jungle was claimed by no one but some native Chieftain who was willing to trade, the British had been content to let it alone, but when other European powers started seizing colonies, Great Britain, ruler of the seas and the greatest colonial power, could not stand on the side lines.

Industrialized countries sought new markets. More important even than national pride in encouraging empire building was the spread of the Industrial Revolution. The use of machines, as we know, made it possible to produce more and more goods. In the early nineteenth century England had such a head start in manufacturing that its merchants and businessmen found no difficulty in selling their products in other countries. By the 1870’s, however, the United States, France, Germany and Belgium, as well as other European countries, were turning out goods in rapidly growing quantities. Businessmen and statesmen in all countries, including Great Britain, began to ask, “Where can we find more people to buy our goods?” People who lived in parts of the world that were less advanced or harder to reach supplied the answer. Cotton cloth, knives, tools and weapons were in great demand among such peoples.

Industrialized countries needed raw materials. Industrialized countries required not only greater markets but also ever-increasing quantities of raw materials to keep their factories busy. The textile industry in Great Britain, for example, depended on huge quantities of imported raw cotton and wool. As the Machine Age progressed, the list of desired raw materials widened to include rubber, copper, tin, aluminum, oil and other products. No industrialized country possessed sufficient quantities of all these raw materials. Nor did it like to depend on rival nations to supply its needs. Colonies or areas where an industrialized nation could control trade seemed the answer to this problem of raw materials.

Demands for tropical goods increased. Colonies in warmer climates were valuable because they could supply certain products not grown in temperate climates. There was a growing demand for such products in Europe and the United States. To illustrate this point, consider some products in use in your own home today. Tea may come from India or from Ceylon. Coffee comes from Java in the East Indies (hence the popular expression “cup of Java”) and in much greater quantities from Brazil and the Caribbean area.

The cacao bean from which chocolate is derived grows in Latin America and in Africa. From the Pacific islands comes copra, or coconut meat, used in butter substitutes and in the manufacture of soap. Your sugar may be made from the sugar cane grown in the West Indies. The bananas in the fruit bowl are from the Caribbean region. Pineapples come from Hawaii.

On a warm day you may sit in a hammock. The hemp fibre of the hammock may have been grown in the Philippines. Although production of synthetic or artificial rubber has increased greatly in recent years, natural rubber from the East Indies is still imported in large quantities into the United States. If you check the amount of rubber used in common household articles, you will be truly amazed.

Other fairly common things are made wholly or partly from imported materials. The piano in your home may have keys made of elephant ivory from Africa. If you have mahogany furniture, the wood was probably shipped from southern Mexico at Central America. Mahogany also is found in the heart of Africa. You may have made airplane models of balsa wood, which comes from tropical countries. From these scattered illustrations it is easy to see how important trade with tropical and semi-tropical lands can be. You can also understand why traders and businessmen saw the advantage of having colonies from which such products could be obtained.

TIMETABLE EXPLORATION OF AFRICA

The Coast

Prince Henry the Navigator sent Portuguese ships along the West African coast as far as Guinea, 1418-1460

Portuguese navigator Dias rounded Cape of Good Hope, 1488

Vasco da Gama Visited eastern coast on his way to India, 1497-1499

Dutch founded a settlement at Capetown, 1652

The Interior

British African Association founded to explore the continent, 1788

Mungo Park, a Scot, discovered the upper Niger River in West African region, 1795 – 1805

René Caillé, a Frenchman, crossed the Sahara from Guinea to Morocco, 1827 – 1828

Richard Lander, an Englishman, followed the Niger to its mouth, 1830-1834

David Livingstone crossed southern African regions (present day Rhodesia and Angola) from coast to coast, 1853-1856

Lake Victoria, source of the Nile River, was discovered by John Speke, 1859

Samuel Baker travelled from Egypt up the Nile to its source, 1862 – 1864

Henry Stanley traced the Congo River from its sources to the Atlantic, 1874 – 1877

Colonies provided opportunities for investment. Finally, businessmen in industrialized countries saw another advantage in empire building. The Industrial Revolution had made it possible for them to reap large profits. As a result, business men were anxious to put this wealth or capital to work so as to make more money. By the late 1800’s they found that they could make bigger profits by financing mines, plantations, railroads and other ventures in underdeveloped countries than they could by lending their money at home. Investors naturally wanted to invest their wealth where they were reasonably sure it would be safe. The best safeguard was to have their governments take over and rule the areas where their money was invested. So businessmen, merchants and bankers became strong supporters of imperialism.

