Caliph of Cordova’s library, raised Cordova to its great eminence. It was Europe’s most glittering capital: a place where Moslems, Christians and Jews lived, worked, studied and thought. Tenth-century Cordova was as preoccupied with philosophy, poetry and medicine, as Paris was to become in the eighteenth century. Spain’s intellectual ferment was a product of the recently established Islamic society, but it was also concerned with the old, with preserving the ancient learning of Greece and Rome. Toward the end of the century, the Caliph Al-Hakam II, gathered a library of four hundred thousand books and manuscripts, indisputably Europe’s finest collection of writings on history, science and literature. The library was largely destroyed by a fanatical successor and Cordova’s days of greatness drew to an end.

Cordova, under its great caliphs of the tenth century, was the most splendid city of Western Europe. Ash-Shaquandi, the poet who sang the praises of his native al-Andalus (Andalusia) says that he rode for ten miles on end through its well-lit streets. A fine bridge spanned the river, which still bears its Moorish name of Guadalquivir and on either side stretched the quarters of the dominant Moslem population —Arabs and Berbers from Africa, as well as descendants of Spain’s indigenous inhabitants who had embraced Islam and communities of Jews, Christians (Mozarabes) and slaves from Eastern Europe. One traveller counted 300 public baths; another, 600 — a number perhaps not excessive for a population of over half a million, though it scandalized medieval Christians.

