Pierre watched the merchant caravan clatter down the narrow dirt road that led through the manor. Pack mules threaded their way to avoid the deep puddles, while the horses strained as they pulled the creaking two wheeled carts. Pierre envied the merchants as well as the sturdy bowmen who guarded the caravan. During his seventeen years Pierre had never been more than a few miles from the manor where he had been born a serf. He was not free to move around as were these merchants who were city folk. Was it true, as Pierre had heard, that a serf who escaped to a town or city and lived there for a year and a day was forever free? He wondered. The merchant caravan disappeared around the bend in the road. Should Pierre follow it? To stay on the manor meant a serf’s life — a life of back-breaking toil. That night after dark, his mind made up, Pierre slipped unseen across the fields and onto a narrow path that led over the surrounding hills. For two nights he walked as rapidly as he could, sleeping fitfully in deep thickets during the daylight hours. Soon after sunrise on the second morning the forest trail led to a wider road, an hour’s journey out of the city of Lacourt. Pierre helped to free an oxcart bogged down in the mire of the roadside ditch and then trudged toward Lacourt in the company of the grateful driver. The young serf’s eyes grew wide with wonder at the unfamiliar sights as he approached the outskirts of the city. Completely encircling it was a wall of stone four times the height of a man. At one point the wall was pierced by a gateway, its great oaken doors swung back. Through the opening Pierre could …

Read More »The Counter Reformation 1521-1648

THE BLAST OF MUSKETS and the clang of swords against armour echoed across the plains of Italy, Spain and the Lowlands. Warriors of the king of France were clashing with the Spanish infantry and German knights of the Holy Roman Emperor. Control of the nations of Europe was the prize both nations sought. They schemed and plotted; their generals planned campaigns; their soldiers marched out to victory or defeat. Victories counted for little, for much of Europe’s future was decided by another, different kind of war – a war for the minds and souls of men. Village squares and royal council chambers, churches, university lecture halls and schoolrooms were the battlefields of this new war. Its troops were armies of preachers whose battle-songs were hymns and whose weapons were Bibles and textbooks. Reformers were on the march, Lutherans and Calvinists. Their thundering voices shook the domes of ancient cathedrals and wakened bishops dozing in their palaces. The Reformers won no easy victories‚ however. The forces of the pope were also on the march and the strongholds of the Church were well defended. Frightened by rebellions in Germany and Switzerland, the Catholic leaders in Rome took further measures to strengthen the Church. “There is but one way to silence the Protestants’ complaints‚” a learned churchman told the pope “and that is not to deserve them.” Lowly monks and the powerful cardinals alike began to talk of reform, of hard work, of honesty and godliness. Gradually there were deeds to match the talk — a great Church house-cleaning that one day would be called the Counter-Reformation. Meanwhile, in Europe’s towns and colleges‚ new soldiers of the Church appeared. Their uniforms were the simple black robes of monks, but their minds were as keen as dueling swords — much too sharp and smooth, …