Modern science aided imperialism. National pride and the growth of modern industry caused nations to seek colonies; science helped them to obtain and hold colonies. In the 1500’s, 1600’s and 1700’s the colonies established by European nations in the tropics were located chiefly along the coast or in high altitudes. Tropical jungles usually proved deadly for Europeans. Many a hardy explorer who pushed into the steamy jungles never came back. Those who did were often the weakened, shivering ghosts of the strong men who had started out. Diseases such as yellow fever and malaria in particular were enemies of Europeans.

One reason why the French failed to build a canal across the Isthmus of Panama in the late nineteenth century was widespread tropical disease in that region. After scientists discovered that mosquitoes carried malaria and yellow fever, sanitation squads began to drain or to cover with a film of oil the stagnant pools where the disease carrying mosquitoes laid their eggs. This same knowledge made it possible for the United States to build the Panama Canal a few years later. In time drugs and cures for other tropical diseases were developed. Progress in medical science, then, helped people from temperate climates to live in areas formerly considered too unhealthy.

Science also contributed to empire building by making possible improved means of transportation and communication. The railroad, telegraph, cable and ocean-going steamships brought distant places much closer together. Smaller steamboats chugged up rivers into interior regions hitherto hard to reach.

The new colonies did not attract permanent settlers. Often the first people to venture to strange lands and fever-ridden jungles were scientists and missionaries. They were followed by government officials, traders, planters and engineers. These people seldom expected to be permanent settlers. They planned to return home in a few years after their duties had been accomplished or they had become wealthy. In this respect the Europeans who opened up colonies after 1870 were unlike the people who had left England, France, Holland and Germany in the 1600’s and 1700’s in search of new homes in the New World.

Imperialism was world-wide. The search for colonies during the 1800’s affected all sorts of places — surf-circled, lonely Pacific islands ruled by native chieftains, China’s Crowded coastal cities and vast African territory and millions of people. Western powers also influenced new republics in Latin America as well as people of southeastern Europe who were unhappy under the rule of the Sultan of Turkey. We see how empire building took place in Africa, but remember that while the industrialized nations of Europe were greedily dividing Africa among themselves, they were not overlooking chances for power and profits elsewhere.

2. How Did European Powers Curve Out Empires in Africa and control Africans?

Most of Africa was a closed book to Europeans before the late 1800’s. They did, of course, have some knowledge of the Moslem states lying between the Sahara and the Mediterranean Sea, but Europeans knew little about the rest of the continent. Few of them had ever heard about the highly developed Negro kingdoms of West African region. One of the earliest of these was Ghana, which had probably been founded before the Christian era. Before its decline in the 1200’s, Ghana traded its agricultural products in such distant places as Baghdad and Cairo. Other kingdoms became powerful in West Africa after Ghana’s decline but for various reasons — civil war, invasion, drought — also eventually lost power.

By the late 1800’s, Europeans (beginning with the Portuguese) had explored the coasts of African tropics, trading for ivory, gold and slaves. The Dutch had planted a small settlement at the southern African tip which Great Britain seized during the Napoleonic Wars, but the great African interior was largely unexplored by Europeans.

Explorers and missionaries first entered the African wilderness. Where traders hesitated to enter the fever-ridden African jungles in search of wealth, explorers and missionaries plunged ahead. Most prominent of this group was David Livingstone.