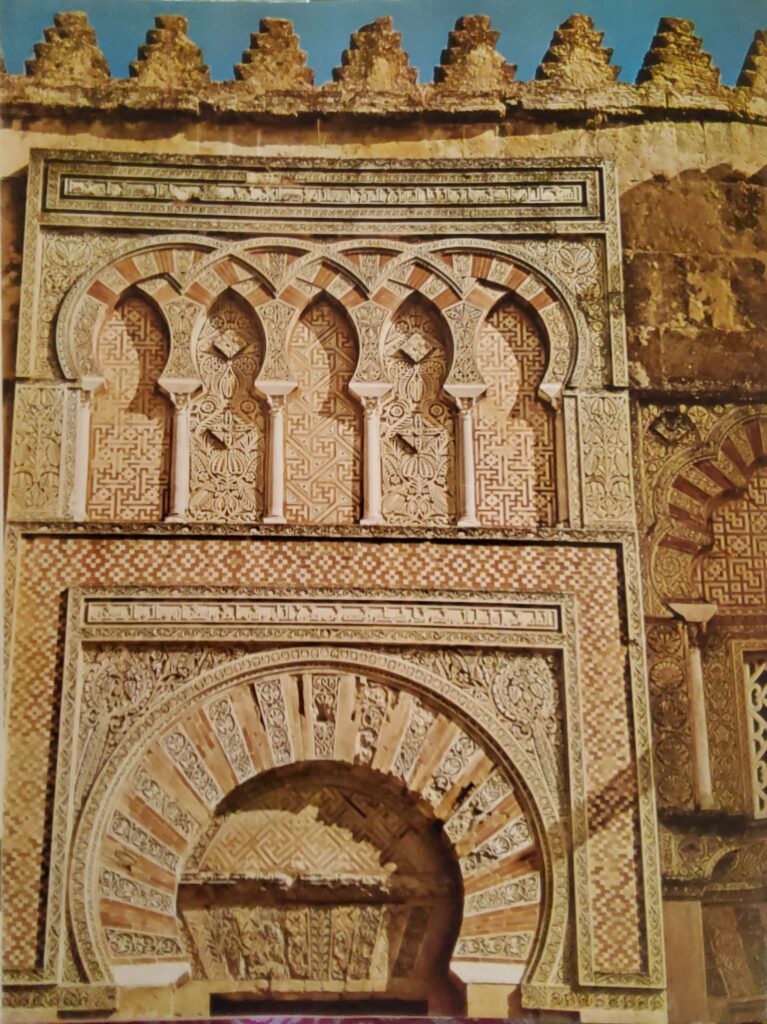

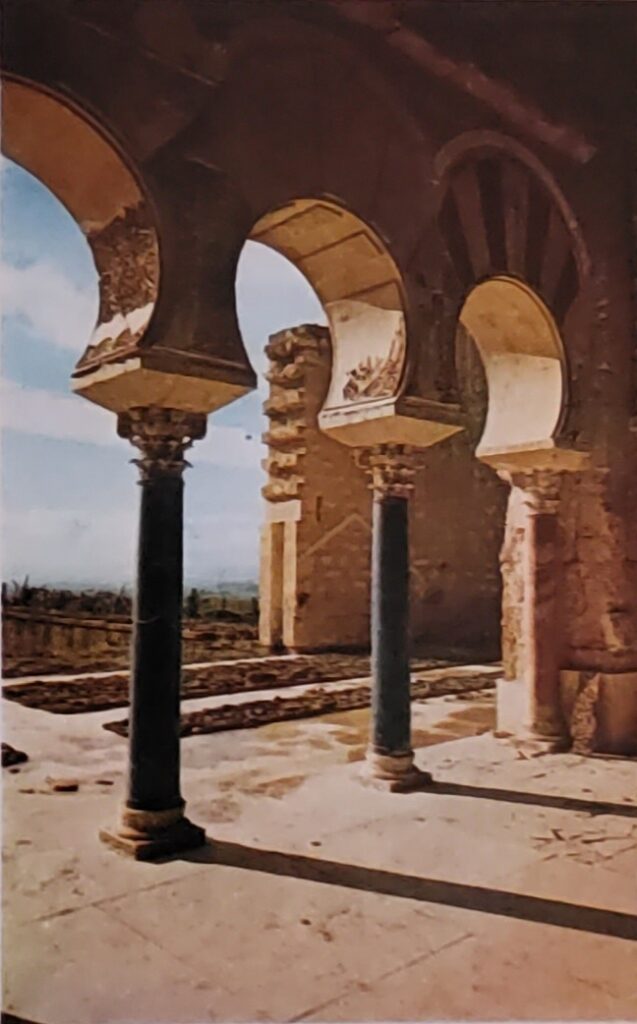

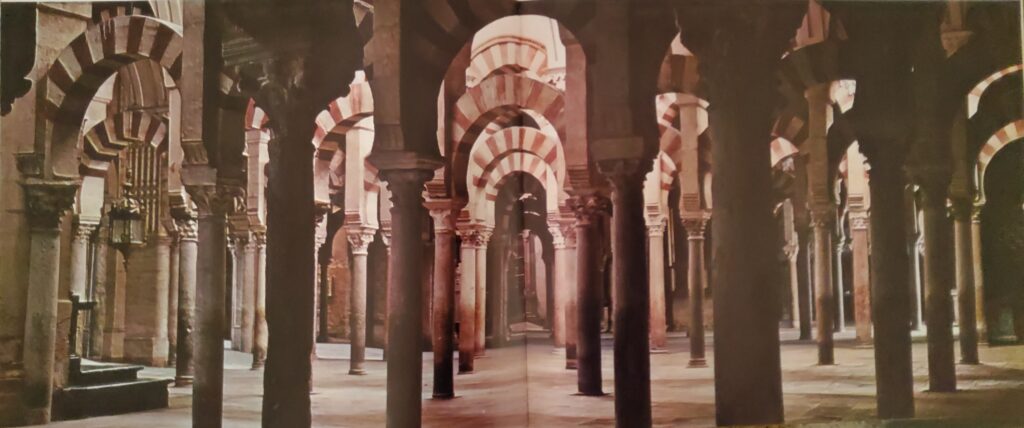

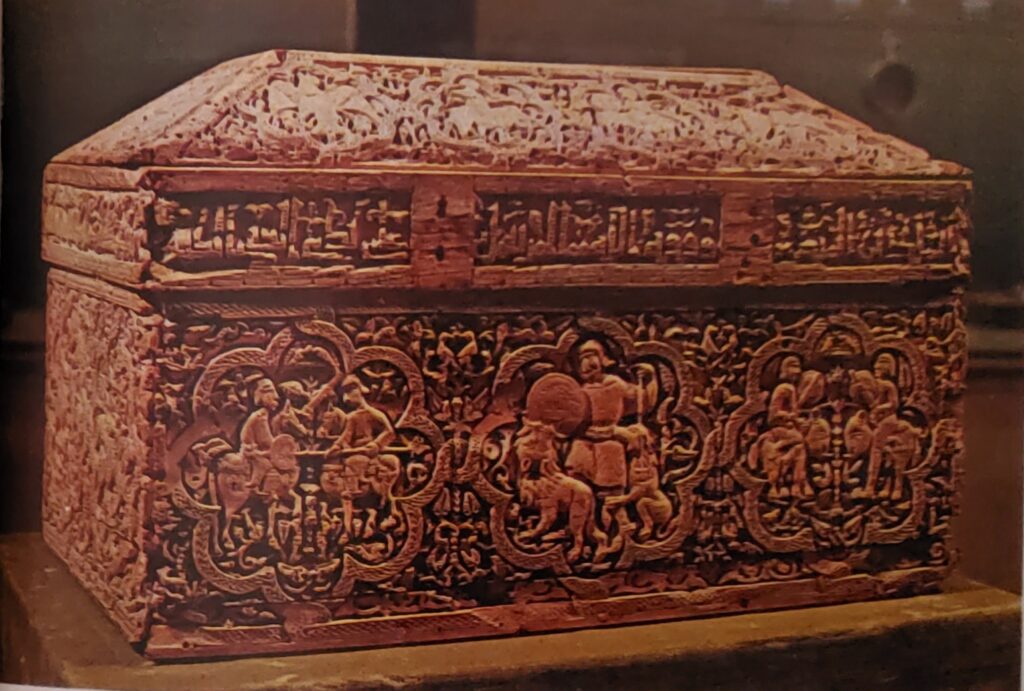

Cordova’s other marvelous sights included innumerable workshops for the production of its famous leatherwork, carpets, ivory caskets and other handicrafts; more than four thousand markets and many hundreds of mosques in addition to the Great Mosque. Although later converted into a Catholic cathedral, this remains one of the supreme glories of Moslem Spain. There were also the gracious residences of the rich, set amidst lovingly cultivated gardens; and the superb palaces of al-Madina — az-Zahira and Medinat az-Zahra, the latter a great administrative and ceremonial headquarters for the Caliphate as well as a palace of unparalleled magnificence. In view of its subsequent history however, the Caliph’s library built up in the tenth century is of paramount importance.

Cordova was more than the seat of a powerful and prosperous empire. It was also, in the words of ash-Shaquandi, “the centre of learning, the beacon of religion, the abode of nobility and leadership; its inhabitants had deep respect for the Law and set themselves the task of mastering this science. Kings humbled themselves before the doctors, exalting their calling and acting in accordance with their opinions.” During his long reign, first as Emir and then as Caliph, Abd-al-Rahman III (912 – 61) raised Cordova to its eminence. A great soldier and administrator, he was also a tireless builder and a munificent patron of learning and the arts.

