If you are fortunate enough to visit eastern Canada, undoubtedly you will wish to include the city of Quebec in your travels. Quebec is perched on the sides and the summit of a steep, rocky promontory overlooking the St. Lawrence River. With narrow, winding streets and French speaking population, the city is a reminder of past centuries when France controlled much of what is now Canada.

On September 13, 1759, on the plain outside Quebec, was fought one of history’s decisive battles. For several years English and French forces had been battling in North America, but neither side had been able to defeat the other. Montcalm, the French general and his army felt reasonably secure in their natural fortress at Quebec. Finally, however, James Wolfe, a brilliant young English general, worked out a bold plan for making a direct attack on the French stronghold. Wolfe discovered a narrow path leading up the steep cliff from the riverbank. To fool the French he kept the English fleet farther up the St. Lawrence. Then, on the night of September 12, the English soldiers in small boats drifted noiselessly down the river. In the darkness they climbed stealthily up the rocky path. Having surprised the guards at the top of the cliff, Wolfe and his forces at dawn were ready for battle.

The French forces inside the city were short of provisions. Although his men were poorly trained, Montcalm led them out of Quebec to meet the English. The French were no match for Wolfe’s well-disciplined troops.

At the height of the battle, as the English swept toward Victory, Wolfe received a fatal wound. A famous historian has given us the following report of Wolfe’s last moments.

“They run! They run!” cried one of the soldiers who were carrying the stricken general from the battlefield.

“Who run?” asked Wolfe.

“The French,” was the reply.

“Now, God be praised! I die in peace” were Wolfe’s last words.

This brief account of the Battle of Quebec may well cause you to ask why the battle was important and what it has to do with world history. Compared with battles of modern warfare, this one at Quebec was small. Fewer than 5000 men were engaged on each side, but the results of the battle were important. The English victory meant (1) that England, not France, would become the world’s greatest colonial power; (2) that English, not French, would become the language used by the greatest number of people in North America; and (3) that English ideas of free government, not French notions of unlimited royal authority, would have a chance to develop on our continent.

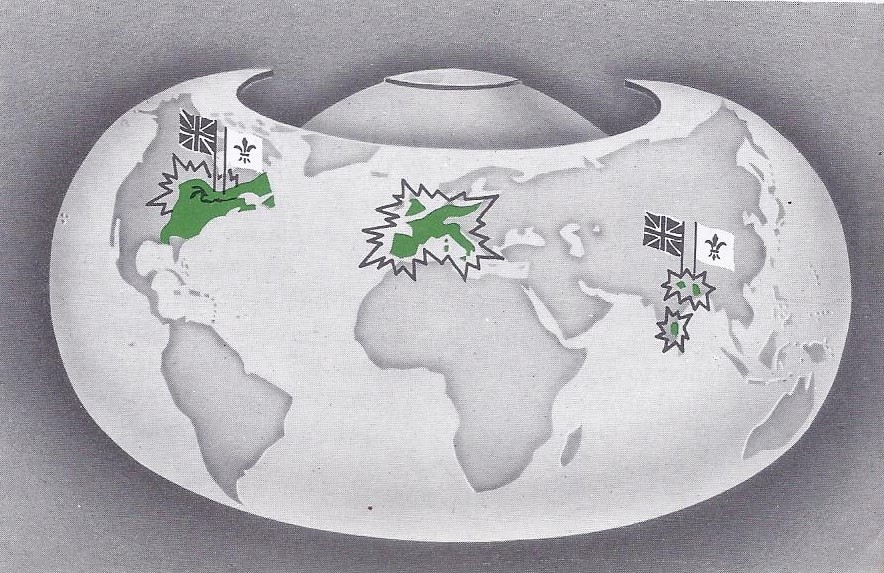

Furthermore, the war of which the Battle of Quebec was the turning point was part of a world-wide conflict — a conflict fought in Europe, in Asia and on the seas as well as in the New World. What happened in each of these widely separated parts of the world affected the outcome in the others.

In this chapter you will learn about the growth of the French and English colonies in North America and in India. You will learn more about the struggle for empire between England and France. You will learn how European rulers plotted, fought and shifted sides in this world struggle. In brief, you will find answers to these questions:

