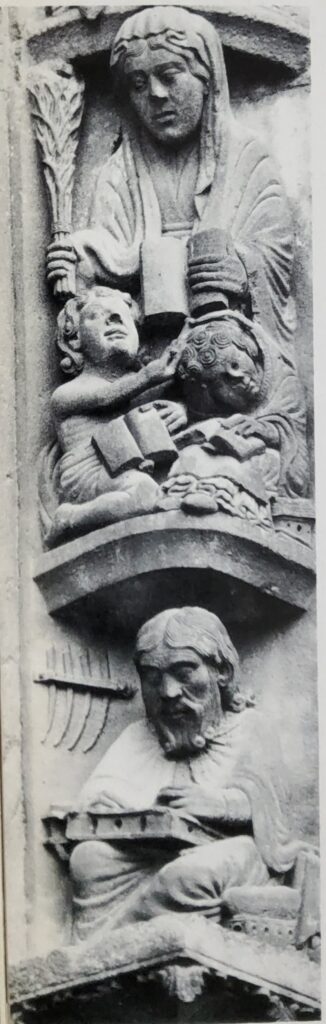

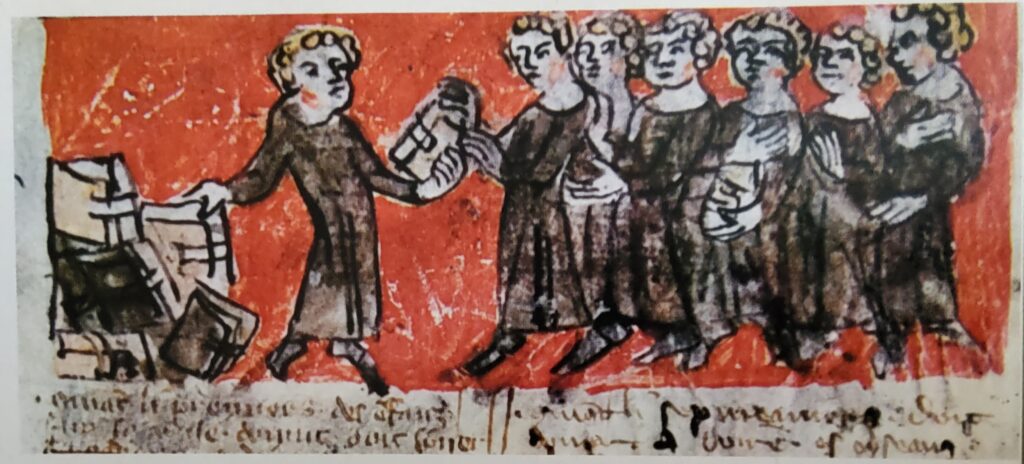

Abelard, Peter – a renowned teacher from Paris, surrounded by a group of questioning students – formed the nucleus of the new universities. Through the early Middle Ages, such teaching and studying, as existed in Europe, was centered on monasteries and cathedral schools – Theology, was the “queen of sciences”. The new universities that sprang up across Europe in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries made it possible for other branches of learning to flourish and develop. The dialectical methods introduced by Abelard were to have a profound influence on the thinking of his day and brought him into conflict with the Church — just as his celebrated romance with the lovely Heloise earned for him the fury and the terrible retribution, of her offended family.

The road from Orleans to Paris was crowded with groups of pilgrims singing psalms, merchants driving pack-animals laden with bundles, horsemen with fine trappings and all sorts. The young student who had been making his way along it for several days saw in the distant hollow of the river, in the glow of the sunset, the bell-towers and roofs of the Ile de la Cité. He urged on his mount: “Paris at last!”

This emotion that Peter Abelard experienced on arriving in Paris was to appear later in his autobiography. Thanks to this work, which Abelard entitled Letter to A Friend, or the History of My Misfortunes, we are familiarized not only with the quite exceptional restlessness that characterized his life, but also with his course of studies and with the intellectual framework of the times.

