“IT is impossible to find peace and quiet in this city!” Seneca, in Nero’s Rome for a visit, was not enjoying his stay and he wrote about it in an angry letter to one of his friends in the country. “The room I have rented is right over‚ a public bath and I might as well have taken a bed in the Tower of Babel. When the athletic bathers do their exercises, I hear every grunt as they strain to lift the dumbbells and the awful wheezes as they drop them again. In the ball court, a loud-mouthed coach calls out the score at the top of his voice. Then a rowdy starts a quarrel, a pickpocket gets caught in the act (he howls, of course) and some idiot chooses his bathtub as the place to sing a concert. There is a regular parade of human elephants flopping into the swimming pool, each trying to make a greater splash than the last and a chorus of drink sellers, sausage vendors, pastrymen and hawkers for the restaurants — each of them with his own noisy way of spoiling my rest and interrupting my work.”

A bathhouse, with its pools and game rooms and restaurants and locker rooms, was probably as noisy as any spot in Rome. Seneca would not have found much quiet in any neighborhood in the city. There were just too many people. In the years since Augustus had made Rome the capital of his empire, the city had grown bigger, busier and noisier than ever. In the mornings, when the shops were open and the merchants’ carts went out to make deliveries, it was hard to get through the streets at all. The tenements were jammed full. The great town houses overflowed with guests and slaves. Still the people poured into Rome. The citizens knew that the empire was big and filled with thriving towns, but when they peered out of their windows, it looked as though everyone in the empire had decided to live in the capital.

“QUEEN MONEY”

The newcomers were here to make their fortunes. They had heard fantastic tales of the money that could be made in Rome and some of the stories were true. Freed slaves and unknown merchants from foreign villages had set up shop in the city and had indeed become millionaires. They had moved into splendid houses and were treated as friends by men whose families had been famous in Rome for hundreds of years. They were introduced to the emperor, who made them welcome at the court and they were given important government jobs. No one cared what they had been before. If they were rich, they were good Romans.

“In Rome, everything is the slave of Queen Money,” Horace once wrote. “When a man has piled up enough gold, the world is eager to call him famous, courageous and honest as well as rich — And wise, too? — Wise, too, of course. Or king, if he likes, so long as he has the money.”

In fact, no Roman millionaire quite managed to buy himself a kingdom from the emperor. He could live like a king and there were plenty of people who would tell him he was brave or wise if it meant that a little money would trickle out of his hand into theirs.

Rome and the Romans were very different from what they once had been. Horace said the city had gone mad — money-mad. The race to get rich was only one sign of the change. In the old days, when the city was always at war, the citizens had had no time for anything except fighting to win new land or to keep the land they already owned. All their gold went to pay for ships and soldiers. There were jobs to be done and everyone pitched in. Then came the emperors and the peace that won the Romans the praise of the people they had conquered. In Rome itself, the citizens had money in their pockets and plenty of leisure time. They went on a mammoth spending spree, rushing to enjoy themselves as they never had before. Later, when there were fewer and fewer jobs to be done, passing the time became a job in itself. Rich men gave their gold to find new ways to keep busy. The mob shouted for more shows in the arenas. Queen Money paid the bills, and “More and Bigger” was everybody’s slogan.

Once Cicero had asked if a man could really find pleasure in watching another man being mangled by a huge animal, or a jungle beast being tortured until it died. Now, tens of thousands of Romans, who crowded into the stadiums a hundred or more times a year, would have answered, “Yes!” They wanted naval battles, too, like the one Augustus gave for them and giraffes and elephants as well as lions. They turned the old Greek plays into Roman spectacles. Cicero saw a performance of a tragedy that had 600 mules in the cast. When Horace went to the theater, he complained that there were so many troops of horsemen, war chariots, carriages and ships rattling across the stage that nobody noticed the play.

ROMAN CULTURE AND CRUELTY

In early Rome, when the city was still struggling to hold its own against Carthage, the actors had played good Roman comedies. The citizens listened closely, at least to the jokes. For years, the Romans’ favorite playwright, Plautus, kept them laughing with new plays that told old stories about the pater familiar who was henpecked by his wife and made foolish by his sons, or the bullying officer who bragged about his bravery and ran for his life when a slave boy shouted, “Boo!” The shows were noisy, the comedians made fun of people in the audience, and often their jokes were bad. Then Terence, a young dandy, began to write plays of a different kind. They pleased the young fellows who came home from college in Greece convinced that Rome and their fathers were shockingly old-fashioned and slow-witted. Terence borrowed his stories from the Greek comedies and he filled them with clever speeches and puns that every young Roman tried to imitate. Enjoying his plays meant keeping both ears open. Over the years, more scenery, animals and crowds and fantastic costumes were added to the plays, until the audience grew more interested in what they could see than in what they could hear. Often they could not hear even if they wanted to.

