IN 1415, WHEN ALL OF CHRISTENDOM belonged to one church and Christians battled pagan Turks instead of one another, a force of Portuguese marines set sail for the coast of Africa. They planned to attack a town called Ceuta. A stronghold that guarded the narrow passage connecting the Mediterranean Sea with the Atlantic, Ceuta was the end link in the chain of fortresses and well-armed ports that the Turks had tightened around the southern and eastern boundaries of Europe. Held in by this chain, European merchants could not trade in the luxury-filled markets of the east, pilgrims could not journey to Jerusalem and missionaries could not carry the word of God to the countless “lost souls” of Africa and the Indies. While the Turks held Ceuta, it was dangerous for the merchants of northern and southern Europe merely to trade with one another. So the king of Portugal sent out an expedition of his toughest marines. At their head he placed his own son, Prince Henry, who was young but skilled in the tactics of war. With a favourable wind driving his ships at top speed, Prince Henry caught the Turks by surprise. He sank their fleet, destroyed their docks‚ burned their town and triumphantly sailed home to announce that the sea routes were free once more. The king rewarded his son by naming him master of the Naval Arsenal at Sagres, the port of Lagos and all of the Cape of St. Vincent, the rocky headland that jutted like a pointing finger from southern Portugal into the Atlantic. Prince Henry was delighted. Ships and the sea were his love and his life and he had many ideas for the fleet that now was his to command. These ideas were the beginning of a great age of exploration. They would …

Read More »Japan’s Change and Slow Growth A.D. 838-1150

BETWEEN THE ninth and twelfth centuries, Japan developed at a slower pace. It was as if the people knew that they needed time to digest what they had learned. After 838, the government sent no more official missions to China. The Japanese continued to value Chinese civilization as highly as ever, but they went about things in their own way. Slowly, Japan became thoroughly Japanese. Prince Shotoku’s dream of a strong central government had come true. In time, however, the same evils that plagued Chinese dynasties in their later stages began to plague Japan. Thanks to their high positions at court, the noble landowners did not have to pay taxes. As a result, they grew richer and were able to buy more land. Although more Japanese land was being farmed all the time, less and less of it could be taxed. The government’s income fell while its expenses rose. Naturally, the government tried to make the landowners pay taxes. This move was bound to fail, for the officials who were supposed to carry out the order were the very men who profited most from not having to pay taxes. It was like asking them to pick their own pockets. Failing in this attempt, the government raised the taxes of landowning peasants instead. To escape paying these taxes, some peasants put themselves under the protection of the nearest great landowners, while the more adventurous headed north for the thinly settled Ainu country of North Honshu. Either way, their taxes were lost to the government, which became weaker and weaker. In China, a foreign invader or a rebel leader would have overthrown the sickly government and made himself ruler. In Japan, nothing of the sort happened. For one thing, there was no enemy at Japan’s borders, only miles and miles of empty …

Read More »Japan, the “Source of the Sun” 3000 B.C.-A.D. 400

THE Japanese islands — four large ones and many smaller ones — rise out of the Pacific Ocean to the east of China and Korea. They form a bow that bends from southwest to north for eleven hundred miles. The northern tip is at the same latitude as Montreal and the southern tip at that of Florida. Long ago, the people of the islands noticed that the sun always seemed to rise out of the ocean. They named their land Nihon or Nippon, “the source of the sun.” To the Chinese, on the mainland of Asia, the sun often appeared to rise from the direction of the islands. So they, too, called the islands “the source of the sun.” In their language, this was jih-pen. While the islanders continued to call their country Nippon, people in other parts of the world borrowed the Chinese name and called it Japan. Altogether, Japan is no bigger in area than Montana. It is so mountainous that only about a fifth of it can be farmed. Where the land is not too steep or rocky for farming, the soil is poor. Japan is fortunate in its climate. The southwestern part of the country has such a long growing season that farmers can raise two crops a year. Their main crop is rice, which yields more food per acre than almost any other food crop. The waters around Japan are full of fish. This is why Japan has been able to support a large number of people, even though it has so few natural advantages. The Japanese belong to the same Mongoloid race as the Koreans, Manchurians, Mongolians and Chinese. They are shorter and often darker-skinned than their neighbors and their men grow beards more easily. Because of their smaller bodies, some scientists believe that …