Livingstone had been trained as a doctor in his native Scotland and went as a medical missionary to Africa in 1840. Instead of remaining in white men’s settlements along the coast, he decided to open mission stations far in the interior. In his travels Livingstone uncovered valuable information about the land and its peoples which he reported to scientists and the government back in Great Britain. He exposed the slave trade which the Arabs carried on among the Negroes and roused world wide feeling against it. Before his death in 1873 he had crossed Africa from the Atlantic to the Indian Ocean and from the Cape of Good Hope to the equatorial jungles along the Congo River. When he died, devoted natives bore his body across half a continent to the coast so that it might be sent by ship to his native land.

After finding Livingstone, Stanley carried on explorations of his own in the African interiors. Stanley foresaw what a rich trade could be built up between Europe and this undeveloped continent. He tried to get Great Britain to take over and run the Congo region, but the British showed little interest and the chance was seized instead by the ruler of Belgium.

The Congo Free State was set up under Leopold II of Belgium. King Leopold II of Belgium announced that he was interested in exploring the Congo region and in bringing civilization and Christianity to the natives. Leopold also stated that he wanted to put an end to the cruel slave trade. So the statesmen of Europe set up a Congo Free State in the heart of Africa with King Leopold in charge. According to the arrangement, the Congo was to be considered King Leopold’s own property. European statesmen believed that this was a good way to settle a troublesome problem. If Great Britain, France or Germany were handed so rich a territory, other nations might become jealous, but they were not likely to fear the power of the king of little Belgium.

Leopold’s rule in the Congo aroused international protests. Conditions in the Congo soon became so bad as to shock the entire world. Forgotten were Leopold’s promises to improve conditions in the Congo. Instead he became interested chiefly in obtaining rubber and gaining profits from the rubber trade. As manufacturers in industrialized countries found more uses for rubber, Leopold increased his demands on the natives.

The natives for their part saw no reason why they should spend all their days tapping wild rubber trees and gathering the rubber sap for Leopold’s benefit. To get the work done Leopold imposed taxes, payable in rubber, on native villages. Those villages which failed to turn in their quotas were punished. Native troops, stlll half-savage, were turned loose to burn the villages and kill the inhabitants. Their cruelty caused such a scandal that Leopold was finally forced to sell his holdings in the Congo to the Belgian nation in 1907. Under this new arrangement the government of the Congo improved.

Rivalry for colonies in Africa became keen. Meanwhile King Leopold’s profitable adventure had stirred other European governments to stake out colonial claims in Africa. In the scramble, little attention was paid to the wishes of the natives and not much to the claims of other powers. Although the leading governments of Europe set up rules for obtaining colonies and settling disputes, traders and government agents made secret deals with native Chieftains and used various tricks to outwit their rivals.

Land-hungry Europeans carved up Africa. The race for colonies in Africa took place so rapidly that early in the twentieth century only two African states — Liberia and Ethiopia — remained independent. You will want to consult the map to locate these two countries and to see what parts of Africa had come under the control of each of the European colonial powers by 1914.

Belgium of course had the Belgian Congo. Spain held a few small colonies on the north and the west coasts of Africa. The Portuguese expanded their coastal settlements into sizable colonies in the western and eastern portions of South Africa. The Italians gained Libya on the Mediterranean and other lands on the eastern coast.

Germany took four colonies in Africa. For a few years after it had become united, Germany did not join the race for colonies in Africa. Bismarck used to say he was “no colony man”; problems outside Europe interested him very little. German traders, however, convinced him that they were entitled to the protection of their government. Besides, the powerful and ambitious new German Empire could hardly stand aside and let other nations gobble up all of Africa. So in the 1880’s Bismarck planted the German flag in four unclaimed sections of Africa. (Look again at the map to locate these areas.) These German colonies, however, were not as valuable as the parts of Africa held by Great Britain and France.