The reader might well be surprised at the strength of Abelard’s emotion upon reaching Paris, considering the city’s condition in the year 1100. It was a small town, crammed between the banks of the Ile de la Cité, with houses rising in tiers even on to the bridges — the Petit-Pont on the left bank and the Grand-Pont on the right. It hardly extended any farther than the island; only a few small market towns had grown up in the vicinity of the abbeys of Saint-Germain-des-Prés, Saint-Marcel and Sainte-Geneviève. No one could have suspected that one day Paris would become the capital city. The King resided there only occasionally and the Bishop of Paris, was only one of a number of suffragan bishops under the Archbishop of Sens.

Knowledge like power, had yet to reach any degree of centralization; seats of learning were spread over a wide area like the chateaux of the lords of the manor and like the towns that came into being and took shape at the same period. The monastic schools of Bec or Saint-Benoit-sur-Loire and the episcopal schools of Chartres or Reims, were already much better known than the schools of Paris.

Paris attracted Peter Abelard because of his enthusiasm for the subjects of dialectics. He had learned the elements of it in the various schools he had attended in his native Brittany — where his father was lord of the manor of Pallet, near Nantes — and also at Loches where he profited from the lessons of the celebrated teacher Roscelin. However, Guillaume de Champeau, the authority on dialectics, taught in Paris. Thus Abelard decided — when he was about twenty — to go to Paris to hear Guillaume lecture and through him, to perfect himself in the art.

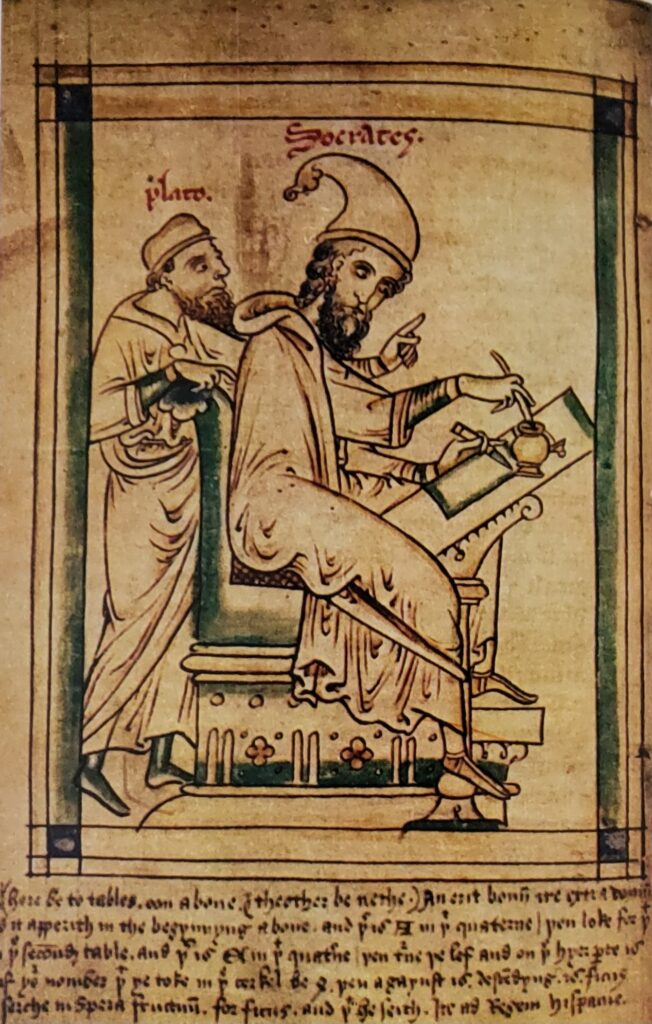

The study of dialectics was pursued with enormous enthusiasm in the student world of the twelfth century and it is important to know why. It is accepted that traditionally the subjects of learning were divided into seven branches, which we know as the seven liberal arts. Whereas the useful arts encompassed the manual crafts — carpentry, metalwork, etc. The liberal arts were concerned both with the physical sphere — arithmetic, geometry, music and astronomy (the quadrivium) and the sphere of the spirit — grammar, rhetoric and dialectics (the trivium). Every student would normally be expected to study these various subjects and to complete the whole cycle. The more gifted ones would then grapple with the “sacred science,” to which Abelard later gave the name of theology.