In Augustus’ time, Horace said that the noise of beasts and machines on the stage was so loud that the actors could barely shout above it. Horace lost his temper altogether when a lady sitting next to him clapped for an actor before he had even began to say his speech. His robe was such a pretty new shade of purple, she said.

Nero had added his own touches to the dramas. When the story called for a character to die, he had a prisoner dressed up in a costume, pushed onto the stage and actually killed. Nero also tried to make the Roman theater more Greek. When the mob booed his tragedies because they were too dull, he did not give up. He had his tutor, Seneca, write fine Latin versions of the old tragic stories, which he and his friends acted privately in the palace. Seneca’s plays were good; 1,500 years later, playwrights in Europe were still imitating them.

It was fortunate for the world that Nero enjoyed acting in plays more than writing them. If he had wanted to be a playwright, Seneca’s tragedies might never have been performed at all. The emperor did not like competition, as Seneca’s young nephew, Lucan, learned to his sorrow. Lucan wrote poetry and so did Nero. Lucan’s poetry was better than the emperor’s. When the Romans began to praise the poems Lucan read to them, Nero commanded him never to read them in public again. The young poet was so angry that he joined a plot against the emperor and lost his life.

A wiser poet than Lucan was Petronius, one of Nero’s courtiers. He wrote the witty and wicked sort of verses for which Ovid had been sent into exile. Nero loved them, but Petronius never admitted that he had written them. For the stories, which he called The Satyricon, poked fun at the court and at the courtiers who often made fools of themselves. Petronius was an old friend of Nero’s and knew that the emperor might laugh at a joke one day and take it seriously the next. As it happened, Petronius got into trouble despite his caution. Another man in the court, jealous of his friendship with Nero, began to spread the false rumour that he was mixed up in a plot. Petronius was condemned to death, not for the book he had written, but for a crime he had not done. It would have made another good story for The Satyricon, if he had lived to write it.

There were many such stories in Rome, true stories of envy and murder, of cruelty, money-madness, poverty and fear. In the years that followed Petronius’ death, other writers painted a strange and frightening picture of the city. When Nero had been killed, the evils which should have died with him seemed to live on. While Trajan was fighting his great campaigns in the Danube territory, the poet Juvenal wandered about Rome, pushing his way through the crowds that were thicker than ever. On every side, he saw folly and evil. Rome was the nightmare city, Juvenal said. Wine that sparkled in a golden cup always held the threat of poison. Spies were everywhere; their gentle whispers meant that someone’s throat would soon be cut. In all of the city, Juvenal could find no woman who was good, no man who was honest.

People said that Juvenal wrote with acid instead of ink — he spoke so sharply and never had a good word for Rome. Perhaps it was true that he had soured on life. Perhaps he saw the worst side of the city because that was what he looked for. Tacitus, a historian, seemed to agree with him. Tacitus set out to write the story of Rome and its emperors from Tiberius to Domitian and he called it “a black and shameful age.” Rome’s great freedoms were gone, he said. They had been destroyed by ruthless rulers who forced honest men to keep their mouths and ears shut if they wanted to go on living. Tacitus had good reason to hate the emperors. He had lived through the harsh reign of Domitian, the emperor who punished men for plotting even before the plots had begun.

There seemed to be another side or the story. Tacitus’ friend, Pliny, saw nothing shameful in the Roman world. Pliny was one of Trajan’s officials in the provinces. In the letters he wrote back to Rome, he talked about his work and the life he saw as hectic and busy, but not evil and certainly not unpleasant.

It was puzzling that the two friends could see the same things so differently — but, in fact, they did not see the same things. Tacitus, like Juvenal, spent most of his life in the city. Pliny went to the provinces, away from the court and the mob. The trouble was in the city of Rome itself.

