THE story of Rome in the years after Sulla’s death was the story of a partnership of power. It was the tale of three men who bargained for the world — a rich man, a poor man and a man who was not only a hero, but looked it.

The rich man was Crassus, who had become a millionaire by setting up the only fire department in Rome. The tall buildings and narrow, crowded streets of the city made a fire a constant danger. When one house burned to the ground, the buildings on either side were likely to fall over on top of it. The cry of “Fire!” roused fear in the hearts of men whose wealth was in the buildings they owned. It was the signal, too, for Crassus and his fire-fighting slaves to come on the run. While the slaves got their equipment ready and looked for water, Crassus found the landlord of the burning building and offered to buy it from him. The price he offered was not high, but it was more than the house would be worth after it had been destroyed by fire. If the landlord refused to sell, Crassus shrugged and let the fire burn. Usually, however, the landlord sold and the firemen went to work. When the fire was out, Crassus sent a crew of carpenters to repair the damage. He soon had a building as good as new and worth a great deal more than he had paid for it. If he had talked fast enough, he also owned the buildings next door, which did not even need repairing.

Despite such dealings, Crassus was a popular man in the city. He was a good host. In politics, he took the side of the people and he greeted the poorest citizen like an old friend. He was actually eager to lend money even though he charged no interest. Of course, he expected to be paid back in time and many men — especially politicians — found themselves in debt to him. Crassus was as pleasant to them as before and simply suggested that, until they could afford to repay the loan, they might lend him their voices and votes at election time. For Crassus wanted to be something more than the richest man in Rome; he wanted to be the most powerful, as well. He dreamed of himself in glittering armour, fearlessly leading the legionaries to victory over a foreign king. Then, returning to Rome, he would put on the purple robe of a conqueror and ride in triumph through the streets. The citizens would proclaim him their hero, the consul-commander who would rule them for as long as he lived.

SPARTACUS LEADS A REVOLT

All this was in his dreams; in real life, things were different. As an officer under Sulla, he had proven his valour. He had won no fame, for Sulla did not share his glory with his lieutenants. As for the people, Crassus had won their friendship with his generosity and they were willing to forget that he had served the dictator they hated, but he had not yet proved that in him was the heroic stuff of which great commanders — and rulers — are made.

Crassus’ chance to be a hero came when Spartacus, a gladiator, led a revolt of 90,000 runaway slaves. Spartacus’ men were tough. Many of them were trained gladiators and they had nothing more to lose than the lives they risked every day in the arenas. Others were savage tribesmen who had been captured in the border wars. For two years, the army of slaves kept to the mountains, raiding and robbing the cities below. As they moved north toward the Alps and freedom, more runaways came out of hiding to join them. They slaughtered every army sent against them. Realizing how strong his forces were, Spartacus wheeled them around and began to in march toward Rome. The city, teeming with hundreds of thousands of restless slaves, had not faced such danger since the time of Hannibal. Crassus, given his first command of an army, crushed Spartacus’ main force and drove the stragglers into the lines of a second Roman army which finished them off. Crassus hurried home, expecting to be greeted as a hero. Instead, he watched while the general of the other army, Gnaeus Pompey, rode in a triumphal procession and took all the credit for breaking the rebellion.

Winning cheers as well as battles was Pompey’s special talent. With his handsome face and proud bearing, he looked as a hero should look. People said he resembled the statues of Alexander. Unlike Crassus, he had not let Sulla rob him of his fame. After his first successful campaign, in Africa, he had demanded a Triumph. When Sulla angrily refused, Pompey threatened to complain to the people and the army. “You know,” he said, staring meaningfully at Sulla, “more people kneel to the rising sun than to the setting sun.”

The aging dictator got the point and let his dashing young officer have his Triumph. Pompey tried to make it even more impressive by harnessing a pair of elephants to his chariot. The elephants could not squeeze through the city gates and he was forced to enter Rome like any other conqueror, behind four horses. He made up for that when he was asked what name he wished to be given in honor of his victory. He chose to be called Pompey the Great.