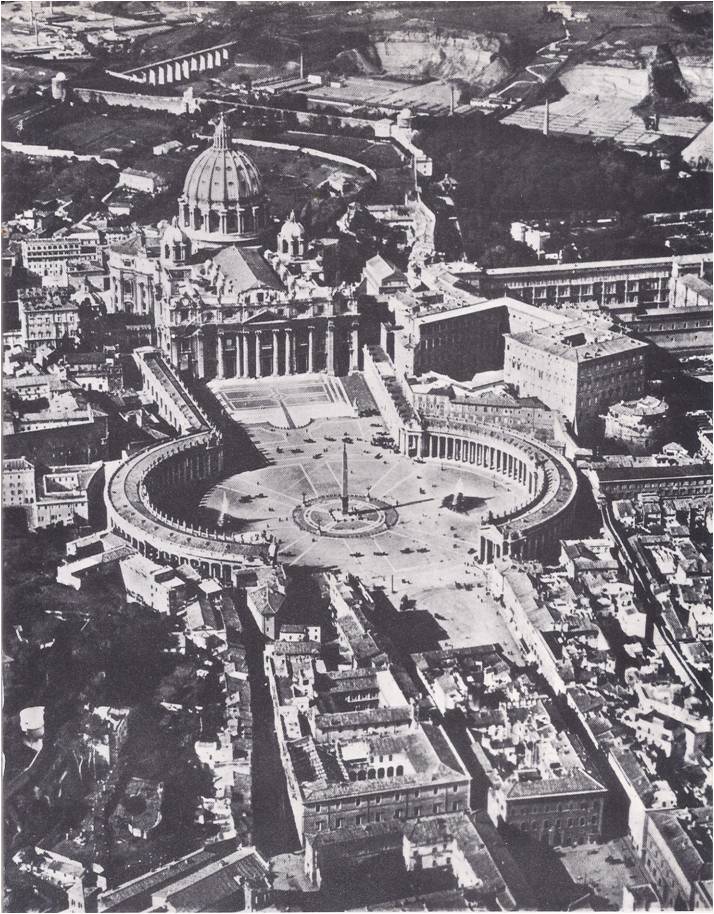

Read More »Rome, the City of the Pope 1492-1564

In 1492, young Giovanni de’ Medici bade farewell to his father, Lorenzo the Magnificent and left Florence to take his place in Rome among the cardinals of the church. At sixteen, Giovanni was a nobleman in the court of the pope, a man of influence and power. That was fortunate, for when Giovanni was eighteen, his family’s power collapsed. The Florentines drove the Medici from their city and Giovanni, who had come home for a visit, narrowly escaped being stoned by the citizens who once had cheered him. As he crept out of the city, disguised as a poor friar, he swore that he would one day return in triumph. First, he thought, he must look to his career in the church. Whatever the Florentines did, he was still a cardinal and in the papal court there were many ways for a clever man to rise to greatness. When he had crossed the Tuscan border, Giovanni threw off his humble disguise, put on the crimson robes and red hat that marked him as a “prince of the church” and took the road that led to Rome. The young cardinal was not alone in hoping to make his fortune in Rome. Indeed, the old city teemed with ambitious men of every sort — scholars and scoundrels, diplomats and spies, millionaires and fortune-hunters, priests and professional murderers. Rome had known every sort of splendour and evil. Memories of unmatched elegance and unbelievable cruelty lingered in the ruins of temples and arenas built by ancient emperors. Grim fortress-houses were reminders of an age of violence, when the bloody feuds of rival clans of nobles had turned Rome into a ghost city. Now there were new mansions, palaces and lofty churches. A new magnificence had come to Rome with the gold that poured into …

Read More »Gentlemen, Scholars and Princes 1400 – 1507

One day in the fifteenth century, the Turkish potentate of Babylonia decided to send gifts to the greatest ruler in Italy. He consulted his counselors and men who had traveled widely in Europe, asking them who best deserved this honour. They agreed that one Italian court outshone the rest and that his court must surely be the home of Italy’s mightiest sovereign. They did not name Milan, the home of the proud Sforza, nor Florence, the city of the clever Medici. The most magnificent court in Italy, they said, was at Ferrara, the capital of the dukes whose family name was d’Este and to Ferrara the Turkish potentate’s ambassadors carried the presents. Ferrara was small, a mere toy state in comparison to Milan or Florence. Actually, it was not an independent state at all. Like several of its neighbours in central Italy, Ferrara had for centuries belonged to the Church. Its duke paid an annual tribute to the pope for the privilege of governing his family dukedom himself. Even so, the Turkish potentate’s advisers had made no mistake. No court in Italy could match the splendor of the court commanded by the dukes of little Ferrara. During the Renaissance, there were many such small cities that won fame. It all depended on their rulers — the ambitious dukes or counts or sometimes, commoners who had gained riches and power. With their money, they, too, hired fine artists, sculptors and architects; they, too, collected manuscripts and things of beauty. So the small cities were as much part of the new age as Florence or Milan. In that new age, Ferrara was a place of old fashioned grandeur. Its dukes, the d’Estes, had come to power in the last days of chivalry. In 200 years, the d’Estes had turned Ferrara into a …

Read More »