VETERANS or the Union Army, returning to their home towns in New England or the Middle Atlantic states after the war were surprised at what they saw. They had grown up in towns where most of the people lived by farming, while the rest sold things to farmers or worked in local workshops. Perhaps a mill and a factory had stood on the bank of the town’s river. The farms, stores and workshops remained, but now there were many new brick buildings used for factories, mills and warehouses. American industry, concentrated in the river valleys and ocean ports of the northeast, had grown with a rush during the Civil War. Behind the fighting lines, factories had turned out rails and telegraph wires, rifles and bullets, boots, uniforms, blankets, tents — all the articles needed for the Union forces. These products of Northern industry made a big difference on the battlefields. Before the war, the South had been an agricultural land, with large plantations worked by slaves and smaller farms worked by poor white farmers. Cotton was the big crop and great quantities of it were sold, especially to the mills of Great Britain. The wealth of the South, based on the unpaid labour of slaves, had given it as much influence within the nation as the North, which was partly agricultural and partly industrial. The South had little industry. When war came, it was unable to keep its fighting men supplied with weapons and other needs. The ill-equipped Southerners were worn down by the well-equipped Northerners, until finally they were completely defeated. The victory of the Union upset the balance of power between the North and the South. With the freeing of the slaves, most of the Southern planters were ruined, while the leaders of industry in the North were …

Read More »The Road to Yorktown 1777 – 1781

The big English setter did not look like a stray dag. When it came wandering into Washington’s camp one day in the fall of 1777, a soldier brought it to his officer. The officer took it directly to Washington’s headquarters and pointed out the name on the dog’s collar–“General Howe.” Washington had the dog fed while he wrote a polite note to General Howe. Half an hour later, the dog and the note were sent to the British camp under a flag of truce. The incident was not important, but it gave the Americans something to laugh and joke about for several days. There had not been much cause for laughter in recent weeks. General Howe had taken Philadelphia, America’s capital and its largest city, after defeating Washington at Brandywine and at Germantown. Washington’s losses had been heavy. He was now camped in the hills of Valley Forge, some twenty miles from Philadelphia, in desperate need of supplies of all kinds. In the North, moving down from Montreal, General Burgoyne had captured the fort at Ticonderoga and had continued on to Fort Edwards on the Hudson. Burgoyne, however, was having his troubles, too. He was almost out of food and his supply base at Montreal lay 185 miles north, through almost trackless wilderness. Burgoyne knew that east of him there were large stores of food and many cattle at Bennington, in what is now Vermont. He sent out a detachment of 1,300 men to raid the place and to bring back all the cattle and horses they could find. The detachment marched into a trap which had been set for it by John Stark and his New England militia and when the short battle was over, the British had lost. American losses were thirty killed and forty wounded. The Indians …

Read More »The Final Break 1776

The fog was lifting over New York early on the morning of June 29, 1776, when a man named Daniel McCurtin happened to glance out over the bay. At first he saw nothing but mist hanging low over the water then suddenly he blinked and stared in amazement. Later he tried to describe the scene. He wrote that he had “spied as I peeped out the Bay something resembling a wood of pine trees trimmed. I declare, at my noticing this, that I could not believe my eyes, but keeping my eyes fixed at the very spot, judge you of my surprise when in about ten minutes, the whole Bay was full of shipping as ever it could be. I declare that I thought all London was afloat.” Washington’s lookouts on the share of Long Island were blinking, too, as General Howe’s mighty fleet of 130 ships arrived in the Lower Bay. This was the Army Howe had taken to Halifax after being forced out of Boston, but now it was greatly strengthened. The fleet anchored near Staten Island, shifting its anchorage in the bay several times during the next few days. The Americans waited, trying to guess where the attack would come. At Manhattan? Or Brooklyn? Or would Howe sail up the Hudson and attempt to join forces with a British army coming down from Canada by land? Howe finally put his army ashore on Staten Island at the month of the harbour, which was not defended. The British were not yet ready to strike. They were awaiting reinforcements from England. The delay gave Washington more time to fortify his positions in Manhattan and across the East River on Brooklyn Heights. To defend both places meant splitting his small army in half, with the East River between them. Had …