“Great in comparison to what?” Crassus said when he heard the news, but Crassus’ wealth, generosity and victories were no match for Pompey’s heroic appearance and manner. For a while, Crassus managed to keep up with his rival. After Sulla’s death, both of them had joined the people’s party and helped to destroy the new constitution which had been forced on Rome. Later, both were elected as consul-commanders and both took care to show that the Senate could not order them around. It was Pompey alone whom the citizens chose to lead a great expedition against the pirates who were robbing the Roman merchant fleet. While the senators shouted in anger, the people voted to give their favorite general a fleet of 500 ships. They put him in charge of the entire Mediterranean and all Roman land within fifty miles of its shores.

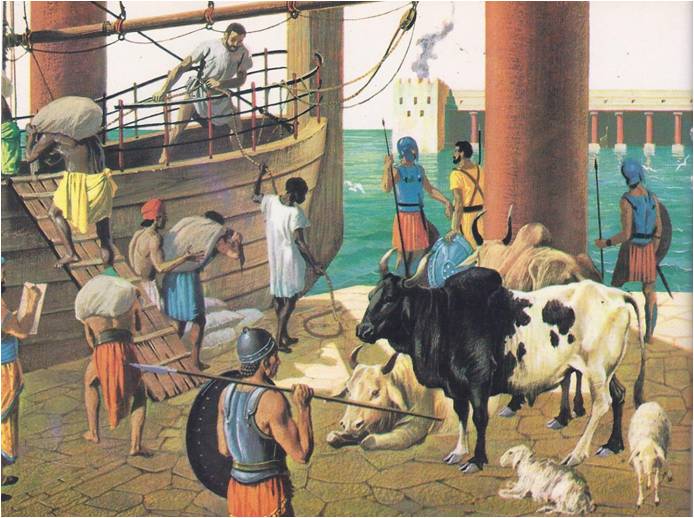

Luckily, Pompey was the right man for the job. The Mediterranean pirates were not little bands off ruffians. They sailed great fleets of stolen ships and preyed on the most important shipping routes. Their fortress-cities tucked away among the islands in the Aegean Sea, were piled high with loot. Their dungeons were crowded with prison, waiting for their families to ransom them with gold. No merchant vessel or private yacht was safe from the sea raiders and they had grown so bold that they dated to sail to the mouth of the Tiber, fifteen miles from Rome. It took Pompey only forty days to sweep them out of the Western half of the ocean. It took him only forty-nine days more to corner them in the Aegean, sink their ships and destroy their island strongholds.

THE YOUNG JULIUS CAESAR

In Rome, the delighted people outshouted the Senate again and ordered Pompey to take command of Asia Minor. There he finished off Rome’s old enemy, Mithridates. He took ]udea and conquered the last of the Seleucids, the once powerful kings who held the land that Alexander the Great had won in Asia. Then he led his legions along the Euphrates River all the way to the Caspian Sea. No one but Alexander had ever conquered so much of the Orient. When Pompey came home, he had won a huge new empire for Rome and treasure worth $36,000,000.

The triumphal procession lasted for two full days and even Crassus admitted that Pompey deserved it. It was Pompey’s third Triumph. The first had been for his conquests in Africa, the second for his conquests in Italy and Gaul and now this one for his conquests in Asia. Taken together, they added up to most of the known world, all of it conquered for Rome by Pompey. Yet he did not try to be another Sulla. He disbanded his armies and all that he asked the Romans was their agreement to the treaties he had made in the East and farmland for his soldiers. For two years the Senate ignored his requests. The senators had not forgiven the insult of the election which had given him his power. Pompey the Great was not their man and they were pleased to humble him.

Then another, younger officer, a leader of the people’s party, offered his help to Pompey. He was Julius Caesar and he came to Pompey with the idea for a partnership to rule Rome and the world. Young Caesar was a brilliant soldier and even more eager to get ahead than Pompey or Crassus. It was said that when he first read about Alexander the Great, he cried. At his age Alexander had conquered so many nations, while he himself had done nothing worth remembering. Alexander had not had Sulla as an enemy. Caesar was a nephew of Marius and Sulla had kept a watchful eye on him. Although Caesar was then only a boy, his friends had had to talk fast to persuade Sulla not to kill him. Sulla had finally agreed, but he was certain he was making a mistake. “In that youngster,” he said, “we have another Marius.”

