In 1492, young Giovanni de’ Medici bade farewell to his father, Lorenzo the Magnificent and left Florence to take his place in Rome among the cardinals of the church. At sixteen, Giovanni was a nobleman in the court of the pope, a man of influence and power. That was fortunate, for when Giovanni was eighteen, his family’s power collapsed. The Florentines drove the Medici from their city and Giovanni, who had come home for a visit, narrowly escaped being stoned by the citizens who once had cheered him. As he crept out of the city, disguised as a poor friar, he swore that he would one day return in triumph. First, he thought, he must look to his career in the church. Whatever the Florentines did, he was still a cardinal and in the papal court there were many ways for a clever man to rise to greatness. When he had crossed the Tuscan border, Giovanni threw off his humble disguise, put on the crimson robes and red hat that marked him as a “prince of the church” and took the road that led to Rome.

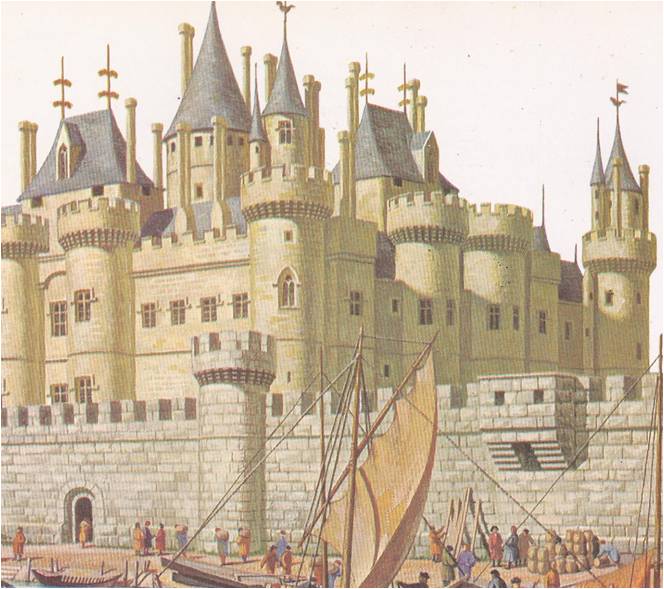

The young cardinal was not alone in hoping to make his fortune in Rome. Indeed, the old city teemed with ambitious men of every sort — scholars and scoundrels, diplomats and spies, millionaires and fortune-hunters, priests and professional murderers. Rome had known every sort of splendour and evil. Memories of unmatched elegance and unbelievable cruelty lingered in the ruins of temples and arenas built by ancient emperors. Grim fortress-houses were reminders of an age of violence, when the bloody feuds of rival clans of nobles had turned Rome into a ghost city. Now there were new mansions, palaces and lofty churches. A new magnificence had come to Rome with the gold that poured into the papal treasury from every country in Christendom.

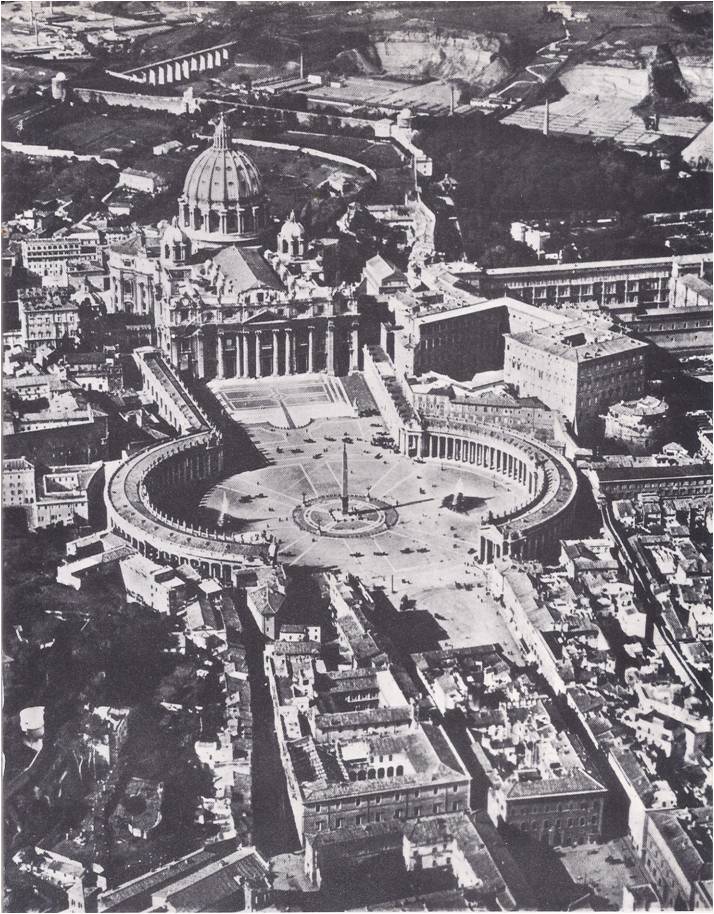

Rome was the pope’s city. Life in Rome, which once had centered about the Roman emperors, now centered about the leader of the Church and his court at the Vatican Palace. When a pope died and the cardinals met to choose a new pope, all Rome held its breath. For the ways of the Church and business and politics, the work of scholars and artists and the very safety of the city depended on the man the cardinals elected.