Grammar was the field we call letters — literature and the study of ancient and modern authors. Rhetoric, the art of expressing oneself, then held a position of great importance, for the whole of medieval culture was based on the spoken word and gesture. These were to be succeeded at the time of the Renaissance by a civilization based on writing and printing. Finally, dialectics was the art of reasoning; it was, as Rabin Maur wrote as early as the ninth century “the discipline of disciplines . . . it is dialectics that teaches us how to teach and teaches us how to learn: in dialectics reason discovers and shows what it is, what it seeks and what it sees.”

Dialectics, then, aroused great enthusiasm in scholastic circles. Its sphere can be compared to that of logic: it showed how to make use of reason in the search for truth, but it also presupposed an exchange of views, a discussion, which was called the “disputation;” logic does not necessarily entail this for it can be carried on by a thinker in the privacy of his own room. The “disputation” took a predominant place among scholastic exercises. At the beginning of each study, there was a reading from a text, the “lectio”. “Reading” was the equivalent of teaching; when later at the University of Paris it was forbidden to “read” Aristotle, this meant that it was forbidden to make use of certain of his works as a basis of instruction.

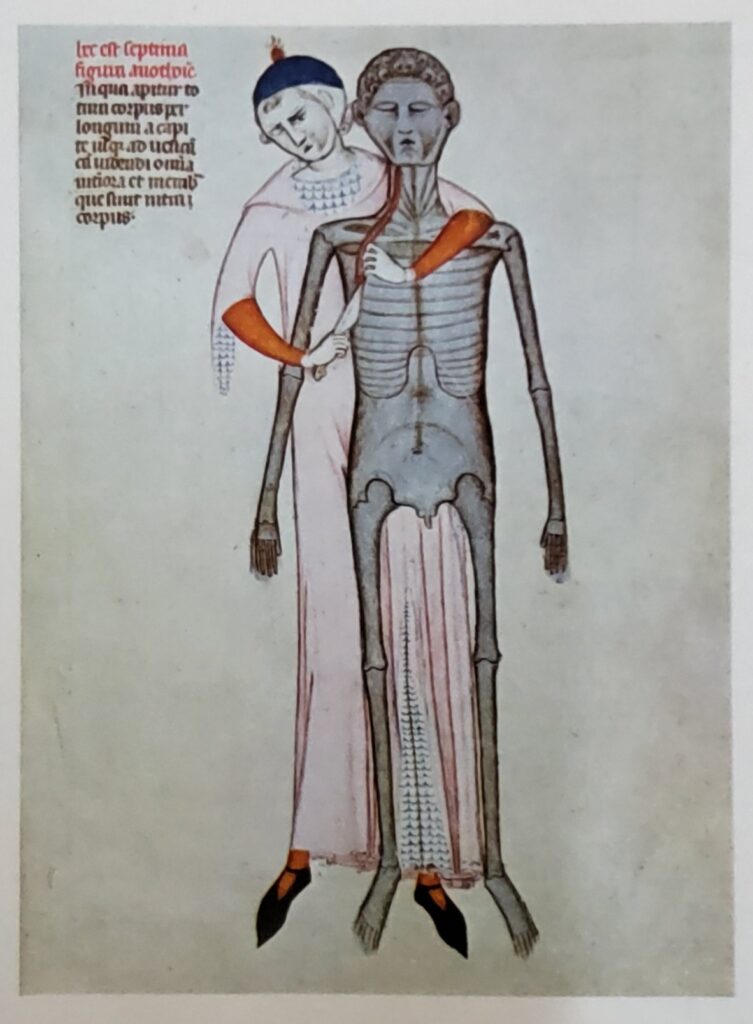

Whenever a teacher embarked upon the study of a work, he first gave a general introduction. He then made a commentary upon it which was called the “exposition” and was divided into three parts: the “letter”, that is to say the grammatical explanation; the “sense”, or comprehension of the text; and finally what is called the “meaning”, that is the deeper meaning or doctrinal content. The “littera”, “sensus” and the “sententia” (meaning) constitute the glossary. There are a great number of manuscripts from this period that reveal this method of teaching, even in their actual layout. Each page comprises one or two central columns of text, while the glossary surrounds the text and fills the top, bottom and sides of the page. A similar layout was to survive in printed books even to the end of the fifteenth century.

When it came to a question of the “sententia” or doctrinal content, a host of questions could be raised, that had to be resolved and it was this, that constituted the disputation or “disputatio” which formed such a distinctive part of scholastic exercises. In the following century, there were a great number of works, in particular several parts of the Summa of St. Thomas Aquinas, which are given the name of Questiones Disputate, that bear witness to the conditions under which they were worked out, i.e. in the course of those disputations in which both teacher and pupils took part. The disputations that are so much in demand by present-day university students were accepted quite naturally in feudal times and survived until modern times.

