On a January evening in 1896, a famous British statesman, Joseph Chamberlain, attended a banquet in honour of an Englishman about to go to Australia as a colonial governor. Chamberlain was called upon to make an after dinner speech. What he said that wintry evening years ago explains what people at that time meant by the “British Empire” and points to the changes which he hoped would take place in the future. Here is part of what Chamberlain said:

I have heard it said that we [English] never had a colonial policy, that we have simply blundered into all the best places in the earth. I admit that we have made mistakes . . . but, after all is said, this remains –that we alone among the nations of the earth have been able to establish and maintain colonies under different conditions in all parts of the world, that we have maintained them to their own advantage and to ours, that we have secured not only the loyal attachment of all British subjects, but the general good will of the races, whether they be natives or whether they be Europeans that have thus come under the British flag. . . . Let us do all in our power by improving our communications, by developing our commercial relations, by co-operating in mutual defense and none of us will then even feel isolated; no part of the Empire will stand alone, so long as it can count upon the common interest of all in its welfare and in its security. . . . In the words of Tennyson, let

Britain’s myriad voices call,

“Sons, be welded each and all,

Into one Imperial whole,

One with Britain, heart and soul!

One life, one flag, one fleet, one Throne!”

In time to come, the time that must come, when these colonies of ours have grown in stature, in population and in strength, this league of kindred nations, this federation of Greater Britain, will not only provide for its own safety, but will be a potent factor in maintaining the peace of the world. . . .

Here we will find considerable evidence to support these words, and we will find some facts that seem to contradict them. This is not surprising, for England has made enemies as well as friends, wrong moves as well as right ones. Furthermore, in the years since Chamberlain spoke these words changes have occurred that he did not predict and the very name “British Empire” has been altered to “Commonwealth of Nations.”

Why were England’s colonial ventures of such great importance? One reason is that the British managed to hold together in common allegiance the largest group of lands and peoples the world has ever seen. Another is that Britain developed principles for ruling its empire different from those followed by most imperialist nations. Here we shall answer the following questions:

1. How did the British Empire develop?

2. How did Canada, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa win independence within the British Commonwealth?

3. How did Ireland become a separate nation?

4. How did India fare under British rule?

1.How Did the British Empire Develop?

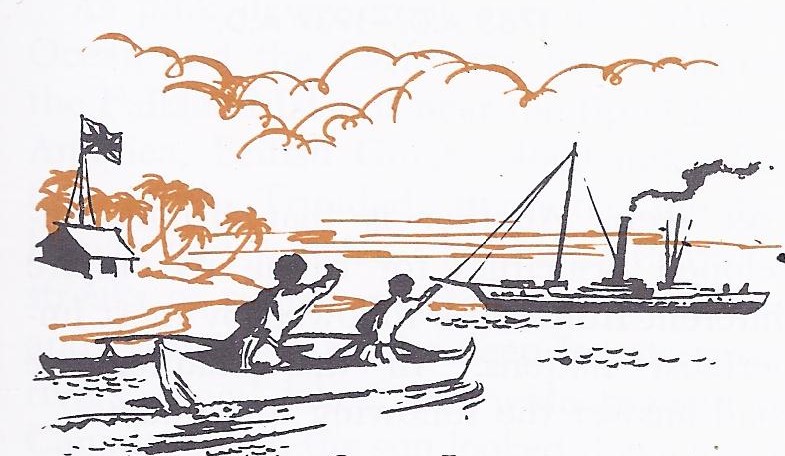

The British Empire was world-wide. Look at the map on showing the British Empire as it was in 1914. Each day when the sun rose over the waters of the broad Pacific Ocean, it shone on British flags “Union Jacks” — waving over many small islands of that vast expanse of water. As the sun moved westward it shone over Fiji, New Zealand, Australia, Papua, British Borneo, Hong Kong off the Chinese coast, Singapore and the Malay States. Then the sun brought daylight to Burma, India and Ceylon. It passed over the Indian Ocean and shone on wide British possessions in Africa-British East Africa, Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, Union of South Africa, Nigeria and many other dependencies. To the north, the sun beat down on the “steppingstones across the Mediterranean”– Cyprus, Malta and Gibraltar. Still further north it shone on the British Isles themselves.

As pink dawn crept over the Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea, it tinted the Falkland Islands near the tip of South America, British Guiana 4000 miles farther north, Trinidad, Bermuda, the Bahamas and Jamaica. To the north ruddy streaks of sunrise painted Newfoundland and Labrador, the deep forests, great rivers, broad lakes and wide prairies of Canada. Then the sun looked down again on the islands of the Pacific as a new day dawned.

