MARCUS TULLIUS CICERO, a young statesman known for his dramatic speeches, stood before a panel of judges in a courtroom in Rome. He stared at them angrily. For fifty days he had travelled through Sicily, collecting facts about the crimes committed by Caius Verres, the man who was on trial. Now the judges had told him that there would not be time to listen to his evidence.

Cicero knew that the judges had been bribed. For it was no ordinary criminal that he meant to send to prison or to death. Caius Verres was an aristocrat and a senator and had served for three years as the governor of the province of Sicily. Verres’ lawyer was Hortensius, the leader of the aristocrats. Indeed, every rich or important man in Rome seemed to be supporting Verres, but Cicero was determined that this man should not escape judgment. He turned to Hortensius and offered to present his case in one day. “Would the court have time enough for that?” ‘ he asked sarcastically.

Hortensius was surprised, but he smiled and told Cicero to try it if he liked. The judges agreed.

For a moment there was silence in the courtroom, as Cicero turned to face the benches where the long lines of judges sat. Sternly he looked from man to man until he was certain all their eyes were on him. Then he began to speak. He listed Verres’ crimes: When he was governor and the commander of Rome’s army in Sicily, he had taken for himself the money raised to pay the troops. When he was governor and responsible for order and justice in the province, he had taken more money to allow pirates to rob the ports, to set criminals free and to condemn innocent men. For gold, he had tortured and killed Roman citizens who had the right to trial in Rome. When he was tax collector as well as governor, he had taxed the great Sicilian grain farmers until they starved. He had robbed the cities of their monuments, plundered their temples for gold and stolen their Greek statues to decorate his own gardens in Italy. These things, Cicero said, were as well known in Rome as in Sicily. Caius Verres had boasted about them himself.

The court was silent. What Cicero said was true, and it was true of other governors as well. Verres was only among the worst of them.

Once more Cicero’s voice rang out. Was it also true, he asked, that in Rome a rich man, whatever his guilt, could never be sent to prison for his crimes? Then Roman justice, not Verres, was on trial. Glaring at the judges now, Cicero asked them one last question. Did they dare to let Verres go free and so prove to the world that greed had destroyed the honor of Rome?

When Cicero sat down, the judges’ faces were solemn. Hortensius’ smile was gone and he made no answer to Cicero’s speech. Cicero had won his case. When Verres heard how things had gone in court, he packed his gold and the best of his stolen statues, and fled from Italy.

The year of the trial was 70 B. C., sixty years after Rome had made itself the ruling power of the Mediterranean. The Romans were learning the lessons that Pericles’ Athenians and the heirs of Alexander the Great had learned: winning an empire is difficult, but governing it wisely is more difficult still.

The conquered provinces looked to Rome for order and protection. Instead, they got governors who were out to make their fortunes and tax collectors who took money for themselves instead of for the government. Meanwhile, barbarians crashed across the frontiers. Closer to home, the Italian cities, Rome’s first allies, grew more and more angry at giving their sons to be soldiers but never being allowed to vote. There were important jobs to be done, but the Republic — Rome’s government of senators and commoners — was not doing them.

RICHES AND SLAVES

In the years when Rome was growing up, the Republic had weathered the storms of invasions and disasters. Time and again it produced men who saved the city and turned defeat into victory. Now, in the new, bigger world which Rome had conquered, the old system did not seem to work.