The popes who came to Rome in the Renaissance were men of the world as well as men of God. To hold his own among the ruthless princes of Italy and Europe, a pope had to deal in politics and power. He had to control lands and cities — the States of the Church — and to display his power with great buildings and a splendid court. He was a diplomat, a finance minister and sometimes a general. He took an interest in painting and sculpture, the most up-to-date learning, and occasionally the most up-to-date revels. Pope Nicholas V, a scholar and a collector of manuscripts, had been Cosimo de’ Medici’s chief librarian and he founded the great Vatican Library. When Pius II, a brilliant student of the new learning, came to power in 1458, every ambitious man in Rome rushed to imitate his elegantly phrased Latin speeches and essays. Twelve years later, the Romans traded their well-turned phrases for well-made clothes, for the new pope, Paul II, was a rich and elegant Venetian who collected finery and jewels.

Not every pope brought learning or gaiety to Rome. Some, like Pope Sixtus IV, were plotters and tyrants. Sixtus’ scheme to kill Lorenzo the Magnificent and overthrow the Medici was only a part of his plan to make himself the master of central Italy. With the help of his warlike nephews, he won the popes a place among the great rulers of Europe. He also won himself the hatred of the people and at his death, the city exploded with riots. The cardinals could bring peace only by choosing a new pope who was so peaceable and so far from brilliant that no one could suspect him of scheming: Pope Innocent III. One of his friends said that he was “not wholly ignorant.” Innocent was wise enough to win the favor of the Romans by adding new buildings to their city. He won the favor of the rest of Italy, too, by letting Lorenzo de’ Medici advise him on foreign affairs. It was he who made Lorenzo’s son a cardinal. However, when the young Cardinal Giovanni came to Rome, seeking to win a place of power in the Church, it was not his father’s friend who welcomed him to the papal court. Pope Innocent was dead and in his place was Alexander VI, a pope as ungodly, tyrannous and sly as any the Church would ever know.

“Alexander,” wrote Machiavelli, “never did anything but deceive men.” Certainly, he deceived the Romans. As a rich and ambitious cardinal from Spain, he had given them free shows and bullfights. When he became pope, his coronation was a magnificent spectacle and the Romans cheered him with wild enthusiasm. Of course, he did take a rather firm hold on the city government and it seemed a bit odd that, instead of palaces or churches, he put up a great fortified castle. At least his officers kept order in the streets. For the first time in years, it was possible to go about the city at night without running the risk of being robbed or murdered. With the help of his children, two handsome sons and a pretty, blonde daughter, Alexander made his court in the Vatican a gay and elegant place, as famous for its chefs and dancers as for its scholars and churchmen. The pope himself grew famous for his good humor. “Rome is a free city,” he said, “where everyone can say what he likes.”

When Alexander’s older son was mysteriously murdered, grief worked great changes in the good-humoured pope. He ignored state business, refused to eat and sobbed so noisily that his cries could be heard in the streets outside his palace. He called the cardinals together and weeping and tearing his robes, he fell to his knees and confessed his sins. “We are resolved to amend our ways,” he said, “and to reform the Church.”

After the pope’s grief had passed, he began to act more like himself. He forgot the reforms for the Church and remembered that he still had one son, one heir to whom he meant to leave an empire. That son was Cesare Borgia, Machiavelli’s example for princes. The pope put Cesare in charge of the papal armies and sent him out to conquer the States of the Church. When Cesare needed money for more troops, Alexander sold church offices — there were many men who would pay well to be appointed as bishops or cardinals. When Cesare needed allies, Alexander worked his diplomatic wiles on the king of France, who was only too pleased to be invited to invade Italy.

END OF THE BORGIAS

The Romans’ delight in the pope turned to loathing and the city buzzed with tales of the evils of the Borgia pope and his children. It was said Cesare had arranged his brother’s murder and it was known for certain that he had killed his sister’s husband in a quarrel. The Borgia killings, said the gossips, were not limited to the family. There were, for instance, the strange, sudden deaths of wealthy churchmen. Men bought appointments as cardinals, grew rich by selling lesser offices and then they died, leaving their palaces and fortunes to the pope. Surer such convenient deaths were not accidents. Everyone talked about slow poison,” which took several days to work so that the deaths, when they finally happened, seemed natural. It was the pope’s daughter, Lucrezia Borgia, who mixed the poisons for her father’s victims, the gossips said. They went on to describe in great detail the wild and shocking parties that she gave in the Vatican Palace. It was something of a disappointment for the Romans when Lucrezia was happily married to the son of the Duke of Ferrara and proved to be only a pretty, well-mannered girl.