1. What attracted settlers to the English colonies?

2. In what ways did the French colonies differ from the English?

3. How were the European struggles of the 1700’s related to colonial wars?

4. How did the English overcome the French in India and in North America?

1. What Attracted Settlers to the English Colonies?

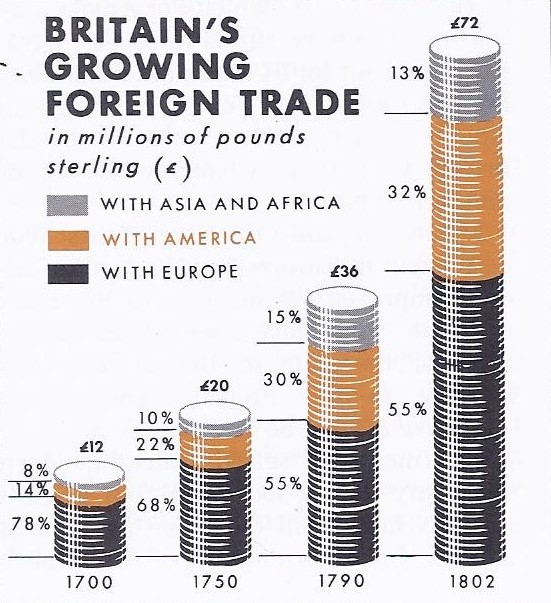

Geographical position helped England in the race for colonies. We have already read that the English entered the race for colonies later than the Spanish and the Portuguese. Once the English had started, the fact that they lived on an island proved a considerable advantage. During the 1600’s and 1700’s they were able to keep out of several of the long and destructive wars on the continent of Europe which weakened such powers as France, Spain, and Austria. Their island surroundings and seafaring traditions led the English to build a strong navy and merchant fleet. Strength on the seas enabled England to acquire a large colonial empire. Like an alert football back who recovers a rolling ball for his own side while other players are piled up in a scrimmage, the English made the most of opportunities which other nations were not free to seize to their own advantage.

Private enterprise built England’s colonies in America and India. The discovery of the New World and the opening of new trade routes led to the formation of trading companies. The stockholders of these companies furnished the needed money and shared in the profits of colonising and trading ventures. During the 1600’s the English government left the work of colonial settlement in large part to such trading companies. England, for example, gained a foothold in India through the business activities of the British East India Company. It was the London Company that sent over the settlers who in 1607 founded Jamestown, the first permanent English colony in North America. Some of the New England settlements were established by the Plymouth Company and the beginnings of English rule in northern Canada grew out of the fur-trading activities of the Hudson’s Bay Company. In all these cases, private citizens eager for profits sent trading ships to the Orient or colonists to the New World. In short, private enterprise was at work.

Jamestown was an example of a trading-company settlement. Colonising the New World was an uphill struggle, as illustrated by the experience of the London Company’s settlement in Jamestown. The early years at Jamestown were disappointing. There was none of the hoped-for gold such as the Spaniards had found and there was not much fur. Most of the settlers were ill prepared for the difficulties and dangers of pioneer living. At one time the settlement was almost abandoned. Then came new settlers and the discovery that a profitable trade could be developed in tobacco. The colony forged ahead as new settlements spread out from Jamestown and the entire region was named Virginia. Settlers were allowed to choose representatives to a House of Burgesses, which helped the governor and his council make laws. In time Virginia became a royal colony, subject to the king rather than just the venture of a trading company, but even under royal control the House of Burgesses continued to meet.

Some colonies were founded by proprietors. Not all English settlements in North America owed their start to trading companies. English kings granted huge tracts of land to certain nobles known as proprietors, either as favours or in payment for services. Maryland, Pennsylvania and the Carolinas began in this way. Sometimes kings were more generous than careful, with the result that land grants overlapped. The boundaries of their grants of land and the extent of their governing powers were written down for both trading companies and proprietors in official documents known as charters. These colonial charters help to explain why Americans later thought it important to provide written constitutions for their states and for the country as a whole.

Oppressed people sought freedom in the New World. Europeans had various reasons for settling in the English colonies in America. For one thing, during the 1600’s and 1700’s, as in later times, America offered hope to oppressed people of the Old World. Some courageous men and women made the long ocean voyage to America rather than submit to the harsh rule of kings. Many more came because their religious beliefs and methods of worship differed from those of the established church of their homeland. In brief, many people sought in America freedom which they could not have in Europe.

For example, the Pilgrims who settled in Plymouth, Massachusetts had come to America to obtain religious freedom. So had the settlers, called Puritans, who founded other settlements in and around Boston. The Puritans were unwilling to extend the same right of religious freedom to people who disagreed with them. They drove Quakers and Baptists out of Massachusetts. In fact, the Puritans’ intolerance led a young minister, Roger Williams and other colonists to flee from Massachusetts and to found settlements in Rhode Island.

Other groups also sought religious freedom in the English colonies. There were Quakers from England, most of whom settled in Pennsylvania. Oppressed Catholics from England settled in Maryland, which Lord Baltimore established for this purpose. Huguenots fleeing from France sought new homes in several of the American colonies. People of the Jewish faith also settled in the growing colonial cities and towns. Smaller numbers of religious refugees came to America from other countries, too.