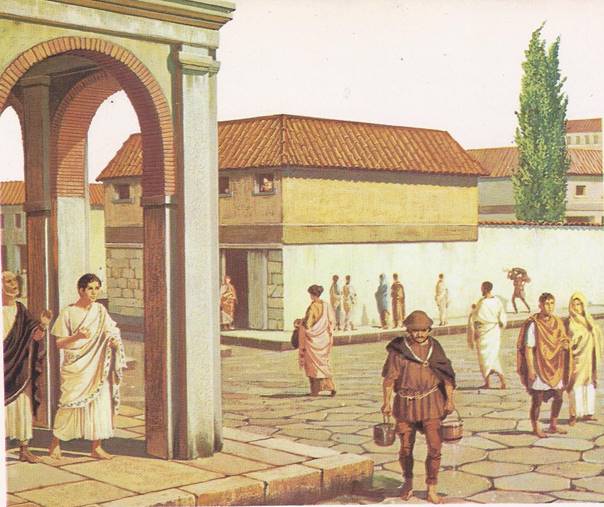

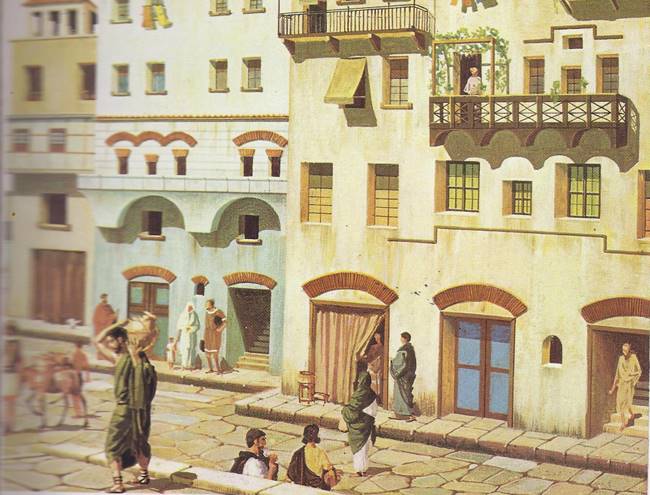

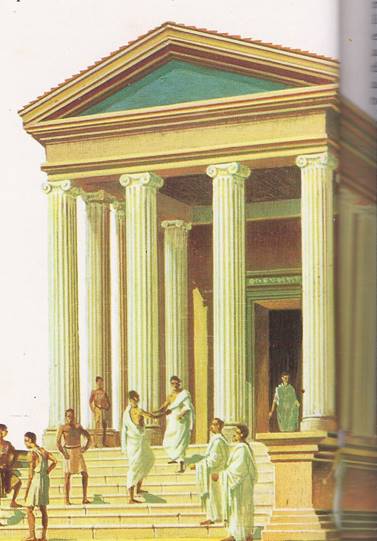

The city itself had changed. The simple houses of the old days were gone. The rich families of Rome now lived in big homes with many rooms and colonnaded courts, like the ones in Greece. Businessmen and politicians who had made fortunes in the provinces built palaces for themselves when they came home to Rome. They filled them with elegant imported furniture, decorated them with statues “borrowed” from temples in Greece, and bought dozens of slaves to do the household work.

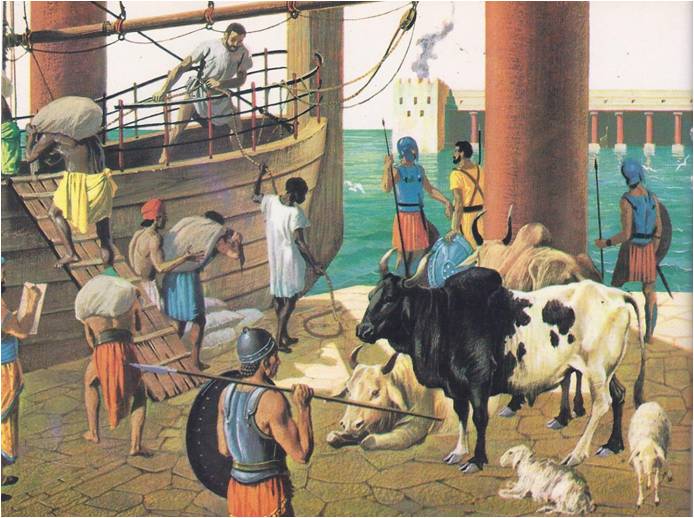

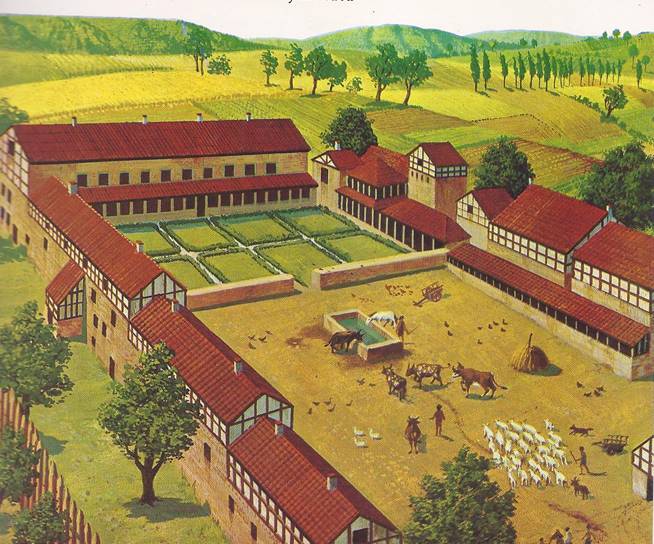

The Romans had owned slaves almost from the first. Every farmer or craftsman had one or two to help out with his work. The wars in Italy and the Mediterranean flooded the slave markets with captives: soldiers taken in battle, men, women, and children from conquered cities. The war with Carthage brought more than 200,000 prisoners to Italy. The campaigns in the East brought almost half a million more. And in the rare times of peace, the supply of slaves was kept up by pirates, who raided little coastal towns and kidnapped their people. Capua, where half the shopkeepers in Rome bought their pottery and iron, became a great center for slave trading. Prices were low, well-to-do Romans and farmers from all over the peninsula rushed to buy. A man whose father had been quite comfortable with two or three slaves to serve him now felt that he could not run his home without twenty or thirty. If he had an estate in the country as well as a house in town, he needed as many as three hundred.

