Across the Aegean, from the oriental court of King Darius of Persia, came messengers to all the city-states of mainland Greece. Their words were smooth, their smiles like sneers and they demanded gifts for their master – earth and water, the ancient tokens of tribute and surrender.

The Greeks in Asia Minor already knew the Persians – too well; once the smiling messengers had come to the cities. After the messengers, the soldiers came, attacking the little poleis, one by one, until all of them were taken. Nothing could stop the Persian armies. From the capital, deep in Asia, they had pushed westward and they had gone so far that the journey home was counted in months instead of miles. They had conquered Egypt and Phoenicia, the kingdom of sailors. Now Darius, their king, meant to add Greece to his empire. He would do it quietly, if the Greeks gave up without a fight. If not, he would send his soldiers and take Greece by force.

When the messengers arrived, the men of some poleis bowed their heads and gave the tokens; if Darius came, they would not fight. Others refused. The Spartans dropped the Persian ambassadors down a well and told them to find their earth and water there. At Athens, Darius’ messengers were thrown into a pit.

Darius was not sorry that the Athenians were so bold. He had a grudge to settle with them and he looked forward to seeing his troops destroy their city. Seven years before, in 499 B. C., Athens and Eretria, another city on the mainland, had sent help to the Greeks in Asia Minor. When Darius was told about it, he had sneered, “The Athenians – who are they?” He had called for his bow and arrow, which he shot toward the heavens. It was his message to the gods, asking them to let him punish Athens. Then he commanded his servant to say to him three times each day, “Sire, remember the Athenians”.

Herodotus, the historian, told the story when he wrote about the three times that the kings of Persia tried to conquer the Greeks. The luck of Athens had never met so harsh a test before. When the greatest army in the world picked Greece to be the next victim, only Sparta, out of all the city-states, was ready to defend itself.

Nature saved the Greeks from the first attack. The Persian fleet sailed close to the rocky coast, keeping watch over Darius’ army, which was moving by land. A storm blew up and smashed the ships against the shore and the expedition had to turn back. Two years later, in 490 B. C., the Persians tried again. This time they carried their soldiers on the ships and sailed straight across the Aegean to Eretria. They took the city, burned it to the ground and then crossed the narrow channel to Marathon on the coast of Attica. Athens was just a good day’s march away.

The Athenians sent their fastest runner, Pheidippides, to Sparta to ask for help. He ran as no man had run before. Not once did he stop to rest and he made the 150-mile journey in two days. When he returned to Athens, he said that the god Pan had appeared to him along the road. Pan had promised to help the Athenians if they would remember to honour him in their city. It was a good omen, but the news from Sparta was bad. The Spartan troops were willing to come, but a law of their religion said that they could not leave until the full moon had shone and that would not be for several days.

The Athenian Assembly was in an uproar when it met. Five of the city’s ten generals urged the people to vote to keep the army in the city until the Persians attacked. The other five, however, wanted to make the invaders at Marathon. Miltiades, the officer in charge of planning Athens’ campaigns, managed to make himself heard above the noise. He was in favour of the march to Marathon but, the five generals still disagreed. If the army went to Marathon and was defeated, they said, there would be no one left to defend the city. It was safer to keep the soldiers inside the walls.

Miltiades spoke again. He told the citizens that Hippias, their old tyrant, was with the Persian commanders. Were they willing to hide like cowards behind their walls, he asked, while Hippias waited for them to starve and surrender? The Athenians’ anger began to get the better of their fear. When the Assembly voted, it ordered the generals to go to Marathon to fight.

The Battle of Marathon

The plain of Marathon stretched along a curving beach edged with mountains. The Persians had made their camp between the beach, where their boats were moored and a rushing stream, which split the plain in two. The Athenians set up their camp in a little valley just above. It was a perfect position. The mountains protected the valley and no army, no matter how large, could attack it successfully. The Athenians could sit there safely for weeks and every day that passed brought the full moon and the Spartans that much closer. The Persians, on the other hand, had to move fast. Moreover, there were only two roads by which they could reach Athens. One of them was cut off by the Athenian camp. To get to the other, the Persians would have to march across the plain and the Athenians would pour out of the valley and attack the side of their columns.

