Czechoslovakia was a country of many peoples. The largest groups were the Czechs and the Slovaks, but in the region called Sudetenland lived 3,000‚000 Germans. Although Sudetenland had never belonged to Germany — it had once been under the rule of Austria — Hitler was determined to “bring the Sudeten Germans home.” The Nazis had been active in Sudetenland for some time and after Hitler took over Austria they became busier than ever. Throughout the spring and summer of 1938, the Sudeten Germans made demands on the Czech government. In Germany, there were threatening troop movements. Hitler also began the …

Read More »Tag Archives: Switzerland

Totalitarianism Versus Democracy

AS THE 1930’s drew to a close, only eight countries in Europe, besides Great Britain and France, were still democracies. They were Belgium, Holland, Switzerland, Czechoslovakia, Norway, Sweden, Denmark and Finland. Three of Europe’s most important nations were dictatorships. The Soviet Union was communist; Germany and Italy were fascist. There had been dictatorships before, but these went further; they were totalitarian. The word “totalitarian” comes from the word “total,” and total control is what these dictatorships were after — total control of their people, total control of their actions and thought. There were differences between the totalitarian countries. While Stalin …

Read More »Stalemate in the West, Decision in the East 1914 -1917

Germany’s generals had for some time expected that they would have to fight both France and Russia, and Count Alfred von Schlieffen had devised a battle plan that took this into consideration. The Schlieffen Plan was a good one and it might well have brought the war to an early end — if General Helmut von Moltke, who succeeded Schlieffen as the German commander, had followed it. The plan called for the German army to be divided into an eastern force and a western force. Russia, vast and with few good roads or railroads, would need more time than France …

Read More »Democracy Spreads 1867-1905

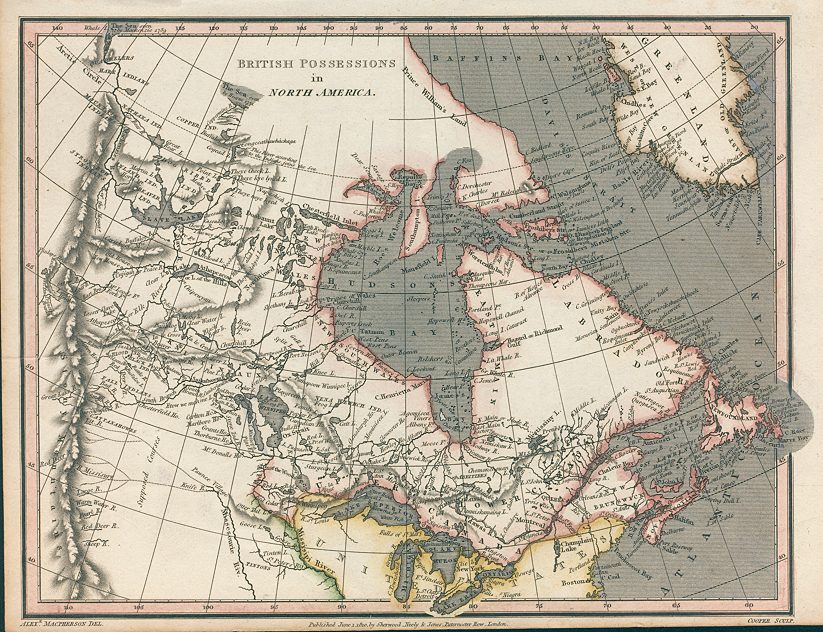

DEMOCRACY IN the Scandinavian countries, Belgium, Holland and Switzerland followed the pattern of the three large democracies. Everywhere during this period there was a trend toward constitutional government, elected law-making bodies, cabinet ministers with responsibility to the people, liberty, personal rights and voting rights for all men in the lower classes. In Canada, the most difficult problem was nationalism. At the time of the Civil War in the United States, Canada consisted of a number of British provinces, most of which were independent of each other. The oldest of these was the province of Quebec in the Saint Lawrence valley. …

Read More »Emperor of the French 1804 -1815

On December 2, 1804, in a ceremony of great pomp and splendour at the cathedral of Notre Dame in Paris, Napoleon Bonaparte was crowned Napoleon I, Emperor of the French. Pope Pius VII was there. He had come from Rome to offer his blessing and to place the crown on the head of the new emperor but Napoleon did not do what was expected of him. Instead of kneeling, he took the crown from the Pope’s hands and put it on himself. He also placed a crown on the head of his wife, Josephine. Only twelve years had passed since …