When a man was sold as a slave, the kind of life he could expect depended on his skills and the temper of his master. The master was a matter of luck; one owner might whip his slaves and work them to death, while another would treat them with some kindness. But skills were a matter of education and they made a great difference. The unskilled men and women who worked on farms or spent their days in the dark tunnels of the mines knew nothing but suffering. They slept in filthy huts, had only enough food to keep them working and were often kept in chains. When they grow old or fell sick, no one did much about it. It was cheaper to let them die and buy young healthy replacements.

For a town slave, one who had talents or education, things could be very different. If he could cook well or curl his mistress’ hair, talk philosophy or teach his master’s children to read, he was a valuable possession and worth taking care of. Wealthy Romans were proud of showing off the skills of their best slaves — the scribes who copied their letters in an elegant hand, the singers who entertained their guests after dinner. A household of fine slaves gave a man standing. He saw to it that they were well fed and properly dressed so that no one would say that he was too poor to look after them.

A slave with a good head for business could earn more than food and clothes. His master might put him in charge of a little shop in the market. A portion of the profit was his to keep and when he had saved enough money he could buy his freedom. Other slaves were given their freedom on the death of masters whom they had served well.

Most of these new “freedmen” stayed in Rome. They went into business for themselves as shopkeepers, craftsmen, or clerks. Some set up as doctors or teachers and a few became millionaires. They added to the crowds in the booming foreign districts of the city, which now had nearly three quarters of a million people.

Riches, slaves, and foreigners– they were changing Rome and every change meant new trouble for the old Republic. The Romans themselves were changing most of all. Men from the oldest, most respectable families had taken to wearing soft, rich clothes instead of homemade togas. They stuffed themselves at banquets and clattered about the city in smart, new carriages. In summer, when Rome turned hot and dusty, they hurried off to Neapolis where their yachts were moored. They spent fortunes on jewelry for their wives, and bought Greek slaves to teach their children.

GREEK INFLUENCE GROWS

Rome was becoming very Greek. It showed in the statues and new houses. It showed, too, in the speeches in the senate and the law courts, for the plain-speaking Romans had become fascinated by the way the Greeks could talk. In war, a Roman knew what he was doing, but in battles of words, a clever Greek could turn his arguments inside out making him look like a fool. The Romans soon saw how useful this could be in politics and business and they wanted to learn how to do it themselves. When a pater familias planned the education of his sons, he usually saw to it that they learned Greek literature and rhetoric, the art of fine speech. Then he shipped them off to college in Athens.

Schools run by free Greeks sprang up all over Rome to teach the People who did not have the money or time to go to Greece. The ability to speak the Greek language, as well as to argue in the Greek fashion, became the sign of a man of intelligence and importance. Old-fashioned Romans objected to this “Greekness,” and the softness and luxury that came with foreign ways. Old Cato, who had called so long and so often for the destruction of Carthage, had seen a new danger. “The truth,” he said to anyone who would listen, “is that our possessions have captured us, and not that we have captured them!”

The Senate passed laws to limit the amount of gold jewelry a woman could wear and the number of guests her husband could invite to a banquet. Greek philosophers were outlawed in the city. The new ways had come to Rome to stay. Cato himself finally learned to speak Greek, the philosophers returned, and the laws on jewelry and guests were forgotten. The Romans who could afford it went on enjoying themselves.

Not everyone, however, could afford it. The streets of Rome were full of penniless men, homeless and angry. They were drifters, discharged soldiers and peasants whose small farms had gone to ruin while they served in the army. The slaves they had helped to capture made it possible for one rich farmer to run a great plantation without hired hands. The latifundia, the new, big farms, were made up of many little farms and land rented from the government. There was no place on them for the peasants, the men who had once been the backbone of Rome and the strength of its legions. The peasants left the country and came into the city. They could find no work there, either. They discovered that in a Republic ruled by votes there was still power in numbers. The poor of the city became an unruly mob, shouting for attention. Living on hand-outs from the government or from rich politicians, selling their votes in the assembly to the men who gave them the most. Without jobs, they had nothing to do with their time except wander the streets and make trouble. So the politicians began to give them free shows as well as free food.