France and Great Britain obtained the lion’s share. Of all the European powers, France and Great Britain by the early twentieth century controlled the largest empires in Africa. As the map indicates, France had carved out an empire many times the size of France itself in the northwest part of Africa. In addition France held the huge island of Madagascar in the Indian Ocean east of Africa. Great Britain controlled South Africa and a broad band of land reaching northward from the headwaters of the Nile to the Sudan and Egypt.

The story of how France and Great Britain obtained these great empires began before the main movement to carve up Africa in the late 1800’s. We do not have space to tell the complete story. But parts of it will be told in order to illustrate important facts about the growth of imperialism.

In northern Africa, long-established civilizations existed. In much of central and southern Africa, colonies could be obtained fairly easily. The country was thinly settled and the native tribes were not highly civilized. Often they could be persuaded to give up land, or if they resisted, they could be overcome by the superior weapons of Europeans. In contrast, the peoples in the Moslem states north of the Sahara represented a well established civilization. With the exception of Morocco, which was ruled by an independent sultan, these North African states belonged to the Ottoman Empire and paid tribute to the sultan of Turkey at Constantinople. France and Great Britain had to use less direct methods to win control in North Africa.

The French gained Algeria and Tunisia through “incidents.” A favourite way to get control of countries with established civilizations and governments was to use some event or incident as an excuse to take over control. This the French did in both Algeria and Tunisia. When an Algerian ruler struck the French consul with a fly swatter, the French took it as a national insult and insisted on punishing the Algerians. In 1830 a French army was sent to conquer Algeria. After some years of fighting the conquest was completed. Algeria was annexed to France and policed by the famous French “Foreign Legion.” In 1881 the French took over Tunisia. Their excuse was that the Tunisian government had not paid interest on its loans and that Tunisian tribesmen had attacked Algeria.

The British took Egypt under their protection. Financial disorders in turn gave Great Britain a foothold in Egypt. Egypt had been ruled by the sultan of Turkey for centuries. In the nineteenth century it was ruled more or less independently by a governor called the khedive. One of these khedives named Ismail decided to make Egypt a modern industrial country. Ismail’s ambitions were expensive and to raise money he sold Egyptian bonds in France and Great Britain. Ismail got so deeply in debt that in 1875 he offered for sale his own shares in the newly built Suez Canal. The British Prime Minister Disraeli jumped at the chance to gain a controlling interest in this canal because it provided the shortest route between Great Britain and India. Great Britain and France also took charge of Egypt’s muddled finances.

Egyptians disliked having their finances controlled by outsiders. Some of them rose in revolt with the cry of “Egypt for the Egyptians!” In the fighting that followed a number of Europeans were killed, so in 1882 the British sent an army to Egypt. Though the riots were put down quickly, the British did not want to leave until peace and order were fully restored. What had begun as a “temporary occupation” turned into British rule in Egypt. Yet Egypt was still supposed to be a Turkish province! In 1914, when Turkey fought against Great Britain in World War 1, Egypt became a British protectorate. Under a protectorate a strong nation “protects” a weak one and supervises its government.

British rule helped Egypt in many ways. British engineers built dams to control the waters of the Nile, on which Egyptian farmers depended for water for their crops. Under British control Egyptian law courts were improved, the army modernized and finances straightened out. The British also improved health and sanitation. Nevertheless the Egyptians were not happy. To them British rule was foreign rule. What country wants another nation, no matter how efficient, to step in and take over? Most nations would rather govern themselves badly than be governed well by foreigners.

Imperialism caused dangerous crises between rival powers. Africa is so large a continent that you would think the different European powers could have satisfied their desire for colonies without quarreling amongst themselves. Each nation, however, was determined that it would not be outstripped in empire building by others As a result, bitter national rivalries arose which at times almost led to war. Two areas where national rivalry threatened to upset the peace were the Sudan and Morocco.

The British met resistance in the Sudan. South of Egypt on the upper Nile lies the region called the Sudan. This region supposedly belonged to Egypt, but that fact meant nothing to the wild tribesmen of the Sudan. Their leader was a fanatical Moslem called the Mahdi, meaning “the divinely guided one.” The Mahdi stirred up so much trouble in the mid-1880’s that the British government decided to withdraw from the Sudan. General Charles Gordon was sent up the Nile with orders to bring back British and Egyptian troops from that wild and distant country.