When the emperor Adrian journeyed through the empire, he saw rich land, prosperous towns, and people who seemed contented. When he returned to Rome, he could feel that something here was wrong. It did not show on the face of the city, which was beautiful. Hadrian himself had added a dozen new buildings to the City, and had rebuilt the Pantheon so that it was more splendid than before. On every side, the wealth of Rome was displayed in fine houses, colonnades, shops, theaters and temples. It was the richest city in the world, but far from the happiest. People spent money recklessly, only to find that it bought them little satisfaction. There was ugliness in Rome as well as beauty. Though it was the most powerful city in the world, many of its citizens wed in fear.

The Romans had seen great cruelty — slaves beaten to death, criminals tortured and burned alive and whole towns of Jews or Christians massacred. Such things were a part of everyday life, like the beatings which parents and school-masters gave to children who misbehaved or the killings that everyone cheered in the arenas. Indeed, many Romans thought that the gladiator shows were too tame. They called for lights without armour, so that the gladiators could kill each other sooner. After all, they said, the best part of the show was the moment when a victor stood over his beaten opponent, turned to the crowd and at their thumbs-down signal drove his dagger into the other man’s chest.

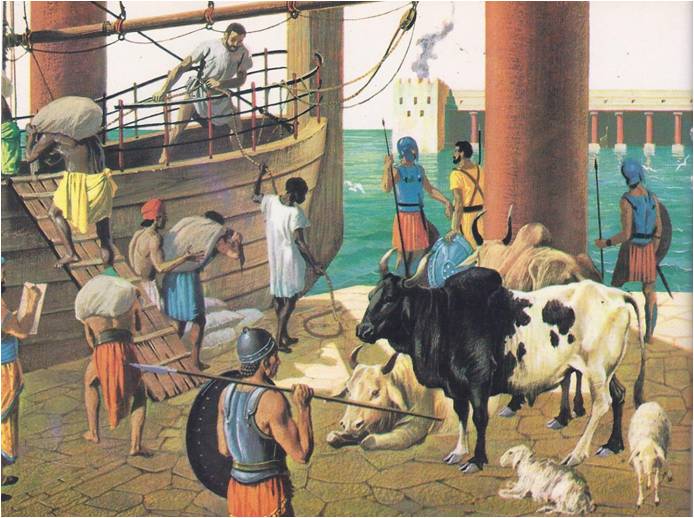

It was strange that the people who built their roads and bridges to last forever were so ready to destroy lives in a minute, but it was so and Rome’s slaves knew it as well as the gladiators did. According to the law, a man was not a man at all once he had been captured and shipped to Rome. He was a “tool that talked,” something his master could use in any way he liked. Animals were “semi-talking tools,” and hoes and ploughs were “silent tools.” For many years, no law protected the slaves from even the cruelest masters. They were beaten with whips or with ropes into which bits of sharp stone had been woven. Runaways were branded. If a master lost his temper and killed a slave, no one interfered. Slaves were cheap; they cost less than good cattle. Some people said that an execution now and then was a good thing. It kept the other slaves in line. Of course, there were Romans who knew that their slaves were men like themselves, whatever the law said and treated them kindly. After Spartacus’ army of slaves had frightened all of Italy, laws were passed to control masters whose tempers were too sharp. Augustus, too, tried to make things easier for the slaves. He disapproved of killing as a punishment and collars with name plates on them were used instead of branding. But a slave’s life was still cheap and thousands of them were worked to death.

FATE AND FORTUNE

The slave who won his freedom could never forget how little his life had once meant. No matter how rich or powerful he became, a little of the old fear still lived inside him. It was a feeling that his children and grandchildren knew, too, and Hadrian’s Rome almost ninety per cent of the people were freed slaves or the descendants of slaves.

Two new gods had come to Rome: Fate and Fortune. They were not the old-fashioned kind of gods with whom a man could strike a bargain. Fate had a plan for every person and every city; no one could change it. Fortune had no plan; she played with the lives of men, changing things as she pleased, for no reason. The people who believed in Fate and Fortune — and most Romans did — could do nothing except wait to see what these most powerful gods had in store for them but they did not wait patiently. They had always watched for signs and omens and now they tried in every way possible to find out what the future would bring.