In fact, they were so readily accepted that an exceptionally gifted pupil like Abelard found it tempting to take advantage of the fact. He had originally been well received by Guillaume de Champeau, that indefatigable disputant, but in spite of his youth he did not hesitate to attack his teacher’s propositions, even to the point of forcing him on two occasions to modify them. This success brought him considerable renown, but it also aroused fierce jealousies, as much on the part of his fellow students as of Guillaume himself. Abelard responded to their attacks by opening a school of his own, first at Melun and then at Corbeil; but he had also set his sights on the chair of dialectics in Paris itself, at the school of Notre-Dame. He succeeded in his ambition and later taught at Mont Sainte-Geneviève, just outside the city. His reputation was a powerful magnet to the students of Paris — among them some from the provinces and some from abroad.

The story of his love for Héloise, the niece of Canon Fulbert of Notre-Dame, is famous, as is the story of Fulbert’s fury when he believed that Abelard was about to desert her. The emasculation that Fulbert’s hired ruffians inflicted on Abelard in 1118 brought to an end, for the time being, his activities as a teacher. He became a monk and retired to the cloisters of Saint-Denis, where he stayed until 1120.

However, the excitement that Abelard had aroused in no way abated. In 1127, the canons of Notre-Dame, finding that the student body had become far too boisterous, decided to expel them from the cloister which they occupied. The teachers and scholars found hospitality on the slopes of Mont Sainte-Genevieve, under the aegis of the abbey of the same name. Abelard himself taught there, at least from 1133 onwards and the Englishman, John of Salisbury, has borne witness to the enthusiasm that he aroused. The originality of his teaching was embodied in his use of the resources of dialectics to prove the truth of certain articles of faith. It was a rash position to adopt; he drew upon Aristotle — as yet little known in the West — when making a commentary on certain fundamental dogmas of Christianity, such as the Trinity. This was to arouse distrust and to scandalize certain defenders of the faith, such as St. Bernard of Clairvaux to such an extent, that Abelard was to find his propositions condemned at the Council of Sens in 1140. He appealed to the Pope, who upheld the Council and Abelard decided to submit to their decision.

The philosopher’s life was to reach a peaceful conclusion in 1142, in the shade of the abbey church of Cluny.

The foundations of the University of Paris

Meanwhile, the “student explosion” had determined the physical layout of Paris. The left bank became the home of the intellectuals and was soon, filled with schools which little by little replaced the vineyards; while the right bank, which afforded easy access for river traffic, became the home of commerce. Paris became honoured as the “fountain of knowledge” and the “paradise of pleasure” for students all over Europe. In the following century, Alexander Neckham was to write, “it is there that the arts flourish, it is there that divine works are the rule.”