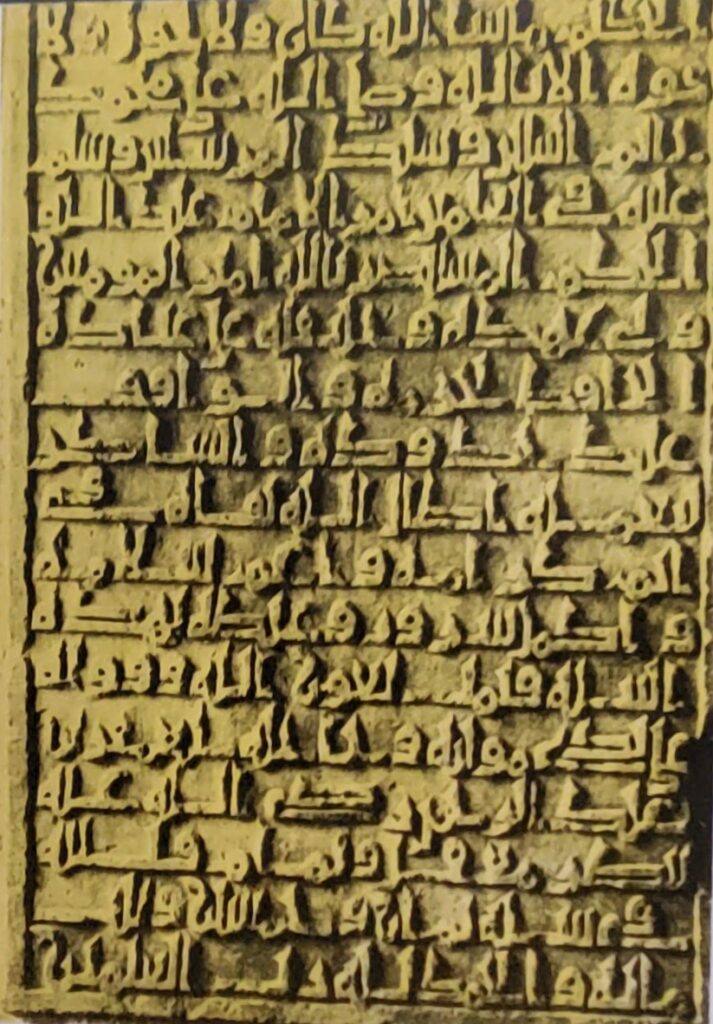

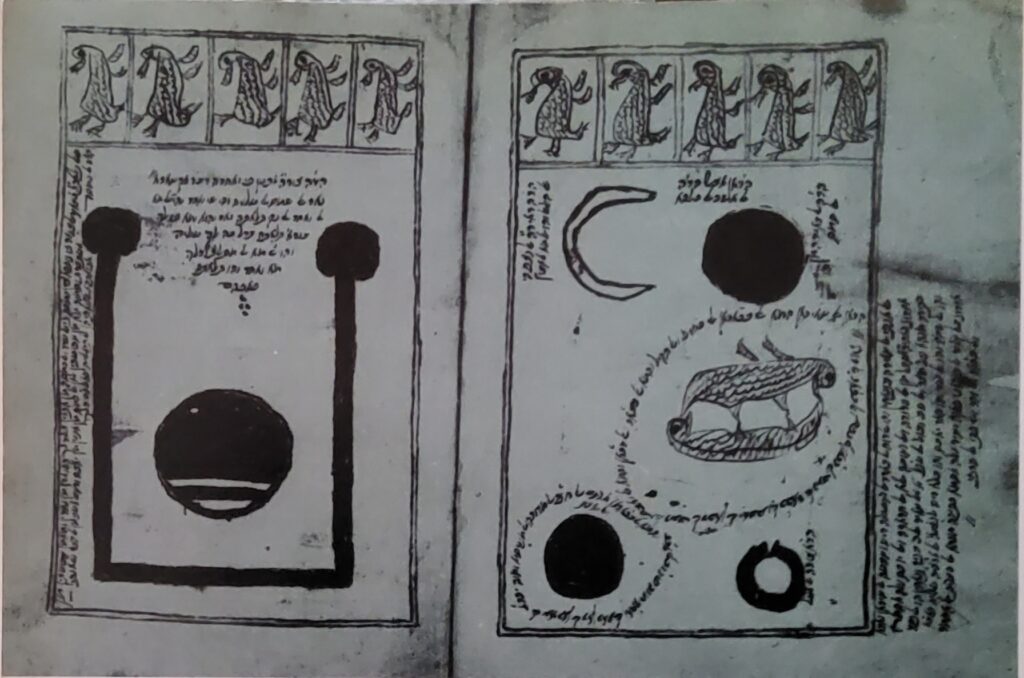

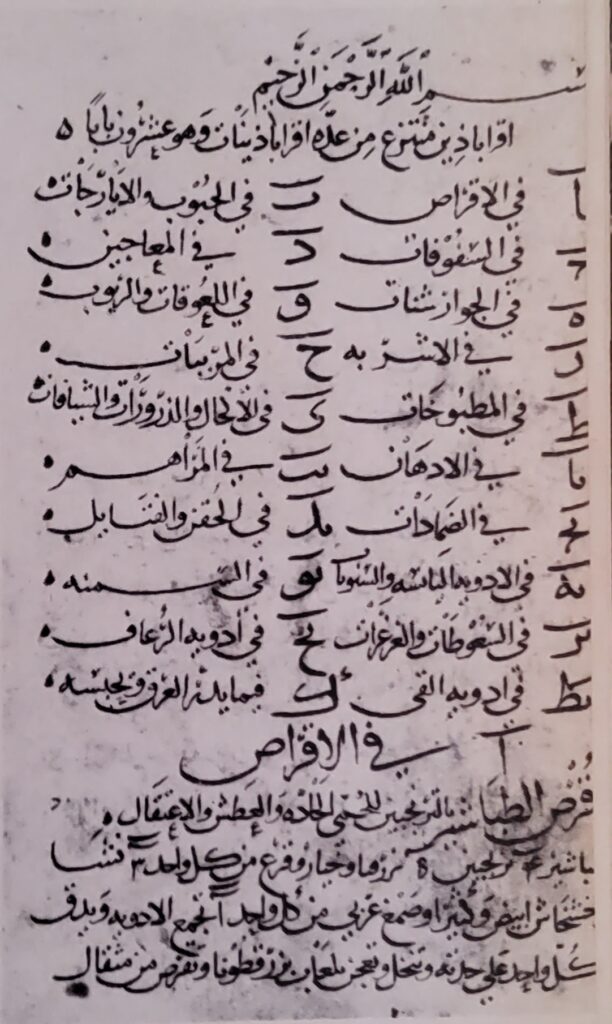

His son Al-Hakam II, was still more ardent in collecting manuscripts and attracting scholars to his court. His library was reputed to contain some 400,000 books and manuscripts, an incredible treasure, when one realizes that a few hundred volumes would then suffice to win fame for a Christian monastery as a great centre of learning. Al-Hakam’s patronage set the example for the nobles and merchants of Cordova, who vied with one another in building collections of their own. There was soon a flourishing book market, where rare and beautifully bound works fetched high prices. One Moslem bibliophile, has left an amusing account of his pique on bidding in vain for a choice volume; the book was bought by a rich merchant who wanted it simply as an ornament to fill a gap on his shelves. A host of scribes laboured to satisfy the literary appetite of the Cordovans and are said to have produced between them some 70,000 copies of manuscripts every year.