Read More »The Ming Dynasty Restores the Old Order A.D. 1368-1644

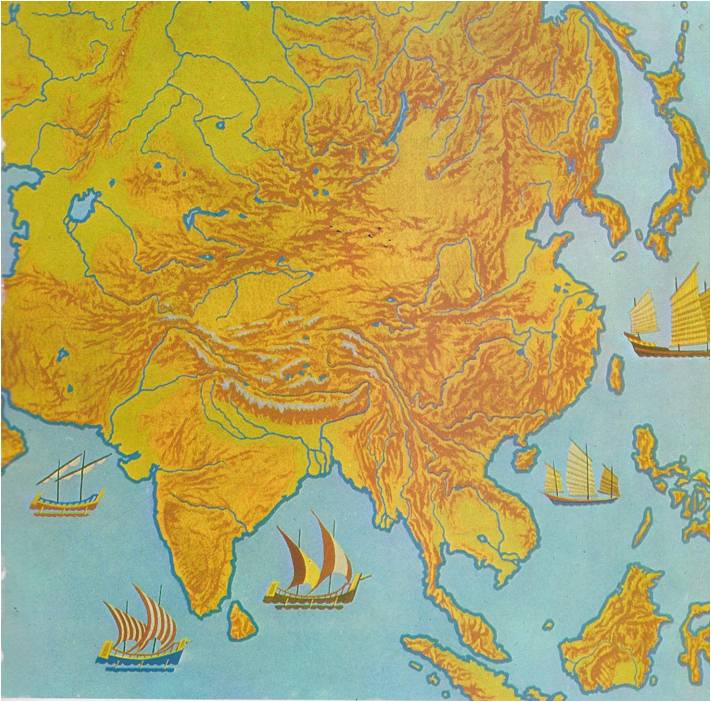

THE MEN who took over from the Mongols came to be known as Hung-wu, or “Vast Military Power.” Hung-wu named his dynasty ming, or “brilliant.” As things turned out, however, the Ming dynasty was not particularly brilliant. It was, in fact, humdrum compared to the Han, the T’ang, or even the Sung. Nevertheless, it gave China nearly three centuries of order, from 1368 to 1644. Hung-wu was born in a hut near Nanking in 1328. His parents soon died and the boy entered a Buddhist monastery, where he learned to read and write. His studies completed, he went out into the streets and begged for a living. Then, at twenty-five, he joined a band of rebels. Through character, intelligence and energy, he became its leader. In 1356, he captured Nanking from the Mongols and then, little by little, occupied the entire Yangtze Valley. In 1368 at the age of forty, he seized Peking and proclaimed himself emperor. THE TRIBUTE SYSTEM Hung-wu chose Nanking as his capital. At first he ruled through government departrnents, but as time went on he treated his ministers more and more contemptuously. In 1 375, he had one of them publicly beaten to death with bamboo sticks. Five years later, suspecting his prime minister of plotting against him, he abolished the office and took all state business into his own hands. The older he grew, the more distrustful he became. Fat and pig-like, with tufts of hair growing out of his ears and nostrils, Hung-wu was a sad and lonely man all his life. His personality was so commanding and his achievements so vast that after he died in 1398 nobody could forget him. His successors tried to copy his one-man government. Like him, they had officials who displeased them beaten, tortured and killed. Next to …