For several days, the armies sat in their camps. Then the Persian commander, who had 30,000 men or more in Athens’ 10,000, decided to risk the march. As the long column moved across the plain, soldiers in the column turned and the armies met face to face, like the lines of two enormous football teams. Advancing behind their tall wicker shields, the Persians pushed the Athenian centre farther and farther back. But on the wings, the Persians were forced to retreat. The Athenian generals had deliberately left their centre weak and put all their strength at the end of the line. When the Persian wings broke and the soldiers ran for the ships, the strong Athenian wings turned and closed in. suddenly the Persians who were fighting at the centre were trapped. They scattered, dropped their arms and fled. Many were caught along the beach, for the Persian ships were already pulling away, leaving their dead and wounded behind. For a day or two, the fleet hovered off the shore of Attica. Then it turned away and sailed for home, taking Hippias back to Asia.

Meanwhile, the Athenians had lit the bonfire that signalled victory and had counted dead on the field – 192 men of Athens, 6,400 Persians. The Spartans arrived, in good time for the celebration, but too late to fight. For the men of Athens, that made it a double victory. The god Pan, who had helped the Athenians, was given a new shrine near the Acropolis. Every year, on the anniversary of the battle, a race was run to honour him and Pheidippides, the man who had run 150 miles in two days. Wherever the story was told, the contests that tested the strength of athletes in long-distance runs began to be called marathon races.

Many Greeks thought that Marathon had ended the wars with Persia. In Athens, however, there was a young politician who insisted that it was no more than a beginning. He begged the people and the generals to get ready for the battles he was sure to come. Older, more powerful statesmen disagreed with him. They said that this noisy young man, Themistocles, was just trying to make a name for himself by frightening the city. They reminded the people that Themistocles was only half Athenian – his mother came from a different polis. They said Themistocles was a show-off, always too eager to get up and talk in the Assembly, always richly dressed. That sort of thing was not Athenian, they said. If the people wanted to vote for Themistocles, they should wait until the ostracism and vote for him to leave the polis.

However, the citizens knew Themistocles as the one important man who called them by name when he met them on the street. When he was a judge, they could trust him to decide things fairly. If he was so worried about the Persians, they thought, there must be a reason for it. When the election for ostracism was held, they voted for his enemies to leave Athens. After that, Themistocles was free to go ahead with his plans for making Athens strong. He persuaded the people to spend money from the state treasury for ships – dozens of triremes, the huge battleships that were manned by three ranks of rowers. He rebuilt the old harbour at Piraeus, five miles from the city. Sparta could rely on land forces, he said, but Athens must be a sea power. His ships could defeat the Persians before they came near Attica, and in the meantime, they would help Athens to grow rich by trading.

However, Athens alone could not defend all of Greece. Themistocles was angry when he saw how little the other cities were doing to get ready for the war. He called for them to get ready for the war. He called for them to prepare defenses and to forget about their old rivalries long enough to make plans together. For years, they ignored him and did nothing. Then, when it was nearly too late, the leaders of thirty-one poleis finally met together in a Greek congress. They decided to combine their troops into one great army under the command of Leonidas, one of the kings of Sparta. The Spartans demanded control of the fleet, too, though most of the ships Athenian. Themistocles agreed and for the time being the Greeks were united, busily preparing to meet the attack.

The Persians had spent ten years getting ready for the war. King Darius was dead, but Xerxes, the new king, had sworn to avenge the defeat at Marathon. Now the Persian troops and the armies of all the nations that they had conquered were waiting in Asia Minor. Squadron after squadron of warships sailed toward the Hellespont to join the Persian fleet. The sleek Phoenician battleships and the lumbering warships of Egypt were now under Xerxes’ orders.

Meanwhile, Xerxes’ generals tried to line up the armies. There were so many men that they had trouble simply counting them. Finally, they counted off 10,000 soldiers, crowded them together in a field set up a wall around them and then emptied the field. Then they marched the rest of the troops through the field, one group after another. Each time the space inside the walls was filled, they checked off another 10,000.

No one knows just how many times the space was emptied and filled again. The Greek historian Herodotus said it was one hundred and seventy times – a total of 1, 700,000 foot soldiers but when Herodotus wrote his history, nearly half a century after the war, he used the figures the old soldiers remembered. Probably they were less than half that number of foot soldiers. Even so, with cavalry, sailors, marines, officers, attendants, grooms, cooks and the rest, the force that Xerxes called together to attack Greece was the most gigantic military machine that the Mediterranean world had ever known.

Xerxes gave the order to march. Rowers pulled at their oars, the cavalrymen spurred their horses and the infantrymen marched to Hellespont and stopped. The bridges built to carry them across the water had been washed away by a storm and Xerxes bellowed with rage. He ordered his men to give the waves three hundred lashes while they shouted: “Treacherous river, Xerxes the king will cross you, with or without your permission!”