Gordon was nicknamed “Chinese” Gordon because of his earlier adventures in China. He was a dashing and gallant soldier whose experience as governor-general of the Sudan had given him sympathy with African native peoples. Though he seemed an ideal choice for the job, Gordon was not the man to carry out orders which he thought wrong. When he reached the Sudan, he concluded it would be wicked to abandon this fertile region to bloodshed and chaos. He decided not to follow his orders but to remain in the Sudan. This decision cost Gordon his life. The British finally sent an expedition to reinforce him, but it reached Khartoum, the chief City of the Sudan, three days too late. The Mahdi’s soldiers had already killed Gordon and his men.

During the 1890’s Great Britain took a new interest in the Sudan. In this region lay one of the two sources of the Nile, Egypt’s vital water supply. Besides, both Belgium and France were enviously eyeing the region. In 1898 a mixed force of British and Egyptian troops led by General Kitchener pushed into the Sudan. Kitchener smashed the native forces and thus avenged Gordon’s death.

France challenged British control of the Sudan. Now trouble developed from another direction. The French had never agreed that the British had the right to occupy Egypt. Furthermore the Sudan, they said, had long been outside of Egypt’s control. It was a sort of “no man’s land” in which France had as much right as any other nation. The French therefore sent a Major Marchand into the Sudan. The Major, they said, was leading a “scientific expedition.” At the town of Fashoda on the Nile River, Kitchener’s and Marchand’s forces came face to face.

The Sudan question almost led to war with France. For a time Europe was on the brink of war. Kitchener claimed the whole of the Sudan in the name of Egypt, while Marchand claimed at least a part of it for France. Both men refused to budge. Newspapers in Great Britain and France fanned the flames of public feeling. Britain was not going to tell France what to do; France was not going to decide what Britain’s policies should be. So ran the arguments.

Fortunately the crisis blew over, for the French knew they did not have a strong enough navy to fight the British. More over, France could not afford to quarrel with Great Britain while still on unfriendly terms with Germany. An agreement was reached which gave Great Britain the richest part of the Sudan along the Nile River. This region was taken over in the name of Great Britain and Egypt jointly and appeared on the map as the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, but for all practical purposes the Sudan became another British colony.

French interest in Morocco aroused international tension. The story of how the French got control of Morocco is another illustration of the dangerous rivalry that imperialism caused between nations. The people of Morocco are proud, warlike and faithful Moslems. In the late nineteenth century they became suspicious that the French wanted to add Morocco to their other North African colonies. The French, however, moved slowly and cautiously, so as not to upset either the people of Morocco or the other European powers. They flattered the Sultan of Morocco, gave him gifts and tried to win his favour. They quieted Spain by promising a small portion of northern Morocco if and when Morocco was annexed by France. They agreed to back Italian ambitions to rule Tripoli, now called Libya and in 1904 the French even agreed to let the British do whatever they liked in Egypt, provided the British would not interfere with French plans in Morocco.

To Germany, however, the French offered nothing. They felt that what happened in Morocco was no business of Germany’s. The angry German Kaiser, William II, struck back in 1905 by insisting upon complete independence for Morocco. He also demanded an international conference to discuss the Moroccan question. Other nations agreed and the following year a conference was held at Algeciras, Spain. The statesmen present agreed that Morocco should remain independent and that all nations should be given equal trading rights there. France got something too. Along with Spain, France was given the right to “police” Morocco, the next best thing to outright control.

A second Moroccan crisis arose. The fate of Morocco, however, was not yet settled. In 1911 another crisis arose. Rioting swept Morocco and the French sent an army to restore peace. The Germans remembered how the British forces which had gone into Egypt to bring order had remained indefinitely. If the French kept an army in Morocco, might not that country become French territory?