Read More »The Sung Dynasty: Barbarians Threaten the Empire A. D. 960 – 1279

DURING THE turbulent Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms era, the main outside threat to China came, as usual, from the north. A tough Mongol people from Manchuria helped one of the Chinese Warlords conquer North China. In return, he let them settle around Peking. Some of them became farmers, but their nomadic habits of roving and fighting remained strong. From time to time they raided the North China Plain, striking terror into the hearts of the peasants. These troublesome people were called the Khitan. Another form of their name, Khitai, sounded like “Cathay” to European travelers who later came to China. Throughout the Middle Ages, China was known in Europe as Cathay. In 960, the ruler of north China sent his best general after the Khitan to teach them a lesson. Instead, the general seized power and proclaimed himself emperor. As founder of the Sung dynasty, he was later called T’ai Tsu, or “Great Beginner.” Before he died in 976, he conquered most of China. His brother T’ai Tsung — “Great Ancestor”– conquered the rest, except for the Khitan kingdom in the northeast. The Sung dynasty was to reign until 1279. A1though it started out boldly, it never became as powerful as the Han and T’ang dynasties. One reason was that the emperors deliberately kept their army commanders short of men and money to make sure they did not revolt. As a result, the empire was constantly menaced by barbarians. In the end, it was destroyed by them. For generations, the Sung emperors bought peace by bribing the Khitan and a northwestern barbarian nation called the Hsi Hsia. Then a third barbarian nation entered the picture. In 1114, Manchurian nomads who called themselves the Chin, meaning “Golden,” attacked the Khitan. Seeing a chance to recover the long-lost northeast territory, Emperor …

Read More »The Six Dynasties: Turmoil and Change A.D. 220-589

THE three states into which China had split were soon split up themselves into even smaller divisions. For three and a half centuries, war raged almost continuously among rival kings. Doubt and confusion were everywhere. The period between 220 and 589 is called the Six Dynasties era, after six ruling families in a row which used Nanking as their capital. In all those years‚ the memory of the Han Empire never died. Looking back longingly at the peace and order of that time, the people came to think of the Han government as the great model which all rulers should try to copy. With the country divided, it was easy for the barbarians to invade. During the fourth century, wave after wave of nomads rolled south across the North China Plain, as the Huns were joined by their relatives, the Mongols and the Turks. Riding swift ponies, the invaders mowed down the Chinese foot soldiers with deadly arrows from their crossbows. Huge numbers of Chinese fled-some to Kansu in the northwest and Szechwan in the west, but many more to the lands south of the Yangtze River. The Chinese population of south China doubled, tripled and quadrupled, until it overwhelmed the non-Chinese population. Even in north China the Chinese greatly outnumbered their barbarian conquerors. Due to this and because the Chinese system of government was much better suited than theirs to a country of farmers, the newcomers gradually adopted Chinese ways. THE SEVEN SAGES Chinese ways were themselves changing. Just as the rebellions, wars and invasions uprooted millions of people from their settled lives on the land, so they uprooted the beliefs by which these people lived. These beliefs, Confucianism and Taoism, were mainly rules for everyday living. They had worked well enough in orderly Han times, but they no …

Read More »China under the Han 206 B. C. – A. D. 221

THE vast East Asian land of China is named after its first family of emperors, the Ch’in. The Ch’in brought the country together under one government and built the Great Wall to keep out northern barbarians. They were in such a hurry to get things done, however, that they drove their subjects too hard and lost their support. In 206 B.C., after only a few years in power, they were overthrown. The Ch’in were replaced by an imperial family named Han. The Han dynasty ruled for two centuries before the time of Christ and then, after a break, for another two centuries. These two periods are called the Former Han and the Later Han. By the time the Han finally fell from power, the Chinese people all spoke the same language and used the same “idea-pictures,” made with brush-strokes, in writing. They had truly become a nation. To this day their descendants call themselves “men of Han.” The Former Han emperors took power away from rich landowners and gave it to officials who had passed difficult examinations in the teachings of Confucius, the great Chinese thinker and religious teacher. Their armies checked many attacks by wild herdsmen-warriors known as the Hsiung Nu, or Huns. As trade flourished, so did the painting of pictures, the composing of poems and the study of the classic Chinese writings of the past. Toward the end of their reign, however, the Former Han emperors had to surrender more and more power to the wealthy noblemen who owned the country’s richest farmlands. In A.D.8, a man named Wang Mang seized control of the empire. Although he was a nobleman himself, he set out to reform the unfair tax system which allowed aristocratic landowners to grow rich at the expense of the peasants and the government. He …