In the cellars and dark corners of the slums, poor men sought out the hags who were said to know black magic. Some were old country women, who mixed up harmless tonics and remedies from roots and herbs. Others called themselves witches. They brewed love potions and poisons, talked to ghosts, sold curses and charms to ward off evil curses and foretold the future. For the rich, there were astrologers who read the future in the stars and went about their fortunetelling in an up-to-date, scientific way. The scientists at Alexandria had discovered that the movements of the moon had something to do with the rise and fall of ocean tides. After that, it was easy to believe that everything on earth, including the lives of men, was “moved” by the stars and planets. When certain stars shone in the sky, things went well, but others brought evil and bad luck. The astrologers claimed to know the powers of each star, and for a price they gave advice on the good or bad days for marrying‚ taking a journey, doing business, or planting crops. Sometimes they disagreed with each other, but that did not trouble their customers. Everyone was sure that his own stargazer was the one who knew, the truth and even the emperors trusted the wisdom of their favorite astrologers.

NEW GODS FOR ROME

Of course, it was not much good knowing the future if you could do nothing about it. When a man was told to expect the worst, he began to look desperately for hope. The old gods were no help to him. Jupiter and his family were too much like businessmen and they did not seem to care about mankind. The gods of the East, however, were much more sympathetic. They could not make life easier by changing it, but they did promise to lead their followers to a new and better life in paradise after death. In the meantime, their feasts, sacrifices and initiation ceremonies helped people to forget the pain or dullness which they could not avoid on earth.

With drums and cymbals, the priests of Magna Mater, the “Great Mother” of the universe, called her people to wild days of dancing and singing that turned into shrieks of fearful joy. The worshipers of Isis, the calm and beautiful goddess of Egypt, filed solemnly through the streets chanting hymns, or stood for hours in silence, gazing at the lovely‚ pitying face of her statue in a temple. Isis was the favorite god among the women. For the men, there was a more rugged Persian god, Mithra, the Lord of Light. He was also the god of strength and courage, and entire Roman legions dedicated themselves to him. In underground chapels, they celebrated Mithra’s triumph over darkness and evil. The sacred ceremonies were performed by soldiers wearing the masks of the Raven, the Lion, the Sun-Runner and the other characters in Mithra’s story. As the torches burned brighter, the chants became shouts, the rites grew wilder and it was said that sometimes they ended with the sacrifice of a man.

The other gods were usually satisfied with the blood of animals, but their celebrations were as frantic as Mithra’s, especially in the springtime. They were gods who had conquered death and every spring they proved their power by giving new life to nature. Their followers said it was a sign that they, too, would be given new lives when they died. When the first leaves appeared on the trees and plants began to poke through the earth, Rome became a city of festivals. The children of Magna Mater danced out of the city to a grove on a sacred hill, where they held a Feast of Joy that went on for twelve days and nights. On another bill, a noisier, rather giddy group of worshipers chanted praise for Bacchus, the god of wine and crops. He, too, had a story of death and rebirth, which gave his followers hope. So did his wine, which flowed among them as freely as the Tiber.

In the city, meanwhile, the Ship of Isis was drawn through the streets at the head of a gaudy procession of musicians and merrymakers in masks. The launching of the ship marked the start of a carnival. The revelers in their smiling masks danced and sang and forgot that the world could be hard. “I am what is, has been, and shall be,” Isis had promised. It was a comfort to know that the past and future of mankind belonged to a goddess so loving and beautiful. “I conquer Fate and Fate obeys me,” Isis said. Like the joyful people on the hills, the men and women laughing in the streets of Rome knew that cruelty, hunger and pain did not matter. Such things would only last for a little while, until death opened the door to a new and better life.

CHRISTIANS AND PHILOSOPHERS

The Christian god also offered the promise of life after death. He had many followers in Rome now, though they did not celebrate their festivals in the streets. The Christians usually met in secret. It was dangerous to attend their meetings, because they, like the Jews, refused to call the emperor a god. The people who worshiped Isis or Mithra or any of the other eastern gods did not have that problem. They could worship the emperor of Rome, too, and as many other gods as they liked. Often they paid their respects to several of the gods just to be safe.

There were some Romans who did not look to the gods for safety or hope. Like the wise men of ancient Greece, they turned instead to philosophy to find the answers to their most troubling questions. Of course, Greek wisdom was not as easy to live with as Greek statues were. Philosophy asked much of a man and gave back little that the world could see. It took discipline, too and discipline was no longer a Roman practice.

Nero, who was eager to be Greek in everything, did manage to find a philosophy that fitted him quite comfortably. Epicurean philosophy, it was called. Nero said that it taught the lesson, “Eat, drink and be merry, for tomorrow you die.” When he was dead, no one could deny that he had proven the truth of the lesson. He had worked hard at enjoying himself and his enemies had seen to the rest. Apparently his tutor, Seneca, had been afraid to tell him that he was completely wrong about Epicurean philosophy. It was supposed to teach people to enjoy things wisely, without overdoing anything. Or perhaps Seneca knew that, for Nero, philosophy, like poetry, would always mean what Nero said it meant.