While not all British possessions have been mentioned in this quick hop around the world in the year 1914, you can get some idea of the Empire’s vast extent. The saying, “The sun never sets on the British Empire” was an actual fact, not just a high-sounding phrase. Never at any other time or place in history had so many lands and peoples been brought under a single rule or enjoyed so much peace and order.

The first stage of British empire building began about 1600. Britain’s empire building falls into three separate stages. The first began about 1600 and lasted until late in the eighteenth century. During this stage the British established thirteen colonies in North America and gained a foothold for trade in India. By defeating the French in North America and India, Britain strengthened and enlarged its empire and became a leading colonial nation.

During this first stage, like all other colonial powers at this time, Britain followed the mercantile theory. According to this theory, the mother country regarded colonies as a means of increasing its wealth and regulated colonial trade to accomplish this purpose. Britain behaved, as Joseph Chamberlain said, like “a grasping absentee landlord, desiring to take from his tenants the utmost rents he could exact,” but one group of colonies, the thirteen American colonies, grew tired of being used for profit by Great Britain. When these colonies declared their independence and then won it in the Revolutionary War (1776-1783), the first stage of the British Empire came to an end.

New ideas influenced British colonial policy in the early 1800’s. The second stage lasted for nearly a hundred years, until the late nineteenth century. Loss of their American colonies caused many Englishmen to think that all colonies should be given up. It cost too much to protect colonies, they said; and colonies which were far away were likely to break loose sooner or later. “If we are certain to lose our colonies,” argued some British statesmen, “then let them part as friends, not as enemies.” During this second stage, also, new ideas were developing. It was in the early 1800’s that British thinkers began preaching the doctrine of free trade, with no tariffs or other regulations. If trade was carried on freely with all countries, colonies were less important than under the mercantile system. Moreover, the British were beginning to introduce reforms aimed at giving their citizens more rights and a greater share in government. If this idea was good for Englishmen at home, why not for English-speaking people in the colonies? In other words, let colonies have greater responsibility in conducting their affairs and let them be considered as equals rather than dependents. This change of attitude was reflected in Britain’s treatment of Canada.

A new stage of British colonial expansion opened about 1870. The widespread use of machines ushered in a new period of British colonial activity. Even under a free trade policy, Great Britain would profit greatly from colonies which could supply needed raw materials and buy manufactured products. In the scramble for new colonies the British had distinct advantages over other imperialist nations. They had more goods to sell because the Industrial Revolution had progressed further in their country than in others. They possessed the leading navy of the world to keep open the life lines between the mother country and distant lands. Most important of all, the British through past experience had learned a good deal about the management of colonies and put this knowledge into practice.

How was the British Empire governed in the early 1900’s? In the first stage of the British Empire (1600-1783) all control had been centred in London. In the third stage, from 1870 on, the supervision of colonies was neither centralized nor uniform. From time to time “Imperial Conferences” were held in London, at which political leaders from various parts of the Empire talked over problems with leading British officials, but there was no regular council, no parliament for the Empire as a whole, no common citizenship or tariff law. The colonies sent no members to the British Parliament, nor were they represented in the British cabinet. In fact, the British Empire in 1914, was a mixture of different types of control.

The British Isles themselves were completely self-governing under the name of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. Canada and Newfoundland in North America, South Africa, Australia and New Zealand were called “Dominions” and possessed a large degree of self-government. Much of India was governed by the British as a separate and special Empire. Then there were countries like Egypt and the native states in India which the British ruled indirectly. In these countries British advisers (backed by soldiers) were sent to “help” the native rulers. Finally there were many other British possessions, such as islands in the West Indies and parts of Africa, which were “crown colonies.” Some of these crown colonies were governed directly by British officials. Others had legislatures of their own under a governor and officials chosen by the British home government. This latter kind of government was very much like that which had existed in the thirteen American colonies before 1776.

The Crown was a symbol of unity. What held this vast and varied empire together? One answer lay in the British Crown. To Americans the Stars and Stripes is the chief symbol of their native country and of the privileges which they enjoy as its citizens. The British have not only their flag, but another symbol in the person of the king or queen.

It is true that British sovereigns do not actually rule. During the last hundred years and more they have acted according to the advice of their cabinet ministers. Nevertheless, some of Britain’s monarchs during the past century have exercised considerable influence. There is no question that the British king or queen has served as a symbol of unity which helped bind the Empire together. Statesmen might rise to power and lose office; party policies might change — but the royal sovereign has continued to stand as a common bond of affection. He or she is the connecting link between the past, the present and the future — and between all parts of the Empire.