Read More »India: A Thousand Years of History A. D. 1 – 710

UNTIL 1947, when the Moslem state of Pakistan was carved out of its western and eastern corners, the entire triangle of land that points south from the Himalaya Mountains into the Indian Ocean was known as India. Geographers call this huge land mass a subcontinent, because it is almost completely cut off from the rest of the continent of Asia. The Himalayas on its northern frontier form a continuous barrier of rock, the highest in the world. “MOTHER GANGES” From the southern slopes of the Himalayas, two great rivers run down to the ocean. The valley of the Indus River, on the west, is mainly desert; overlooking it are the only breaks in the Himalayan wall, the Khyber Pass and the Bolan Pass. The valley of the Ganges River, on the east, is a broad, fertile plain. Indians consider this river holy and call it “Mother Ganges.” Together, the Indus and Ganges Valleys make up North India. South of the Ganges Plain rise the Vindhya Mountains. To the south stretches a very large region of hilly uplands, called the Deccan. At its western and eastern edges the Deccan drops suddenly to coastal plains, forming long mountain walls called Ghats. The Vindhyas, the Deccan, the Ghats and the strips of lowland along the coasts make up South India. INVADERS FROM THE NORTH Geography influences history. This is particularly true of India — so much so, in fact, that North and South India have really had two separate histories. From earliest times, the people in both parts of the country were mostly poor farmers, living in villages. They shared the beliefs of the Hindu religion. Hinduism taught them that life was only a dream, they paid little attention, north or south, to the events that took place in their lifetimes. Otherwise, however, …

Read More »The Abbasids: Glory and Decay 750 -1258 A. D.

UNDER THE Omayyads, who ruled from 661 to 750, Islam had grown into a mighty empire. Arabic had become its language, while the Arabs, in turn, had picked up useful skills from the peoples they had conquered. The state had grown rich from the tribute paid by non-Moslems and the land tax paid by landowners. Though the caliphs were mainly concerned with pleasure and power, they had not neglected religion completely. They had built the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem and the Omayyad Mosque in Damascus — two magnificent sanctuaries which were the holiest places in Islam after the Kaaba and the Medina mosque. The believers had become divided, as they would remain divided, into Sunnites and Shiites. Now it was the turn of the Abbasids, who were to rule over the eastern part of the Arab Empire from 750 to 1258. Their first century of power was the Golden Age of Islam. Of all thirty-seven Abbassid caliphs, three stand out above the rest: al-Mansur, Harun al-Raschid and al-Mamun. Although he reigned after his brother the Bloodshedder, al-Mansur (754-775) was the real founder of the dynasty. It was he who firmly established it in power. He crushed a rebellion of Shiites. He raided the border strongholds of the Byzantines. He appointed the first vizier, or chief advisor. This practice, copied from the courts of the Persian emperors, was carried on by all the caliphs who came after him. BAGHDAD AND ITS RULERS Al-Mansur’s greatest achievement was building Baghdad, the fabled city of The Arabian Nights. He himself chose the site on the banks of the Tigris. Constructed in four years by a hundred thousand architects and workmen, Baghdad became the imperial capital of the Abbasids. It also became one of the greatest centres of trade in the world. To …

Read More »The Land of the Great Wall 4000 B.C. to A.D. 220

For many generations, the ancestors of P’an Keng had considered themselves kings in northern China. Yet this family of kings, the Shang Dynasty, had never governed from a central capital. About 1380 B. C., P’an Keng decided it was time to set up a capital. He found what seemed to be the perfect site at Anyang. Situated near a bend in China’s Yellow River, the fertile plains were ideal for farming and pasture, while the mountains behind it had timber and wild game. Only one thing remained: P’an Keng had to find out if the move was approved by the gods and his ancestors. P’an Keng sent for a diviner, one of the wise men who could read the will of the spirits. Everyone consulted the diviners for help in making decisions, whether it was the king planning a battle or a farmer wanting to know when to plant. Usually the diviner used animal bones in which small oval pits had been drilled. The diviner would heat a bronze rod in a fire and touch its point to the side of a pit. The heat cracked the bone slightly and by examining the size and angles of the cracks, the diviner interpreted the message of the spirits. For special occasions in China, the diviner used a large piece of tortoise shell in place of bones and the choice of the capital was such an occasion. P’an Keng began to ask his questions, “should the capital be set up at Anyang?” “Was the dream a good sign?” “Does Shang Ti, the great god approve?” “Will Tang, founder of the Shang Dynasty, aid this move?” P’an Keng was overjoyed to hear the diviner interpret the answer to each question as “Yes” or “Fortunate”. This meant that the spirits approved. Since this was …

Read More »