In Sparta, the shops in the market place had little gold or jewelry to sell and no fine furniture at all. The people in the streets were not well dressed. Even the temples, although big, were plain and there was little in Sparta to show that this was the strongest polis in Greece.

Sparta was old fashioned and proud of it. The polis had begun as a kingdom and it stayed a kingdom. The only change its citizens made in more than 400 years was to have two kings instead of one. Each kept a watchful eye on the other and the one who was the better general took charge of the army.

For a Spartan, that was progress enough. He did not like experiments. The system that modern Athens called “democracy” looked to him like bad organization and if there was one thing a Spartan wanted it was to keep things in order. His own days and years were run on a military schedule, because he was a soldier in the army. Each citizen of the polis was in the army. He started his training when he was seven and he remained a soldier until he was sixty. His orders came from his officers, the kings and the five ephors who managed the day-to-day affairs of the city. He obeyed orders and had no time for experimenting with newfangled ideas.

In the early days, Sparta had been very much like Athens. By the seventh century B. C., when Athens was changing almost from day to day, the Spartans established their own way of doing things. As a matter of fact, they had no choice. Their ancestors, a fierce tribe of Dorian invaders, had taken the city from its old Achaean rulers. Using iron swords, they had quickly overrun the neighbouring kingdoms. By the time they stopped, they had conquered the entire southern half of the Peloponnesus. This gave them much land, as well as the serfs they needed to work on the land. However, it gave them trouble, too, because there were many more serfs than Spartans.

In the seventh century, the serfs, who were called helots, rose up against their masters. It took every citizen to hold off the furious mobs that attacked the clubs and sticks and broken hoes. During the long fight with the serfs, the city was turned into a military camp. The people lived in barracks and ate in public mess halls. Comforts were forgotten. There was no time for anything that did not help to win the war. When at last the helots were beaten down, the Spartans did not dare to put away their arms. They knew that at the first sign of weakness the helots would be at their throats again. So Sparta remained a city of soldiers standing watch over its serfs.

The big army, always in top fighting condition, began to worry the rulers of nearby poleis. Their own troops were not nearly that strong. Then it occurred to them that the Spartans might be willing to lend a hand when a neighbour was in trouble. The Spartans were willing, so long as the others agreed to let them decide where and how the battles would be fought. One by one, their neighbours came to terms. By the sixth century, all but two of the cities of the Peloponnesus had put their troops under Spartan command and Sparta was on call to defend half of Greece.

At home, serfs did the farm work and foreigners were the city’s only craftsmen and merchants. No one was rich, but that was a part of the Spartan plan. It was covered by their strict laws, which had been written by an ancient king named Lycurgus. No one remembered exactly who he was or where he had come from. People simply said he was a relative of the gods and let it go at that. When they talked about law, however, they were always careful to say, “Lycurgus said…”

Lycurgus had believed that rich citizens would be tempted to disobey their officers. For that reason, citizens were not allowed to go into business and they gave up their gold and silver coins for money made of iron. The new money would not buy much and a fortune in iron was useless. It took a big cupboard to hold a hundred dollars worth of iron bars and an ox cart to move them. In fact, the only handy thing about them was that they were completely safe from rubbers.

Anyway, Spartans had little use for money. Luxuries were against the law, because they made men soft. The polis furnished its citizens with necessities. Lycurgus had laid down the law on almost everything that could happen in the life of a man. At birth, an official decided if the baby looked healthy enough to be able to live. At death, another official decided how many people could go to the funeral. In between, there was the army.

At the age of seven, the boys left their homes and began training. Every lesson was meant to toughen them up. Summer and winter, they went barefoot and wore light clothes. Exercises made them strong and fast, but not until the time of the Peloponnesian Wars did Sparta allow the athletic contests that the Greeks loved. Soldiers who tried to outdo each other, Lycurgus said, became rivals instead of a team. The greatest Spartan contest was a public whipping; the winner was the boy who took the worst beating without a cry.

Evening in Sparta

When the boys came to their mess halls after a long day of marching and exercises, they found little food on the tables. Lycurgus said that thin children grew up, not out. Besides, the boys were expected to steal enough food to fill their stomachs – that was how soldiers lived in the field. Young Spartans were not punished for stealing, but for being caught at it.