Sulla was wrong, for Caesar was not another Marius. He had none of his uncle’s tough, peasant strength and he had to train himself to stand up to the strain of battle. Sulla was right when he said the boy was dangerous. Like Marius, he dreamed of commanding the legions and he was much more clever than Marius had been. On the island of Rhodes, where he went to stay out of Sulla’s way, he began to study at the school of Apollonius, a master in the Greek art of speech making. He learned the many ways to persuade a crowd, how to judge an opponent’s weaknesses at a glance-all the tricks of city politics which had so baffled Marius. There was no professor who could teach Caesar all he wanted to know. He taught himself, driving himself to read and think, just as he drove his body to make it strong. His textbooks were the speeches and histories of the great rulers of the world. It was not what they had done that interested him. He wanted to find out how they had managed to do it. How had they run their campaigns? How had they handled their soldiers? What did they say to the citizens they served, and the ones they conquered? As Caesar poured over his books, he learned to plan everything he did with the care and caution of a general preparing for a battle.

When Sulla died and the leaders of the people’s party dared to show their faces in Rome again, Caesar went home. Now his family connection with Marius was an advantage. It made him something of a hero to the common citizens — at least, most of them knew his name. Caesar was determined that before long they would know more about him than that.

Like Crassus, he set out to become the people’s friend. With his charming manner and skill in making speeches, it was an easy job. Just as easily, he befriended Crassus himself. The millionaire was as worried as ever that the people would not like him enough. He was delighted to have the popular young nephew of Marius as his friend. As for Caesar, he had a plan of his own.

THE FIRST TRIUMVIRATE

In 68 B.C., Caesar won a post with the army in Spain and soon the word spread that he was a daring officer, a man who deserved something better. When he returned to Rome, important men in the people’s party began to say that he ought to run for office. Of course, that was just what he meant to do. He was poor and winning the support of the Romans cost money. When he was elected Aedile, the officer in charge of public celebrations, he treated the people to the most lavish shows they had ever seen. He staged great processions, gave public feasts and once filled an arena with 320 pairs of gladiators. He became more popular than any other politician in the city, but he went far into debt. Crassus paid the bills — which had been Caesar’s plan all along. It was money well spent, because Caesar soon won offices that brought him the riches to repay the loans. His popularity was as useful to Crassus as Crassus’ money had been to him.

It was in 62 B.C. that Pompey the Great came home to two days of triumph and two years of snubs from the Senate. The conqueror of the world fumed while the senators, still trying to be the only rulers of Rome, ignored his requests. Then Caesar came up with a new plan. He discussed it first with Crassus, who was doubtful but did not say no. He talked to Pompey, who was interested if Crassus would agree. Caesar brought the two rivals together, trying to work out the details of a three-way partnership. That was a plan — a practical, Roman sort of plan, like his old arrangement with Crassus. Each of them wanted something, Caesar said. He himself wanted to be elected consul. Crassus hoped to see laws passed that would help his business friends, the knights. Pompey, of course, was worried about his treaties and the land for his soldiers. Each of them had something valuable to bring to the partnership. Caesar mentioned his own popularity. Crassus had money and Pompey — Caesar smiled — Pompey was a hero. If Crassus and Pompey could forget their old rivalry, Caesar said, the partnership would be unbeatable.

Never had Caesar tried so hard to put Apollonius’ arts of persuasion to work. As he spoke, Pompey began to see the end of his troubles with the Senate and Crassus dreamed again of his great victory. Caesar’s plan was too good to refuse. Pompey and Crassus agreed to end their rivalry and swore eternal friendship to each other and to Caesar. The three shared a bowl of wine and drank to the success of the partnership. T o seal the bargain, Caesar gave his young daughter in marriage to Pompey.

After that, it made little difference what the Senate did. Rome’s future was no longer being settled in the Senate It was settled, secretly and unofficially, by the three men who gathered around the table in Crassus’ dining room. In history, these three — Caesar, Pompey, and Crassus — would be known as the First Triumvirate. Their enemies called it the Three-headed Monster.