Most of the stories told about the pope and his family were probably untrue, but the Romans were willing to believe any evil whispered about them. When Alexander and Cesare were taken ill only a few days after they had dined in the garden of a cardinal’s country mansion, the gossips put together the darkest tale of all. The pope or Cesare, they said, had mixed a dose of the “slow poison” into a bottle of wine, meaning to give it to the cardinal. However, Alexander’s butler, who served the wine, had made a mistake — or perhaps he had been bribed.

In spite of the gossip, it was probably malaria, not poison, that struck down the pope and his son. Thousands of Romans suffered from the disease that summer and the Borgias’ long evening in the dampness of the cardinal’s garden might well have brought on the fever. In any case, they were desperately ill and after thirteen days the pope died. The Romans rushed into the streets to celebrate, while the gossips added one last tale to all the others. They said a little devil had been seen scampering into the Vatican Palace; he had come, of course, to collect Alexander’s soul.

The new pope was a follower of the Borgias, but he lived for less than a year. Soon after his death, Cesare Borgia was killed in battle. The Romans breathed a sigh of relief and the cardinals tried to find a strong but honest leader for the Church. They chose Cardinal Julius della Rovere. Long an enemy of the Borgias, he was so blunt and outspoken that it seemed impossible he would try to deceive anyone. In 1504, he was crowned Pope Julius II.

Pope Julius did indeed lack Alexander’s slyness and his cool head for diplomatic treachery. He also lacked his good humor. Julius was stern, impatient and when he was angry, which was often, he could be rude and noisy. Like the Borgia pope, he was more concerned with power than with religion, but he was an Italian, with an Italian’s hatred of foreign troops in Italy. When Italy’s other rulers proved timid about dealing with the French invaders, Julius set out to do the job himself. He put on a suit of armour, rode into battle and soon all Italy knew his war cry: Fuori i barbari, “Drive out the barbarians!”

The pope in armour was a startling sight. He was over sixty, overweight and at first the soldiers chuckled at him. They soon learned to cheer him instead, for Julius had courage and could fight vigorously. For ten years, he kept the Italians fighting wars. He freed their peninsula of foreign soldiers and made his States of the Church one of the five great powers of Italy.

It was Rome’s good fortune that Julius was as enthusiastic about art as he was about war. He set out to improve the city’s appearance, hired more than a hundred artists, architects and brought the Golden Age of the Renaissance to Rome. When his engineers reported that the ancient Basilica of St. Peter, the central and most revered church in Christendom, was in dangerous need of repairs, Julius commanded them to tear it down. He would build a new St. Peter’s, he said, the biggest, most magnificent church in the world. To design it, he chose Donato Bramante, one of the new architects who loved the graceful shapes of the old Greek and Roman buildings. Bramante had already rebuilt Julius’ summer palace, the Belvedere and made it one of the loveliest buildings in Rome, a perfect setting for the pope’s prized collection of ancient statues.

Julius always seemed to choose the right man to carry out his projects. Then he would coax, encourage and bully the artist into doing his finest work. In 1508, he gave the job of decorating his private rooms in the papal palace to a young cousin of Bramante’s, a painter called Raphael. Raphael was only twenty-five and though he had won a name for his lovely paintings of madonnas, he was not among the leading painters of Italy. Indeed, when he came to Rome, he was only one of several artists hired to paint the walls and ceilings of Julius’ rooms. Julius kept a sharp eye on his work. Then, one morning, he marched through the half-finished rooms and ordered all the artists to stop working. He had a new plan for these rooms. Raphael would paint them all. Raphael begged him not to destroy the other artists’ paintings, but Julius had made up his mind. The walls and ceilings were whitewashed and Raphael went to work. It turned out that, as usual, Julius had chosen the right man.

In the first of the rooms, the Stanza della Segnatura, or Signature Room, where the pope met foreign dignitaries and signed official papers, Raphael painted four masterpieces. On one wall, he painted saints and apostles; on another, poets and musicians; on the third, lawgivers, including Julius himself; on the fourth, the world’s great philosophers gathered about Aristotle and Plato. Together, the paintings seemed to sum up the wisdom and art that were the glories of the Renaissance.

Rome had never seen such painting, nor such a painter. Raphael’s touch was quick and sure. He was no Leonardo who had to struggle and wait and ponder and make changes. He loved his work and he loved life. He enjoyed the warm companionship of friends, the charms of pretty women, expeditions, parties. When Rome’s great churchmen and bankers learned of the work he was doing for the pope, they rushed to persuade him to paint for them, too. Somehow, Raphael had time for everything, including acts of kindness that won him a name as the most good-natured man in the city.