So great was the power and prestige of Cordova, that the rulers of the Christian kingdoms of northern Spain would humbly present themselves at the Caliph’s court to solicit help in settling their political or personal problems. Sancho the Fat, journeyed there to seek aid both in regaining his kingdom and curing his obesity. Both his petitions were crowned with success, the latter under the care of the Caliph’s Jewish physician. Scholars from beyond the frontiers of Spain would come to imbibe knowledge from the learned men of Islam.

The Caliphate breaks up

There were those among the Moslems, as well as among the Christians, who looked with suspicion upon this passion for learning, because it threatened to contaminate the purity of their revealed religion. After the death of al-Hakam in 975, power passed into the hands of a ruler of a very different stamp — Ibn Abi Amir, known to his people as al-Mansur the Victorious and to the Christians as the dreaded Almanzor. Starting as a chamberlain to al-Hakam’s infant son, he rose to become the all-powerful minister and commander-in-chief of a puppet Caliph. Fanatically orthodox in his piety, he led his armies deep into Christian territory, sacking cities as far afield as Barcelona, Leon and Santiago; yet finding time on his campaigns to transcribe a copy of the Koran with his own hand. As an usurper, he courted the support of the influential faqihs (religious mendicants) of the strict Malikite school and it was to win the favour of those intolerant fanatics that he ordered a purge of al-Hakam’s great library.

The works of poetry, history and science, lovingly collected by the Caliph were thrown out and destroyed; Ibn-Sa‘id of Toledo tells us that “some were burned and others cast into the palace wells, covered over with earth and stones”. After the tyrant’s death in 1002, there was further destruction. The great military and political machine of the Caliphate began to break up as Almanzor’s sons and successors battled for power. Within seven years, Cordova was overrun by an army of Berbers and Castilians and its palaces sacked. The remaining treasures of al-Hakam’s library and the many private collections, were destroyed or dispersed. The eclipse of Cordova did not mean the end of Moslem civilization in Spain. Though fragmented into a mosaic of tiny principalities, each with its own “king”, army and court, the Moors attain brittle but dazzling brilliance.

Of the many other scholars born in al-Andalus, or attracted to the cultured courts of its princes, three deserve special mention. All were admirers of Aristotle and sought to reconcile the wisdom of the ancients with the truths of Islam. Ibn-Bajja (Avempace) is remembered chiefly as the author of The Rule of the Solitary, a critique of the materialism and worldliness of contemporary Moslem society. His ideas were further developed by Ibn-Tufayl, author of a remarkable allegorical novel, which became known to the West through translations into Latin and the vernaculars. Its hero — ancestor of Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, Rousseau’s Emile and Kipling’s Mowgli — is an infant castaway suckled by a gazelle. The child grows up to attain, through observation and reasoning, not only an understanding of the material world, but through mystical contemplation, an awareness of the Supreme Being. He eventually meets his Man Friday, in the form of a Moslem hermit, from whom he realizes that the truths he had discovered by the light of reason were one and the same, as those taught by revealed religion.

The same theme, the Harmony of Religion and Philosophy (to quote the title of a modern translation of one of his works), informs the thought of the greatest of the philosophers of Moslem Spain — Ibn-Rushd. Known to the West as Averroes, he was famous during the Middle Ages for his commentaries on Aristotle. Averroes held both philosophy and religion to be true and strove to reconcile the two in his writings, but because Averroes’ works were denounced as impious by the faqihs, they found little echo in the rest of the Moslem world. Nevertheless, they came to be eagerly studied, debated and ultimately condemned in the West as subversive of the Catholic faith, particularly in the great work of St. Thomas Aquinas. Thomas was also influenced by another thinker whose name may be added to those of the Moslem philosophers mentioned above — Maimonides, the Jewish scholar of Cordova who sought to synthesize faith and reason.