The navy was another bond of union. The British Empire was an empire of the seaways. It was important that communications between the mother country and the colonies be kept open. Otherwise England might be cut off from India, India from Australia, Australia from Canada, Canada from British Africa and so on around the world. The whole Empire would then be like a chain of beads when the string was broken. To make sure this would not happen, the British maintained a navy strong enough to protect their possessions from any foe.

There were strong ties of sentiment. In independent parts of the Empire such as Canada, Australia and New Zealand, there was a very special bond a feeling of attachment for the mother country. By 1914 these regions controlled most of their affairs. They could not be forced to remain in the Empire, but they did not want to break away. These people were, in large part, of English origin. They had a double sort of patriotism. They felt a strong love for their own land, but they also had a strong attachment to the mother country from which their ancestors had come.

A simple illustration of this double loyalty could be found in national songs. At public ceremonies in Canada, Australia, New Zealand or South Africa the British national anthem, “God Save the King (Queen),” was always played, but each of these countries also had its own national song. In Canada on British Empire Day, the people would sing in English or French:

O Canada! Our home and native land!

True patriot love in all thy sons command.

With glowing hearts we see thee rise

The True North strong and free. . .

On that same holiday in Australia would be heard the words of “Advance; Australia Fair.” Here are the first lines:

Australia’s sons, let us rejoice

For we are young and free.

And in New Zealand, the words of the national anthem of still another free people would ring out:

God of Nations! At Thy feet

In the bonds of love we meet;

Hear our voices we entreat

God defend our Free land.

In South Africa also the people had their own anthem. This song was written by a Boer, in the language of the Boers. Its first lines reflect the courageous spirit and common purpose of these pioneers:

From our lonely trails and veldt paths

Where the wagons onward roll,

Comes the voice that is her people,

Comes the call of soul to soul.

Underlying these ties of a common sovereign, a powerful navy and the bonds of affection was another reason for Britain’s colonial success — its ability to deal with changing conditions. We learn further how British and colonial states worked out new forms of government to meet new needs.

2. How Did Canada, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa Win Independence Within the British Commonwealth?

Of the several members of the Commonwealth of Nations today, Canada is the oldest. It was here that the British first tried out the principle of independence within the Empire.

British control of Canada was followed by “responsible government.” Recall for a moment some of the facts of Canada’s early history. You will remember how the French settled the lower St. Lawrence valley but became British subjects after France was defeated in 1763. We know also that Upper Canada was settled by Loyalists who left the United States because they wanted to continue to live under the British flag. Later immigrants from England, Scotland and Ireland swelled the number of English-speaking people in the country.

You will remember, too, that there was a good deal of dissatisfaction in both Lower Canada and Upper Canada. When Britain accepted Lord Durham’s suggestion and granted Canada “responsible government,” this dissatisfaction ceased. “I propose,” Lord Durham had written, “to concede the responsibility of the colonial administration . . . to the peoples themselves. . . . The Crown in England [will] henceforth consult the wishes of the people in the choice of its servants.” By granting responsible government to Canada, Britain not only managed to keep Canada within the British Empire, but started a new imperial policy. This new pattern of independence within the Empire was extended to other regions. It led in time to the formation of the British Commonwealth of Nations, recently renamed the Commonwealth of Nations.

Early Canada was not only undeveloped but lacked unity. Around 1850 the name Canada did not have the same meaning that it has today. It referred only to Upper and Lower Canada, now the provinces of Ontario and Quebec. To the east were the maritime or seaboard colonies of Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island. These had self-government but were not regarded as part of Canada. To the west lay open prairies (now the provinces of Manitoba and Saskatchewan and eastern Alberta). Still farther west rose the towering Canadian Rockies in what is now western Alberta and British Columbia. In the 1850’s there were only widely separated settlements and trading posts in this western area. To the north lay the wilderness of the Hudson Bay region and the endless “barrens” inhabited only by wandering Indians and a scattering of fur traders. Farther north still, on the shores and islands of the Arctic Ocean, was a thinly scattered population of primitive Eskimos.

Canadians took steps to unite. For a number of reasons a movement got under way to unite these scattered regions. Disputes had occurred on several occasions during the nineteenth century between Canada and its neighbour, the United States. A united Canada could speak with greater authority and more effectively defend its interests. Another reason for seeking unity was the lack of good transportation. A united Canada could better build railroads and highways to span the continent. Representatives from Canada and other British North American colonies met at Quebec to draw up plans for union. They prepared a constitution for a United Canada. This constitution was approved by the British Parliament in the famous British North America Act and went into effect July 1, 1867. For this reason Canadians celebrate July 1, the day Canada became a Dominion.

At first only four provinces joined the Dominion of Canada — Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. The map shows when other provinces became members of the Dominion. Before some areas were admitted as provinces, they had to grow in population, much as the territories of our own wide-open West had to be settled before they could become states. When Newfoundland joined the Dominion in 1949, it brought the number of provinces up to ten.