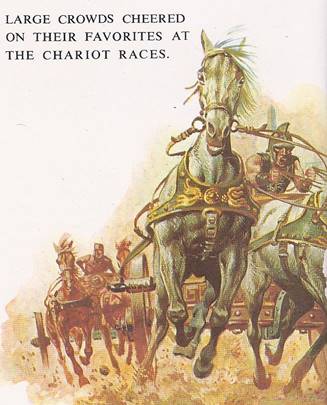

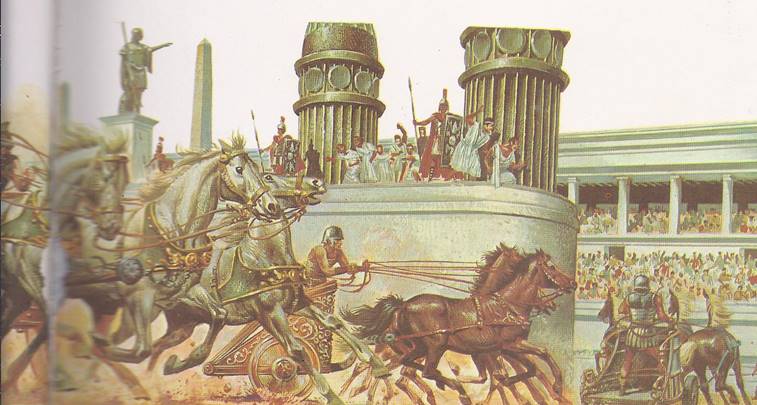

The people flocked to the stadiums and to the racecourse called the Circus and they liked their shows big. Their favorite sports were the cruelest ones –huge mock battles in which the deaths were real and combats of gladiators, men who were sent into the arenas to kill. The Etruscans had once staged such deadly contests to provide their demon-gods with a sacrifice. In Rome, the lights were held for fun.

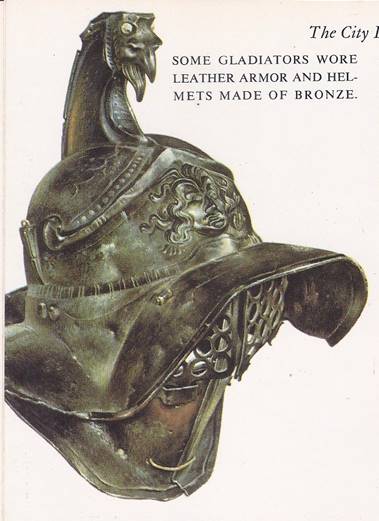

The gladiators were picked slaves, the toughest fighters among the prisoners of war. Barbarians from Africa and the north were in particular demand. In a prisonlike school for gladiators, they were trained for the arena. They were all taught to use the gladius, a short, sharp-pointed sword that could break a man’s arm with one sideways blow or run him through with a thrust. Then the school rented them out to sponsors — the politicians who gave the shows in Rome.

If a gladiator was lucky, he lived through his first fights in the arena. He began to learn to kill with style and to show off his strength to please the crowd. That was important. When the great men in the city got to know his name and placed bets on him, they saw to it that he was pampered by his owner. As he became more famous, his fans showered him with presents. School girls screamed and fainted when he walked into the arena. Nothing could change the fact that winning today meant only a chance to risk his life again tomorrow.

As time went on, the marks of his trade showed on his body — scars, an ear half gone, a broken nose. Sooner or later, a younger, tougher fighter would turn up in the arena. The old favorite would be struck down and the people who had been his fans would shout for the new hero to finish him off. Until that happened, he had to go on fighting, knowing that in all the crowd only one person really cared if he lived or died. That was the sponsor, who got a refund for the gladiators he returned to the school undamaged.

THE SENATE AND THE MOB

A more expensive and livelier game was the “wild beast hunt.” Lions and elephants and other animals from Africa were strange and exciting to Romans. They liked to see them let loose in an arena with a group of prisoners who had to kill them or be killed. The men who planned the shows were always on the lookout for new ways to thrill the crowds. Rival politicians dug into their treasuries to hire more gladiators or wilder animals and still the mob was not satisfied.

The people of the mob ran the Republic with their votes. Hungry and selfish, the mob hated the rich men and the senators, but needed them to live.

The senators, proud and old-fashioned, used their power selfishly. They loathed the mob, but needed its votes and feared its anger. A third group, the knights, had once been Rome’s cavalry; now they were the city’s businessmen. They were rich and willing to buy the votes of the mob or the senators to gain power for themselves. The disputes between the Senate and the people’s assembly often gave them the chance.

At elections, there was violence and bloodshed in the streets. Rival groups and candidates tried to settle political contests with clubs and daggers. Rome still had wise and honest men, but when they tried to speak out they were shouted down by the mob, and the laws they tried to pass were voted down by the Senate. Sometimes they were murdered.