Even so, there was still no such institution as a university. When Abelard died in 1142, the methods of teaching had not yet appeared in texts and there was no organization in this effervescent student life. Teachers and pupils found themselves in the houses that from this time on, formed compact rows on the slopes of Mont Sainte-Geneviéve and on the approaches of the Petit-Pont. The Rue du Fouarre, in what is now the Latin Quarter, is a reminder of the bales of straw (feurre, fourre) that normally served as seats and the Rue de la Parcheminerie, recalls the material which was after all the medium for the transmission of thought: the humble lambskin, cleaned and degreased to provide a surface for writing. Each of the folio volumes of those times, so reverently preserved in our libraries today, represents a whole flock of sheep.

In general, the teachers lived in a very hand-to-mouth fashion and the question of their salaries was one that gave rise to fierce debate. Was it permissible to disseminate knowledge for financial reward? Peter Abelard openly declared that his pupils owed him both material rewards and honour, but preachers like St. Bernard of Clairvaux argued violently against those who used teaching for their own profit. No problem existed for those who were assigned a benefice by a cathedral church or abbey and this applied in the case of Abelard, who enjoyed the office of prebendary canon, although this did not mean that he was a priest; nor for those members of the mendicant orders, notably the preaching friars who at the beginning of the thirteenth century had a special duty to teach and were maintained by their orders, despite the opposition of the secular clergy.

Paris attracts the greatest teachers

The bond that linked this sphere of activity to the bishop upon whom in principle it depended was somewhat tenuous. It was the bishop who in the person of his chancellor granted throughout his diocese the licentia docendi, the permission to teach from which arose the term “licenciate” that is still in use. The abbot of Sainte-Geneviève, however, claimed the right to do this throughout the area under the jurisdiction of his abbey.