When the German government sent a warship to Morocco to protect German interests, the situation became tense. Any thing could happen, because national pride was at stake. Once again bargaining took place among the European powers. The threat of war disappeared when Germany gave way to France in Morocco and received in return a piece of land in tropical Africa. In 1912 France made Morocco a protectorate. Morocco became French territory except for a small northern strip which was acquired by Spain.

The story of empire building in the Sudan and Morocco shows how European nations (1) sometimes came close to war because of conflicting claims and (2) made “deals” with each other with little regard for the wishes of the Africans themselves.

England had long been interested in South Africa. There remains the dramatic story of how Britain won control of South Africa. As you already know, the British during the Napoleonic Wars had seized the Dutch colony at the southern tip of Africa. By about 1840 British settlers had occupied territory as far to the northeast as Natal. (See the map on page 562.) The coming of the British led to trouble with the Dutch settlers, because they disliked British rule, many of the Dutch farmers piled their household goods into huge wagons and “trekked,” as they called it northward into the wilderness. Their migration was much like that of American pioneers who moved westward to Oregon and California. The Dutch speaking pioneers, called Boers (bohrz, the Dutch word for “farmers”), had much of their wealth in livestock. In their new homes the Boers established their own simple way of life and set up two republics, the Transvaal and the Orange Free State.

Ill feeling between the British and the Boers increased. Were these new Boer republics subject to the British government? No one was quite sure, but in any case the Boers managed their own affairs very much as they pleased. Matters might have gone on this way indefinitely had not gold been discovered in the Transvaal in 1886. When gold seekers, including many Englishmen, poured into the Transvaal in large numbers, the Boers became alarmed. Suppose the British finally outnumbered them. Would the Boer way of life be destroyed? Would the British annex the Transvaal and bring an end to Boer independence? To prevent such happenings the Boers denied “outlanders,” the foreign immigrants, the right to vote.

British empire building in South Africa was advanced by Cecil Rhodes. Meanwhile a remarkable Englishman named Cecil Rhodes had come to South Africa because of ill health. Through diamond mining, he built up a fortune, a large part of which he willed to Oxford University. It was to be used for scholarships to bring outstanding men students from the United States and British possessions to Oxford. These students are called “Rhodes scholars.” Thirty two scholarships are assigned each year to students from the United States.

Rhodes combined with his business ability, a firm faith in empire building. He believed, as he expressed it, that the Almighty meant as much of the earth as possible to become Anglo-Saxon. Just as Clive’s name is linked with the growth of British power in India, Rhodes’ name is connected with the spread of British control over Africa. Rhodes added to Britain’s empire the huge region which still bears his name, Rhodesia. He even dreamed of an unbroken chain of British-controlled territories stretching from Cape Colony, South Africa, to Cairo, Egypt. The Boer republics were an obstacle in the way of his goal. Rhodes insisted that the Boer republics should grant the same rights to British settlers as to the Dutch. If they would not do this, said Rhodes, they should be forced to join the British Empire.

The British and Boers came to blows. President Paul Kruger of the Transvaal stubbornly refused these demands. Kruger was determined at all costs to uphold the independence of the Boer republics. Then in 1895 a friend of Cecil Rhodes, Dr. Leander Jameson, invaded the Transvaal, leading a band of armed Englishmen. Although Jameson and his raiders were speedily captured by the Boers, the incident convinced Kruger that Great Britain intended to take the Transvaal by force. During the next few years tension mounted and when the British refused to stop military preparations, the Boer republics declared war. Kruger was probably encouraged to expect foreign aid because the German Kaiser had sent him a telegram of congratulations when Jameson’s raiders were captured.

