Far to the south of the Greek Peninsula lay the large island of Crete. It was the home of a nation of sea-warriors – cruel, dark, handsome men, who claimed the eastern Mediterranean and all the Aegean Sea as their own. For eight hundred years — from 2200 to 1400 B. C. — they made good on their claim.

The Cretan seamen strutted about the decks in loincloths and high bools. They wore clanking jewelry of finely worked gold, curled their long hair and rubbed their bodies with perfumed oil so that they glistened in the sunlight. They were fighters and they knew every trick of sailing and of piracy. With the sharp bronze prows of their warships, they smashed the sides of the ships which dared to meet them in battle.

No one could remember when they had first come to Crete. Perhaps they had once been Asians, but the island had been their home as far back as 4000 B. C. At first, they had been farmers. Then they had discovered the gold that waited at the ends of the sea lanes. They began to settle pottery and olive oil to the rich Egyptians. As they grew more daring, they were trading along the coasts of the Aegean Sea. By 1700 B. C., their sleek merchant ships were the best vessels afloat and their battleships were the strongest. By 1600 B. C., when the Greeks were cautiously trying out clumsy little boats that wobbled in the waves, the king of Crete would call the whole Aegean Sea his private empire.

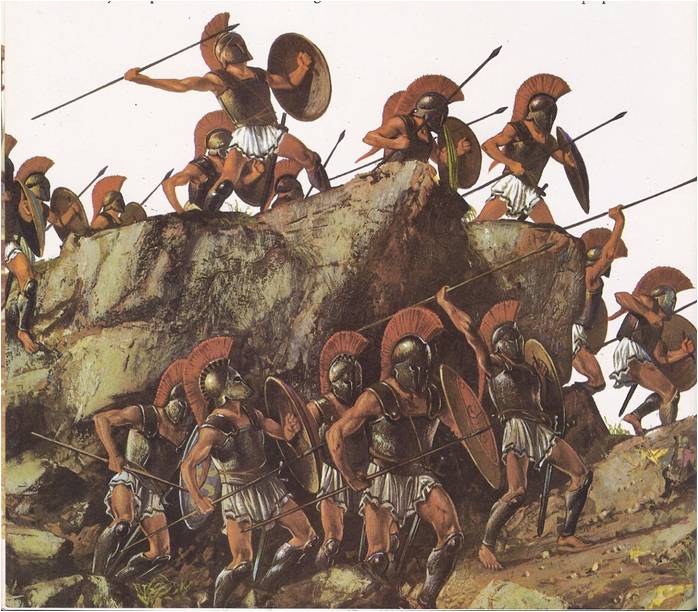

As soon as the little towns in Greece seemed wealthy enough to make good customers, the Cretan merchants came calling with things to sell – delicate pottery, brightly painted with flowers and sea creatures; leather armour with bronze plates for extra protection and jewelry of gold, silver and a rare, precious metal called tin. The Greeks were delighted with the Cretan goods and bought all they could afford. When the next trading ship appeared on the horizon, the towns-people rushed to the shore, eager to buy and to hear the news of the world beyond their shores.

The Cretans who first came as merchants often came back as bullies and robbers. They treated the Greeks scornfully and threatened them until they were given gold. Sometimes they kidnapped children and took them to Crete to serve as slaves. The little towns were too weak to do anything about it and a Cretan sail on the horizon became a signal of danger. The townsmen hid their families and waited in fear as the ship came in to land.

The Greeks never forgot the stories of horrors of Crete. Long after the Cretans had lost their power, people on the mainland still talked about the Minotaur, the monster that the king of Crete kept in is great city, Knossos. The Minotaur, they said, had the body of a man and the head of a bull. He lived on human flesh. Each year a black ship of war was sent from Knossos to Greece to collect the sacrifices for the monster. At every town, the captain demanded to see the children. He chose the seven most handsome youths and the seven prettiest girls and sailed away with them.

At Knossos, the children were sent into the Labryinth, a building with so many rooms and hallways that no one who went into it ever found his way out again. There the Minotaur waited and when his lost and frightened victims came upon him, he killed them.