Read More »The Counter Reformation 1521-1648

THE BLAST OF MUSKETS and the clang of swords against armour echoed across the plains of Italy, Spain and the Lowlands. Warriors of the king of France were clashing with the Spanish infantry and German knights of the Holy Roman Emperor. Control of the nations of Europe was the prize both nations sought. They schemed and plotted; their generals planned campaigns; their soldiers marched out to victory or defeat. Victories counted for little, for much of Europe’s future was decided by another, different kind of war – a war for the minds and souls of men. Village squares and royal …

Read More »Preachers of Reform 1518-1564

IN 1518, AN INDULGENCE PEDDLER, a priest from France, made his way through one of the twisting Alpine passes that led into Switzerland. He carried with him a supply of bright banners, an impressive-looking copy of Pope Leo’s Declaration of Indulgences and of course, a collecting box. The French priest’s hopes were high, for the little Swiss merchant towns were rich. He did indeed do well at first and his collecting box began to grow heavy with pieces of gold. Then he came to the town of Zurich. As he began to set up his banners, a town official stopped …

Read More »The Monk from Wittenberg 1505-1546

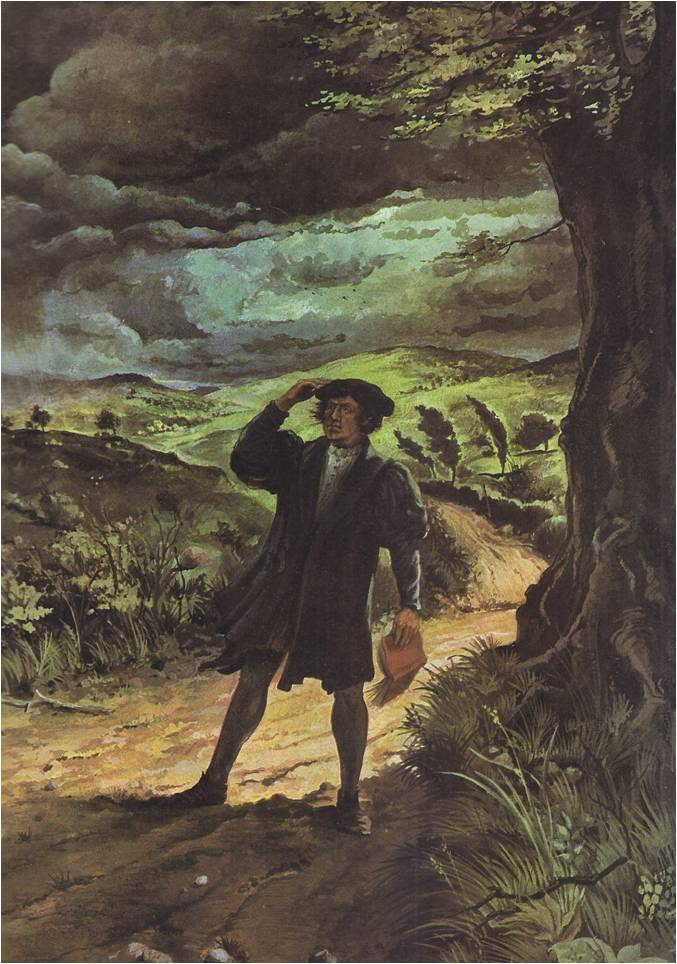

ON A SULTRY JULY DAY IN 1505, a young law student, Martin Luther, was walking along a country road in Germany when a summer storm blew up. The air grew heavy and black clouds filled the sky. Before Luther could take shelter, thunder began to crash. A bolt of lightning struck the road almost at his feet. Thrown to the ground, he lay shaking, not certain whether he was alive or dead. “Help me, Saint Anne,” he cried, “help me and I will become a monk.” After a moment, Luther’s trembling stopped. He stood up, found that he was not …

Read More »The End and the Beginning 378- 752

THE FIRST SIGN of the approaching Roman army was a thin column of dust. It rose like smoke from behind the jagged Thracian hills of Northern Greece, which sheltered the Visigoths’ encampment. Moments later, the Visigoths, or German barbarians, as the Romans called them, could feel the ground tremble with the tread of the imperial legions. The Romans were advancing, forty thousand strong, under the personal command of the Emperor Valens. Within the Visigoths’ barricade of wagons, all was confusion. Chieftains bellowed, calling their clans together. Sturdy Visigothic warriors dragged the wagons closer together in a protective circle. Horses neighed …

Read More »