The Boer War surprised the world. Few would have expected that the Boer ranchers could hold out against Britain’s power for more than a month or two. Actually the Boer War lasted for three years, 1899 – 1902. The Boers were fighting in their own rugged country which they knew thoroughly. They used methods of warfare learned in fighting the fierce African tribesmen and the outdoor life led by the Boers had taught them to ride fast and shoot straight. The British felt such respect for their foes that, when the Boers at last surrendered, Great Britain paid a large sum to rebuild the farmhouses that had been destroyed. Although the Transvaal and the Orange Free State lost their independence and became part of the British Empire, they were soon granted home rule.

Imperialism helped to bring about a new line-up of European powers. Besides causing crises and wars, imperialism added new bitterness to the age-old jealousies between rival powers. Out of these rivalries came a new line-up of European powers.

Germany took the first step. As a result of the Franco-Prussian War, Germany had replaced France as the most powerful country on the continent. In order to secure the German Empire from possible attack, Bismarck made agreements with Austria-Hungary and Italy. These agreements, which were completed by 1882, bound Germany, Italy and Austria-Hungary together in the so-called Triple Alliance. According to its terms, if any of these three powers was attacked, the others were to come to its aid.

France in turn sought friends and in 1891 made an alliance with Russia. Then in 1904 France and Great Britain came together in a “friendly understanding.” The British government had been alarmed by Germany’s unfriendly attitude during the trouble with the Boers and by Germany’s growing power on the sea and in world trade. So it was that Britain and France, bitter enemies for centuries, were brought together by a common fear of Germany. This fact explains why Britain, which nearly came to blows with France over possession of the Sudan in 1898, firmly backed France against Germany in the two Moroccan crises a few years later.

In 1907 Great Britain and Russia reached a similar “understanding.” This completed the so-called Triple Entente. (Entente, is a French word meaning “agreement.”) Now two groups of powers — Germany, Austria-Hungary and Italy on one side and France, Russia, Great Britain on the other — faced each other. This new line up of nations was to prove important in both European and world affairs.

3. How Did Imperialism Affect the African?

The carving up of Africa more than fulfilled the wildest hopes of the European countries that acquired colonies. The value of trade between mother countries and colonies first doubled and then tripled during the late 1800’s and the early 1900’s. Great quantities of gold, diamonds, zinc, lead, phosphates, rubber, palm oil and tropical woods flowed from the once unknown continent. Europe’s exports of manufactured articles to Africans zoomed. The opening up of Africa also resulted in the building of railroads, docks and dams. Businessmen at home and their many representatives in Africa prospered from these activities. The European governments — and their tax payers — were less fortunate, however, for the cost of getting and maintaining colonies tended to exceed the public revenue that they brought in.

What about the native peoples of Africa? How did they fare under imperialism? The same questions have been raised about the people of India, China, the Pacific, the Balkan Peninsula of southeastern Europe and Latin America. Wherever the strong hands of imperialistic-Western nations reached, they left their imprint for good and for bad. What happened in Africa illustrates this fact.

Europeans differed in their attitude toward native peoples. Some Europeans viewed the opening up of less advanced countries as an opportunity to aid people less fortunate than themselves. Missionaries, both Catholic and Protestant, felt a strong desire to convert Africans to the Christian religion. Missionaries wanted also to heal the sick and to help spread knowledge. In addition, there were people who sincerely believed that so called “backward peoples” in other parts of the world would benefit by adopting Western ways of living. It was not only the privilege but the duty of the more advanced nations, these people argued, to take over and Westernize less advanced peoples, even though the latter were reluctant to change their way of life. This point of view was well expressed by the British poet Rudyard Kipling in the following stanza of “The White Man’s Burden”:

Take up the White Man’s burden —

And reap his old reward:

The blame of those ye better,

The hate of those ye guard —

The cry of hosts ye humor

(Ah, slowly!) toward the light: —

“Why brought ye us from bondage,

“Our loved Egyptian night?”

W. S. Blunt, another poet of the time, remarked that “the ‘White Man’s Burden’ is the burden of his cash!” It cannot be denied that while some people were moved by unselfish motives, most Europeans went to Africa to get and not to give, to take and not to help. They used native peoples and resources for selfish purposes. Moreover, even the best intentions did not prevent harmful blunders.