The Real Minotaur

It was only a legend, ofcourse but Greek legends were full of history and the tales that seem the most fantastic often came the closest to the truth. The Minotaur was an imaginary beast, but the Cretan priests who wore masks in the shape of a bull’s head were real. The monster’s name meant “the bull of Minos,” and Minos was the name of a king of Crete, a ruler who was so famous that the Greeks began to call his people “Minoans”. This king did have a kind of labyrinth – his enormous palace at Knossos. From his throne room, hundreds of rooms and hallways and courtyards spread across five acres of land.

To a Greek, who knew only the rough fortresses of the mainland, such a place must indeed have been a labyrinth in which he could get lost and never find his way out. As he wandered through it, he would have come upon religious shrines decorated with the great double-edged axes which were the sacred sign of Crete. They were called labrys. On the palace walls, he would have seen paintings of athletes leaping around huge bulls and grasping their horns to somersault over their backs. There, perhaps, was the truth behind the story of the young Greeks who were taken away in the black ship. In Knossos they were trained to become “bull-dancers” for the entertainment of the Minoan king and his noblemen. When they were sent into the arena with one of the ferocious black bulls, they teased him until he rushed at them; then they jumped away from his sharp horns or caught at the horns and flipped themselves over his head. It was a dangerous sport and sooner or later the dancers were killed. For the stranger from Greece, wandering through the palace, the paintings of the bull-dancers were a bitter reminder of the cruelty of king Minos and of his power over the Greeks.

A lone stranger could not wander far, however, nor did he have much chance to get lost. The palace was bustling with people to show him the way and there were guards at many of the doors. The palace was the centre of a rich, busy city. From the cool veranda next to his royal chambers, King Minos looked down on rows of handsome houses. Many were two or three stories tall, with wide windows and tree-shaded terraces. No wall circled the town or the palace. Minos said that his ships were his wall; they were strong enough to frighten away or destroy any invader.

Life was comfortable in Knossos. When a man was home from a voyage, he could enjoy himself. There were feasts and processions. Dressed in glittering costumes, the people marched singing through the great, bright halls of the palace. Royal banquets were noisy affairs, with plenty of food and strong wine, followed by dancing. The gold necklaces and bracelets of the dancers caught the flickering light of the torches and jangled in time to the music.

The palace had a theatre and an arena for games like the bull-dancing, but bull-dancing was more than a sport. Sometimes a bull was killed and his blood offered as a sacrifice to the Lady of the Wild Creatures, the mother of the earth, who was the most important Minoan goddess.

There was a Minoan god, too – a young man. He may have stood for the king, a god on earth but he was not as powerful as the great goddess. Minoan women did not let their husbands forget that. They reminded the men that, in some places where the goddess was worshipped, women ran things and their husbands did as they were told. That was not true in Crete. There, men and women were equals – but the ladies insisted on their rights. They dressed themselves in fashionable long, flounced skirts and tight bodices, put up their hair and joined in the feasting at the palace just as the men did.

For three hundred years or more, there were good times as Knossos. The king ruled the Aegean and his ships came home laden with the riches of the world. Then it all changed.

The Fall of Knossos

There was another chapter in the legend of Crete, a final chapter. The storytellers said that Theseus, a young Greek prince, was brought to Knossos as a sacrifice to the Minotaur. Like so many prisoners before him, he was put into the Labyrinth but Theseus was a favourite of the gods. When he came upon the Minotaur, he did not cower or try to flee. Instead he fought the monster with his bare hands and killed him. With the death of the Minotaur, King Minos’ power was broken. His palace was destroyed, his warships were defeated in battle and Theseus, a Greek, became the ruler of Crete.

No one knows how it actually happened, but the power of Crete and its navy was broken. Knossos fell about 1400 B. C. The palace without a wall was invaded and burned, probably by Greek raiders from Peloponnesus. The Greeks had learned to build good ships and were no longer afraid to fight. Minoan ships disappeared from the sea and the Minoans themselves began to be forgotten. Crete became just another Greek Island.