A string of boats was lashed together to make a new bridge and the armies of Xerxes walked across the Hellespont. In the lead were the Persian foot soldiers in coats of mail, with their tall bows slung across their shoulders. Behind them stretched a strange, long parade, the men of forty-six nations in the war gear of their homelands – cotton-clad Indians and Caspians in goatskins; Sarangians in elegant high boots and brilliantly coloured cloaks; Sagartians, who lassoed their enemies and finished them off with daggers; the Sacae, who fought with axes; Thracians in foxskin caps and Colchians with cowskin shields; bronze-helmeted Assyrians, with lances and short swords and Ethiopians, who wrapped themselves in the skins of leopards and lions and used arrowheads of stone. All of Asia marched against the Greeks. The war that was about to begin would be East against West and to the winner would go Greece, Aegaean, the Mediterranean and perhaps the world.

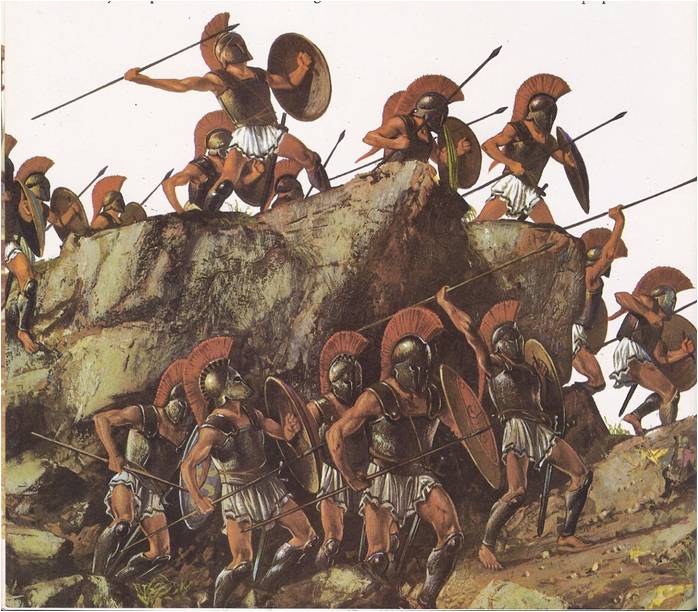

In July 480 B. C., the Persian armies, marching south through Thessaly, ran into the first strong Greek defense. The Spartan king, Leonidas and a force of 7,000 men had blocked off Thermopylae, a narrow pass fenced in by mountains and the sea. It was the one place where a small Greek army could hope to hold off Xerxes’ hordes. The ends of the pass were so narrow that only a few attackers could come through at a time and they would be easy targets for the Spartan spearmen. The only way around the pass was a steep mountain trail. The Persians probably did not know of it, but, taking no chances, Leonidas had it guarded by 1,000 men.

Meanwhile the Greek fleet had moved up to meet the Persian ships that always followed Xerxes along the coast. A lucky storm and a daring raid by an Athenian squadron delayed the Persian fleet. Now it was up to the men at Thermopylae to stop the army. Xerxes came to the west end of the pass and for four days he waited. On the fifth day, he attacked, but the Greek spears drove his men back. He tried again the next day and again he failed. Then, he found a Greek named Epialtes who was willing to show him the way through the mountains. The traitor and a troop of Persians scrambled to the top of the path and the men who had been sent to defend it dropped their arms and fled.

The Battle of Thermopylae

When Leonidas was told what had happened, he sent half of his men away to safety. He and the best of his Spartans stayed where they were, determined to hold off the Persians. In the morning, Xerxes’ troops attacked both ends of the pass. By nightfall, every Greek at Thermopylae was dead and Xerxes gave his Persians the order to march on toward Attica.

Fear swept Athens. The Spartan generals had pulled back the Greek armies to the Isthmus, the shoestring of land at the top of the Peloponnesus. The Isthmus was an easy place to defend, they said and it protected Sparta – but Athens was left defenseless. The leaders of the city hurried to Delphi to ask the Oracle for the advice of the gods. The Oracle’s reply was terrible: “All is ruined, for fire and the headlong God of War speeding in a Syrian chariot shall bring you low.”

The whole city prayed to Athena, begging her to ask Zeus for some promise of hope. The Oracle spoke again: “The wooden wall shall not fall, but will help you and your children.” The message was puzzling, but Themistocles saw its meaning. The wooden wall was a barricade of ships, he said and the Athenians must go to a place where their ships could protect them. He urged them to flee to the island of Salamis. The Greek fleet was already moored in the bay between the island and the coast of Attica and he promised that, no matter what the Spartans wanted, the ships would remain there.