A very different sort of man was the artist to whom Julius entrusted his most difficult projects. Michelangelo Buonarroti was moody, ill-tempered and almost friendless. His art was agonizing labour for him and life seemed to have been planned for his own special annoyance. In his youth, he had won a place in the household of Lorenzo the Magnificent — and a broken nose for speaking too frankly to another of Lorenzo’s artists. At twenty-one, when he came to Pope Alexander’s Rome, he was as skillful as any sculptor in Italy, but he nearly starved for lack of work. All that he asked of his patrons was the time it took “to find the figure” in a block of marble by chipping away the stone bit by bit. People were reluctant to hire an artist who worked so slowly. Meanwhile, Michelangelo’s family– his father and brothers — desperately needed money. They were, they wrote, temporarily out of jobs. Somehow, they usually were.

Michelangelo’s one loyal patron in Rome, a banker for whom he carved a cupid, at last persuaded the French ambassador to order a statue from the young sculptor. The ambassdor agreed only when the banker had signed a guarantee that Michelangelo would finish the figure within a year and that it would “be the finest work which Rome today can show.” Michelangelo lived up to that guarantee. He finished the statue of the dead Christ and his mother, called the “Pieta,” and it was indeed as fine a sculpture as any Rome had seen.

The “Pieta” brought Michelangelo much fame, but not enough money to satisfy his family’s needs. So in 1501 he went home to Florence and carved a statue for the Council of the Republic. It was another masterpiece, the figure of the boy “David.” For this job, which took two and a half years, the penny-pinching councilmen paid Michelangelo about $5,000, a bargain price for a statue that would one day be as famous as any in the world. When they asked the artist to do a huge wall-painting in their council-chamber, he had no choice but to agree. He disliked painting as much as he loved carving, but he needed the money.

The artist had just completed the design for the great picture when the council received a message from Pope Julius. Michelangelo was needed in Rome at once. The councilmen wanted to have their wall-painting. Julius, they said, had no right to interfere, no right at all. When they had impressed each other with their indignation, they hurried Michelangelo off to Rome, for not a man of the council dared stand up to the pope’s famous temper.

Pope Julius greeted Michelangelo warmly. He had, Julius said, a very special project in mind. He wanted a tomb for himself, a monument so big and so splendid that even after his death Rome would not be able to forget him. Michelangelo nodded and went away to think and make sketches. He returned with the plans for a marble monument two stories high and decorated with forty statues. It would take years of work, cost a fortune and use up tons of marble. Julius was delighted. Here, at last, was an artist whose ideas were as grand as his own. He approved the plans, gave Michelangelo some money and sent him to the quarries to buy the marble he would need.

So began the extraordinary partnership between an artist and a pope. Michelangelo and Julius were indeed alike in loving grand projects and in letting nothing stand in the way of the things they meant to do. They also had the same angry temper, the same unbending pride. Over the years, they argued, shouted, threatened each other, swore time and again never to speak or meet again and together gave Rome its greatest masterpieces.

When Michelangelo returned to Rome with the marble for the monument, Julius was busy planning a campaign against Bologna. He had little time and no money to give to Michelangelo. The artist waited, grew impatient, demanded to see the pope and was turned away from the papal palace by a servant. In a fit of fury, he went home to Florence. For months. Julius bombarded Florence with angry messages, which Michelangelo stubbornly ignored. Finally‚ after conquering Bologna, Julius wrote to Michelangelo asking him to come there to make a great bronze statue to mark his victory. Michelangelo agreed. In fact, he was almost afraid to refuse. He needed the money, and besides, he wanted to make the statue.

In Bologna, Julius frowned and grumbled, but he silenced a bishop who began to berate Michelangelo for his disobedience. The artist shrugged off the pope’s forgiveness. He showed his gratitude by making a bronze portrait of Pope Julius at his fiercest. When it was completed, Julius Called him to Rome to discuss another grand project.

“The monument?” Michelangelo asked. No, it was something else — the vast ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, Julius had decided that Michelangelo would paint it. Michelangelo refused. He was a sculptor‚ not a painter. Surely Raphael was the man for the job. But Pope Julius did not want Raphael. He pleaded, commanded and threatened, then offered to pay so high a fee that Michelangelo could not turn it down. “This is not my trade,” the artist mumbled and went home to start his sketches.

THE SISTINE CEILING

For the next four years, Michelangelo worked at the trade that was not his. Each morning, as soon as it was light, he climbed up the scaffolding that towered to the ceiling, sixty-eight feet above the floor of the Sistine Chapel. He mixed his colors, consulted his drawings and charts of the 10,000 square feet of ceiling and he painted. Sometimes sprawled on his back, sometimes crouched and never comfortable, Michelangelo struggled and cursed and painted.