In 133 B.C., Tiberius Gracchus, a veteran officer, proposed a law to give land to his homeless soldiers. With land they could earn a living instead of begging. Not even the most selfish senator could deny that Rome owed them that much, he said. In the Forum, Tiberius told a cheering crowd, “Wild beasts have their lairs, but the men who fight and die for Italy can call nothing their own except the air and the sunshine!” The people’s assembly elected him tribune and the Senate hired a gang to kill him.

CAIUS GRACCHUS

Nine years later, his brother Caius tried again. In the hope that he could frighten the Senate with a show of money and power, he made pacts with businessmen and Rome’s Italian allies as well as with the mob. At first things went well for him. He suggested laws which he thought would benefit everyone and not just the poor. His program for finding usable land and establishing new colonies for the homeless won him the votes of the people. The businessmen and the Italians were pleased when he spoke of projects for building roads and harbours that would make jobs for the unemployed. Everyone agreed with him that the state ought to sell grain at low prices to those who could not otherwise afford to buy it. The people cheered him in the streets and the Senate, truly frightened at last, did not dare to vote against him. Then he began to talk about votes for the Italians. It was time to treat them like proper citizens, he said. Suddenly his business friends were much less friendly and the mob turned on him. Votes were the only valuable thing they had; they did not intend to share them.

Riots broke out all over Rome as the people surged through the streets, howling for vengeance on Caius Gracchus. The senators, no longer afraid, issued an order for his arrest and the mob was delighted to do the job for them. They joined the gang of slaves and thugs which the Senate had sent to hunt him down. When they had him trapped‚ they stood by while he killed himself. Caius’ death was final proof that the mob could not be trusted even to help itself. It would take swords, not votes, to change the laws of the Republic.

From now on‚ when the people and the aristocrats of the Senate turned on each other, they would set out to destroy each other completely. For leaders, they looked to the men who commanded armies. It had always been the rule in Rome that the Senate chose the generals, but in 107 B.C., the people overruled the senators. They picked their own man, Caius Marius, to command the legions fighting against Jugurtha, a rebel king in Africa. Caius Marius was a rough country man, bat a good officer. The people chose him because he promised that he himself would kill or capture Jugurtha and because they were sure that he would never side with the aristocrats.

THE SOLDIERS’ CHOICE

Marius was the soldiers’ choice, too. They called themselves “Marius’ Mules,” for they were a corps of road builders and trench diggers as well as infantrymen. They carried eighty pounds of equipment on their backs when they marched across Africa. So long as Marius led them, they did not complain. He was an old campaigner who ate at their table, shared their hardships and knew war as they knew it. When he took command of the African legions, he began to build a new kind of army. He did not rely on the drafted citizens who had always filled the ranks. Instead, he took volunteers from the penniless men of Rome. To them, the army meant a job. They were loyal to the officer who looked after them, not to the government who often had not. If he brought them victory and kept their stomachs full, they were his for so long as they lived.

