Although the cold war was the most important fact in the politics of the post-war world, few persons could have foreseen that it would lead to fighting in the small, remote country of Korea. Yet, as small and remote as it was, Korea had a strategic location. It was near three large powers — Russia, China and Japan — and the Japanese said it “points like a dagger at the heart of our country.”

The Japanese won control of Korea in the Russo-Japanese War and by 1905 they ruled it as part of their empire. During World War II, the Allies promised that “in due course Korea shall become free and independent.” When Japan surrendered, they agreed that Russian troops would occupy Korea north of the thirty-eighth parallel and American troops would occupy Korea south of the thirty-eighth parallel. A provisional government would then be set up and after a period of no longer than five years, Korea would govern itself as an independent nation.

The occupation of Korea was carried out as it had been planned, but the United States and the Soviet Union could not agree on a provisional government. Each set up a provisional government friendly to itself and in 1947 the United States brought the dispute before the United Nations General Assembly. The Assembly decided to hold elections in Korea, but the Soviet Union refused to allow United Nations representatives to enter its occupation zone.

Elections were held outside the Russian zone and in 1948 the Korean Republic was established in South Korea. The city of Seoul was made the capital and Syngman Rhee was elected president. Thirty-two nations, including the United States, recognized the new government; the Russians and “their supporters did not. Instead, the Soviet Union helped to set up a new and separate government in North Korea. It was called the Democratic Peoples’ Republic and its capital was Pyongyang. By 1949, both the Soviet Union and the United States had withdrawn their troops‚ but the country remained divided and the two rival governments faced each other across the thirty-eighth parallel. North Korea and South Korea each had its own army. In North Korea, the Russians had trained about 200,000 men and supplied them with tanks, planes and other equipment. The army of South Korea was considerably weaker.

The government of North Korea was dominated by Communists; the government of South Korea was supported by the United States and its Western allies. Perhaps, with two such opposing governments, an open clash was bound to come sooner or later. Perhaps the Russians, wishing to see all of Korea under Communist rule, advised the North Koreans to attack. The facts were never revealed, but early on Sunday morning, June 25, 1950, North Korean troops crossed the thirty-eighth parallel, using planes, tanks and artillery they had received from the Soviet Union.

When news of the attack reached the United States that same day, President Truman acted quickly. He said that “the United States must do everything within its power, working as closely as possible with the United Nations, to stop and throw back this aggression.” That afternoon, Trygvie Lie, the Secretary General of the United Nations, called a meeting of the Security Council. Before the day was over, the Council had passed a resolution which stated that the attack by North Korea was “a breach of the peace.” It called for an immediate stop to the fighting and the withdrawal of North Korean forces to the thirty-eighth parallel. The Council also asked all members of the United Nations to give “every assistance to the United Nations in the execution of this resolution and to refrain from giving assistance to the North Korean authorities.” The vote on the resolution was nine to nothing; Yugoslavia abstained and the Russian representative did not attend the meeting.

The North Korean forces were not withdrawn. The fighting went on and on June 26 the United States ordered its navy and air force to give support to the South Korean army. The next day the United States introduced a resolution at the United Nations calling for the use of force to bring back peace to Korea. The resolution was passed; it asked member nations of the United Nations to “furnish such assistance to the Republic (the South Korean government) as may be necessary to repel the armed attack and to restore international peace and security in the area.”

When the United States asked the Soviet Union to “use its influence with the North Korean authorities to withdraw their invading forces,” the Russians refused. They blamed the fighting on the South Korean government and “those who stand behind its back.” Together with its satellite nations and Yugoslavia, the Soviet Union charged that the United Nation’s action was illegal. This did not stop the United Nations Council from setting up, on July 7, a unified command of all United Nation forces in Korea. It asked the United States to name a commander and President Truman appointed General Douglas MacArthur to the post. Before the fighting ended, a number of nations would send aid to South Korea. From Britain, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, the Netherlands, Belgium, Colombia, Ethiopia, France, Greece, Luxemburg, the Philippines, South Africa, Thailand and Turkey would come combat troops to join the Americans and the South Koreans. From India, Italy, Norway, Denmark and Sweden would come hospital units.

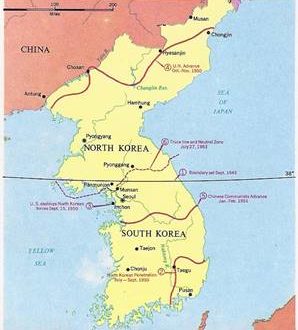

Before the United Nations forces could reach Korea, the Americans and South Koreans were thrown back to a beachhead forty miles wide and ninety miles long. It was at the southeastern end of Korea, near the port of Pusan. The American and South Korean troops managed to hold on and on September 15, 50,000 United States marines and infantrymen landed at Inchon on the west coast. They went on to capture Seoul and by October 1 they had pushed the North Koreans back across the thirty-eighth parallel.

The United Nations command now had to decide whether or not to send troops northward across the thirty-eighth parallel. If it did, China might come into the war and this could lead to another world war. If it did not, North Korea might reorganize its forces and attack again. The United Nations command finally decided to cross the thirty-eighth parallel and MacArthur gave orders for the invasion of North Korea. This time it was the North Koreans who gave way. Before the end of November the United Nations forces had taken Pyongyang, the North Korean capital and advance units had reached the Yalu River, which forms the border of North Korea and China. On November 24 General MacArthur announced an offensive meant to end the war and it seemed as though the fighting would soon be over.

Again events took an unexpected turn. The Chinese Communists sent thousands of troops to the aid of the North Koreans — so many that by the middle of January, 1951, the United Nations forces had been pushed back about seventy-five miles south of the thirty-eighth parallel. Throughout the winter and spring of 1951 there was hard and bitter fighting, with first one side advancing and then the other and casualties were heavy on both sides.

At the same time, a disagreement arose between General MacArthur and President Truman. MacArthur wanted to carry the war to the enemy and win a decisive victory. He wanted to drop bombs on Manchuria and China, perhaps even atomic bombs. He wanted to blockade the coast of China and use Chiang K’ai-shek’s Nationalist troops against the Chinese Communists. President Truman, on the other hand, feared that such action might lead to world war. His policy was to contain the Communists and keep the war a limited one, so that it would not spread beyond Korea. On April 11, 1951, be removed MacArthur from his command and replaced him with General Matthew B. Ridgeway.

The war continued, but it became increasingly clear that both sides were willing to discuss a settlement. On July 10, 1951, negotiations for a cease-fire agreement began. For months the negotiations dragged on, but at last, on July 27, 1953, a cease-fire agreement was signed and the fighting stopped. About 1,474,269 men of the United Nations forces were dead, wounded, captured, or missing. South Korean casualties were 1,312, 836; American casualties 144,173. Communist casualties were estimated to be 1,540,000.

Korea remained a divided nation, but the United Nations had shown that it could take effective action against aggression and the Korean conflict had not led to another world war.