The people did not want to leave Athens, but Themistocles said that he knew no other way to save them. so they gathered up the few things they could carry, took a last sad look at their homes and the temples on the Rock and boarded the boats that would take them to Salamis. Behind them, the great city fell silent, except for the dogs that ran through the streets, howling for their masters.

On September 17th, the Persians entered the city. Only the Acropolis was guarded. There a little band of soldier and priests held off the attackers, rolling stones on them from the top of the hill, but after two weeks, the Acropolis was taken and Athens was burnt.

Victory at Salamis

Now the Spartans demanded that the fleet be sent to help them defend the Isthmus but, Themistocles was determined that his wooden wall would stay just where it was. When the war council met, he asked the other commanders to vote against the Spartan plan – but they were afraid. The Bay of Salamis was not a safe place, they said. It had only two little entrances and the Persian fleet was already sitting just outside one of them. Themistocles answered that the two little entrances made the bay an ideal spot for a battle. If the Persians could be tempted into attacking, their ships would have to come into the bay one or two at a time. The Greek warships inside could easily pick them off.

While the council argued, Themistocles slipped out of the room and wrote a letter which he gave to the messenger to take secretly to Xerxes. In the letter he warned the Persian king that the Greek fleet was planning to leave the bay that night. He told Xerxes to block the entrances and to attack in the morning. He gave his promise that he and all the ships of Athens would desert the Greeks and fight for Persia.

Before evening it was reported to the Greek war council that Xerxes had blocked off the other entrance to the bay. There could be no more talk of taking the fleet to the Isthmus. Instead, Themistocles outlined his plan for defeating the Persian attack.

Xerxes too, sat in a council of war, but there were no arguments. When he ordered his admirals to sail into the bay at dawn, they looked at one another in surprise, but none of them dared to say the plan was foolhardy. Them the king told them his secret – the battle was already as good as won, for Themistocles would fight on the Persian side. Xerxes ordered his golden throne set up on a platform on the shore, so that he could have a good view of the victory. While it was still dark, he had himself rowed to the beach and climbed onto the throne. At dawn, his ships began to move silently into the bay.

Themistocles’ plan worked perfectly. The first Persian ships were sunk before they had a chance to fight. When more of them came into the bay, they jammed up until they could hardly move at all. They were easy targets for the Greeks, who nosed into them from the side, rowed hard and smashed them into the shore.

Xerxes stood up on his throne and stamped his feet in rage. He howled orders across the water, cursing Themistocles and calling his admirals fools and cowards. By the end of the day more than two hundred of his ships had been sunk, while others retreated and fled for the Hellespont. Xerxes went with them.

More than a million enemy soldiers still occupied Greece. When Themistocles sent word of his victory to Sparta, he suggested that it was a good time to begin the fighting on land. The Spartans replied that they were eager to do so, but unfortunately there had been an eclipse of the sun, a very bad omen. Winter came and the Persian troops pulled back to their main camp in Thessaly. The Spartan generals waited at the Isthmus and Themistocles tried to persuade them to do something about protecting Attica. In the spring, when the weather was good for fighting, the story was the same. By early summer, the Persians were moving south again and the Spartans, though they said they wanted to help their Athenian friends, had a religious festival which kept them at home. Meanwhile, the Persian commander had sent an ambassador to Themistocles with an offer of peace on good terms. Themistocles’ answer was short. “Tell your commander,” he said to the ambassador, “that the Athenian say: ‘So long as the sun rides through the sky, we will never come to terms with Xerxes.’” However, when he wrote to the Spartans, he pretended that he had not yet made up his mind. He told them to move, and quickly, or he would accept the Persian offer. The Spartans decided that it was possible to march their troops north.

In August, the Greek army met the Persians neat the little town of Plateau, about thirty miles from Athens. The Spartans had talked much and done little, but now that they were in battle, they lived up to their boasts. Even the Persian cavalry was no match against the superb Spartan foot soldiers. As the lines of Greeks shields and spears moved relentlessly across the field, the horses bolted and the lines of infantrymen scattered. Then the Persian commander was killed and his soldiers dropped their shields and ran.

The Asians Leave

There were no more battles. Duty and tired, their armour tarnished and their food packs almost empty, the long columns of defeated Asians began the long march back to Hellespont. They would not come again. Athenian ships and the soldiers of Sparta had saved Greece for the West.

For Themistocles, there was one more victory. When the generals and admirals went to their temples to thank the gods for helping them, they had to give special thanks for the men who had served Greece more worthily than all the others. Each of the commanders voted for himself as the most trustworthy and for Themistocles as the second most worthy. In a country where every man longs to be the best, that was honour indeed.