Africa to the Rescue

In the tenth century, new currents of spirituality from Egypt, Syria and other parts of the Islamic world brought the first sufis (pantheistic mystics) to Spain. “I follow the religion of love,” wrote al-Arabi, one of the greatest of them. “Whichever way love’s camels take, that is my religion and my faith.” The way of the sufi sometimes proved remarkably close to that of the great Catholic saints such as St. Teresa.

The first Andalusian sufi of whom we hear was Ibn-Masarra, who lived near Cordova under the tolerant reign of the caliphs. His writings have not survived, but he seems to have been influenced by the Greek philosopher Empedocles. He taught doctrines, highly subversive in the eyes of the Maliki jurists, such as free will in place of Koranic predestination and the perfectability of the individual, through ascetic practices. By the end of the twelfth century, sufis were to be found in all partsof Moslem Spain. Al-Arabi has left us descriptions of 105, more than half of whom lived in al-Andalus and were at one time or another Ibn-Masarra’s spiritual masters. He himself died at Damascus after a lifetime spent in study, asceticism, and strange mystical experiences. Of the 400 or so books that his biographers tell us he composed, one has left a strong mark on our own Western culture. It furnished precedents for Dante’s poetic fiction of a journey through the realms of the afterlife, with its geometrical topography, its glimpses of the bliss of the elect and its beatific vision of the divine splendour.

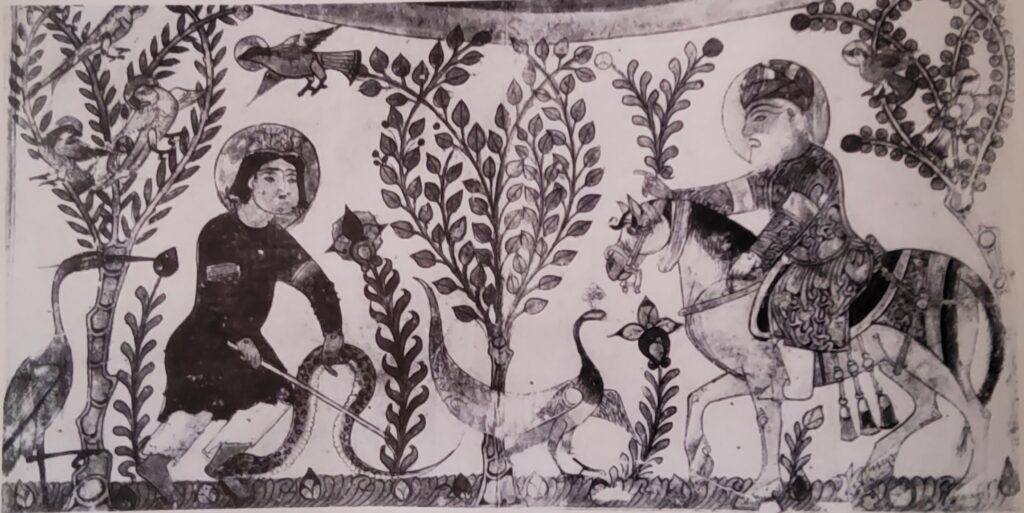

While the sufis were contemplating these mysteries and the Andalusian princelings were indulging their passion for literature, luxurious living and palace intrigue, the warlike Christians from the north were pressing in upon the little Moorish kingdoms. Their tactics were to force an “alliance” on a weaker Moslem prince, extort ever-larger amounts of tribute from him and demand the surrender, first of key fortresses and eventually of the throne itself. The princes, no longer possessing the military strength to resist, turned for help to their co-religionists beyond the Straits of Gibraltar. It was a desperate choice, for Africa was an inexhaustible reservoir of fanaticism; the tribesmen who answered the call — first the Almoravides and then the Almohades or “Unitarians” — looked upon the sophisticated Andalusian Moslems as little better than the Christians.