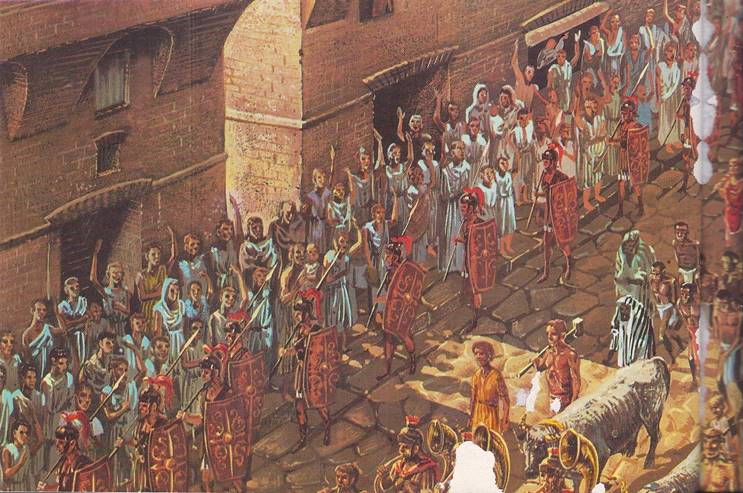

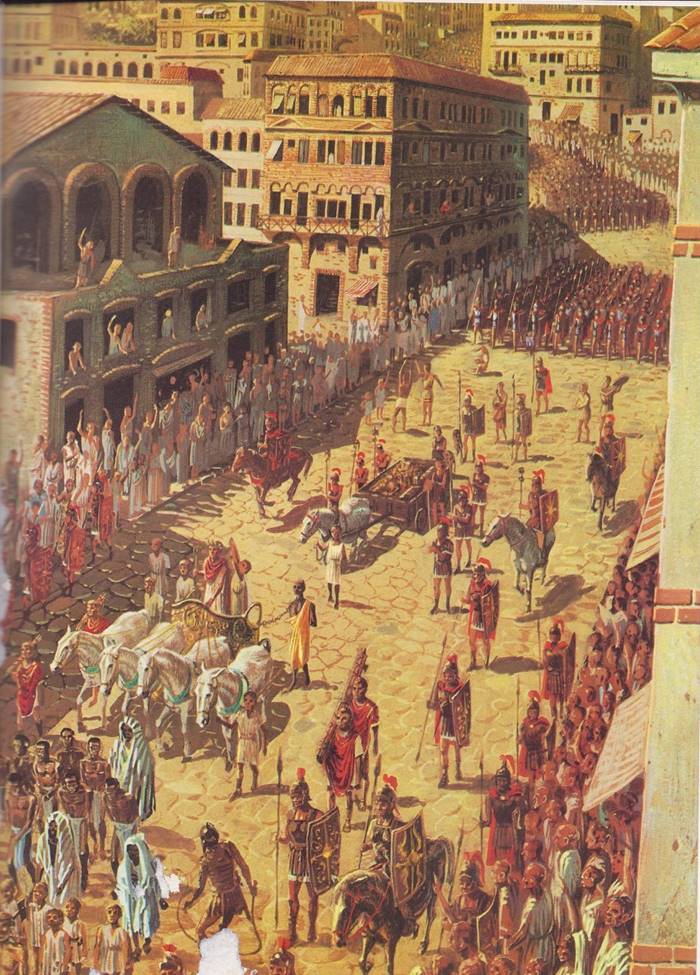

The Roman mob was not that loyal, but, for the time being, Marius was their hero. When he returned victorious from Africa, they awarded him a “Triumph,” the honour that Rome gave to its greatest generals. It was a grand procession, led off by the officers of the city and the senators. They were followed by the wagonloads of booty and Marius himself, riding in a four-horse chariot. He was dressed in a robe of purple, which only victorious generals were allowed to wear. In his hand, he carried the laurel branch that he would place on Jupiter’s altar as a sign of his success in war. Behind him marched his soldiers, chanting a song of victory, while the people cheered and hung garlands of flowers about their necks. It was a day of glory for Marius, but his glory was not complete. One of his officers‚ a man named Sulla, had to be given credit for capturing the African king. Marius had meant to do that himself. His pride was hurt — and he was a man of great pride.

MARIUS AND SULLA

The people did not seem to care who had captured the rebel. They re-elected Marius consul and went on re-electing him for four years. That had never happened before; consuls were supposed to change each year, but the people needed him, because hordes of new barbarians, more fierce than any that had come before, were attacking northern Italy.

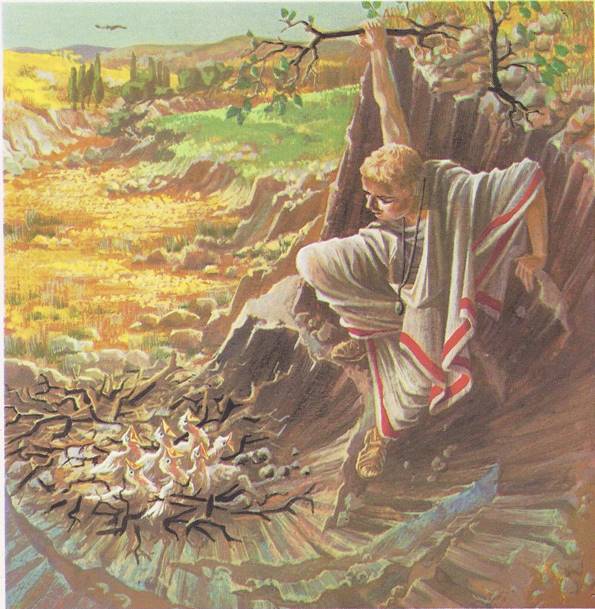

Marius himself was not at all surprised at his honours and elections. He had expected them. When he was a boy, scrambling over the hills outside his village, he had found an eagle’s nest with seven fledglings in it. A soothsayer, the wise man of the village, told him that it was a sign from the gods. He would win greatness seven times. A Roman soldier could win no greater honor than the post of consul-commander. As Marius marched north to face the barbarians, he never doubted that he would come back to Rome victorious. He was just as sure that the Romans would go on electing him until he had been consul seven times.

When he had defeated the invaders and returned to the city, everything seemed to go wrong. The people began to change their minds about him. He was too proud, they said, and he had been consul too many times.

Marius could not understand it. In the field, he knew exactly what to do and when to do it; in the city, his blunt manners only got him into trouble. He had never learned to make fine speeches. He did not know how to deal with politicians. Even so, he was determined to be elected consul again. To win votes, he tried to please everyone, even the senators. The result was that he pleased no one and lost the election. Marius did not take defeat easily. His pride was hurt and he began to talk about revenge. To make matters worse, Sulla, the officer who had stolen his glory by capturing the African king, had become the favorite of the senate.