Read More »A Divided Country 1776

One chilly morning in April, General Howe stepped out of his Boston headquarters and stared in amazement at a hill called Dorchester Heights, to the south of the city. It had been fortified during the night by George Washington’s rebel army. Strong breastworks of ice blocks and brown earth ran along the crest of the bill. Above the steepest slopes, barrels filled with rocks stood balanced, ready to be sent tumbling down the hill in the path of attacking troops. Studying the hill through his glass, Howe could make out several companies of riflemen and some units with muskets. What disturbed him most were the cannon, all well placed on the top of the hill where they could pound Boston and a good part of the Royal Fleet in the harbour. None of the British cannon, from their low positions‚ could possibly place their shots farther than the bottom of the hill. Howe made ready to attack, then changed his mind, probably haunted by the horrors of Bunker Hill. The British began making preparations to withdraw from the city. For the redcoats, the act of leaving Boston must have seemed like an escape from a prison city. They had been hemmed in there for many months, overcrowded‚ short of food and fuel. The civilian population had increased steadily, for a constant flow of colonial refugees had poured into the city to seek the protection of the British army. These refugees supported the mother country and called themselves loyalists because of their loyalty to the king. During the winter they had caused serious food and housing problems and greatly endangered the health of all. WASHINGTON TAKES BOSTON It may have been one of the loyalists who carried smallpox into the city. The disease had spread rapidly and raged for several weeks. …

Read More »War Begins on Lexington Green 1775

On the evening of April 18, 1775, Paul Revere quietly made his way through the dark streets of Boston to the Charles River. At the river’s edge he hid in the shadows, watching and waiting. He kept a sharp lookout for British patrols. Spies had brought the patriots word that the British were to launch a surprise attack; Revere, William Dawes and other members of the Sons of Liberty had made careful plans to warn the countryside. There could be no doubt that something was about to happen. Several days earlier, eight hundred of the best troops stationed in Boston had been taken off regular duty to prepare for action of some sort. According to the spies, General Gage had become alarmed at the way the colonists in every village were drilling and gathering military supplies. He was particularly concerned about the large supply of ammunition that the colonists had stored at Concord, some twenty miles from Boston. He was anxious to arrest Samuel Adams and John Hancock, who were spending a few days in Lexington at the home of Reverend Jonas Clark. PAUL REVERE’S RIDE Now a number of British patrols had been sent out on the roads leading to Lexington and Concord, so the patriots were certain that their information was correct. The British intended to arrest Adams and Hancock in Lexington and then go on to destroy the ammunition at Concord. Which way would the British go? Boston was located on a peninsula, connected with the mainland by a narrow neck of land. The British might go over the neck‚ through Roxbury and Cambridge. That was the long way. They could cut off a number of miles by crossing the Charles River on boats. It was about ten o’clock when Paul Revere heard the sounds of marching …

Read More »Adventures in the New World 1519 – 1620

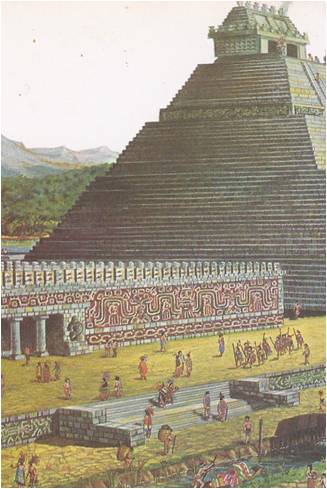

“I DID NOT come to till the soil like a peasant,” said Hernando Cortez. “I came to find gold.” His words echoed the thoughts of almost every Spaniard in the New World. The discovery of the sea route to the West had set off a great treasure hunt. Colonizing and slaughtering, building and plundering, the gold-hungry Spaniards won a Spanish Empire of the West. Conquistadores‚ they were called — the conquerors. None of the treasure-hunters was more cunning or ambitious than Hernando Cortez‚ who came to the island of Hispaniola in 1504. It was not until 1519 that the governor of Hispaniola sent him on an expedition to explore the coast of Central America. Cortez sailed with five ships, 500 soldiers, eleven cannon and fifteen horses. The fleet anchored near the coast of the territory called Mexico and the men went ashore to build a settlement. Cortez ordered the ships dismantled so that none of his men could go back to Hispaniola, then set off on a march inland. Mexico was a vast country whose Indians had built a highly organized civilization and Cortez had a force of less than 500 men. He was a skillful leader; besides, he had firearms and horses –and good luck. Not long after he began his march, a horde of Indians swept out of the hills to attack the Spaniards. As soon as the Spanish cavalry appeared, the Indians fled to safety. As one soldier later wrote, the Indians, “who had never before seen a horse, thought that steed and rider were one creature.” One tribe after another surrendered. They had been conquered by the people called the Aztecs and many of them offered to join Cortez in the fight to destroy the Aztec empire. As the Spaniards and their Indian allies pushed on …

Read More »