Hard times brought thousands to the English colonies. The difficulty of making a living caused many to come to America. English landowners, eager to make money by raising more sheep for the rapidly expanding wool market, changed farms into pasture land. Many English farm labourers, therefore, lost their homes and their jobs. To these unemployed, the promise of cheap and plentiful land in the colonies offered a new start in life. Many a poor man willingly bound himself to work for several years in the colonies to pay for his passage across the Atlantic. Such workers were called indentured servants.

Among others who sought to better themselves by going to the English colonies were Germans who had suffered from the destructive wars of the 1600’s and 1700’s. There were also the Scotch-Irish (people from northern Ireland), many of whom braved the dangers of the wildermess to build new homes.

It would be wrong, however, to think that all colonists came to escape hard times or to seek religious freedom. In England property and rank were ordinarily inherited by the oldest son, younger sons of wealthy families felt they could better themselves overseas. Merchants and traders were eager for profits. Professional men (doctors, lawyers, and clergymen) sought new opportunities. The spirit of adventure attracted many restless persons to the New World. Thousands of Negroes, however, were brought over by slave-traders.

English colonial settlements spread. Hunger for land not only led immigrants to the English colonies, but also kept them on the move after they had arrived. Many settlers were not satisfied with the farm lands they had cleared in the forests near the seacoast, they found their way inland by following the courses of the rivers.

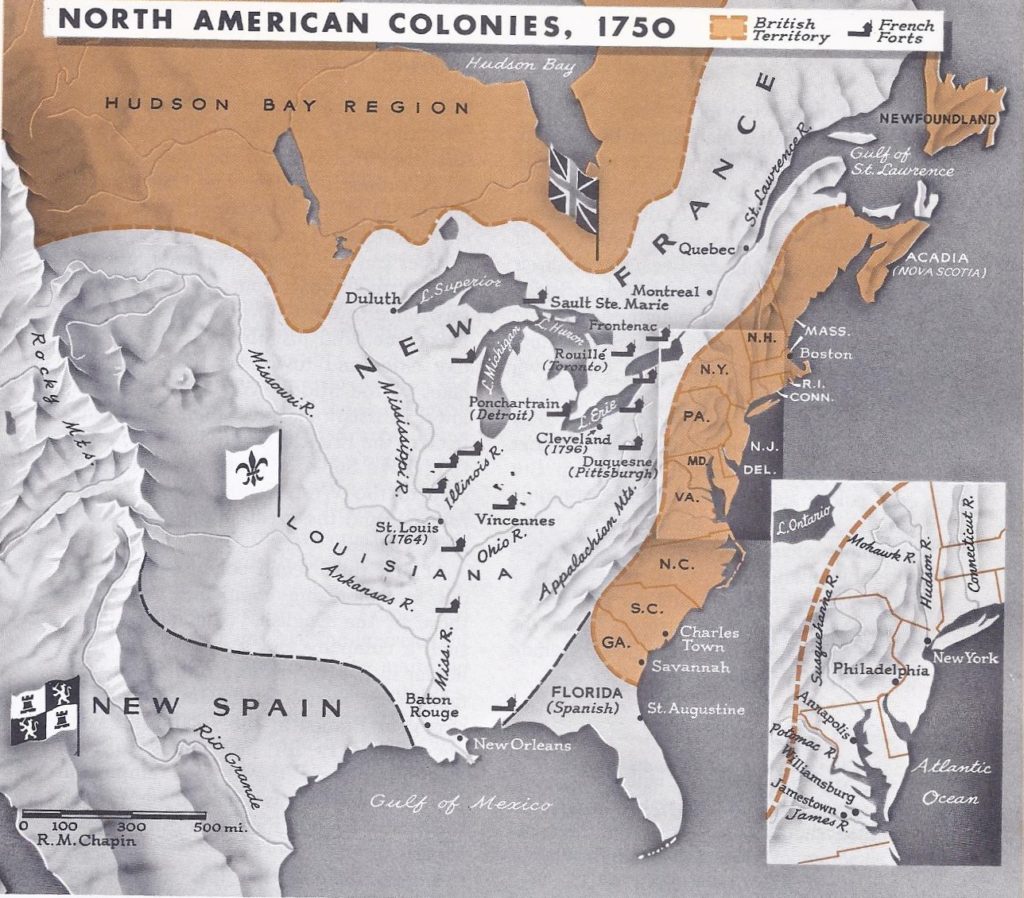

In New England, for instance, the Connecticut River provided a water route northward into present-day New Hampshire and Vermont. In New York, the Hudson and Mohawk Rivers formed another such route northward and westward. In Pennsylvania, pioneers pushed westward by way of the broad Susquehanna River, while farther south the Potomac and James Rivers led settlers inland. By 1700, the English colonies in North America reached from the Atlantic Ocean to the eastern slope of the Appalachians. Some pioneers had even crossed that mountain barrier into the Ohio and Mississippi valleys, which the French claimed as their own.