The Dominion government included British and American features. Under the British North America Act the Dominion of Canada, like our own country, became a federation of states. Each state or province has its own government, but the Canadian provinces have less power than our states. Any powers not granted to the provinces by the Canadian constitution belong to the central government. In our country it is just the opposite, for all powers not granted to our federal government belong to the states.

The British North America Act set up the framework of government under which Canada still operates. There is a legislature of two houses, a Senate and a House of Commons. Members of the Senate are appointed for life by the cabinet rather than elected as in the United States. Members of the House of Commons are elected by the people as are members of our House of Representatives. Instead of a president, the leader of the party in power in the Canadian House of Commons becomes the chief executive as is the case in Great Britain. This leader or Prime Minister chooses the Canadian cabinet. He remains in power only so long as his party can count on a majority of votes in the House of Commons. As you see, the central government of Canada resembles the British plan more than ours.

Canadians managed their own affairs. Under the new Dominion government Canadians were practically independent. They made their own laws, provided for local defense, set their own taxes and decided how funds should be spent. They even had a tariff on goods that came from Great Britain, though tariff rates on British goods were usually lower than those placed on goods from other countries.

In short, except for the management of foreign relations and defense of the Empire, England no longer had any real authority over Canada. Britain’s king or queen was regarded by Canadians as their ruler and was represented by the Governor-General, but the idea that the “sovereign reigns, but does not govern” was as true in Canada as in Great Britain.

Canada has become a great nation. In 1867 when the Dominion was formed, Canada was still largely undeveloped. Its population was small, owing partly to lack of good means of transportation between its widely separated parts, but the Canadians set to work with a will. In 1885 the Canadian Pacific Railway was completed, joining the western and eastern provinces. Also, immigrants were encouraged to settle in Canada. The number of Canadians increased from 2 million to some 11 million in 1939. During the present century Canada has become a prosperous country whose citizens have a high standard of living. The large farms of the western provinces, operated by modern farm machinery, produce much wheat for export. Canada’s plentiful and valuable natural resources have stimulated important industries. Its mineral wealth includes iron, coal, oil, copper, nickel, considerable deposits of gold and rare metals such as uranium. Its forests provide timber for wood and paper products and its waters yield large quantities of fish. A vast amount of power is locked up in Canada’s many streams and waterfalls. Important manufacturing cities have developed along the St. Lawrence and the Great Lakes. The volume of trade between the United States and Canada is very large. Canada, in truth, is one of the leading nations of the modern world. During World Wars I and II, it was a tower of strength to the whole British Empire.

The British rediscovered Australia. On the opposite side of the world from Canada is Australia. In the 1600’s when the Dutch were settling New York, other Dutchmen were exploring the Pacific. They discovered a very large island or continent which they called New Holland, later named Australia. Australia is nearly as large as the United States’ first 48 states, but its population was too small and poor to attract the Dutch, who chiefly sought trade. They felt it would be more sensible to centre their activities in thickly populated areas such as the East Indian island of Java. So England’s famous explorer, Captain James Cook, who “rediscovered” Australia in 1770, claimed it for the British.

At first the British attached little value to this distant possession. There was some talk of sending out loyalists who had been driven from their homes by the American Revolution, but the Loyalists, preferred Canada. Moreover, sailing vessels took months to make the long voyage from Great Britain to the continent “down under” — on the opposite side of the globe, but events since that time have proved that Captain Cook’s discovery was a lucky accident for the British.

Australia’s first European inhabitants were convicts. The British government first used Australia as a colony to which they could send convicts. In those days British laws were harsh and punishment severe. Many people who were sent to prison were not hardened criminals. Some had been unable to pay their debts; others had committed minor offenses. Sending such persons to far-off Australia seemed an easy way to empty Britain’s overcrowded jails. As one witty convict put it: “True patriots we; for be it understood, we left our country for our country’s good!”

After serving their time as unpaid labourers, these convicts became free men and could obtain land. They settled down as free citizens. Many of the soldiers and police officers sent to guard them also remained. In the 1860’s the British stopped sending out convicts. Australia did not want to be regarded as a “convict colony.” Besides, as British laws had become less severe, there were fewer convicts.

Free British settlers took over Australia. The former prisoners and ex-guards were in time joined by many more people who went to Australia of their own free will. These immigrants were attracted not only by opportunities for wheat farming and sheep ranching, but also by the discovery of gold and other minerals. As white settlers increased in number, they pushed Australia’s scattered native tribes into the interior. The English government and later the Australians themselves, took steps to bar non-white peoples from settling in Australia. As a result, Australians are very largely British in ancestry and background. Between 1837 and 1871 Australia’s population skyrocketed from 150,000 to more than 1,600,000! Settlements multiplied and railroads and telegraph lines were built.