CAESAR’S WARS IN GAUL

In 59 B.C., Caesar was elected consul. Once he was in office, Pompey’s treaties were made official, his soldiers were awarded their land and Crassus’ laws were passed. So far, the practical arrangement was working well. Then, the next year, Caesar was given a five-year command of the armies in Gaul. It was his chance to prove his brilliance as a commander and he did. He crushed the fierce Gauls, pushing his armies, across their lands as far as the English Channel and the Rhine River. After that, he crossed the channel and took almost half of Britain. The reports that came back from the front praised Caesar’s strategy and the loyalty of his soldiers. They told of a commander who seemed never to sleep, who kept two secretaries busy at once taking down his orders for his captains. When a great revolt of the Gauls nearly destroyed his armies, he somehow held on and finally defeated the Gallic warriors.

Meanwhile, Pompey and Crassus sat impatiently in Rome. Not only were they still jealous of each other, they were now jealous of Caesar, too. The practical partnership was becoming a three-way rivalry. The senators, quick to take advantage of this, began to treat Pompey in a surprisingly friendly way. They hoped to win him to their side and break up the partnership.

Caesar called for a conference. The partners met and a new bargain was struck, one that gave each of them a command. They divided the world among themselves, like greedy schoolboys splitting up a pie. Gaul went to Caesar, Spain to Pompey and Syria to Crassus. Again like greedy boys, each began to wonder if his slice, was as good or as big as the others and each made his own, secret plan to take more than his fair share. While Pompey lingered in Rome, Caesar hurried back to Europe, where half a continent waited for anyone strong enough to take it away from the barbarians. Crassus put on his golden armour, collected an army of seven legions and sailed to the East to be a hero at last. Pompey, however, delayed taking up his command in Spain. He remained in Rome, where he could strengthen his political position.

During the next three years, everything seemed to go wrong for the partnership. Crassus’ expedition was plagued with problems. First there was the desert, a vast, hostile wasteland, where his army’s scouts lost their bearings and the legions struggled on with never enough food or water. Then there was the enemy-a host of ruthless barbarians, old hands at desert warfare and burning with hate for the Romans who had killed their champion, Mithridates. Then there was Crassus himself.

His soldiers quickly realized that he was a bungler, a general who would waste their lives. They followed him because they had no choice. They shambled along, grumbling, halfhearted, not knowing, or caring where they were going and expecting the worst. In 53 B.C.‚ in the fiery heat of the Syrian summer, the worst happened. A horde of Asian lancers and mounted archers galloped out of the desert. While Crassus looked on in horror, the Asians surrounded his troops and savagely chopped them down. Twenty thousand of his men were killed, and 10,000 were taken prisoner. Crassus himself came out of the battle alive. Afterwards, when he went to what he thought would be a truce conference, the barbarians murdered him. They stripped the splendid armour from his body and cut off his head as a prize for their king — a nightmare ending to the dreams of the richest man in Rome.

THE STRUGGLE FOR POWER

Now there were only two partners to divide the world between them. Caesar and his veterans were still in Europe. Pompey was still in Rome. He never went to Spain; there were more important campaigns to be waged in the capital. The city was in turmoil. The Senate, as always, claimed the right to run the Republic, but outside the Senate house, the streets were ruled by gangs of thugs. One gang, led by Clodius, a renegade officer, looked out for Caesar’s interests in Rome. Another, Milo’s gang, worked for Pompey. They used their fists to win votes and their swords to silence speakers who took the wrong side in an argument. When Milo’s men murdered Clodius, gang wars broke out. The senators asked Pompey to round up the toughs with his troops. They suggested that the job of keeping the peace might be easier if Rome had only one consul instead of the usual two. The one, of course, would be Pompey — if he cooperated with the Senate.

It was a tempting offer, the whole pie instead of half. It would mean betraying Caesar and breaking the partnership. After all, Crassus was dead. Pompey’s wife had died, too, and his friendship for her father had died with her. Why shouldn’t he be the only consul in Rome? For the hero who had conquered the world and resembled Alexander, it was only right. Or so the senators said and Pompey, who was never a man to underrate himself, agreed. So Pompey became the Senate’s man and its defender against Caesar. Now the political battle between the people’s party and the aristocrats was a contest between two generals, a dispute that could only be settled on the battlefield.