New Englanders made a living in various ways. Nine-tenths of the settlers were farmers. In New England, however, a smaller percentage of people made their living by farming than in other sections of the English colonies. In most of New England the ground is stony and the soil is poor So, many New Englanders turned to shipbuilding, trade and fishing.

New England farms generally were small and close together. The farmer and his family shared the farm work, helped sometimes by a hired labourer. These Yankee farmers were jacks-of-all-trades. They built houses and farm buildings and slaughtered cattle and hogs and cured the meat. They tanned leather for shoes and harness and made many of their own farm implements. Their wives churned butter, spun wool, wove it into cloth and made clothing of the cloth and leather besides bringing up large families.

The middle colonies were the “bread colonies.” Farm land in New York, New Jersey, Delaware and Pennsylvania generally was richer than in New England. These “middle colonies” produced not only enough grain and other foodstuffs to supply their own needs but also a surplus for export. Large estates worked by tenant farmers were more common in the middle colonies than in New England, though small farms were the general rule. Among the most successful farmers were the Pennsylvania Germans who had been driven from their European homes by war and hard times. These Germans came to be known as the Pennsylvania “Dutch” thrifty, hard-working farmers whose descendants still work the carefully tended lands of their ancestors.

The plantation system developed in the South. The fertile soil and mild climate of the South were particularly favourable to agriculture. There were many large farms called plantations, where tobacco, indigo, and rice were grown for export to England. Many a plantation owner became rich and lived on a lavish scale, but he had to depend on indentured servants and slaves to work on his plantation.

In the South there were also many owners of small farms, who raised tobacco and other crops. Sometimes they had a few slaves. West of the cleared farm lands of the middle and southern colonies were hardy frontiersmen. They formed an advance wave of migration into the outlying valleys and slopes of the Appalachian Mountains. Some of these restless frontiersmen, many of whom were Scotch-Irish, found passes through the mountains and ventured into the present day states of Ohio, Kentucky and Tennessee.

Colonial towns and cities grew. By 1750, more than 1.5 million people (roughly the present population of Cleveland, Ohio with its suburbs) lived in the thirteen colonies along the Atlantic seaboard. By no means did all the colonists lived on farms. Such towns as Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Annapolis and Charleston (or Charles Town as they called it in those days) were busy places, though they were small in comparison with present-day American cities. From these lively centres merchants sent ships loaded with lumber, tobacco, furs, fish, wheat and corn to England and to other English colonies. Back came the vessels carrying goods the settlers wanted: cloth, furniture, fine dishes, coffee, tea, articles made of iron and steel, and books.

Life in the colonies had distinct advantages. As the colonies increased in population, many of the dangers and difficult ties experienced by the early settlers tended to disappear. In fact, settlers in the English colonies found that in many ways they were better off than people in the mother country. In England a poor man rarely owned land, almost never could vote and usually had received no formal schooling, but a poor man in the English colonies could acquire a farm fairly easily; often by just clearing the land. If the settler owned land, he usually won the right to vote, for even in the colonies men without property seldom had this right. Opportunities for schooling varied widely from colony to colony and from the towns to the farm areas. For the poor man, they were usually better than in Europe. In addition to schools and colleges, lending libraries had appeared and weekly newspapers were published in most of the colonies.

Laws in the colonies were often less harsh than in the mother country. In England there were more than a hundred crimes for which a man might be hanged, but in the colonies only a few offenses were punishable by death. In England, such groups as Pilgrims, Puritans, Quakers and Roman Catholics were persecuted at one time or another because of their religious beliefs. In such colonies as Rhode Island and Maryland religious freedom came much earlier than it did in England.

Finally, the colonists ran their own affairs to a considerable degree. They were, to be sure, subject to the English king and Parliament. Governors and other colonial officials represented the king, but each colony had its own elected assembly which, among other things, voted taxes. On more than one occasion a colonial assembly made a royal governor squirm by refusing to vote funds for his salary. Control of the purse strings made the American colonists increasingly self-reliant and ready for independence.

2. In What Ways Did the French Colonies Differ from the English?

France built an empire in North America. While England’s colonies in North America had been growing, the French, too, had been busy. We have already read about the chain of trading posts and forts they had built all the way from the St. Lawrence River to New Orleans near the mouth of the Mississippi River. With easy portages (places where boats and cargoes can be carried overland), one can go by small boat from the Gulf of St. Lawrence to the Gulf of Mexico. Daring Frenchmen did just that. Many presentday cities and towns on the rivers and lakes of the Middle West and along the lower Mississippi trace their beginnings back to the French. There is Duluth, bustling Lake Superior port; St. Louis, gateway to the West; Baton Rouge; and the great shipping centre of New Orleans.

