Across the plains of Peloponnesus, flashed the swift chariots of knights and warrior-princes. They wore armour of gleaming bronze and bright proud plumes bobbed above their helmets. They were the new men of a new country and they called themselves the Achaeans. Their kings called themselves the Sons of Pelops, the mighty chief and hero who had given his name to the Peloponnesus.

Pelops, the Achaeans said, was the son of a god. Probably, however, he was the grandson of an European invader, for many of the Achaeans’ ancestors were barbarian invaders from the north. But they may have seemed like gods to the Shore People when they first hacked their way into the country. Their ragged beards and horned helmets were frightening to look at and they fought like demons, they took the land they wanted, built fortresses and settles down to stay. When Minoan sailor-merchants began to stop at their towns, the warriors went into business, growing olives and squeezing them in presses to make oil. Olive oil was the butter, cooking grease, lamp fuel and hair tonic of the ancient world and the Achaeans began to grow rich.

For a hundred years, from 1500 to 1400 B. C., the Achaean kings built a stronghold at Mycenae, not for from the Isthmus, the strip of land that connected the Peloponnesus to the mainland. The new castle, towering above the plain, had room inside to shelter all the people of Mycenae. Its huge walls looked like cliffs and people said that the stones had been put there by the Cyclops, the one-eyed giants whose parents were the gods of the earth and sky. When the king’s trumpets sounded the warning that an enemy was near, farmers ran from their fields and potters and armourers left their shops at the base of the castle hill. They crowded through the castle gates. Some clutched their children and their most precious possessions in their arms. Others tugged at their animals, for their was space inside the walls for the cattle as well as the people. Food enough for everyone had already been stored on the castle hill, along with the city’s valuable supply of olive oil. A well had been chipped through hundreds of feet of rock to provide a safe supply of water. Once the gates were pushed shut, with millstones and boulders heaped up against them, the king and his people could wait out an enemy siege for weeks or months. They could fight back, too. Soldiers who tried to storm the gates were easy targets for the archers stationed on the high walls. Anyone who tried to climb the wall itself met a deadly rain of rocks and flaming logs or oil. If someone managed to climb up to the top, the defenders were ready with axes to split his helmet and his head.

The defences of the castle were so strong, in fact, that they were seldom used. Enemies stayed away and the strangers who came to Mycenae came in peace. They were given a very different sort of greeting. Every man, when he had spoken his name and sworn that he had come as a friend, was treated courteously. An important visitor – anyone who came in a chariot — was welcomed with ceremony and allowed to drive up the ramp into the courtyard of the palace. He entered by the main gate, where two lions carved from a huge slab of limestone stood guard above the gateway. From the Lions’ Gate he was led across the courtyard, through other strong gateways, to the great front door of the palace.

This building was as splendid as any that King Minos could have imagined. Slabs of gleaming white limestone hid the rocks and wooden posts which gave strength to its walls. The floors, ceilings and walls were covered with paintings and coloured stucco. In the first of the royal chambers, where a guest waited until he was summoned to the throne room, there were soft couches for the visitors. The Achaeans still kept the custom of sleeping in the great hall or megaron; this outer chamber was the palace “guest room”. If the visitor was tired and dusty from his journey, he was offered a bath before he went to meet the king and if he was an important person, he took his bath in the royal bathroom, a large, bright room with an enormous clay tub standing in its centre. Jars of steaming water stood at hand and there were servants to wait on him. There were oils to be added to the baths and perfumes to sweeten it. When the guest was in the tub, he was offered a cup of wine to make him relax. After his bath he was rubbed with perfumed oils.

The Achaeans made the perfumed oil by adding herbs to plain olive oil. The herbs were gathered from the hills, where they grew in abundance. All the people of the Mediterranean loved perfumed oil. The Egyptians made it into a thick cream, which they heaped on the heads of honoured guests at feasts. As the evening went on, the cream would melt and run down their bodies.

So the Achaeans became the oil traders of the world. They sold oil plain in big clay jars or perfumed in delicate, painted vases and it made them rich. Mycenae’s King was a merchant as well as a general and a chief. The deep cellars of his castle were filled with row upon row of oil jars. Dozens of clerks kept records of his collections, shipment and sales. In the little accounting rooms near the entrance, they scratched the daily records on tablets of soft clay with pointed sticks. They also kept lists of the number of his chariots, the movement of his troops, the weapons sent to soldiers in the field, the furniture built for the palace and the supply of golden wine cups. The lists were long, for Mycenae was the richest kingdom in Greece. Oil had paid for it all — the castle walls, the palace and the splendid throne room to which the visitor was led, fresh from his bath.

The throne room remained a megaron, but it was bright with colour and sparkling with jewelled decorations. Delicate patterns of sea animals and grasses wound across the floor and hearth at its centre. The walls were covered with pictures of sacred and magical beasts. The throne itself was a huge wooden chair inlaid with battle scenes worked in gold, silver and tin.

The men who stood about the throne were as different from the barbaric warriors as their megaron was from the hall in the old fortress. The Achaeans had learned more than trading and seamanship from the Minoans. They had shaved off their beards and curled their hair. Like the Minoans, they now wore jewelled belts and short leather breaches.