Australia became a self-governing Commonwealth. Englishmen, wherever they were, wanted to govern themselves and the Australians were no exception. Due to great stretches of desert and marshland, Australia’s early settlements were widely scattered. Separate colonies therefore grew up. By about 1855 the British Parliament had given these colonies the right to rule themselves. Then, as the rivalry among European nations for trade and possessions in Asia and the South Pacific became more intense, Australians became interested in forming a confederation of colonies. They were particularly troubled over Germany’s growing colonial power in the Pacific area. Their desire for union led Australians to hold a series of constitutional conventions. The delegates carefully studied the Constitution of the United States and modelled their own constitution in part after ours. On January 1, 1901, after the federal constitution had been accepted by the Australian voters and approved by the British Parliament, the Commonwealth of Australia was born.

The Commonwealth of Australia gives more power to the states into which it is divided than Canada allows its provinces. An elected Senate represents the states and a House of Representatives represents the people. This setup somewhat resembles that of our Congress, but as in Canada and England, the chief executive is a prime minister who is the leader of the majority in the lower house of the legislature. Australia thus follows the plan of “responsible government.”

The British also colonized New Zealand. About 1200 miles southeast of Australia is a group of islands called New Zealand. The two principal islands, taken together, are larger than Great Britain. About a third of Australia has a tropical climate, but all of New Zealand has a cool, moist climate somewhat like that of the British Isles. New Zealand is one of the leading sheep-raising countries of the world.

The British long had traded in New Zealand with the Maoris, who were a brave and fierce Polynesian people, but it was not until 1840 that the British raised their flag to claim the islands and they did so chiefly to prevent France from getting them. New Zealand remained a separate self-governing colony until 1907 when it became a Dominion. Unlike Australia, it has a centralized government; there are no states as in the Australian federation.

Australia and New Zealand pioneered in political and social reform. Australia and New Zealand adopted certain democratic procedures in advance of other countries. For example, Australia introduced the secret ballot in the 1850’s. This form of voting has been adopted by other countries and is still known as the “Australian ballot.” Both Australia and New Zealand adopted universal adult suffrage (by which all men and women could vote) at an early date. In fact, in 1893, New Zealand was the first country to give women the vote on equal terms with men.

Both countries likewise have adopted social reforms. These include laws providing for old-age insurance, workingmen’s insurance against accident and unemployment and the compulsory settlement of labour disputes by unprejudiced outsiders. As a result of heavy taxes on incomes and inheritances and government spending for social security, few people are very rich or very poor. Certain industries are operated by the government.

The South African Union developed after the Boer War. So far in this section you have followed the story of three countries which gained independence within the British Empire — Canada, Australia and New Zealand. The story of the fourth, South Africa, was different, even unusual. We’ve learned how the Boers in South Africa lost their independence in the fiercely-fought Boer War. The British, however, treated the defeated Boers generously. In 1909 the former Boer republics — the Transvaal and the Orange Free State — joined with the British colonies of Natal and Cape Colony to form the federal Union of South Africa.

In this Union the Dutch (Boer) and British inhabitants had equal rights and privileges, like the French and British in Canada. In fact, the Boers were able to elect their leaders as prime ministers of the whole Union. The first three prime ministers had been generals in the Boer War. Thus, only a few years after a bitter war, a defeated people was able to outvote its conquerors and elect generals of the losing side to the highest office.

A race problem developed in South Africa. Yet South Africans faced a disturbing problem. Englishmen and Boers were greatly outnumbered by the native African population. A relatively few Europeans ruled over large numbers of Africans who had almost no share in the government. There developed among the descendants of the early Dutch settlers a fierce determination to preserve European supremacy. A serious race problem resulted from the harsh measures adopted to preserve this goal. (Because of sharp criticism of its racial policies, South Africa broke its ties with the British Commonwealth in 1961 and became an independent republic.)

Great Britain came to treat its Dominions as equals. By becoming Dominions, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa gained control of their affairs at home. The British government in London, however, took the lead in foreign affairs and matters of common defense. As time went on, Britain treated the Dominions more and more as equals. Beginning in the late 1800’s, Imperial Conferences were held at London. At these meetings British statesmen and representatives from the Dominions discussed problems of common interest. When World War I broke out, the Dominions rallied to the support of the mother country. Dominion troops fought side by side with the British. After the war, the Dominions felt they had earned the right to take part in the peace conferences and to speak for themselves.