Caesar, sure of the loyalty of his veterans, continued campaigning. The book he wrote about his wars and victories in Gaul made certain that the Romans knew just how much he was doing for them. Meanwhile, Pompey happily took on the job of ruling Rome, and tried to win the people’s thanks in his own way. He put bigger, wilder shows in the arenas. He built a new theater, the first stone theater in the city. He opened a splendid public garden inside a square of fine new buildings. On one side of the square, he built a meeting-hall, the Curia, where he and the Senate could discuss the business of Rome in comfort. A feature of the new ball was a statue of Pompey the Great, bigger than life and looking very much like Alexander.

In 49 B.C., the former partners, now enemies, faced each other again. Caesar had been given his command in Gaul for five years and the time was up. The Senate ordered him to come home — without his soldiers. Caesar replied with an offer to disband his army if Pompey would do the same. While he waited for an answer, he marched his army to the Rubicon, the river that marked the boundary between Gaul and Italy. On his side of the river, Caesar was the consul-commander of Gaul, with the right to have an army. On the other side, in Italy, he had no lawful powers at all; he was just another Roman citizen. If he crossed the Rubicon at the head of an army, the law would say that he was an invader, an enemy of the Republic, the Senate and Pompey.

Speeding from Rome came the messengers, among them Caesar’s lieutenant, Mark Antony. Caesar’s offer had been refused, he said. The Senate commanded him to disband his legions or be declared a public enemy. Caesar nodded grimly. Then he signaled to his captains and led the army across the river. When he reached Rome, Pompey and most of the senators were gone. They had no army to equal Caesar’s and they had lied to Greece. Caesar moved swiftly. He stayed in the city only long enough for the people to elect him consul-commander. Then, as the legal leader of the Roman armies, no longer an invader or an outlaw, he took his troops to Spain and defeated Pompey’s allies there.

THE END OF POMPEY

Meanwhile, Pompey raised an army and prepared to invade Italy. Before he could sail, Caesar rushed to Greece to stop him. At Pharsalus in Thessaly, the old partners met on the battlefield. Pompey had nine Roman legions and a great force of Greek and Macedonian horsemen, the best cavalrymen in the world. Caesar had his veteran infantrymen, a few battalions of men Mark Antony had rounded up in Italy and no cavalry at all. Pompey attacked. His horsemen charged across the plain, crashing against a wall of Caesar’s footsoldiers. The tough infantrymen, veterans of countless fights against the barbarians, held their ground. They hauled at the horses, pulling them around so that they could attack the riders. By afternoon, they had killed or wounded so many men that the armies were now evenly matched. They began to push across the plain. Pompey’s legions fell back, broke their lines and ran for their lives. Still the infantry pushed ahead, to the edge of the plain, and beyond to the enemy camp.

After the battle, Pompey the Great walked from the field in silence. He spoke only once, when he saw Caesar’s soldiers trailing his men to their tents. “In the very camp?” he cried and was silent again. He escaped to a ship, sailed across the Mediterranean and anchored just off the coast of Egypt. He sent a message to the young King Ptolemy, begging for a place of refuge in his court. Then he waited while the king made up his mind. When, finally, an ordinary rowboat was sent to pick him up, Pompey knew that Ptolemy did not intend to welcome him with honour. He boarded the boat and on the way to the shore, he studied a little speech he had written in Greek, his humble greeting to his new protector. Near the beach, his servant leaped out of the beat to help him ashore. As Pompey began to stand up, one of the Egyptian sailors stabbed him from behind — the king had decided that he would be a dangerous guest. The sailors hauled him out of the boat, cut off his head as proof to the king that he was dead and left his body on the beach. Later, when the Egyptians had gone away, Pompey’s servant found a battered fishing boat half buried in the sand and he used it to make a funeral pyre for his master. It was a lonely end for a hero who had always had a crowd to cheer him.

