On the evening of April 18, 1775, Paul Revere quietly made his way through the dark streets of Boston to the Charles River. At the river’s edge he hid in the shadows, watching and waiting. He kept a sharp lookout for British patrols. Spies had brought the patriots word that the British were to launch a surprise attack; Revere, William Dawes and other members of the Sons of Liberty had made careful plans to warn the countryside.

There could be no doubt that something was about to happen. Several days earlier, eight hundred of the best troops stationed in Boston had been taken off regular duty to prepare for action of some sort. According to the spies, General Gage had become alarmed at the way the colonists in every village were drilling and gathering military supplies. He was particularly concerned about the large supply of ammunition that the colonists had stored at Concord, some twenty miles from Boston. He was anxious to arrest Samuel Adams and John Hancock, who were spending a few days in Lexington at the home of Reverend Jonas Clark.

PAUL REVERE’S RIDE

Now a number of British patrols had been sent out on the roads leading to Lexington and Concord, so the patriots were certain that their information was correct. The British intended to arrest Adams and Hancock in Lexington and then go on to destroy the ammunition at Concord. Which way would the British go? Boston was located on a peninsula, connected with the mainland by a narrow neck of land. The British might go over the neck‚ through Roxbury and Cambridge. That was the long way. They could cut off a number of miles by crossing the Charles River on boats.

It was about ten o’clock when Paul Revere heard the sounds of marching men. The British were on the move. He watched until he saw them take to the boats at Park Square. That was all he needed to know. He hurried to the North Church and told the man waiting there to hang two lanterns in the church tower, a signal to William Dawes and others that the British were going by water. Revere quickly returned to the waterfront, rowed across the river some distance from where the British were crossing and mounted a fast horse held ready for him on the other side. Meanwhile, Revere knew, William Dawes was riding the long way, through Cambridge. If one of them should get caught by a British patrol‚ the other might be able to get through and carry the alarm to Lexington and Concord. Other riders would fan out to alert the volunteer soldiers, called minutemen because they were ready to serve at a minute’s notice.

Revere set out at a gallop. “In Bedford,” he said later, “I awaked the captain and the minutemen and after that I alarmed almost every house till I got to Lexington.”

Just before dawn, he reached Lexington. The church bell sounded the warning that everyone had been expecting and farmers armed with flintlocks began gathering on the village green opposite the white Congregational Church. At Parson Clark’s house, Paul Revere reported to his friends Adams and Hancock. They were preparing to leave when Dawes came galloping up.

Revere and Dawes rode off together to warn the people of Concord. They had gone only a few miles when their way was suddenly blocked by a British patrol on horses. Dawes managed to slip by and continued on to Concord. Revere was caught, questioned and was forced to return to Lexington on foot.

By the time the first rays of sun flooded Lexington green, most of the farmers in the neighbourhood had gathered there, about seventy in all, under the command of Captain John Parker. From the distance came the music of fifes and drums. The music grew louder as the British marched into view over the crest of the hill on the road from Boston. The troops in the long column looked like toy soldiers, all in bright red and white, all marching briskly in perfect order. On they came, as if nothing could stop them, with Major Pitcairn riding ahead. Eight hundred experienced troops of the King’s army — what could less than a hundred untrained farmers with muskets hope to do against them?

“DISPERSE, YE REBELS!”

Captain Parker, who led the minutemen, seemed to be a little uncertain about it himself. He had been instructed to gather his men on the green, but no one had told him what to do next. “Let the troops pass,” he told his men.

As the redcoats came marching up, Major Pitcairn cried out, “Disperse, ye rebels! Lay down your arms and disperse!”

Captain Parker quickly ordered his minutemen to stay where they were. “Don’t fire unless fired upon; but if they mean to have war, let it begin here.”

For several moments nothing happened. Then a sharp report of a gun broke the stillness. No one ever knew who fired the shot, but it marked the beginning of the American Revolution.