At first the French colonists were sent out by colonising companies much like those of the English. (Richelieu started such a company and was a heavy stockholder in it.) Soon these companies were taken over by the kings, for kings were strong in France in the 1600’s and were always hungry for new lands to rule. Headquarters of the French empire in North America was Quebec on the St. Lawrence River. Farther upstream was Montreal.

French colonists led less settled lives than the English colonists. The great majority of English settlers, as you know, farmed the land. In New France, however, except for a small number of farmers in the St. Lawrence valley and along the coast, most of the settlers were priests, trappers, traders and soldiers. The very nature of their work kept such people on the move. Many of the explorers of the inland areas were priests who went out to convert the Indians. Up the broad St. Lawrence daring explorers paddled in canoes and then followed the Great Lakes to the West. From rivers running into the Great Lakes they found their way to the Ohio, Illinois and Mississippi Rivers.

One of the most adventurous explorers, La Salle, was not a priest but a trader. It was La Salle who, standing near the mouth of the Mississippi River, claimed for his king all the lands from which water flowed into that mighty river and its branches — all the land between the Appalachians and the Rocky Mountains. Had La Salle not been murdered by one of his men, he might have become the royal governor of the entire basin drained by the Mississippi, a realm several times the size of France.

New France grew more slowly than did the English colonies. By 1750 the English lived in fairly thickly settled areas along the Atlantic coast, while the French were scattered thinly over a vast area. In all, the population of New France totaled about 80,000, only one-twentieth as large as that of the English colonies.

There were several reasons why population grew slowly in New France. (1) The government in France limited settlers on the mainland of North America to French Catholics. (2) French settlers were forced to live under strict control. French colonists had to obey the king’s governor in all matters. Farmers along the St. Lawrence could not own land but were obliged to work on huge estates somewhat like the feudal manors in Europe. New France, in other words, did not offer settlers the opportunities for a freer and better life that the English colonies did. (3) Trappers and fur traders were less likely to build permanent settlements than were farmers.

French and English interests in North America clashed. Huge though North America was, it was not large enough to prevent the French and English from clashing. Each nation’s first permanent colonies in America were founded within a few years after 1600. Both claimed the same tertitory — all of eastern North America. Each was determined to expand at the expense of the other. By about 1750 rivalry became bitter, for English frontiersmen were spilling over into the Ohio valley which the French had already claimed. And this natural rivalry between English and French colonists was made stronger by rivalries between the two mother countries in Europe.

3. How Were the European Struggles of the 1700’s Related to Colonial Wars?

Developments in North America were closely related to events in Europe. The rivalry which sprang up between the English and the French in North America was closely tied in with European wars and politics. In previous chapters of this unit you have learned how kings engaged in wars to gain territory and power. You will remember that England joined other countries in the War of the League of Augsburg and again in the War of the Spanish Succession to prevent Louis XIV from upsetting the balance of power in Europe. What is equally important, each of these European contests was paralleled by a colonial war between England and France. Even before 1700, then, a world wide struggle for power between England and France had begun. The Timetable out lines this century long conflict.

After the death of Louis XIV in 1715, an uneasy peace prevailed in most of Europe for about twenty-five years. Then, between 1740 and 1763, two great European wars were fought — the War of the Austrian Succession and the Seven Years’ War. Both wars grew out of the ambitions of the rulers of Prussia and Austria. In each, as had become usual, France and England fought on opposite sides. Although the fighting spread beyond Europe each time, France concentrated its efforts on the continent. England, with its larger fleet and larger overseas population, was able to fight victoriously both in North America and in India.

Ambitious rulers brought about the War of the Austrian Succession. The coming to the Austrian throne of a new ruler in 1740 was the signal for war to break out again among the countries of Europe. This new ruler was Maria Theresa, the daughter of the Hapsburg ruler of Austria who was also the Holy Roman Emperor. Her father, Emperor Charles VI, had been troubled because he had no son to succeed him. In those days, according to established law and custom, a woman could rule over some Hapsburg countries, but over others only a male could rule. To make sure that his daughter would inherit all the Austrian lands, Charles VI had consulted with the rulers of the other great European powers. They had agreed to offer no objections to Maria’s rule. The Emperor died believing in his trusting heart that these monarchs would keep their promises, but the temptation to snatch territory from young Maria Theresa was too great to resist.

For example, the King of Bavaria, who had signed no agreement with Charles (as if that would have made any difference!), wanted to be both ruler of Austria and Holy Roman Emperor. The King of France, Louis XV, felt that the time was ripe to seize the Austrian Netherlands (Belgium). Frederick II of Prussia ( who came to be known as Frederick the Great) desired the Austrian province of Silesia which lay temptingly close to his lands. Frederick had some old claims to part of Silesia, and offered to side with Austria if these were recognized. When his claims were rejected, Frederick ordered his troops into Silesia. In 1740, then, Europe was plunged into a general war called the War of the Austrian Succession.