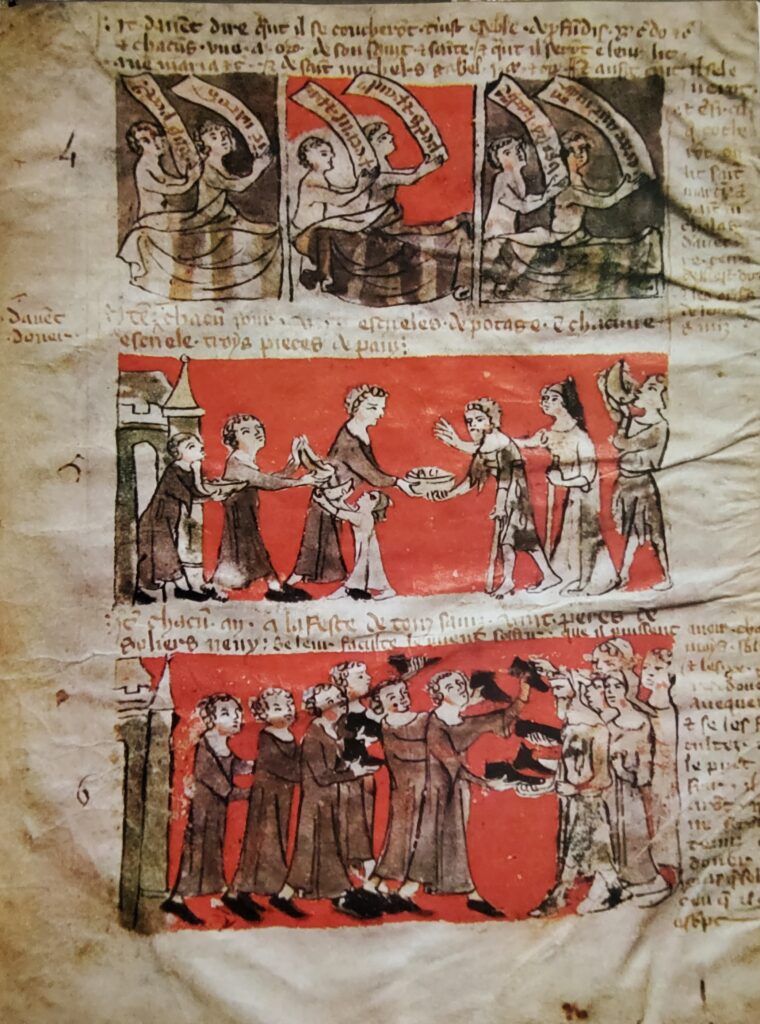

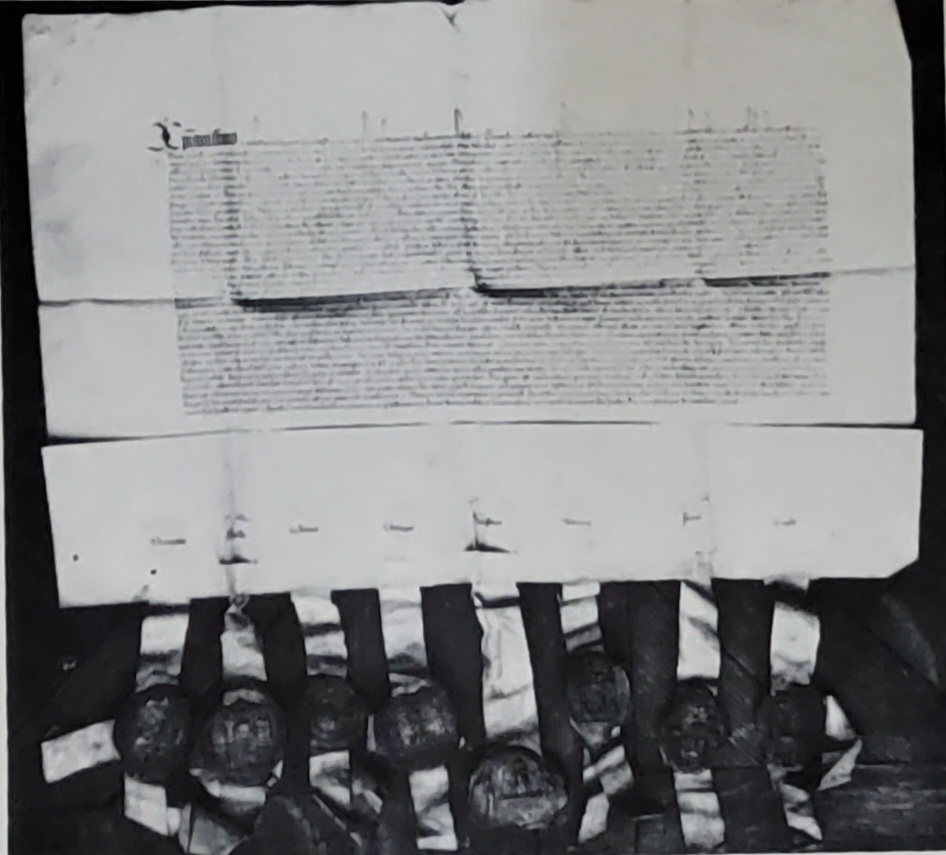

We learn from a bull of Pope Innocent III, dating from the end of 1208 or the beginning of 1209, that a number of disputes arose about the year 1200. Teachers and pupils of Paris then united in a single association and nominated a commission of eight members from among themselves, whose responsibility it was to draw up statutes by which they would be governed. Thus there came into being the Universitas Masgistrorum et Scolarium Paritsiensium, the University; that is to say the association in a united body of the teachers and scholars of Paris. The Pope ratified its autonomy and denied the bishop and his chancellor the right to refuse a licence to whom-so-ever the teachers nominated as qualified to teach. In 1215, the papal legate Robert de Courçon confirmed the rights of the University by approving the statutes that freed both teachers and students from the tutelage of the bishop. At the same period (to be exact the year 1200) the King of France had of his own accord freed the University from the jurisdiction of the royal courts and it was now answerable, only to the ecclesiastical courts. Judicial autonomy was thus added to administrative autonomy; the world of thought and knowledge became the epitome of freedom.