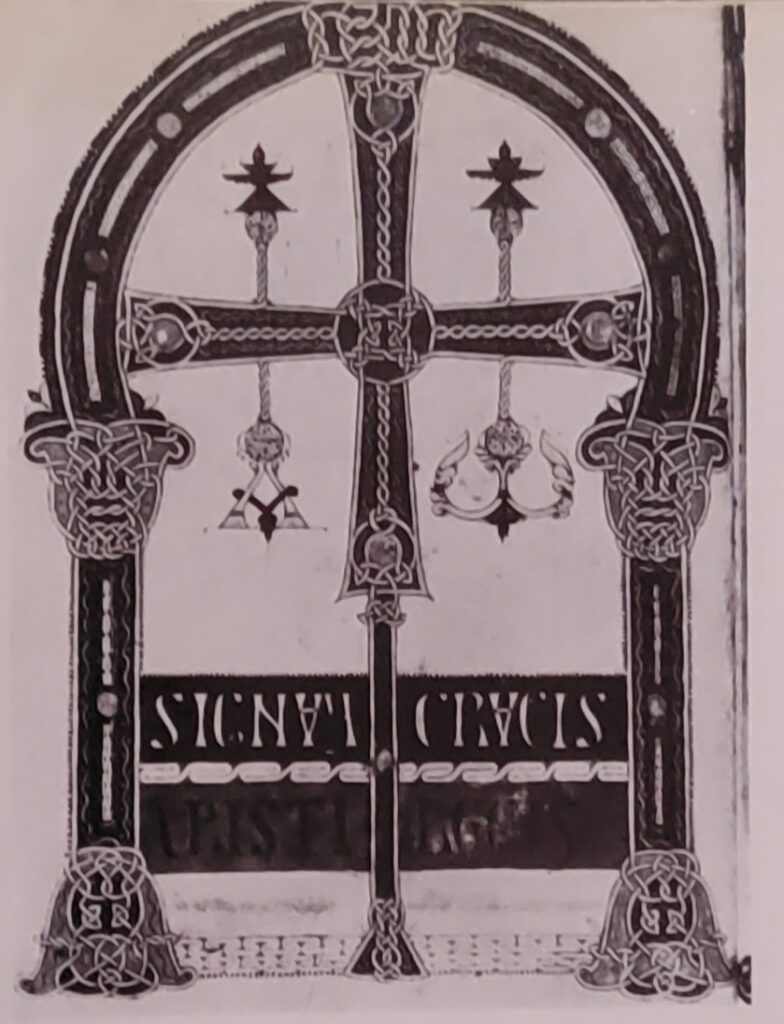

The Christians were repulsed by the Africans and their puppet rulers were ousted, but the invaders themselves came under the civilizing but enervating influence of al-Andalus, until driven out in turn by a fresh wave of fanatics from beyond the Straits. In the process, most of the Mozdrabes, or Christian minorities, who had been tolerated under the Caliphate, but had been increasingly tempted into collusion with the advancing Christians, migrated northwards into Christian territory. So did many Jews, who had likewise lived peacefully with the Moslems but now feared persecution. The population of the expanding Christian kingdoms thus came to include strong elements, both Jewish and Mozarabic, who were familiar with Moslem ways and impregnated with Islamic culture. This they transmitted to the Catholic communities in which they now lived and to the scholars who came from other parts of Christendom, in the quest to learn.

Toledo — Centre of Learning

The natural centre for this work was Toledo, the ancient Visigothic capital situated in the heart of the peninsula and recaptured by the Christians in 1085. Though no Christian kings, until the time of Alfonso the Learned (1221-84), could compare personally with the Moslem princes in intellectual sophistication, they could be tolerant monarchs and enlightened patrons. Alfonso VI, the conqueror of Toledo, prided himself on his title of “Emperor of the Two Religions,” while King Ferdinand III, conqueror of Seville and eventually a canonized saint, added a reverence for Judaism and became “King of the Three Religions.” At least one church in Toledo seems to have been used interchangeably by Jews, Christians and Moslems for the practice of their respective faiths. One Christian churchman, Archbishop Raymond of Toledo, was an admirer of Arabic learning and the chief promoter of what came to be known as the “School of Translators.”

This was not an institutionalized body, such as a university or school, but a tradition of practical scholarship in the translation of Arabic texts on all branches of philosophy and science into Latin and later into Spanish. It lasted for more than a century. Toledo was well chosen for such a task. Many of the surviving manuscripts from al-Hakam’s great library had found their way there and a body of scholars competent to translate them resided in the city. The usual method was for the Arabic text to be translated orally into Spanish by a Moslem, Jewish or Mozarabic scholar and then to be transcribed into Latin by a Spanish cleric.