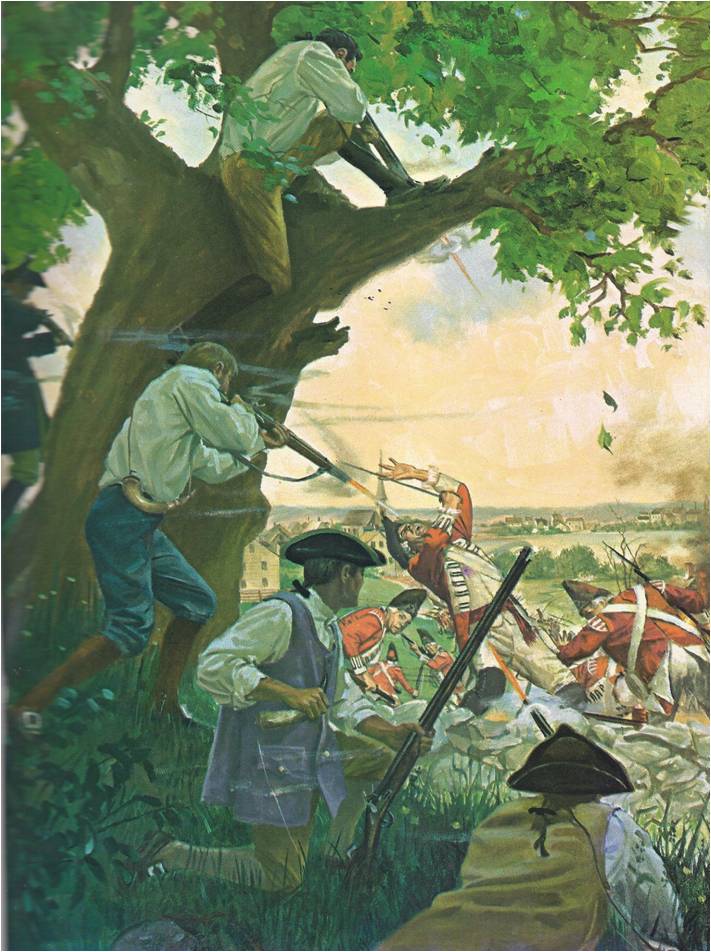

The redcoats, certain that the shot had come from the American ranks, replied with a hail of bullets. Major Pitcairn drew his sword and rode back and forth in front of his men, trying to make them stop firing, but they “were so wild they could hear no orders.” The patriots returned their fire, then scattered and took up positions behind houses, stone walls and trees.

Major Pitcairn finally regained control of his men. The shooting stopped. The smoke cleared from the green, revealing the bodies of eight dead minutemen, and several wounded. On the British side, one of the redcoats and a horse were slightly wounded.

BATTLE AT THE BRIDGE

The British set off for Concord without bothering to search the village for Adams and Hancock. They need not have been in a hurry. Most of the military supplies stored in Concord had already been removed by patriots and hidden in other places.

When the British arrived in Concord, they spent several hours in a house-to-house search of the village. They were polite and very proper in their conduct. At one house, an officer asked why the door to one of the rooms was locked. He was told that it was occupied by a sick person who wasn’t to be disturbed. He accepted this explanation and went away without knowing that the room was actually a storage place for military supplies. While the search was going on, three companies of light infantry stood guard at the North Bridge on the edge of town. Four other companies passed over the bridge to search the farm of Colonel Barrett a mile out of town.

All this time patriots from nearby villages were gathering in the hills beyond Concord. There was no one to take command. They talked things over and wondered what to do. A number of them formed a column of two’s and marched down the hill directly toward North Bridge. The British on the other side of the bridge opened fire. The minutemen scattered, took cover and aimed carefully. So deadly was their fire that the redcoats suddenly broke ranks and fled back to the village, leaving their dead and wounded behind.

The patriots had won the bridge, but did not know what to do with it and they went into the hills again to talk things over. They were still there, sometime later, when four companies of redcoats came marching back toward the bridge after searching the Barrett farm. Although the Americans probably outnumbered the redcoats by three to one, the British were allowed to pass without a shot being fired.

Many new units of minutemen joined the others in the hills during the morning hours. Some of the men had been up since dawn. Tired and hungry, they prepared to leave for their homes. They did not think of themselves as being at war. They had not come out to defeat an enemy in battle, but rather to prove to the British that they were prepared to fight for their rights. Those who were starting for home suddenly changed their minds when they saw a dark column of smoke rising from the town of Concord.

The British were merely burning some wooden gun carriages they had found, but the patriots did not know that. They thought the British were burning the entire village. Although they still had no plan of action, the angry minutemen lingered. At noon they saw the British marching toward Lexington. They followed behind, as if to make certain the redcoats were really leaving the countryside.

There was no shooting. The British might have returned safely to Boston had it not been for a little bridge over the Mill Brock. The narrow bridge acted as a bottleneck, slowing the British down. The rear guard became nervous. They suddenly wheeled and fired at the minutemen, probably trying to keep them at a safe distance.

To the angry minutemen the reports of the British rifles were like a command to open fire. They no longer had any reason for holding back. Closing in on both sides of the road and from the rear, they cut the tail end of the British army to bits in a deadly crossfire.

The patriots then swarmed over the brook to continue their attack from both sides of the road. They fought Indian style, firing at the marching redcoats from behind trees, rocks, houses and stone fences. The British light infantry units moved out on both sides to come up behind the Americans. This took some of the pressure off the main body of soldiers, but it was not enough. The road behind them was dotted with fallen redcoats. The column moved faster. As their ranks thinned out, the British began to show signs of panic. One of them, writing about it later, said, “when we arrived a mile from Lexington, our ammunition began to fail and . . . we began to run rather than retreat in order. . . .”