The British Empire became a Commonwealth of Nations. An Imperial Conference held in 1926 issued a momentous statement. It declared that Great Britain and the Dominions were “equal in status, in no way subordinate to one another in their domestic or foreign affairs, though united by a common allegiance to the Crown and firmly associated as members of the British Commonwealth of Nations.” Each Dominion, then, was to have control of its foreign affairs and the right to make decisions on war and peace. Five years later, in 1931, the Statute of Westminster formally established “The British Commonwealth of Nations.” (The word “British” was dropped in 1949.) Each Dominion was now “master of its destiny.” Thus the gradual growth of the Dominions to nationhood, begun with Lord Durham’s report in Canada about a hundred years before, was completed.

3. How Did Ireland Become a Separate Nation?

The British, adopted wise policies which brought independence to Canada, Australia and New Zealand, yet at the same time retained their loyalty to the mother country, but in their dealings with one portion of their Empire, Ireland, the British were much less successful.

Ireland presented a problem of nationality. The story of Ireland’s struggle for self-rule is a long and unhappy one. The Irish are a proud people with a different background from that of the English. The early Irish were Celts, whose land was invaded by Vikings and in the later Middle Ages, by English kings. The Irish bitterly resented the attempt of the English to conquer them and rose in rebellion again and again. These rebellions were harshly put down. In 1801 the British further aroused the Irish by doing away with the separate Irish Parliament. Thereafter the Irish were represented in the Parliament in London. Thus the Irish regarded themselves as a people placed under foreign rule against their will.

Ireland was divided by religion. Another source of trouble was religious differences. Back in the 1600’s a large body of Scottish immigrants settled in northern Ireland (often called Ulster). These people were Protestants, as were the majority of the people in Great Britain, but the people in the rest of Ireland were Roman Catholics. The lot of the Catholics was not a happy one. (1) They were forced to help pay for the support of the Church of England (Protestant) which was established as the official church in Ireland. (2) Due to their religion the Catholics were barred from sitting in the British Parliament and could not hold public office. (3) Their children usually had to attend either Protestant schools or none at all.

Differences in religion also affected the people’s point of view about government. The Protestant Irish, mostly in Ulster, wanted to remain within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. They were called “unionists.” The Catholics in the rest of Ireland wanted “home rule” for Ireland and became known as “nationalists.”

There was much poverty in Ireland. The Irish people also objected to the landholding system. Large tracts of land in Ireland had been given to British landlords. These landlords rarely visited their estates and left the management to agents. The agents took little interest in the tenant farmers on the estate. Unfortunate tenants who could not pay the high rents were forced off the land.

There were few industries, so most of the people depended on farming for their living. Farm production, however, did not keep up with the growth of population. When the potato crop failed in the 1840’s, thousands died from famine. Large numbers left Ireland to find new homes. Some went to work in British factories, some settled in Canada and Australia, but most of those who left home came to the United States. From 1850 to 1880 more people came to the United States from Ireland than from any other country.

Some reforms were adopted. Conditions in Ireland improved somewhat as a result of certain reforms. (1) In 1829 Roman Catholics were allowed equal political rights with Protestants and could serve as members of Parliament. (2) Forty years later all religious groups in Ireland gained equal rights. (3) After the failure of the potato crop and the resulting famine, Parliament passed laws which protected farmers in Ireland from losing their homes and from having to pay excessive rent. The British government also lent money to Irish farmers to help them to buy land for themselves.

Ireland still demanded home rule. The Irish nationalists were far from satisfied, however, with the reforms that had been granted. They urged the British statesman Gladstone, who had helped bring about religious and land reforms, to give Ireland its own parliament. This he promised to do, but some members of Gladstone’s own Liberal (Whig) Party joined with the Conservative (Tory) Party to oppose Irish home rule. Two home-rule bills introduced in the 1880’s and 1890’s failed to pass.

Meanwhile the spirit of Irish nationalism was growing. The Irish took new interest in their ancient legends, ways of living and language. A new society called Sinn Fein (meaning “We Ourselves”) did much to foster the new spirit of nationalism.

The Irish Free State was born. Ireland did not receive home rule until after World War I. A home-rule bill introduced in 1914 was fiercely opposed by the people of Ulster who did not want to become part of an independent Irish state. The nationalists, on the other hand, were angry because no action was taken on home rule during the War. Some of them rose in rebellion against the British during the bloody “Easter week” of 1916. Serious unrest prevailed in Ireland for several years.

In 1922 a new plan was tried. Northern Ireland received a Parliament of its own, although it was still represented in the British Parliament. The southern part of Ireland was made a Dominion, like Canada or Australia. It no longer sent members to the British Parliament. This new government was called the Irish Free State or (in the old Celtic language) Eire. The Irish Free State had the power to make its own tariffs and even to tax British goods coming into the country.