There were 343 bodies to do, 343 heads, nearly a quarter of an acre of background and no assistant he would trust to touch any of it. At dusk, he hauled himself down the scaffolding and went home to rest. His body ached and he spent so much time with his head tilted up to see his work that he could read only by holding the book above his head. The one reward for the hours of painful labour was the fact that up on his scaffolding he could be alone with his work. No one interrupted him there, no one that is, except Pope Julius. Every so often the pope had himself pulled up in a basket. He peered and poked, admired the work that was done and always demanded impatiently, “When will it all be finished?”

Michelangelo’s answer, like Julius’ question, never changed: “It will be finished when I shall have done all that I believe is required to satisfy art.”

Then the pope would grow angry. Once, his servants waiting below heard him bellow, “Do you want me to throw you from this scaffolding?”

In October, 1512, Michelangelo stopped painting at last. He was not really satisfied, he said, but he had done what he could. The scaffolding was taken down and for the first time, it was possible to stand on the floor of the chapel and see the painting which he had spread across the great ceiling. He had divided the space into more than 100 panels, each a separate picture, but so skillfully planned, it formed a part of one great design. The stories these pictures told were parts of one great story, the story of God and the world be made. Adam receiving the life-giving touch of the Creator, Noah, Moses, prophets, David triumphing over Goliath and Christ, the Prince of Heaven — these were Michelangelo’s subjects. In his youth, he had heard Savonarola’s sermons thundering in the old Duomo at Florence. He had never forgotten them. His religion was a religion of strong feelings and the figures on his ceiling were as powerful as those he carved from stone.

The Sistine Ceiling was a triumph, for the painter and for the pope who had forced him to paint. Michelangelo, too weary to make much of his success, was merely glad that he could go back to being a sculptor again. Julius, though he was old now and often ill, had gone to war again, for the French invaders had returned.

In the summer of 1511, the pope was struck down by a fever. For three days he lay unconscious and his death seemed so certain that the cardinals began to gather to elect a new pope. On the fourth day, Julius sat up. Against the strict orders of his doctors, he drank a large cup of wine. To everyone’s surprise and the bitter disappointment of his enemies, he began to get well. By autumn, he was almost himself again. When spring brought good fighting weather, a Spanish army arrived to help him drive the last of the Frenchmen he hated out of Italy.

A MEDICI POPE

In January, 1513, Pope Julius’ great strength at last gave out. He had won his battle, chased out the “barbarians” and he was content to die. The Romans thronged to his funeral and stood for hours waiting to kiss the feet of his corpse. For all of his ill temper, Julius had done much for them and their city and they hoped that the cardinals would make as good a choice again.

The man the cardinals did choose was young — just thirty-seven — and he came of an old and honored Italian family. He had been one of Julius’ most trusted advisers. During the war he had served as the pope’s representative to the Spanish commanders and with the help of the Spaniards he had returned in triumph to his family’s city, a city which once he had fled in fear of his life. He was Giovanni de’ Medici, a boy no longer, grown a bit fatter and a great deal wiser. In March, 1513, he left Florence and took the road to Rome, just as he had so many years before. This time he went to be crowned as Pope Leo X.

The Romans could not have been better pleased if they had elected the new pope themselves. The new pope was generous and friendly, as even-tempered as Julius had been fierce. Best of all, though he remembered it was his duty to guide men toward heaven, he saw no reason why they should not enjoy their time on earth. He certainly meant to do so himself. “Since God has seen fit to give us this great office,” Pope Leo said, “then let us enjoy it.” Or so the story went in Rome.

Leo loved to have comforts in his palace, fine clothes on his back and the music of viols and lutes to entertain him while he ate his well-cooked and enormous meals. He loved hunting and indeed, he spent so much time in his hunting boots that his master of ceremonies complained that pilgrims could never kiss his feet. Leo kept jesters in his court as well as churchmen, attended plays and balls as well as mass. He taught Rome to live in splendor, to spend its money lavishly and the Golden Age that had begun with Julius glowed more brightly than ever.

Julius had made Rome a centre for painters, sculptors and architects. Leo, an enthusiastic humanist, filled the City with poets, scholars‚ historians and philosophers. He hired the finest professors for the University of Rome and an army of bookmen to look after the priceless collections in the Vatican Library. Ofcourse, he kept the artists busy and did his best to hurry the building of the new St. Peter’s.

Work on the new Church had gone slowly. The architect, Bramante‚ had died and the papal treasurers had been hard pressed to raise money to meet the enormous building costs. Leo ordered the cardinals and bishops to double their efforts to collect funds from Church members in Europe, then appointed Fra Giocondo and Raphael to work together on the designs. Unfortunately, Fra Giocondo was very old and Raphael was no architect, so little was actually done.