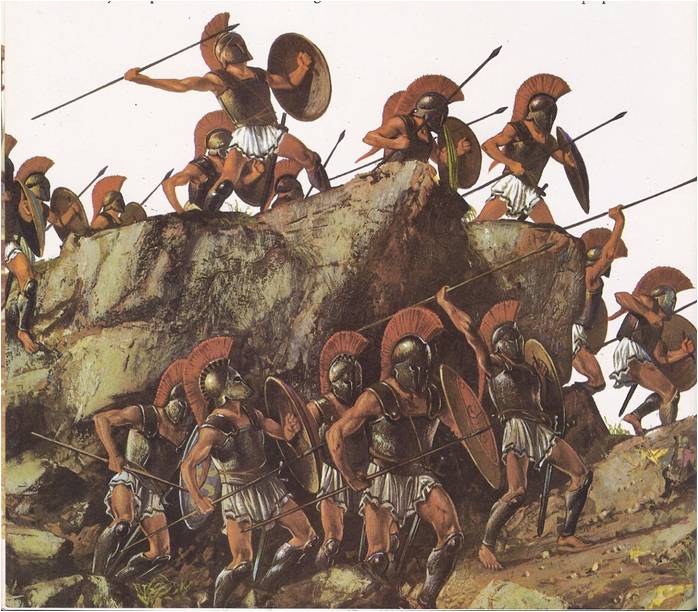

Inspite of their elegant dress, they were still warriors — a company of knights who gathered around the hearth in the megaron. They now fought with spears as well as swords and they used small metal shields that allowed them to move quickly on the field. They also had bronze armour – breastplates decorated with gold and plumed helmets with long nosepieces and face protectors around their jaws. Such armour was expensive and only the noblemen could afford to buy it. The noblemen were called the “Companions of the King” and it was their duty to protect the rest of his subjects. For battles were not fought by thousands of troops, but by a few noble knights who rode to war in chariots and challenged the knights of the enemy. Sometimes kingdoms were gambled on the single combat of two men, each the champion of his own people.

In their palace halls, the knights still welcomed the minstrels, the wandering poets who played on small harps and chanted their verses in return for a meal and a place to sleep. The minstrels in turn began to make up new poems about the Achaean champions. Ofcourse, they still recited the stories of the gods and the ancient warriors but now, as they journeyed from castle to castle, they added the adventures of the heroes to their poems. Other poets heard them and wrote their own verses about the knights. The stories of the Achaeans, told and re-told became the legends of Greece — tales chanted in the glow of countless hearthfires.

The Trojan War

The favourite story, the one that every minstrel was sure to know, was about the Trojan War. It was the story of Achaean heroes who sailed across the Aegean Sea to attack a powerful fortress city, Troy, the home of a band of warriors as courageous and noble as the Achaeans themselves. There were many ways to tell the tale, but it always began, as had the war itself, with the king of Mycenae. He was a king who commanded kings, the man to whom rulers turned for counsel and protection. His own city was so strong that years later, whenever the Greeks spoke of the time with the Achaeans ruled Greece, they called it the Mycenean Age. This great king’s name was Agamemnon and it was he who planned the attack on Troy. He called for all the Achaean fighting men to sail with him and they came eagerly. They gathered at the seacoast, an army of the finest knights in the Peloponnesus. As they boarded the warships, the priests made their sacrifices. They prayed first – to the old Minoan goddess, the mother of the world and then called for help of a new Greek god, Poseidon, the earthshaker and god of the sea. The ships began to move and the course was set for Troy.

When the fleet had crossed the Aegean, the Achaeans beached their boats and moved across the plain toward Troy, but there they stopped because the city walls were so tall and thick and strong that it was said they had been built by the gods. The Achaeans made their camp on the plain outside and besieged the city. Weeks passed, then months and years. The walls stood as strong as ever, with the Trojans locked in and Achaeans locked out. Knights on the plain shouted out their challenge and Trojan guards hurled down their answers from the battlements. The Achaeans would win one fight and the Trojans won the next and nothing was settled.

So it went for ten years – from about 1194 to 1184 B. C. Then suddenly, things changed. The minstrels said it was because the gods had decided in favour of the Achaeans. At last, Agamemnon’s soldiers found a way into the city. Years later, when the story was told, no one could say exactly how it had been done. Some minstrels told of spies, who slipped past the Trojan guards and opened the gates at night. Others said that the Achaeans had found a weak place in the wall and crashed through. Still others told of a huge wooden horse which the Achaeans built. The soldiers left it standing on the plain, marched off to their boats and set sail as though they were leaving Troy, but they left behind a small group of men hidden in the hollow body of the horse. To the Trojans, who were certain that the Achaeans had given up the fight, the wooden horse seemed a token of peace or perhaps an offering to the gods. They hauled it into the city as a victory prize. Late at night, when the guards were asleep or busy celebrating, the Achaean army had returned in the darkness and was waiting just outside.