Some of them dropped their packs and rifles as they fled down the long slope into Lexington. They could not have gone on much longer, but in Lexington they were met by over a thousand fresh redcoats and several small cannon under the command of Major General Percy. Pitcairn’s men were so exhausted that they fell to the ground with “their tongues hanging from their mouths, like those of dogs after a chase.”

CAMPFIRES IN THE NIGHT

After a short rest on the village green, they set out for Boston. The rebels closed in once more and the running battle continued. By now the whole countryside was up in arms and new units of minutemen joined in the fight, more than making up for those who dropped out as they ran out of ammunition. The strain was too much for many of the British. They broke ranks, looted and burned houses along the road that served as snipers’ nests and shot at any civilian they saw. When their march ended in Boston late that night, they had lost seventy-two killed, 174 wounded and twenty-six missing. Losses on the colonial side were forty-three dead, forty-nine wounded and five missing.

The war had begun at last. In the hills and wooded areas surrounding Boston, the twinkling lights of hundreds of colonial campfires burned through the night. The campfires rapidly increased in number as patriots from all over New England gathered to keep the British hemmed in at Boston. The news of Lexington convinced many Americans that they would now have to fight for their liberty. The colonists begin making preparations for war in earnest. One newspaperman wrote, “Travel through whatever part of this country you will, you see the inhabitants training, making firelocks, casting mortars, shells and shot . . .” The most popular music, in Maryland was that of the fife and drum. It became fashionable in Virginia to carry tomahawks and to wear frontiersman’s hunting shirts.

THE GREEN MOUNTAIN BOYS

The Second Continental Congress met in Philadelphia on May 10, just three weeks after the battle at Lexington. The delegates were welcomed by smartly dressed companies of riflemen who guided them into the city. Most of the delegates were uneasy about the violence at Lexington. They still hoped something could be done to prevent war. So long as there was a chance to win back the liberty they had once enjoyed under the British Crown, they did not want to speak of independence. Benjamin Franklin went so far as to say, “I have never heard in any conversation from any person the least expression of a wish for independence. The Americans have too much love for their country.”

Many delegates feared that the fighting at Lexington would lead to other battles unless they acted quickly. They sent an appeal to King George, saying that they were still his loyal subjects. All they were asking him to do was to restore their liberties so that England and her American colonies could live in peace and harmony once again.

A few days later they learned that Ethan Allen and his militia from New Hampshire, known as the Green Mountain Boys, had captured the British Fort of Ticonderoga on Lake Champlain. Allen had taken the fort because its cannon and ammunition were badly needed by the army of New Englanders to drive the British out of Boston. The fort was considered important to the colonists for still another reason. It controlled the only inland waterway between the colonies and Canada.

The delegates were stunned by the news. The colonial victory had come at the very time they were appealing to the king for peace. Some suggested that the fort be returned to the British with an apology. Should they let the hot-headed New Englanders drag them all into war?

Questions of that kind troubled John Adams of Massachusetts. If the colonies were divided against each other, they would all be lost. He rose and told the Congress that England would undoubtedly strengthen her army in Boston. In time that army would become strong enough to defeat the colonial army surrounding the city. Where would it go, he asked, when it had crushed all resistance in New England? Yes, it would head southward, striking at other colonies one by one, for they were all guilty of resisting British authority.

Who could stop the British from sweeping over the land? None of the colonies had strength enough to do it alone, he warned, but together they could do it. He suggested that Congress set up a Grand American Army supported by all the colonies. Congress could start such an army by taking over the New England army now encamped on the outskirts of Boston.

Who would command the American army? John Adams confessed that he had been doing some thinking about that, too. The man he had in mind was “a gentleman whose skill as an officer, whose independent fortune, great talents and universal character would command the respect of America. . . That man was “a gentleman from Virginia who is among us here . . .”

GENERAL WASHINGTON

At this point, George Washington, who realized that Adams was about to mention his name, quietly arose and left the chamber.

Adams had still another reason for recommending Washington, which he told his friends in private. Washington came from the South. If the army had a commander from the South, it would help bind the colonies closer together.

Two days later, Washington was appointed “General and Commander-in-Chief of the forces raised and to be raised in the defense of American liberty.” He left Philadelphia almost at once to take command of the colonial army near Boston. Even then he had no thought of leading a fight for independence. “I am well satisfied that no such thing as independence is desired by any thinking man in all North America.” he wrote.

Congress began organizing the country for war, not with independence in mind, but to defend American liberty. It made plans to build a navy, to gain the friendship of the Indians, to print its own paper money and to establish a national postal system. In taking these steps, Congress was acting like the legislative body of a nation which had already won its freedom.