Suddenly, the Romans needed both Marius and Sulla. The people of the Italian cities were tired of waiting for the right to vote. They tore up the old agreements and declared war on Rome. Marius and Sulla were put in command of armies and for three years they marched up and down the peninsula, fighting the men who had been their allies.

In Asia, an ambitious king, Mithridates, saw that here was a chance to win himself a new Persian empire. While civil war kept the Roman legions in Italy, he sent his troops into Syria and Asia Minor. The governors were helpless to stop them. Mithridates also sent secret agents into the Eastern cities where many Romans had settled. Quietly the agents organized the townspeople. Then, on one day of terror, the Asians attacked the westerners who had come to live among them. They murdered every Roman and Italian they could find — more than 100,000 men, women and children, as well as their slaves.

In Rome, the citizens gasped at the news of the killings. A few weeks later, they had trouble of a different kind. Without taxes from Asia, the Roman treasury was soon all but empty. Millionaires, who depended on the eastern trade, found themselves penniless. The fight about voting began to look rather ridiculous. If Rome lost its provinces, ran out of money and collapsed, voting would not matter very much. The Romans decided to end the civil war and thanks to Mithridates, the Italians were given the full rights of citizenship.

LUCKY SULLA

The next question the Romans had to decide was who should command the army that must be sent to Asia. The Senate chose Sulla, but Marius wanted the command for himself. He was almost seventy years old, worn out, and often unable to control his fits of anger, but his pride was as fierce as ever. He went to the people and asked them to vote for him, against Sulla and the senators they hated. The mob did as he asked, then marched on the Senate, swearing to kill Sulla.

Sulla was too quick for them. He fled the city, but soon came back with his army and took Rome by force. Now it was Marius’ turn to flee and he had no army waiting in the country. Some of his followers left Italy with him, but when his money and provisions were gone, they deserted him. Alone, far from Rome and forced to live in hiding, he nursed his anger until it was close to madness. He dreamed of revenge and the day when he would command a Roman army again. If his courage faltered, he reminded himself of the sign of the seven eagles. Six times he had been consul. He knew that there would have to be a seventh time and he waited.

Sulla, the new commander of the legions, was everything that Marius had never been. He had needed no soothsayers to tell him he would be great. He was Sulla Felix, “Lucky Sulla,” a name he had chosen for himself because he was certain from the start that he was Fortune’s favorite soldier.

It was true that things usually went Sulla’s way. Though he was born poor and his first home in Rome was a cheap room in a tenement, he came from an old, noble family. As a youth, he was handsome, with bright blond hair. He knew Greek, had a quick wit and a way with people. He soon won a place in the politics and society of the city. He had no patience with the mob and was sure that only the Senate could rule Rome. Even so, his soldiers learned to like him. He was bold, fearless and could stand great hardship. When there were no battles to be fought, he liked to drink his wine, tell stories and chase girls like any soldier.

Sulla was too quick for them. He fled the city, but soon came back with his army and took Rome by force. Now it was Marius’ turn to flee and he had no army waiting in the country. Some of his followers left Italy with him, but when his money and provisions were gone, they deserted him. Alone, far from Rome and forced to live in hiding, he nursed his anger until it was close to madness. He dreamed of revenge and the day when he would command a Roman army again. If his courage faltered, he reminded himself of the sign of the seven eagles. Six times he had been consul. He knew that there would have to be a seventh time and he waited.

Sulla, the new commander of the legions, was everything that Marius had never been. He had needed no soothsayers to tell him he would be great. He was Sulla Felix, “Lucky Sulla,” a name he had chosen for himself because he was certain from the start that he was Fortune’s favorite soldier.

It was true that things usually went Sulla’s way. Though he was born poor and his first home in Rome was a cheap room in a tenement, he came from an old, noble family. As a youth, he was handsome, with bright blond hair. He knew Greek, had a quick wit and a way with people. He soon won a place in the politics and society of the city. He had no patience with the mob and was sure that only the Senate could rule Rome. Even so, his soldiers learned to like him. He was bold, fearless and could stand great hardship. When there were no battles to be fought, he liked to drink his wine, tell stories and chase girls like any soldier.

After his trouble with Marius, however, Rome saw little of Sulla’s pleasant side. When his army had brought order to the city again, he had Marius’ friends rounded up and killed. Then he had a law passed that required the people’s assembly to ask his permission before it could vote on anything at all. With these things done, he set off for his eastern campaign, leaving the Senate in charge of Rome. The senators soon ran into trouble. Cinna, a politician who sided with the people, was elected consul. When he took office, he invited Marius to come back to Rome. The Senate, with its general and his army across the Mediterranean, could do nothing about it.

