CHRISTIANITY, as the official religion of Byzantium‚ was under the control of the government. The emperor was the head of both church and state and high church officials in the East recognized him as the religious leader of the land. One of them wrote, “Nothing should happen in the Church against the command or will of the Emperor.” The church organization was similar to that of the state. As its head, but under the emperor, was the patriarch of Constantinople, who was appointed by the emperor. The appointment had to be approved by high church officials, but actually they never …

Read More »Tag Archives: Rome

Byzantine Glory A.D. 610-1057

The period from 610 to 717 was one of the darkest in Byzantine history. During that time, the edges of the empire crumbled under the pressure of powerful enemies. A people from northern Italy, the Lombards, conquered more than half of Italy. In central Arabia, the Arab tribes had joined together under the religion of Mohammed and marched against their neighbors. They took the kingdom of Persia, invaded Palestine and in 658 captured Jerusalem. The conquering Moslems, as the followers of Mohammed were called, swept on and soon took over Syria and Egypt. They marched along the northern shore of …

Read More »The New Capital: Constantinople A. D. 306-532

EMPEROR Constantine’s decision to build a new capital for the Roman Empire in the East did not come as a surprise to the people of the empire. Rome had lost much of its influence as the seat of government and emperors avoided the city. They preferred to build castles for themselves in distant provincial cities. Emperor Maximian, for example, had ruled from Milan. Emperor Diocletian had moved to Nicomedia, far to the east in Asia Minor and ruled from there. Constantine had many good reasons for turning eastward in searching for a site for his new capital. Most of the …

Read More »The Growing Church 100 – 500 A. D.

AT THE beginning of the second century, the Christian Church was a loosely organized group of independent local churches. There had been no strong leadership since the days of the apostles, no recognized authority to whom they could turn to settle their differences concerning the faith. Paul’s epistles had cleared up many points for them, but new questions were constantly arising. The Roman church had been taking a leading role for some time. There were a number of reasons for this. According to tradition, both Paul and Peter had died in Rome. It was the only church in the western …

Read More »Rome and the Christian Church A.D. 64 -180

TRUMPETS sounded the fire alarm in Rome on the night of July 18, in the year 64. It seemed that the flames first broke out in the crowded section near the Great Circus and spread rapidly, driven by a strong wind to row after row of wooden houses. Sparks carried by the wind started other fires. People fled in panic. The fire roared on unchecked, continuing for six days and six nights. When it was finally brought under control, most of the city lay in ruins. People could not believe that one small accidental fire somewhere could have caused all …

Read More »The Emperor’s City A. D. 14 to A. D. 117

GREAT power had allowed Augustus to do great good for Rome and its provinces. The same power in the hands of a man who was not good meant that he could do great harm. This the Romans learned as they watched the remarkable parade of good and evil men who came to govern Rome after Augustus. Some of them were wise, two or three were foolish, one thought he was the greatest artist in the world and another said he was a god. All were the masters of Rome, mighty princes who were called emperors. The title emperor came from …

Read More »The City of Augustus 29 B. C. – A. D. 14

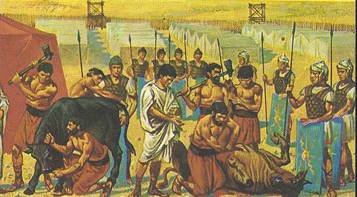

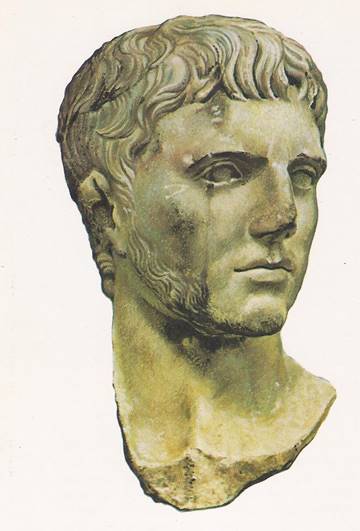

IN 29 B.C. the gates of war were closed. Rome was at peace. Senators and the people of the mob-men who had hated and fought each other through long, bitter years — stood side by side in the Forum while the great doors of the temple of Janus were slowly pushed shut. That had happened only twice before in the history of the city. The crowd in the Forum cheered the peace and they cheered Octavius, their new ruler. He was no longer the young man who had rushed to Rome after the murder of his uncle, Caesar. Seventeen years …

Read More »The Second Triumvirate 43 B. C. – 30 B. C.

AS THE news of Caesar’s death spread through Rome, sorrow, anger and fear took hold of the city. On March 17, two days after the murder, the Senate met again. Cassius, Brutus and the other assassins took their usual places. There was no doubt that most of their fellow senators felt that they had done the right thing in ridding Rome of a tyrant, but Caesar’ s veterans were still in the city, taking their orders now from Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, who had been his Master of the Horse, the commander of the cavalry. Mark Antony was still consul, he …

Read More »The City of Caesar 80 B. C. – 44 B. C.

THE story of Rome in the years after Sulla’s death was the story of a partnership of power. It was the tale of three men who bargained for the world — a rich man, a poor man and a man who was not only a hero, but looked it. The rich man was Crassus, who had become a millionaire by setting up the only fire department in Rome. The tall buildings and narrow, crowded streets of the city made a fire a constant danger. When one house burned to the ground, the buildings on either side were likely to fall …

Read More »The City Divided 130 B. C. – 70 B. C.

MARCUS TULLIUS CICERO, a young statesman known for his dramatic speeches, stood before a panel of judges in a courtroom in Rome. He stared at them angrily. For fifty days he had travelled through Sicily, collecting facts about the crimes committed by Caius Verres, the man who was on trial. Now the judges had told him that there would not be time to listen to his evidence. Cicero knew that the judges had been bribed. For it was no ordinary criminal that he meant to send to prison or to death. Caius Verres was an aristocrat and a senator and …

Read More »