The War of the Austrian Succession caused few changes. The rulers of France, Spain and the German states of Bavaria and Saxony joined Frederick of Prussia in attacking Austria. England and Holland sided with Maria Theresa. The European conflict spread to America, where the French and their Spanish allies clashed with the English. To the surprise of all, Maria Theresa gallantly defended her lands. When peace was declared in 1748, Maria Theresa had lost only Silesia, which Frederick had seized early in the war. In America, both sides returned what they had taken from each other.

Maria Theresa sought revenge on Frederick the Great. Maria Theresa had gained military honour in the war and was proud that her husband, Francis of Lorraine, had been elected Holy Roman Emperor. She however, felt disgraced because Austria had lost Silesia to a smaller power. Her chief ambition was to defeat Frederick and to regain her lost territory.

To accomplish this purpose Maria Theresa set out to build up a powerful alliance against Prussia and she was most successful in her scheming. Within the space of a few years France, Russia, Spain, Saxony and Sweden became the allies of Austria. You will notice that this list includes several countries which had fought with Prussia, against Austria, in the War of the Austrian Succession. The strangest part of this alliance was that Bourbon France and Hapsburg Austria, usually enemies, were now allies. Meanwhile England made a treaty with Frederick, agreeing not to fight against Prussia in any wars in which Prussia might be engaged.

The Seven Years’ War followed. Frederick the Great decided not to wait for an attack by the group of nations lined up against him. He struck first, occupying Saxony with his crack Prussian army. So began the Seven Years’ War (1756 – 1763), which in America was the French and Indian War.

Few men have faced such odds as Frederick. Only the English and a few German states were on his side; and the English, who were thting on the seas and in the colonies, could give him littlemore than money. Frederick’s superbly trained troops hurled themselves in turn against Russians, Swedes, Austrians, and French. Nevertheless for a while it seemed that Prussia must be overcome.

Then when the pressure was greatest, chance saved Prussia and Frederick from defeat. His bitter enemy, Elizabeth the ruler of Russia, died and the new ruler made peace. Bit by bit, the alliance which Maria Theresa had built to destroy Frederick fell apart. When Austria and Prussia made peace in 1763, Silesia was still in Frederick’s hands. During the years of peace which followed, Frederick built Prussia into one of the leading states of Europe. Meanwhile England had emerged from the colonial wars, master of India and of North America.

TIMETABLE – A CENTURY OF WORLD CONFLICT (Colonial Wars)

War of the league of Augsburg, 1689-1697

In North America: King William’s War between England and France. No important gains.

War of the Spanish Succession, 1701-1713

In North America: Queen Anne’s War.

France and Spain against Britain.

Britain gained Acadia (Nova Scotia).

War of the Austrian Succession, 1740-1748

Prussia and other German states, France and Spain against Austria, Britain and Holland, ( In North America; King George’s War. Britain against France.)

Concluded by Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle. No gains except Silesia to Prussia.

Seven Years’ War, 1756-1763

Austria, France, Russia, Spain and Sweden against Prussia, aided by Britain.

(In North America: the French and Indian War, 1755-1763, between France and Britain. In India: Britain against France.) Concluded by the Peace of Paris. In Europe: no important territorial changes. In North America: Britain gained New France and Florida. In India: British influence largely replaced French.

War of American Independence, 1775-1783

In North America: the British colonies that became the America’s thirteen original states, aided by France and indirectly by Spain and Holland, against Britain. Results: independence of the United States, British loss of Florida and minor islands in the West Indies. Concluded by a Treaty of Paris.

4. How Did the English Overcome the French in India and in North America?

While Frederick the Great fought Austria and its allies in Europe, England and France waged war on the high seas, in India, along the frontier of the English colonies, and in New France. England won Final victory in this struggle largely because William Pitt was the statesman guiding its policies. Pitt realized that England’s real interest lay in the colonial struggle rather than in the war on the continent of Europe. He therefore took steps to destroy French sea power and to supply money, troops and able officers for the colonial armies.

Misrule by the Moguls paved the way for control of India by Europeans. To understand what happened in India in this duel between England and France, you will want to recall some earlier events when invaders called Moguls began their conquest of India shortly after 1500. Under Akbar, an outstanding Mogul ruler, India began a period of greatness. Akbar set up a system of just and efficient government. He gave his subjects religious freedom and encouraged art and learning. Later Mogul rulers, however, were less wise than Akbar. Although they brought most of India under their control, they were extravagant and did not care about the people’s welfare. Eventually they lost their hold over the local rajahs, who quarreled endlessly among themselves. Religious conflict between the Moslems and Hindus also helped to split India apart. This confused state of affairs made it easier for Europeans to gain control of India’s rich trade. In the absence of any strong central government, Europeans were able to make deals with local rulers and obtain positions of authority.