Raphael was, however, exactly the kind of man that the pope liked to work with — a genius who enjoyed his work and never made problems. Leo would trust no one else with his favourite projects. He asked Raphael to complete the wall-paintings he had begun in the Vatican Palace. He put Raphael in charge of decorating the new galleries in the palace courtyard, named him Superintendent of Ancient Buildings and had him design ten magnificent tapestries for the Sistine Chapel. While he worked at these jobs, the young artist found time for dozens of other projects. He designed jewelry and medals, perfume boxes and bronze plaques. He painted portraits; decorated mansions with wall-paintings of cupids, nymphs and goddesses; and painted his matchless religious pictures. Light-hearted and always lively, he dashed from one assignment to the next, from dinner parties to all-night balls and seemed determined to squeeze twice as much life into a day as any other man. On April 6, 1520, at the age of thirty-seven, he suddenly died.

LEO AND THE EMPEROR

Rome was stunned by the news. On the day of his funeral, Pope Leo led the sad procession that included every artist in the city. Many of the sculptors and painters were bitter rivals, but they marched and mourned together, for Raphael had been a friend to them all.

One great artist was not in the city to join the mourners. Michelangelo had gone home to Florence after the death of Pope Julius, and Pope Leo had made no effort to call the moody short-tempered artist back to Rome. “He is an alarming man,” Leo said, “and there is no getting along with him.”

It was Leo’s policy to “get along” with everyone. It was a pleasant policy, a safe one and one that was most necessary for a pope who had to deal with powerful foreign monarchs. Hot tempered Julius had set the Spanish against the French and had left to his successor the problem of keeping peace between the two powers, or at least keeping them out of Italy, but there was no peace and the Italians lived in constant terror of invasions. Most of Europe was divided between two jealous rival monarchs — Francis I, king of France and Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, lord of the Netherlands and king of Spain and Naples. Both had their eyes on Italy. When Francis reclaimed Milan at the northern end of the peninsula, Charles rushed to strengthen his Spanish garrisons at Naples in the South. The Italians frantically made treaties, first with one monarch, then with the other and Pope Leo chatted and charmed and schemed to “get along” with both.

In 1518, Leo wed his nephew to a French princess, hoping that the marriage would provide a friendly diplomatic link, much stronger than a treaty, between the pope and the throne of France. In 1519, the princess died in childbirth, her husband died of a fever and all that the pope had to show for his well-made plan was their baby, little Catherine, a girl-child and useless diplomatically.

So Leo turned away from France to try his luck with Charles V and asked the emperor’s help in quieting a noisy church squabble in Germany. A German monk named Martin Luther had been making a great to-do about church reforms and was calling for the pope to stop the sale of “indulgences.” These “indulgences’ were pardons for sins — almost letters of admission to heaven, said the churchmen who peddled them. They could be purchased before or after the sin had been committed, which was a great convenience. Of course, some old-fashioned churchmen questioned whether these pardons were worth any more than the paper they were written on and Leo himself sometimes had a few doubts about them. However, he allowed them to be sold in order to raise money for the new St. Peter’s.

In any case, Leo did not intend to let a little monk tell him how to run the church. When Luther and his followers began to grow troublesome, Leo threatened to excommunicate them. When they defied him by setting up a church of their own, he decided it was time for stronger action. Luther, he was certain, was just another thunderer, like Savonarola and his power over his followers would fade, as thunder did after a summer storm. To be safe, he asked the Emperor Charles to set his soldiers on the Lutherans.

The emperor, however, was not anxious to involve himself in a religious feud. He felt, too, that the pope had underestimated Luther’s power. He refused to help at all unless the pope would offer him something in return. Leo finally agreed to sign a secret treaty, promising his help in a Spanish campaign to drive the French from northern Italy.

That was the end of “getting along,” of working for peace; the pope had been forced to take sides. Yet the treaty seemed to do much good. An army of Spaniards and Germans sent the French scrambling for the Alps and home. A great parliament of German states, led by the emperor, solemnly voted its disapproval of Martin Luther. Money for St. Peter’s poured into the papal treasury. At his death, in 1521, Pope Leo was certain that he had done as much for Italy with his diplomacy as Pope Julius had done by riding into battle.

The Romans agreed and loudly lamented the loss of a pope so noble and good-humoured. The wits, remembering his extravagance, summed up his story in another way: “Leo gobb1ed up three papal treasuries,” they said, “the treasury of Julius, his own, and that of his successor.”