The Marius who returned to Rome was not the man who had won the friendship of his soldiers in Africa. He was old, though every day he went down to the Campus Martius and exercised with the young men, showing them that he was still strong, still an expert horseman. He was bitter, and his dreams of revenge had made him cruel. When he had raised armies to send against Sulla’s forces in the provinces, he built a private army for himself in Rome. He ordered the killing of hundreds of men who were said to be supporters of Sulla or the Senate. Then he began to order executions for no reason at all. One morning, a man who spoke to Marius in the street received no nod from him in return. In a moment, Marius’ soldiers had grabbed the man. After that, if anyone greeted Marius and was not greeted in return, that person was killed. Even his old friends took to dodging around corners when they saw him coming.

The people however, did not desert him. In 86 B. c., he was elected consul again, but his pleasure in that success was ruined by reports that came from the East. Sulla was winning victories. Reports from still other areas told of Sulla’s men defeating the armies that Marius had sent to destroy them. Marius grew sour and silent. Night after night he could not sleep. Then he fell sick; the anger burning in his mind seemed also to burn away his strength. In January, 86 B.C., he died, on the seventeenth day of his seventh consulship.

Three years later, Sulla returned to Rome and a triumphal procession. Up to this time, the victor’s chariot had always followed the city officials and the senators. Sulla rode at their head. This was a difference that everyone noticed and it was an important one. The Senate had already named him dictator of Rome; no man stood over or before him.

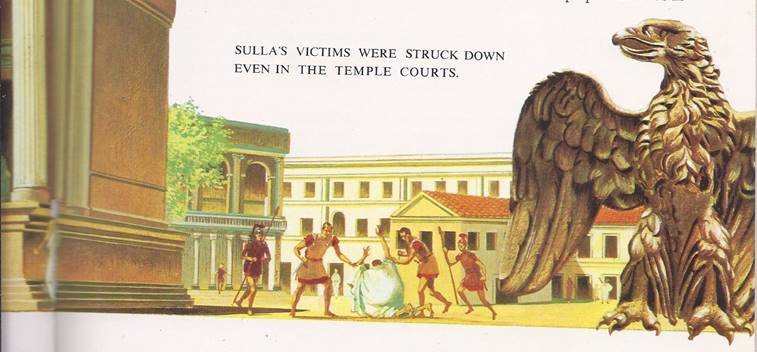

The years had changed him. His hair was no longer golden and his pale skin was marked with red splotches. One witty Greek said he looked like “a mulberry sprinkled with meal.” In the evenings, he was still the jolly soldier who loved a good party. He never forgot his friends, whether they were senators or scoundrels who lounged around the Forum. By day, he was the dictator of Rome, merciless and cruel. While he was unbelievably generous with his friends, he was brutal to everyone else. Now his turn for revenge had come and he ordered the execution of thousands of Marius’ followers. When they were dead, he found other men to kill — men who had had nothing to do with politics. Some were killed because Sulla’s friends owed them money, others because his friends wanted their fine houses or lands.

Sulla discovered a new and easy way to raise money — call a rich man a criminal, execute him and claim his property. Each day a list of “men proscribed as criminals” was posted in the Forum. These men could be legally killed by anyone — indeed, the government would be grateful to the killer. Once the wealthy “criminals” were dead, Sulla’s friends took charge of their gold and possessions. It was such an efficient system that, years later, dictators in other countries would copy it.

A NEW CONSTITUTION

Yet Sulla was always talking about “the good of Rome.” While his henchmen chased down new victims, he worked at his favorite project — saving the Republic. He wrote a new constitution, which he hoped would bring back the good old days of fatherly senators and common citizens who did as they were told. “The laws, not I, Will once again rule the good family of our state,” he said to the people who lived in terror of his orders — and he believed it. It did not occur to him that he himself had shown how little the wishes of the Senate mattered to a man who controlled the army. Nor did anyone dare to tell him that his murders for money had made law and justice a terrible joke. Instead, the Senate thanked him for the line new constitution, which gave it complete power over the commoners. The people said nothing and waited for a general who would write the sort of constitution they wanted, using his sword to make it law. Sulla resigned as dictator, confident that he had patched up the old Republic and that it would run itself again. Of course, he had his soldiers stand by, just in case.

In 79 B.C., he died, greatly mourned by the Senate and the friends he had helped to make so rich. They gave him a splendid funeral. As his body was carried through the streets at the head of his last triumphal procession, everyone cheered — his friends because they honored him, the others because he was dead. On his gravestone were carved the words he had chosen himself:

LUCIUS CORNELIUS SULLA – NO FRIEND EVER DID HIM A KINDNESS AND NO ENEMY A WRONG, WITHOUT BEING REPAID IN FULL.