In the thirteenth century, the University of Paris was to earn a great reputation, with teachers like Albert le Grand from Germany, Thomas Aquinas from Italy and Roger Bacon from England, but for all that, its existence was marked by unruliness and agitation. The strike of 1229 to 1231, was triggered-off by a brawl, which had broken out between some students and innkeepers, of the Faubourg Saint-Marcel one Shrove Monday. The royal troops put down the disturbance, rather too rigorously and there was the well-known struggle waged by the secular teachers, against the friars of the mendicant orders, whom they wanted to ban from teaching in their universities.

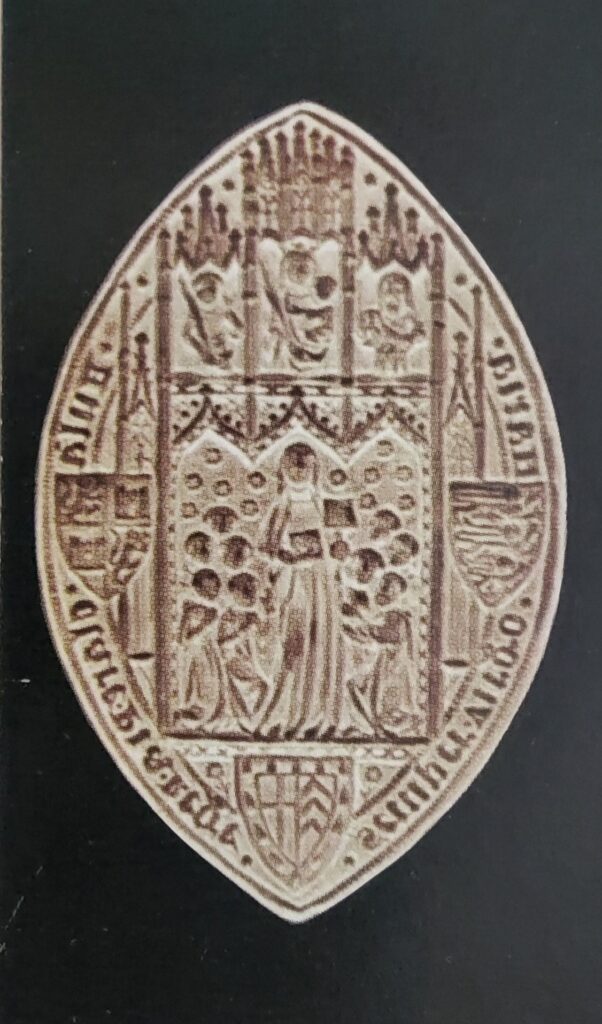

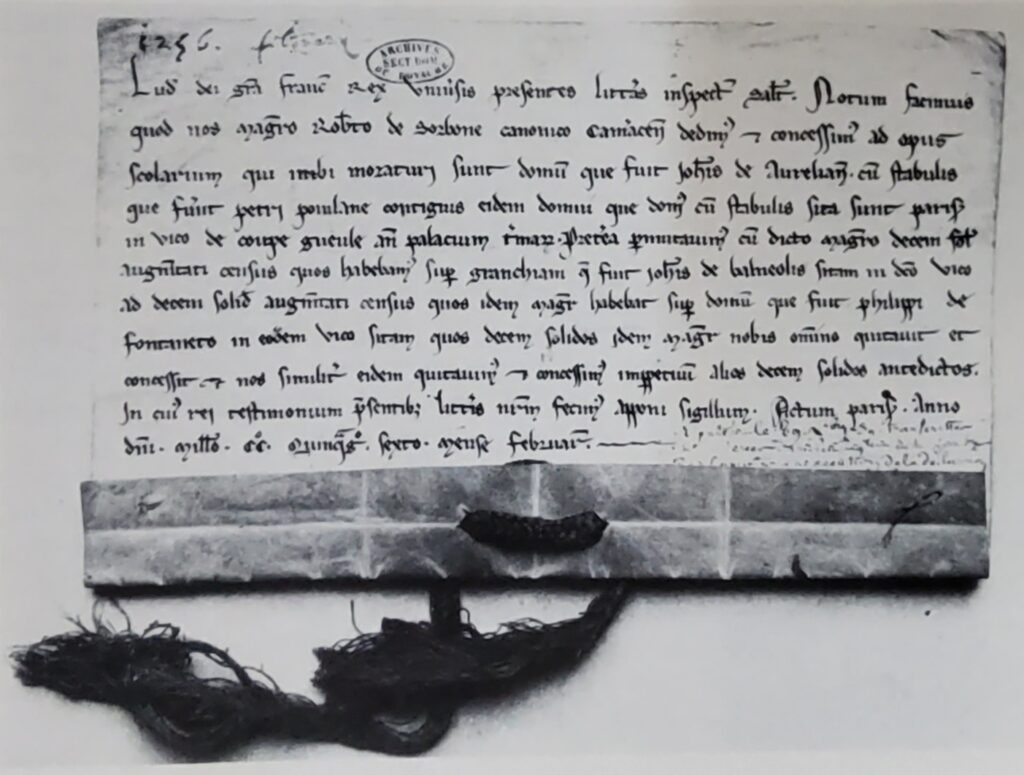

From this time onward, poor students found board and lodging in colleges. The first of these was founded in Paris in 1180 by a middle-class Londoner named Josse. Similar foundations were to spring up: the college of Saint-Thomas du Louvre in 1186 and the college of Bons-Enfants in 1280, but all those were to be eclipsed in the future, by the one established in 1257 by Robert de Sorbon, the chaplain to Louis the Pious.

He founded a college in a house that the King had given him, situated in the Rue Coupe-Guele, which is now the Rue de la Sorbonne. In fact, although the colleges started off as hostels for poor students, they became in time centres of teaching; for example, the College of Robert de Sorbon was the headquarters of the Faculty of Theology of the University.

Although Paris remained famous for its teaching of the liberal arts, as in Abelard’s time, the curriculum was nevertheless distinguished by the inclusion of medicine and theology. From the end of the twelfth century, the students at Paris formed various distinct groups according to their place of origin, in other words, “nations.” There were four nations represented at the University of Paris: French — that is to say, natives of the Ile-de-France — Normans, Picards and English. At the end of the Middle Ages, because of the wars between France and England, the English nation was replaced by the German. Each one had its own statutes. One could discern in these spontaneous groups of students, a foreshadowing of the nations, that were born in the course of the wars of the fifteenth century.

It was in this period, however, that the University of Paris went into a complete decline. The scholastic methods founded upon Aristotelian logic, which had been introduced to the West through the Arab thinkers, particularly Avicenna and Averroes, became set from the beginning of the fourteenth century onwards in formulae which were to ofter an easy butt for the skits of Francois Villon. Under Philippe-le-Bel and then under Philippe de Valois, the University had begun to adopt a political role and its power in the state, seemed to grow in proportion to the decline in the quality of its studies.

It was no longer the only university either; its organization had inspired various other foundations during the thirteenth century. University foundations were to multiply in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, but it was a period of the spread of learning rather than any advance or renewal of intellectual or technical research. The only progress in this period was seen in the science of armament and military equipment, with the introduction of gunpowder.

At this period, the University of Paris was discredited because at the time of the wars between France and England it took sides with the invader. The Sorbonne, the Faculty of Theology, succeeded in maintaining its reputation under the ancien régime, even when the University as a whole went into decline. The brilliance and freshness of Abelard and his enormous influence, had played a decisive part in establishing this reputation. Through his lectures, even more than his writings, Abelard brought reason to the traditional mystery surrounding faith and an independent intellect to the elaborated system of logic. In no small measure, he laid the foundations for the advent of humanism.