DISASTER FOR ROME

The successor, Pope Adrian VI, was far from a spendthrift. A solemn, sober-minded German, he believed in church reforms and not in art, poetry, comfort, or pleasure. Adrian demanded that the churchmen stop spending money and live simply. They must give up wearing elegant clothes. They must have no jewelry or gilded knickknacks, no gold or silver dishes on their tables and certainly no nymphs or goddesses on the walls of their palaces. Within eight days of his coronation‚ the new pope had dismissed every artist working on every Roman building under his authority. The painters and sculptors packed up and drifted away from the city. The musicians, poets and actors also left. Rome began to seem very dull and it was a great relief to everyone when Adrian died a little more than a year after he had been crowned.

The cardinals, determined not to choose another reformer, looked about for a man whose religion and tastes were safely up-to-date. In Florence they found another Medici, Pope Leo’s nephew, Cardinal Giuliano. In 1523, they crowned him Pope Clement VII. Rome was delighted. The churchmen put on their jeweled gowns and got out their golden knickknacks. The painters, poets and the rest hurried back to the city and Clement set them all to work again; he even managed to get along with Michelangelo.

These hopeful beginnings led to a series of disasters. In Clement’s time, the Lutheran revolt spread across Europe, breaking the Church into bitterly quarreling fragments. The wars of France and Spain raged in Italy and the Italians, leaderless and fearful, squabbled among themselves and grew weaker than ever. Clement, of course, had not made these problems. Unfortunately, he did not know how to solve them, either. He was not a soldier like old Julius. He lacked his uncle‘s ability to judge and deal with men. He was cautious when he might have been bold, dawdled when he should have acted and trusted allies whose promises were false.

Pope Clement was certain of only one thing — he was sick of being bullied by the Emperor Charles V. Charles treated him like an underling. He marched his Spanish troops through Italy whenever he pleased, demanding that Clement pay them with money from the papal treasury. This, Charles said, was in accord with the treaty he had signed with Pope Leo and Clement was powerless to object. To thwart the emperor, the pope conspired with the king of France, who promised to send a mammoth army into Italy. With a sudden show of courage, Clement cancelled his payments to the emperor, raised a small army of his own and urged the leaders of Italy to make ready to help the French liberators.

No French came. Instead, marching south from Lombardy, came a roaring, unruly troop of 20,000 Spanish and German toughs, the Imperial Army of Charles V. Without the pope’s gold, Charles could not afford to hire a regular army, so be had recruited men who were willing to fight for the sake of the loot they could steal from captured cities. Ragged, unpaid and starving, they tramped down the peninsula to Rome. For two weeks they sat in the meadow outside the city, sniffing the tempting odors of the cooking-fires inside and catching, too, or so it seemed, the heady smell of riches. Then they crashed through the walls and poured into Rome.

The pope’s little army of 4,000 was no match for this mob of ruffians, who fought for food as well as gold. Clement himself barely escaped the attackers. As they broke into his palace, he dashed away and scrambled into the Castel Sant’Angelo, Pope Alexander’s fortress. There he paced the walls, directed cannon fire and helplessly watched the destruction and slaughter in the city below.

THE SACK OF ROME

Never in 2,000 years of wars and violence had the Romans suffered such cruelty or known such terror. The barbarians, the destroyers of ancient Rome, were not as fierce as these hungry invaders who roamed the streets like furious animals set loose from their cages. They killed without reason — women as well as men, the patients in a hospital, the people who sought refuge in the churches. They broke into every house in the city, took what they could find and howled for more. “Your money or your life,” was their cry, and those who had nothing to pay were tortured or killed.

Many of the German soldiers were followers of Luther. To them the pope and his officers were thieves, villains who taught a false religion and the soldiers took special care to rob the church and the monasteries. They stole the candlesticks and crosses from the altars and sacred relics from the papal palace. When they caught a cardinal or bishop, they stripped off his robes and made him perform frantic dances while they slashed at his ankles with their swords.

For days, the Romans hid in the ruins of the city. At night the sky reflected the glow of burning buildings and the smoke-filled streets echoed with cries and the tramp of the warriors’ boots. Then Pope Clement surrendered, agreed to remain a prisoner in Castel Sant’ Angelo until the emperor sent him permission to come out and the time of terror came to an end.

The pope stayed in his castle-prison for seven months. He wandered about the useless fortifications and spent hours locked in a dark, silent room, mourning his lost honor and the anguish he had brought on his people. Messengers from Florence brought news of a new defeat: the Florentines had once again driven the Medici out of their city. The pope added this to his list of sorrows and went on with his pacing and his mourning, When at last the emperor told him he was free to go where he liked, Clement disguised himself as a servant, slipped out of Rome and hid himself in an old castle in the country.

Meanwhile, nature had dealt a kind of justice to the warriors who had treated Rome so cruelly. Weakened by months of campaigning without proper food, they were easy victims for the sicknesses that bred in the steamy swamps that lay about the city. Ten thousand of them died of the plague.