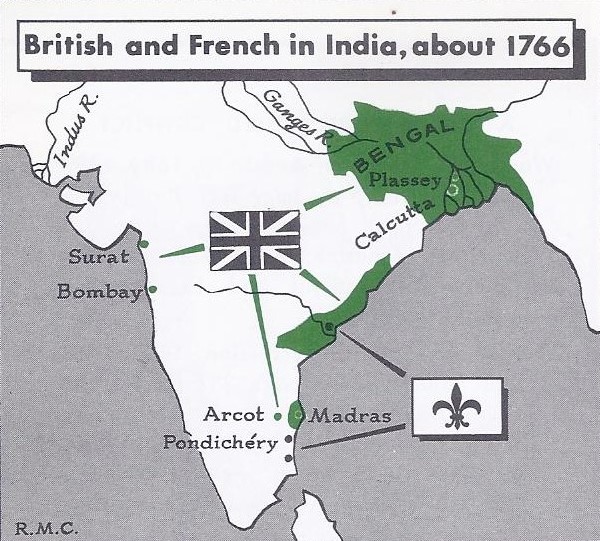

Although the Portuguese had been the first to reach India, they lost much of their former Far Eastern trade to the Dutch and the English. The Dutch established firm control in the Spice Islands. By the late 1600’s English and French trading companies had a foothold in India.

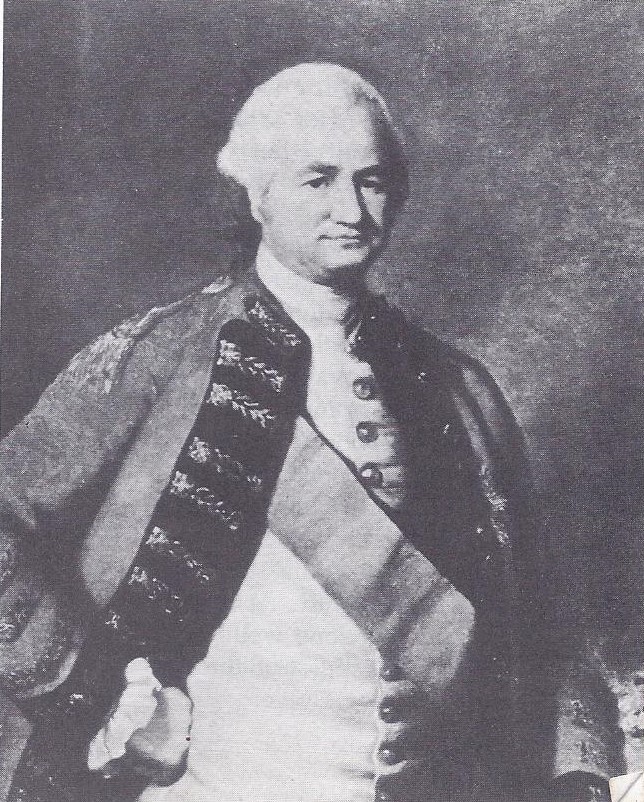

Both England and France became powerful in India. Employees of both the British and French trading companies took advantage of the disorder prevailing in India to increase their own influence. French traders supported some of the quarrelling local rulers, while English traders took sides with others. Finally an able Frenchman named Dupleix managed to win most of the rajahs of southern India over to the French side. Just when the outlook for England was darkest, a young Englishman named Robert Clive came on the scene. Clive had gone out to India as a clerk for the British East India Company and found his job boring. So he transferred to the military branch of the East India Company’s service.

Clive seized control of India. The rest of Clive’s life reads like an adventure thriller. This young, inexperienced civilian set out to defeat Indian rulers supported by the French. Leading a small force of 300 native troops and 200 English, he captured the Indian city of Arcot. In spite of efforts to retake Arcot, Clive held out for 54 days until other EngIish led forces drove off the enemy. In other campaigns Clive soon made the British East India Company master of southern India.

Meanwhile, since the Seven Years’ War had begun in Europe, Englishmen in Calcutta improved the defenses of this trading post. This move angered the Indian ruler of the state of Bengal who was friendly to the French. The nawab, as he was called, gathered 50,000 men and seized Calcutta. Then the angry nawab locked up 146 English subjects in a small cell less than 20 feet square. Next morning 123 of the English were dead of suffocation in what has ever since been called the “Black Hole of Calcutta.”

When Clive heard the news, he led a small army to Calcutta and recaptured the city, but he was also determined to overthrow the nawab, even against overwhelming odds. In the campaign that followed, the nawab’s army was twenty times as large as Clive’s. Nevertheless, Clive destroyed the enemy army on the battlefield of Plassey in 1757. By appointing a new nawab, Clive was able to rule Bengal for the British East India Company.