Eire became an independent state. Conditions improved considerably under the Irish Free State. The government put through reforms so agriculture and industry prospered, but some of the nationalists were not satisfied with being a Dominion; they wanted to be completely free of Britain. Chief among this group was Eamon De Valera, who was born in the United States. Under De Valera’s leadership, Eire adopted a new constitution and became practically independent. During World War II Eire remained neutral and in 1949 it cut the last bonds with Britain. After centuries of unwilling subjection to British rule, Eire became a completely independent nation.

4. How Did India Fare Under British Rule?

We come now to the story of another part of the British Empire which today is completely independent. Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the Union of South Africa were thinly populated regions settled by the British and other Europeans. This was not true of India, heavily populated by a people whose civilization was deeply rooted in ancient times. We have read how the British gained a firm foothold in India. What policies did Britain develop in India? How did the people of India react to Western influence? How did a nationalist movement get under way in India?

The British East India Company dominated Indian affairs. At the outset you need to recall these three facts about India in 1850: (1) England governed directly only parts of India. Much of the land was still ruled by native princes. (2) The British government kept in the background, providing military support only when needed. (8) The day-to-day government was left to officials of the powerful and immensely rich British East India Company. Many parts of the British Empire had been built up by the energy of chartered companies, but none built on as grand a scale as the British East India Company.

Parliament set-up regulations for the East India Company. When the vast power of the East India Company led to corruption among its officials, Englishmen insisted that the Company clean house. Beginning in 1784 Parliament took over the governing activities of the East India Company, though the Company still remained in private hands. The highest official of the Company in India, for example, was to be appointed by the government in London.

Reforms were introduced to protect the rights of the Indian people and to improve their lot. The new governors of the Company deserve credit for ending certain evils. They put a stop, for example, to the practice of killing unwanted infant girls. They forbade widows to commit suicide by leaping into the fires which burned their husbands’ bodies. They broke up the “Thugs,” a society whose members were required to commit murder to honour their goddess Kali.

By trying to change ways of living too quickly, however, Company officials sometimes angered the people. Often they unwisely ignored religious customs. For example, they attempted to have some of the sepoys (native troops) handle gun cartridges that had been greased with animal fat. This practice angered the Hindus, to whom the cow was sacred and the Moslems, whose religion forbade them to touch pork. Serious trouble followed.

In 1857 the Sepoy Mutiny broke out. The East India Company had some British regiments, but most of its soldiers were natives. When a number of the sepoy regiments mutinied, some of the Indian princes joined them in an effort to get rid of British rule. Had all India acted together, the British would have been defeated, but the people of India in those days lacked unity. There were many races, languages, classes and religions. Many provinces and native states remained quiet and some native troops stayed loyal to the British. The masses of people simply went on tilling their crops and took no sides in the conflict. After a few months of hard fighting, the rebellion was crushed and the British re-established their control of India.

The British government assumed control of British India. The Sepoy Mutiny made it clear that Britain could no longer expect to control India through a private commercial company. In 1858, therefore, the British government decided to take over direct responsibility for India. The officials of the East India Company were transferred to the India Civil Service of the British government. In 1876 Parliament gave Queen Victoria the new title of Empress of India.

In taking over its new duties, the British government: (I) assured the people of India that rebels except those who had committed murder would be pardoned; (2) promised that the Christian religion would not be forced on people of other faiths; (3) agreed that the native peoples of India would have the same right to enter the India Civil Service as British subjects; (4) declared that native princes would be left on their thrones.

The British government held a firm grip on India. At the head of the government of British India was a Viceroy, or royal governor, appointed by the British home government. He worked in co-operation with a Secretary for India in the British cabinet. British India proper, governed directly by the Viceroy and the officials of the India Civil Service, included about three-fourths of the whole population. The rest of the people lived under native rulers who had various titles. At each native court, however, there was some British “resident” or “agent” who was there to give “advice” to the ruler. As the adviser had the full force of the Empire behind him, his suggestions usually were heeded. This arrangement helped British control, for it kept India divided and also delayed the growth of national spirit.

A new national feeling arose in India late in the nineteenth century. On the whole, British India was well governed. Except on the borders, where tribesmen sometimes carried on raids, there was no war. The population increased rapidly. Universities were founded, dams and railroads were built, new industries were introduced.

The people of India were not content. Most of them still lived in such grinding poverty that the failure of a single crop resulted in thousands, even millions, of deaths from starvation. Particularly among the small but growing class of educated Indians, a new type of nationalism was developing. This movement looked toward the future rather than the past. Indian leaders talked about such Western ideas as democracy and nationalism. These leaders declared that much of India’s wealth was not being used to benefit the Indian people. Moreover, they knew that independent Asian nations like Japan had become modern and progressive. “Why not India, too?” asked these Indian nationalists.