Now French troops poured into Italy — two years too late. As they swept victoriously down the peninsula, Clement’s spirits rose but at Naples, the Frenchmen, like the Spaniards and Germans, were struck down by plague and disease. The French king made his peace with Charles V and the pope, his last hope gone, swallowed the little pride he still had and humbly begged for terms.

The emperor was generous. Clement had to admit the power of Spain in Italy and promise that he himself would place the emperor’s crown on Charles’ head. Charles agreed to allow the pope to rule the States of the Church and promised to return the Medici to power in Florence. In June, 1529, the treaty was signed at Barcelona in Spain. Then Charles journeyed to Italy to receive his crown and the forgiveness and blessing which the pope was forced to grant him.

The emperor’s coronation was as magnificent as money and power could make it, but it was rather spoiled by one unfortunate detail — Charles had not yet handed over Florence to the pope. The Florentines, deciding to put up a fight, had hired Michelangelo to design new fortifications for the city. He had done his job so well that Charles’ troops had not been able to break through. Charles, the ruler of most of Europe, could only have the city surrounded, cut off its food supply and wait. Eventually, of course, Florence had to give in. In July, 1531, the emperor placed the city under the rule of Clement’s twenty-one-year-old nephew, Alessandro, a budding tyrant who never pretended to abide by the old laws. Alessandro soon had the title of duke and he ruled like a duke. The triumph of the Medici — Pope Clement’s triumph — was complete.

That was Clement’s only triumph. When he died, in 1554, the Italians — churchmen, statesmen and soldiers alike — rejoiced that he was gone at last. It did not occur to them that they had all helped to bring about the disasters that had come to them. The foreigners had triumphed because the Italians had never given up their private quarrels, never joined together to defend their peninsula. The Church was divided because too many churchmen cared more about riches than religion, but it was easier to blame the pope.

In the years after Clement’s death, the Italians tried to regain the glory they had lost. Merchants again earned fortunes, cities flourished and Rome was built anew. The Church at last began a program of reform and the pope once more became a man of honour and esteem. But Italy no longer lived at the dawn of a new day or a new age. Its people were weary. Its scholars were content to pour over their old books in the quiet of their studies. Its artists turned away from the truth and strength of nature to more imaginary things, things that were pretty, unusual and soft. Many of the finest painters and sculptors left Rome and the other old centres of art. Some followed Leonardo to France. Many more went to Venice, the last great independent state of Italy.

MICHELANGELO

One artist, however, went on as before. Michelangelo, old and bad-tempered, still fought his lonely battle with the art that always demanded more of him. He had become a legend in Rome. People pointed him out to sightseers when he passed along the street — a fierce, broad-shouldered old man with a great, gray head and a sad face marked by the flat, broken nose. He wore old clothes, because he saw no reason to buy new ones and he wore them to bed, sometimes even the boots. “He had no mind to undress,” one of his friends explained, “merely that he might have to dress again.” He had, in fact, no mind for anything but his work.

Years passed. Popes were elected, died and new popes took their places. Michelangelo worked for those who would have him and ignored those who would not. When there was no work for him in Rome, he went to Florence and carved statues for the Medici tombs, monuments which Pope Clement paid for in his will.

In 1546, when the artist was seventy-two years old, Pope Paul III asked him to take charge of the work on St. Peter’s Basilica. As always, Michelangelo objected; he was a sculptor, not an architect. As always, he finally agreed to do the job. For eleven years he worked at new designs for the great church. He was haunted by the fear that he would not live to finish them. “I am so old,” he said, “that Death often pulls me by the cape and bids me go with him.”

At eighty-three, he made the clay model of a dome for St. Peter’s, a dome of vast width whose weight would be immense. Many architects questioned whether it would stand up at all. In 1588 it was completed and it stood firm, an architectural triumph to match Michelangelo’s triumphs in sculpture and painting.

Michelangelo did not live to see the dome rise above St. Peter’s and Rome. He died in 1564, leaving his “soul to God, his body to earth, and his goods to his nearest relations.” He died sorrowing for the things he had not done, for Julius’ monument, which had not been built; for St. Peter’s, which was barely begun; for the Medici tombs, only two of which had been carved. These tombs were his last great project and something of a puzzle to everyone who saw them. For on one he had carved the curious, perplexing figures that have come to be called “Day” and “Night”– a man looking out at the world in wide-awake fear and a sleeping woman who lies beside a frowning mask, a reminder of her troubled dreams. When Michelangelo was asked what these strange figures meant, he answered only, “Time, which consumes all things.”

Michelangelo had indeed watched time consume Italy. He had known the Golden Age of Florence. He had seen the splendours of Rome in the time of Julius and Leo; he had lived to see those days of greatness end. The invaders came, courage and independence fled and the spirit of the age that men would call the Renaissance moved on to other countries.