English control of India was nearly complete at the end of the Seven Years’ War in 1763. This control, however, did not operate directly but was carried out by the East India Company through local rulers. France kept a few trading posts in India, but no forts or armies. Most of India still remained under the native rulers, but they could not stop the English from extending their influence generally throughout the country.

The East India Company was put under government control. The East India Company had been formed merely to carry on trade. As a result of Clive’s victories, however, it faced the job of ruling far more people in India than lived in Great Britain! The British East India Company did not use its great powers wisely. One governor of the company who was accused of dipping his hand occasionally into India’s treasure chests was tried before Parliament. After a long trial he was found not guilty, but it became evident that the task of ruling millions of people so far away from England was too much for the East India Company. In 1784 the East India Company was placed under control of the English government. Though many of the old evils disappeared, the new system was by no means perfect. We learn how India fared under British rule and how it became an independent nation.

The English were victorious in North America. While Clive was driving the French from India, the war in America reached its climax. At the outset the English had not done well. For their failure in the early stages of the war there were three reasons: (1) The separate English colonies did not work together as well as did the parts of New France under direct government control from Paris. (2) Except for the Iroquois, the Indian tribes were firm allies of the French and therefore hostile to the English. (3) The English government at home did not fully realize the importance of the colonial war.

A brave but foolhardy English general named Braddock had marched against the French at Fort Duquesne on the site of the present day city of Pittsburgh and had led his red coated troops into an ambush. The English and colonial troops suffered heavy losses, though fortunately among the survivors was a young Virginia colonel named George Washington. Early in the war the French captured several English forts along the frontier.

Then in 1757 William Pitt came to power in England, and the tide began to turn against the French. Pitt’s energy and confidence inspired a new spirit among the English troops and in the American colonies English forces captured a number of French forts and General Wolfe gained the decisive victory in 1759 which was described at the beginning of this article. A year after Quebec fell, the English took Montreal. Victories, boasted the English, came so fast they could hardly keep up with the news.

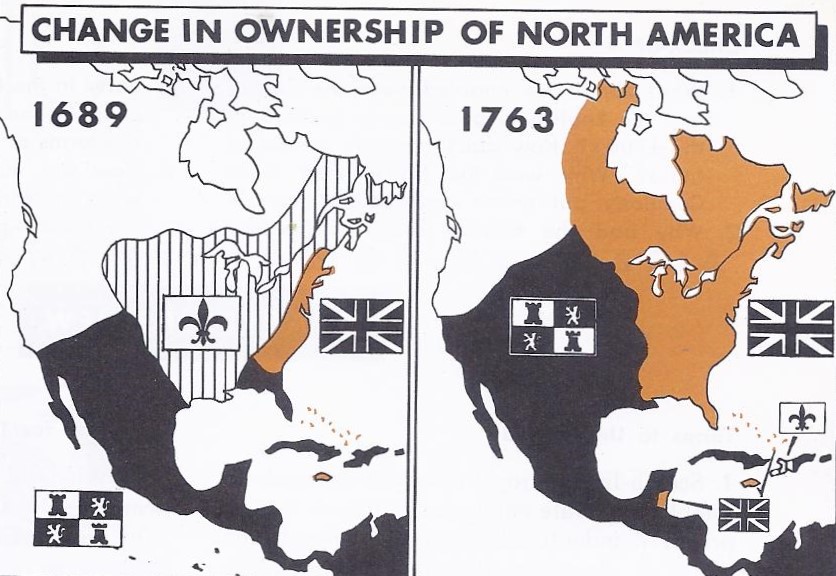

France lost its holdings in North America. The Treaty of Paris in 1763 formally ended the Seven Years’ War. By this treaty France gave up all its North American possessions except a few small islands in the West Indies and in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Spain, which had been an ally of France, gave Florida to England and received the former French lands west of the Mississippi River. The map on this page shows you how ownership of North America changed between 1689 and 1763.

The results of France’s defeat were far-reaching. France’s defeat started a train of important events. For one thing, when General Wolfe won his smashing victory at Quebec, he unknowingly opened the door to American independence. With the French power in North America destroyed, the English colonies felt they could take care of themselves. Later, when the English government sought to force stricter regulations upon them, the colonies objected. The quarrel between England and its colonies finally became so bitter that the American colonies fought for, and won, independence.

A second outcome of France’s defeat was a shift in the standing of the European powers. England became the foremost sea power in the world. The combination of sea power and colonies brought great wealth to England. France, on the other hand, lost most of its colonies. The war increased France’s national debt and put an additional burden on the French people. It also made France long for revenge, which was one reason why France sided with the United States against England during the American Revolution. The French defeat also led toward revolution in France, as we will read going forward.