Seneca himself had other ideas about philosophy. He was a Stoic, a follower of Zeno of Athens and he believed that true wisdom gave a man the strength to meet his fate nobly, without flinching. Seneca’s strong will helped him to become the most powerful adviser in the palace. He had the courage to give up his power and to plot against the emperor when he knew that it was for the good of Rome. When Nero condemned him to death, he did not wait for the executioner. He said good-by to his friends, finished the work he had at hand, saw that his accounts were in order and took his own life — with the same proud calmness that he would have shown if he had been accepting a gift of thanks from the emperor.

“My duty is to act the part assigned to me well.” That was the rule by which the Stoics lived and Seneca died. The man who said it first was Epictetus, a teacher of the emperor Trajan and a friend of the emperor Hadrian. When he had first come to Italy from Phrygia, he had been one of a boatload of slaves. He was sold to a rich freedman in the court of Nero. He was not a good buy, for he was young and crippled, but his new master thought that he might make something of him. He seemed bright and, though he bore his troubles patiently, he carried himself with pride.

Epictetus was sent to school and there he learned about the philosophy of the Stoics. The part of a slave and a cripple was not an easy one to play without complaining. Epictetus grew in courage and wisdom, until his master was so impressed that he set him free. Then Epictetus opened his own school and some of the greatest men in Rome came to him as humble pupils.

Fate assigned a very different part to another Roman Stoic, Marcus Aurelius. No one could set him free, for he was an emperor. He was one of the two chosen by Hadrian from among all the eager generals and statesmen. It seemed to Hadrian that young Marcus had spent his life preparing to take on the most difficult job in the world — ruling Rome. As a child, he had trained himself so strictly that his mother had had a difficult time persuading him to sleep on a bed of sheepskins instead of the bare ground. A few years later, he began to study the teachings of Epictetus. When Hadrian first met him, Marcus was still a boy, but already he had won a name for seriousness and bravery. Hadrian was certain that this boy could grow up to be the wise commander that the troubled Romans needed. So he chose as his own heir a gentle, elderly statesman, Antoninus Pius, and asked him to adopt Marcus Aurelius as his son.

For the first time, Rome was ruled by men whose one interest was the good of all of the people. Old Antoninus was kind and just. In the twenty-three years of his reign, from 138 to 161, he taught the Romans to forget the fears which they had learned in the time of Nero and Domitian. True to his promise to Hadrian, he made young Marcus his junior partner a strong right arm to guard his justice.

THE BARBARIANS ATTACK

When Antoninus died, Marcus Aurelius had become the man of wisdom that Hadrian had hoped he would be. He accepted the responsibilities of the empire with all the nobility and courage of his philosophy. In his little book, Mediations‚ he wrote the command which he gave to himself each day: “Every moment think steadily, as a Roman and a man.”

Rome needed a ruler with such strength, for in 167, the sixth year of Marcus’ reign, the two centuries of the great Peace of Rome came sharply to an end. Barbaric German tribes broke through the border fortifications and poured down into Italy. They were driven back, but new wars broke out in the north. Then attacks along the eastern frontier showed up the weakness of the defenses which Hadrian had labored to make strong. The attackers were more powerful than they had been before, and when one of their armies was beaten, another turned up somewhere else along the frontier.

For the rest of his life, Marcus Aurelius hurried from the Danube country to Asia and back, fighting to hold the line that meant the difference between peace and the end of the empire. In 180, he died in Vienna, still on campaign.

His son, Commodus, whom Marcus left to rule Rome, was a braggart with a coward’s cruelty. Proud of his strength, he fought in the arenas with the gladiators. His opponents were carefully chosen and somehow they were never the best fighters. After he had been emperor for a year or so, Commodus could boast that he had killed thousands, using (he always said) his left hand only. This noisy hero ran through all the money in the treasury, earned the hatred of his people, and finally, in A. D. 192, was assassinated. He was strangled by his wrestling teacher at the order of the captain of the Praetorian Guard.

Meanwhile, the borders were crumbling. The Romans went on spending their money and, like their late emperor, they gloried in their strength — a strength they no longer possessed.