The fame of Toledo soon attracted scholars from many parts of Europe. Daniel of Morley tells us that he left Paris in disgust at its obsession with law and the pretentious ignorance of its doctors and made his way to Toledo, where true learning was to be found. The Slav scholar, Hermann of Carinthia, made the same pilgrimage in order to study a manuscript of the Almagest by Ptolemy, the second century astronomer whose theory of the movement of the sun and planets held the field in the Middle Ages until discarded in favour of the Copernican system. Hermann stayed on to study and translate many other works by Greek and Arabic scholars, as did Gerard of Cremona, another student of Ptolemy, who is credited with more than seventy translations on geometry, algebra, optics, astronomy and medicine. English scholars showed themselves particularly active in this field. Notable among them was Adelard of Bath, whose quest for knowledge took him as far afield as Africa and Asia Minor. His intellectual curiosity embraced the whole field of human interests from astrology to trigonometry, Platonic philosophy to falconry. Another Englishman, Robert of Chester, collaborated with Hermann of Carinthia and Spanish scholars in translating the Koran, in composing polemical tracts designed to demonstrate the superiority of Christianity to Islam. Michael Scot, who became an astrologer in the Arabicized court of Frederick II of Siciliy, probably acquired his Islamic learning in Toledo. Some Spanish scholars appear to have made the reverse journey to England. Pedro Alonso, a converted Jew from Aragon, played an important part in introducing Arabic astronomy to England and possibly served as physician to King Henry I.

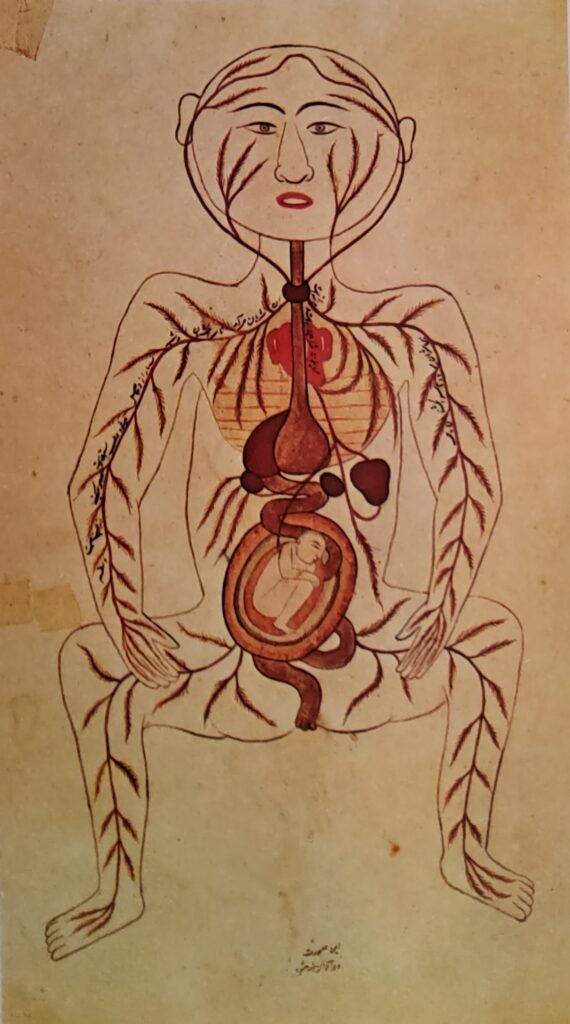

Spain was not the only channel of cultural communication between the Islamic world and Western Europe — Sicily was another intermediary — but it was the most important. Writing in the middle of the twelfth century, John of Salisbury laments the prevailing neglect of mathematics, geometry and logic “except in the land of Spain and the borders of Africa.” In the course of that and the following century, the flow of Greek philosophy and science — the metaphysics and natural science of Aristotle, the medical treatises of Hippocrates and Galen, the works of Ptolemy, Euclid and many other thinkers — enriched by the commentaries and original contributions of the Arabs, began to quicken the intellectual life of a Western European, that had known them only in scraps or not at all.

The Moors had first been lured to Spain by its wealth and fertility; they stayed on to transmit to the West the riches they had inherited from Greece and the East. After nearly seven centuries they were driven from the peninsula. The Spanish Reconquista was a long and complex affair — a tide of Christian conquest ebbing and flowing over the land, but leaving islands where, for considerable periods, Moslems and Christians lived more or less tolerantly together and became influenced by each others cultures. Gradually fanaticism and intolerance were unfortunately to gain the upper hand until under the Catholics, Ferdinand and Isabella, at the end of the fifteenth century, religious conformity became the touchstone of national unity.

Granada, the last outpost of Moslem civilization in Spain, was captured in 1492 and there Cardinal Cisneros presided over bonfires of Islamic texts — as Almanzor had once presided over the purge of the Caliph of Cordova’s great library. However, long before the spirit of tolerance and cultural interchange vanished in the smoke of the Granada holocaust, the scholars of Spain had fulfilled their mission as the industrious middlemen of culture and transmitted to medieval Europe, the forgotten learning of the ancient world.