So, of the three partners, only Caesar was left. In the spring of 48 B.C., the Roman world belonged to him. By autumn of the same year, he had almost lost it, along with his life. The trouble came when he went to Egypt looking for Pompey, not knowing that Pompey was already dead. He found himself caught in the middle of a royal family quarrel. Ptolemy, the thirteen-year old king of Egypt, shared his throne with his sister, Cleopatra, who was twenty. Sharing the throne in this way was an Egyptian custom, not something that either of them wanted. They were clever but spoiled children and jealous of each other. They constantly bickered and threw the court into an uproar with their tantrums. Then they began to plot against each other, until their feuding became the talk of Alexandria. The People took the side of the little king. When Cleopatra showed her temper once too often, a group of citizens escorted her out of the city and told her not to come back. This happened just at the time that Caesar arrived in Egypt.

CAESAR AND CLEOPATRA

Cleopatra had heard about Julius Caesar and she knew that he was the most powerful man in Rome. She arranged to meet him and found that he was a pleasant man. He was not as young as he might have been, perhaps, but he was courtly and polite. Of course, he was a very great general.

Cleopatra said she was helpless to defend herself. She needed someone strong to look after her-someone like Caesar. She was a beautiful woman and knew how to handle men. Caesar was charmed and then conquered completely. He promised to do what he could. He marched into Alexandria, captured the palace, made Ptolemy his prisoner and handed over the throne to the beautiful queen.

The Alexandrians were not pleased. They called out the army of Egypt and attacked the palace. This was more than Caesar had bargained for; he had come to Egypt with very few soldiers. For six months, it was all he could do to hold the palace. In the spring of 47 B.C.‚ he let Ptolemy go free, hoping that the Alexandrians would call off their troops. Instead, they rallied around the young king, attacking Caesar and Cleopatra more fiercely than ever. The conqueror of Pompey and the Gauls stood a good chance of being killed in this little Egyptian squabble. Then, just in time, reinforcements galloped in from Asia Minor and saved him. With their help, Caesar took control of Alexandria, killed Ptolemy and chased the Egyptian army around the desert until he was certain that no one would try to steal Cleopatra’s throne again.

By then, it was autumn, and Caesar had stayed in Egypt much longer than he had planned. He learned that the barbarians who had defeated Crassus were invading Rome’s provinces in Asia and Pompey’s sons had taken Africa for the Senate. Yet whenever Caesar thought of leaving Cleopatra, he found some reason to stay and he remained in Egypt throughout the winter.

TRIUMPH AND DEATH

When spring came and good campaigning weather, he at last said good-bye to Egypt and its queen. He formed his legions and marched into Asia to try to repair the damage which Crassus had done. He wasted no time about it. By September he had fought and won forty-seven battles and was on the way to Africa. The fighting was rougher there, the victories came slowly, but in the summer of 46 B.C., he destroyed the last of the senators’ armies. Then he returned to Rome.

His parade of triumph was as splendid as any the old city had ever seen. It marked not one but four great conquests — his victories over Gaul, Africa, Egypt and Asia. On one of the chariots that led the long procession, three words were painted: Veni, vidi, vici –“I came, I saw, I conquered.” That was the message Caesar had sent to Rome after his campaign in Asia. Now, as the chariot rolled along the street, people shouted, “Veni, vidi, vici’!” The throngs took up the shout until it echoed across the city. When Caesar himself rode by, dressed in his purple robe and carrying the laurel branch of victory, the thunderous shouting seemed to shake the hills of Rome. Veni, vidi, vici! The conqueror of the world, the champion of the people, had come home at last.

Caesar had great plans for Rome –plans for roads, plans for buildings, plans for colonies, plans for new campaigns. He would make certain that his soldiers had a fair share of the land they had fought for and that the poor of the city had food. He would send honest governors to the provinces. He himself would govern with justice, not murder. He did everything he could to show Romans that he was not like Sulla or Marius. Instead of killing the men who had worked against him, he pardoned them. He declared himself dictator of Rome for life, with the consent of the Senate and the people. It was true that no one dared to vote against this. But twice, when the mob offered him the crown of a king, he refused it. He was satisfied to be dictator; he would not destroy the Republic by becoming king.