Some of them did more than ask that question. Sometimes discontent took the form of riot and assassination; sometimes, of strikes and boycotts; sometimes, of peaceful political movements, but what these leaders really wanted, they said, was self-government. In 1886 the Indians formed the National Congress, an organization which included a number of political parties. Members of the Congress, who came from all parts of India, discussed their grievances against the British. The Congress became the most powerful influence for Indian home rule.

Britain extended home rule in India. To meet the rising national feeling among the educated people of India, the British made some changes. More Indians were taken into the Civil Service. Wider powers were granted to elected councils in the provinces. An Indian was included in the viceroy’s council, but reforms moved haltingly. The British were slow to act and the native princes were not eager for changes which might reduce their power. What was more important, the chief religious groups — the Hindus and the Moslems — distrusted each other. They could not work together in a common cause.

Britain announced a new Indian policy. When World War I broke out in 1914, India co-operated with Great Britain. About 1,400,000 volunteers from India took part in that conflict and native princes contributed large sums of money. Such loyalty led Britain to state that gradually the same form of self-government would be introduced in India as already existed in Canada, Australia, South Africa and New Zealand. This marked a great change in policy. Until 1914 the British had seemed to believe that only people of European descent could govern themselves. Now Great Britain was saying that the people of India should also be given self-government. The old notion of “The White Man’s Burden” was melting away.

Gandhi led a peaceful revolution. Britain’s program of gradual extension of self-government to India, however, did not go far enough or move swiftly enough to satisfy the National Congress. As a result, members of the Congress started a “peaceful revolution” in India. The leader of this movement was a small, thin, frail-looking man named Gandhi. His faithful, devout Hindu followers called him the “Mahatma,” meaning “Saint.” Working closely with Gandhi was another Hindu named Nehru.

Gandhi preached that the Hindus and other Indian peoples should get the British to leave India without resorting to violence. Let no one carry his case to a British law court, or pay a British tax, or buy from a British merchant and Gandhi predicted that India would soon be free. For instance, when the British levied a tax on salt, Gandhi dipped sea water into a pan, let the water evaporate and so made his own salt. He urged his followers to make their own cloth with old-fashioned spindles, spinning wheels and hand looms.

Gandhi’s campaign got him into trouble with the British government and he was sent to jail several times. Such happenings only spurred the Mahatma’s devoted followers to further acts of “civil disobedience.” In 1985 Parliament tried again to solve the Indian problem by passing a new Government of India Act. Though it provided for increased self-rule, this act also failed to satisfy India’s nationalists. They insisted that under it India would still be without Dominion rank and that the British Parliament and the British governors in India would still have too much power. So demand for complete self-government continued.

Did British rule help or hinder India? English industrial and business interests controlled most of India’s trade and resources after 1850. They flooded India’s market with English-made goods and hurt many of India’s small local industries. India nevertheless did develop industries, especially after World War I. Cotton mills and steel mills increased in number. Some of the largest cotton mills in the world are in India. By 1935 steel production had risen to 880,000 tons yearly — an amount exceeded by only about a dozen countries at that time. Such industrial growth, however, brought few changes for the vast majority of the people. Most of them continued to live in small villages and to till the soil; but India had other troubles, too. In spite of irrigation dams and some improvement in farming methods, farmers could not grow enough food to take care of the rapidly increasing population. Many people in India did not have enough to eat. Moreover, disease ran riot among the people both in the overcrowded cities and in the villages. As late as the 1930’s the average span of life in India was only 26.5 years, contrasted to more than 60 years in the United States.

In India education lagged. The people of India also suffered greatly from lack of education. One reason for this was that the learned class for centuries had been set apart from other classes by the caste system. There were language and religious differences as well. Above all, most people were wretchedly poor.

To be sure, the Indians had schools of their own and the British started a system of public education early in the 1800’s. By 1938 India had 18 universities and 261 colleges. Nearly 12 million boys and young men and about 2 million girls and young women were in schools or colleges at that time, but education affected only a small portion of the huge population. At the end of World War II only one person in eight in India could read or write.

India was a ”house divided against itself.” India’s caste system, the tension between Moslems and Hindus, the many native states and their rulers, the many languages — all tended to keep India disunited. Even the members of the National Congress could not always agree. Such was the situation when World War II broke out in 1939.

What began as a program to unite Canada and establish self-government there was extended to other lands within the British Empire. This principle of greater independence was formalized by the creation of the Commonwealth of Nations. As the chart indicates, two of its earlier members have left the Commonwealth, but a number of new members, mostly in Asia and Africa, have been added in the period since 1945.