Imperialism forced changes. One of the biggest problems created by empire building was that of sudden change. In Africa at the end of the nineteenth century there were more than 100 million people. Some were hunters, herdsmen and farmers still living almost Stone Age lives. Others, particularly in the Moslem states of North Africa, were far more advanced and looked back on their own traditions of past greatness. For all, European imperialism meant a decided break with former ways of life.

Tribes were broken up and scattered. In our country in the nineteenth century, settlers moving westward pushed the Indians before them. The Indians resisted, and a series of Indian wars resulted. In the end, however, the Indians were driven from their hunting grounds and sent to live in special areas called reservations. In Africa, Europeans sometimes fought wars with native tribesmen to break up the tribes and thus reduce the dangers of uprisings. When native peoples were defeated, the survivors were sent to reservations as in North America. This broke down the leadership of heads of tribes and made Africa easier to conquer and to control.

To those who charged imperialistic leaders with needless bloodshed and cruelty, a British statesman in 1897 replied in these words:

You cannot have omelettes without breaking eggs; you cannot destroy the practices of barbarism, of slavery, of superstition, which for centuries have devastated the interior of Africa, without the use of force; but if you will fairly contrast the gain to humanity with the price which we are bound to pay for it I think you may well rejoice in the result of such expeditions as those which have recently been conducted. . . . We may rest assured that for one life lost a hundred will be gained and the cause of civilization and the prosperity of the people will in the long run be . . . advanced.

Many people, including the Africans, would not agree with this point of view. In the long run, however, there was more peace and order among the African people under foreign control than before.

Growth of industries brought Africans to towns. As gold, diamond and copper mines were opened up and as industries and plantations developed, more and more natives went to work for Europeans. They crowded into the towns and cities which grew up near the mines, plantations and factories. Problems of housing and sanitation developed as they had in industrialized countries in other parts of the world.

Africans were not treated as equals. In general, Europeans in Africa regarded themselves as superior to native Africans. Occasionally, in colonies where there were few Europeans, wealthy native Africans might be welcomed socially, but this was the exception. In regions where considerable numbers of Europeans settled, Europeans made and enforced strict laws to keep the two races apart. The importation of workers from India also added to racial differences in Africa.

Native Africans were seldom allowed political rights. When the Boers of South Africa talked of “Africa for the Africans,” these Dutch farmers were talking about themselves. Eventually, when South Africa became united, it was a union for whites, not for the Negro people who lived there. The rest of Africa, except Liberia and Ethiopia, was under European control. The idea that native Africans might govern themselves was unheard of until recent years.

Education was neglected. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries little was done to give native Africans any schooling. Few of them could read or write. In the German colonies, for example, what schools there were met the needs of only a few hundred African students among hundreds of thousands. In Britain’s Cape Colony (at the southern tip of Africa) in 1891 less than half of even the 99,000 European boys and girls attended school. There was no such thing as compulsory schooling for them, to say nothing of any kind of schooling for native African Children. Only a few native Africans received advanced training to help them become leaders among their own people.

There were bright as well as dark sides to imperialism in Africa. Nevertheless, empire building in Africa brought some benefits. The slave trade was abolished and tribal warfare reduced. The development of Africa’s rich natural resources was begun. Medical science helped check tropical diseases. The natives learned a little about sanitation and some hospitals were opened. Moreover, as one observer puts it, the Europeans “may have ravaged a continent, but also they opened it up to civilization. They . . . gave natives only an inch away from barbarism stable administration and a regime based in theory at least on justice and law. . . . Most important, they brought Christianity and western education. Not much education, but some. And there had been none before.”

Progress, however, was painfully slow. Africa was so vast and such great needs existed among so many people that the good effects of the coming of Europeans were often outweighed by the bad. In spite of the efforts of unselfish missionaries, doctors and teachers, most Africans continued to follow primitive ways of living, and most of Africa remained a “dark” continent up to the time of World War II.