In the evenings, there was music, the one Spartan art. It was alright for a boy to learn to play the flute, because the army marched into battle to the piping of flutes. The songs were rousing choruses and ballads about victorious heroes, the kind of songs that were good for cheering tired soldiers. When it was time for sleep, the boys made their beds of rushes, breaking the tough stems with their hands because there was a rule against cutting them with a knife. In cold weather, they added thistledown for a little warmth and if their beds were neither soft nor warm, they were too tired to care.

At twenty the young Spartans went into the regular army. They could marry then, but they still had to live in their barracks. They were not allowed to have their own homes until they turned thirty, the age at which they officially became men. Even then, however, they took their meals with the army; because Lycurgus said that all men should eat together, sharing the same bread and meat. Along Hyacinthian Street, in the middle of the city, stood the rows of mess tents. Each was a club for fifteen soldiers. A club picked its own members and no one was allowed to join unless all the members voted to invite him. Choosing the right men was important, because the clubs not only ate together, but fought together when the army went to war. When they were in Sparta, each man was expected to contribute a certain amount of food every month: a bushel of wheat, five pounds of cheese, two and a half pounds of figs, eight gallons of wine and a little money. The money bought meat for the famous “black broth” that kept the Spartans strong and jolted the stomachs of most other Greeks who tried to swallow it.

After the meal, the men went to their houses, finding their way along the streets without torches- that was a good practice for marching in the dark. At home, their wives and daughters would already have eaten. They had more time to themselves that the men did and they were not shut up in their houses like the Athenian women. Their tongues were free, too. It was an old joke in Greece that Spartan men were made tough by the harsh words of their women.

There was another Greek story, however, about the Spartan mother’s farewell to her son before his first battle. Other women might weep and pray for their sons to come home safe, but Spartan mothers only said, “Return with your shield or be carried dead upon it.”

Most Greeks believed that story. If they smiled at the Spartan’s rude and narrow way of life, they never laughed at his prowess in battle. His speech was short, his comforts few, but soldiering was his trade and fighting was his art. He would never bring shame to himself or to his polis by dropping his shield and running. He would stand his ground or be killed.

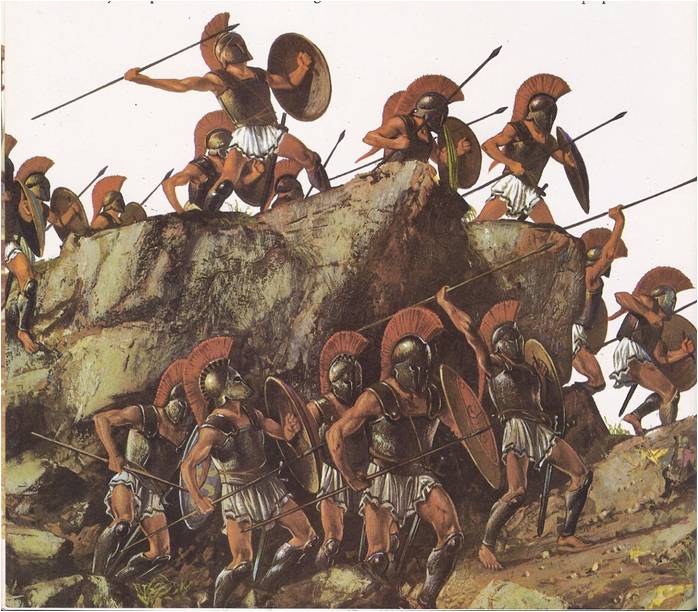

The one time that Spartans allowed themselves to be elegant was in battle. When the flutes began to play, they marched toward the field as though they were marching to a party. Their bodies were rubbed with perfumed oil. They wore their richest armour, the one expensive thing that they owned. Their long hair was curled and decked with garlands of flowers. If a man was the best soldier in the world, they thought, he ought to look it. As Lycurgus said, “A fine head of hair adds beauty to a handsome face and terror to an ugly one.”