Many of the senators came over to Caesar‘s side. Others, however, did not trust him. Caesar was hungry for power, they said. Already he had made himself dictator. If a crown was offered to him a third time, they asked, would he refuse it again?

The most determined of Caesar’s enemies in the Senate was Gaius Cassius, who hoped to stir up a plot against him. Cassius was an old officer of Pompey’s and spiteful as well; few men were willing to follow him. A very different sort of person was Senator Marcus Junius Brutus. He came from one of the oldest, most respected families in Rome. He was Caesar’s friend and he had served with him in the great campaigns in Asia. Everyone knew Brutus as a thoughtful, honest man. When Cassius came to him with his whining complaints about Caesar, Brutus at first refused to listen. Cassius came again with new arguments. He said that all of Rome remembered Brutus’ ancestors, because they had led the fight to drive the old Etruscan kings from Rome. Brutus nodded. Driving out the tyrants was the proudest event in the long history of his family. “And now,” Cassius said, “will Brutus stand by, doing nothing while a new tyrant robs the Romans of their freedom?”

Brutus made no answer, but Cassius knew that he had won his point. He gave Brutus time to weigh his love for his friend Caesar against the freedom of Rome and family duty. As he expected, Brutus at last agreed to join the plot. After that, persuading the others was easy. Men who had been suspicious of Cassius were willing to follow honest Brutus. Soon, more than twenty senators had joined the conspiracy and sworn to stop the power-hungry Caesar before it was too late.

On the morning of March 15, 44 B.C., Caesar was getting ready to attend a meeting of the Senate when his wife Calpurnia rushed into the room. Her hair was flying and uncombed and tears ran down her face. She had had a terrible dream, she said. All through the night she had dreamed of death and of danger to Caesar. She begged him to stay home and not go to the Senate. Caesar laughed and shook his head. The dictator of Rome, the commander-in-chief of the armies, could not give up important state business because his wife had had a nightmare.

Calpurnia begged him again. She said she knew that it was more than a nightmare; it was a sign from the gods. She reminded Caesar that a soothsayer had warned him to beware of this day, the fifteenth, which was called the Ides of March. When Caesar saw how terrified his wife was, he asked his priests to sacrifice an animal and study it for omens. A favorable report from the priests would calm Calpurnia’s fears and, in fact, Caesar himself wanted to be told that all was well. The report was far from comforting. The omens were had, the priests said, very bad indeed.

Like every Roman, Caesar knew that it was dangerous to ignore that sort of warning. When his friend Mark Antony came to walk with him to the Senate, he told him to go on alone and to dismiss the meeting. Another friend, a senator, urged Caesar not to insult the Senate so, especially on a day when they were going to discuss making him a king over the provinces. Once more, Caesar changed his mind. He would go to the Senate. When Calpurnia shrieked and the priests began to chatter at him, he silenced them with one sentence: “The omens,” he said, “shall be what Caesar makes them be.”

As he walked through the city, nothing seemed different or out of the ordinary. The streets were busy, as usual. The same crowds gave him the same cheers. Once a man darted out, thrust a note into Caesar’s hand, and disappeared into the throng as though he did not want to be seen. Caesar started to look at the note, but someone spoke to him and he forgot about it. Near the Senate, the Curia which Pompey had built, he heard a man call out to him. It was the soothsayer and Caesar smiled when he saw him. “The Ides of March are come,” he said.

“Yes,” the soothsayer answered, “but they are not past.”

Caesar smiled again and started up the steps of the Curia. Inside, a group of senators was waiting to speak to him. One of them walked up to him and asked a question. As Caesar turned to answer, the man pulled a dagger from the folds of his toga and stabbed him. Then the other senators in the group — Cassius and Brutus and the rest — crowded around him. Each of them had a dagger. Caesar glared at them, his eyes going from face to face, until he recognized Brutus, who had been his friend. “Et tu, Brute?” he cried. “You too, Brutus?” Then he covered his eyes with his toga and let the daggers strike. When the assassins drew back, he crumpled to the floor, just at the foot of the tall statue of Pompey.

Caesar, the last of the three partners, was dead.