As Roosevelt’s first term in office neared its end, many people in the United States — and in other countries — wondered if the New Deal could really solve America’s problems. More than that, they wondered if Americans would continue to follow the path of democracy. A wave of totalitarianism was sweeping the world; would it reach as far as America?

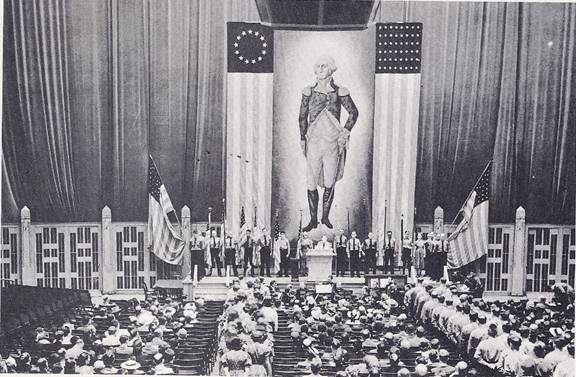

There was no doubt that there were some Americans who supported Hitler and the Nazis. Members of the German-American Bund paraded in brown shirts and held a mass meeting in New York’s Madison Square Garden, but there were comparatively few Bundists. Many people felt that a more serious threat to democracy and to the Roosevelt administration came from three native American political leaders — Huey P. Long, Father Charles E. Coughlin and Dr. Francis Townsend.

Most colourful of the three was Huey Long, a senator from Louisiana. Calling himself the Kingfish, he had come to power in his native state and he ran it, his critics said, as a dictatorship. He was a rousing orator and in front of a crowd he would spout folksy humour, crack sharp political jokes and play the simple country boy. His opponents, however, charged that he was a combination of brutal hoodlum and a shrewd political boss who would stop at nothing to get what he wanted. He would promise the people anything — and he did keep some of his promise. He saw that Louisiana got better roads, schools and hospitals. In return, he got power.

Huey Long was not satisfied with the power he had won in Louisiana; he had his eye on the White House. At first a supporter of the New Deal, he turned against it and began attacking Roosevelt. He called Roosevelt a “scrootch owl,” explaining that “a scrootch owl slips into the roost and scrootches up to the hen and talks softly to her. The hen just falls in love with him and the next thing you know, there ain’t no hen.” He shouted, “Every man a king!” and presented the country with his “Share-the-Wealth” plan. It called for a government allowance of from $5,000 to $6,000 for every family, the money to come from taxing the rich.

Like Huey Long, Father Coughlin had at first supported Roosevelt and then turned against him. A Roman Catholic priest, he was known as the “radio priest” for his weekly broadcasts from the Shrine of the Little Flower in Royal Oak, Michigan. He organized his followers into the National Union for Social Justice, attacked the “international bankers,” called for an “annual living wage,” and “nationalization of banking and currency and of national resources.”

Dr. Townsend, a slender, gray-haired physician of Long Beach, California, had a plan to match Huey Long’s. He wanted the government to give every citizen sixty years old or over a pension of $200 a month. The money was to be raised by a sales tax and each person who received a pension would be required to spend all of it within thirty days. This, Dr. Townsend said, would start a wave of spending and business would boom. The country would be so prosperous that no one would mind paying the tax.

THE COMMUNISTS

Roosevelt was under attack from the right; at the same time the Communists were thundering at him from the left. They attacked his program, saying that he was trying to save capitalism and that the NRA was a step toward fascism. They were active in labour unions and organizations of the unemployed and staged demonstrations in various cities.

Many American intellectuals — scientists, teachers, writers, painters, actors — supported the Communists. They feared the spread of fascism and it seemed to them that the Communists had taken the lead in the fight against fascism. With the world in the grip of a great depression, it looked as though Karl Marx’s predictions were coming true. Capitalism had indeed failed, fascism was a terrible menace and communism was the only hope of the world. Millions of people were jobless, but in the Soviet Union there was no unemployment. When it was pointed out to them that there was also no freedom in the Soviet Union, they replied that only under communism could the people be truly free, or that the Soviet Union was surrounded by enemies and could not yet afford to give its people freedom.

With the Roosevelt administration under attack from the right and the left, the world waited to see what would happen, but as Roosevelt pushed through his New Deal reforms, democracy proved to have great strength. The passing of the Social Security Act left the Townsendites without a real cause to fight for. In September of 1935, Huey Long was shot and killed, for personal reasons, by a young Louisiana doctor. The leaders of the Catholic Church showed that they did not approve of Father Coughlin, who was beginning to sound more and more anti-Semitic and he began to lose his following.

As for the Communists, they had never been able to attract a large number of Americans. Then Stalin, through the Communist International, ordered all Communists to form “united fronts” with liberals and all groups opposed to fascism. The American Communists threw their support to Roosevelt and the New Deal. Earl Browder, the head of the party, went so far as to say that “Communism is twentieth-century Americanism.”

The big test for Roosevelt was yet to come — the election of 1936. Roosevelt himself was confident of victory. In November of 1935, he said, “We will win easily next year,” then he added, “but we are going to make it a crusade.” Political observers, however, believed it was not at all certain that he would win. A number of prominent Democrats had turned against him. Among them was Al Smith, whom Roosevelt himself had once nominated for president.

Many men of wealth and position supported Roosevelt and felt that his reforms would save the existing system, but others bitterly opposed him. They called him “that man in the White House” and told stories about him, about his wife, about his sons. He was practically a communist and wanted to make himself dictator. He “ had raised taxes and was spending the money hand over fist. He was making Americans soft; why should they work when they could get handouts from the government? Why, even longhaired artists, writers, musicians, actors and dancers were living off the government! Meanwhile, businessmen were having a harder and harder time. Each day there were more government regulations, more government interference. Roosevelt had brought socialism to America. He was out to “soak the rich.” He was ruining them. He was ruining the country. Conservative newspapers echoed these remarks and kept attacking Roosevelt and his policies. A group of wealthy men formed an organization, the Liberty League, to fight Roosevelt and the New Deal.

Roosevelt was nominated by the Democrats without opposition and immediately began his “crusade.” In his speech accepting the nomination, he called his opponents “economic royalists.” He said that they “complain that we seek to overthrow the institutions of America. What they really complain of is that we seek to overthrow their power.”

The Republicans nominated Alfred M. Landon, the governor of Kansas. The Communists and the Socialists also ran candidates and there was a new party in the field — the Union party. This was made up of followers of Coughlin, Townsend, Huey Long and it nominated William Lemke. The campaign was a bitter one, but when the election returns were in, they proved that Roosevelt’s prediction had been right. He had won easily.

Even Roosevelt, however, could not have expected so great a victory. He carried every state except Maine and Vermont. He received 27,751,000 votes, while Landon received 16,679‚000. The other candidates trailed far behind. Lemke got 882,000 votes, the Socialists 187,000 and the Communists 88,000.

What had given Roosevelt such a tremendous victory? Landon was far from being the fascist that the Communists called him; in fact, he was something of a liberal, but he had been supported by the Liberty League and the people had thought of him as the millionaire’s candidate. Roosevelt, on the other hand, had seemed to be the candidate of the common man and had won the votes of labour and the big cities.