Agamemnon’s soldiers poured into Troy. They ran through the narrow streets, slashing at the Trojans with their battle-axes. They dragged the Trojan king and his archers off the wall, then tore down the war itself and set fire to the houses. The Trojans were killed or ran away. When the city was in ruins, the victorious Achaeans gave thanks to the gods for their triumph and then sailed for home.

So went the story and much of it seems to have been true. There was actually a great fortress-city called Troy and its people were well prepared for battle. They had been prepared, for their city stood in the eastern bank of the Hellespont, the narrow channel that lead from the Aegean to the Black Sea.beyond the channels lay the lands of strange tribes whose towns were rich and whose people were eager for trade, but the king who ruled Troy also ruled the channel. He alone decided which ships would sail through it and which had to turn back. Merchants wishing to trade in the Black Sea had to come to terms with the Trojan king first and usually it was expensive. Many kings envied Troy’s power over the Hellespont. Others simply wanted free passage through the channel. Some of them, like the Achaean kings, were willing to fight for it.

The ancestors of the Trojans themselves come to Troy as invaders. They had built their stronghold on the ruins of the one they had destroyed and below that lay the ruins of four even earlier Troys. When an earthquake knocked down the new city, the Trojans had had to build again – the seventh city on the pile. Its palace was tall and handsome, but its streets were narrow and the houses were small, roughly made and crowded together. All of the architects’ skill and the efforts of the workmen had gone into building the walls. They were as large as the storytellers said they were – fifteen feet thick, twenty feet high and topped with towers and platforms for archers. As for houses, it was enough that they were safely inside the walls and that the storage tanks under their floors were filled with food.

With such preparations, Troy could hold off an enemy siege for weeks or months. If the Achaeans did not actually camp outside the walls for ten years, they must surely have been forced to wait for a discouragingly long time. They did find a way into the city at last, probably by breaking through the one weak spot in the wall. The section above the steepest face of the hill was slightly thinner than the rest, because no one thought that an enemy would attempt to attack from that side. The Achaeans has little time to enjoy their victory, however, for suddenly their own cities were in danger. A new mob of invaders had found the paths that led south through the mountains from Europe. They had come from the Danube country, the no man’s land northeast of the mountains and already they were fighting and plundering their way toward the Peloponnesus. Refugees fleeing to the south, told terrible stories of the strength and cruelty of the invaders, whom they called Dorians. They said that the Dorians were as fierce as the Achaeans’ own barbaric ancestors. They said that they fought with sword’s made of new metal, iron, that splintered the strongest bronze weapons.

The Achaeans prepared to defend themselves. Women and children from the country towns were brought to castle cities where they would be safe. Their husbands and brothers were sent to guard the seacoast and the Isthmus, the strip of land at the top of the Peloponnesus. The metalsmiths worked day and night, hammering out swords, axe heads and shields. The kings’ clerks scratched onto the clay tablets the records of chariots sent north, children moved south, arms heaped in the palace halls and the oil that was to pay for it all.

Then the attack came. The Dorians swept across the Peloponnesus and nothing could stop them. when they surrounded the castles, the Achaeans inside lit bonfires, the signal that would bring troops from other strongholds. The only reply was the smoke of their bonfires, more cries for help. Later, there were still greater clouds of smoke and fires that lit the plains at night. Each meant a castle captured, its people murdered and its buildings destroyed.

Mycenae was gone. Less than forty years after the time of Agamemnon, his kingdom was torn apart and his palace was a ruin. The great jars of oil made a white-hot fore when the Dorians tossed their torches into them. Timbers in the walls burst into flames and the palace collapsed. Only the tholos, the great burial chambers built into the side of the castle hill, were safe and the strange graves of the first kings had cut like wells into the rock beneath the palace. Hidden under the broken stones, they held the bodies of kings and treasures of gold, bronze and painted pottery. In the ruins above, the clerks’ like clay tablets were baked hard by the fire. In three thousand years, these things would be the proof that the legends of Agamemnon and the Achaeans were true.

The Dorians took almost all of the Peloponnesus. The Achaeans who survived were pushed into a little corner on the northwest coast. This was a time of wandering and killing, a Dark Age which began about 1000 B. C. and lasted nearly two hundred years.

As the Dorian warriors invaded other parts of the peninsula, the refugees moved on in search of land. When there was no room for them on the mainland, they set out across the Aegean Sea. From the burned-out highland cities, the tribes which called themselves the Aeolians went to Asia Minor. Other tribes called the Ionians, were forced off their lands in Argolis and attic, just northeast of the Isthmus. They, too, went to Asia Minor. Then the Dorians, not satisfied with owning the Peloponnesus, also took the two big islands of Crete and Rhodes but gradually the invasions died down. The homeless found new homes. Settled in their new lands, the Aeolians, Ionians and Dorians began to build. Little towns appeared, then cities. The Dark Age was coming to an end and the greatest age of Greece was beginning. The people of the new cities, though they belonged to rival tribes, all called themselves Greeks. They considered their cities part of the Greek world. It was a world that had spread until it now included all the lands surrounding the Aegean Sea, as well as including all the islands in it.